Contract testing for Spring Boot APIs sits between unit checks and full end to end environments, with attention on the HTTP surface that clients call every day. Instead of relying only on broad integration scenarios, engineers record expectations about paths, headers, payload structures, and status codes in a contract file, then feed that file into tooling that generates both provider verification tests and client stubs. Consumer driven tests extend this idea by having each client spell out its own expectations in code or a DSL, so any incompatible change in the provider turns into a failing test well before a release reaches production.

Concepts For API Contract Testing In Spring Boot

From the server side, this style of testing ties controller endpoints to the HTTP messages that clients send and read. Every important interaction between a client and a provider gets written into a machine readable file, and that file travels with the code as it moves from local development runs to continuous integration pipelines. Providers treat those files as obligations, consumers treat them as guarantees, and tools sit between the two sides to verify that expectations and actual behavior still match.

API Contracts As Shared Files

An API contract lays out how a client talks to a service in a way that tools can process. A contract for an HTTP endpoint usually records the method such as GET or POST, the path, required query parameters, headers, the body structure for requests, and the status code and body structure for responses. With a tool such as Spring Cloud Contract, those details sit in small DSL files written in Groovy or YAML under a dedicated directory in the codebase. That directory becomes the inventory of interactions that matter for that service.

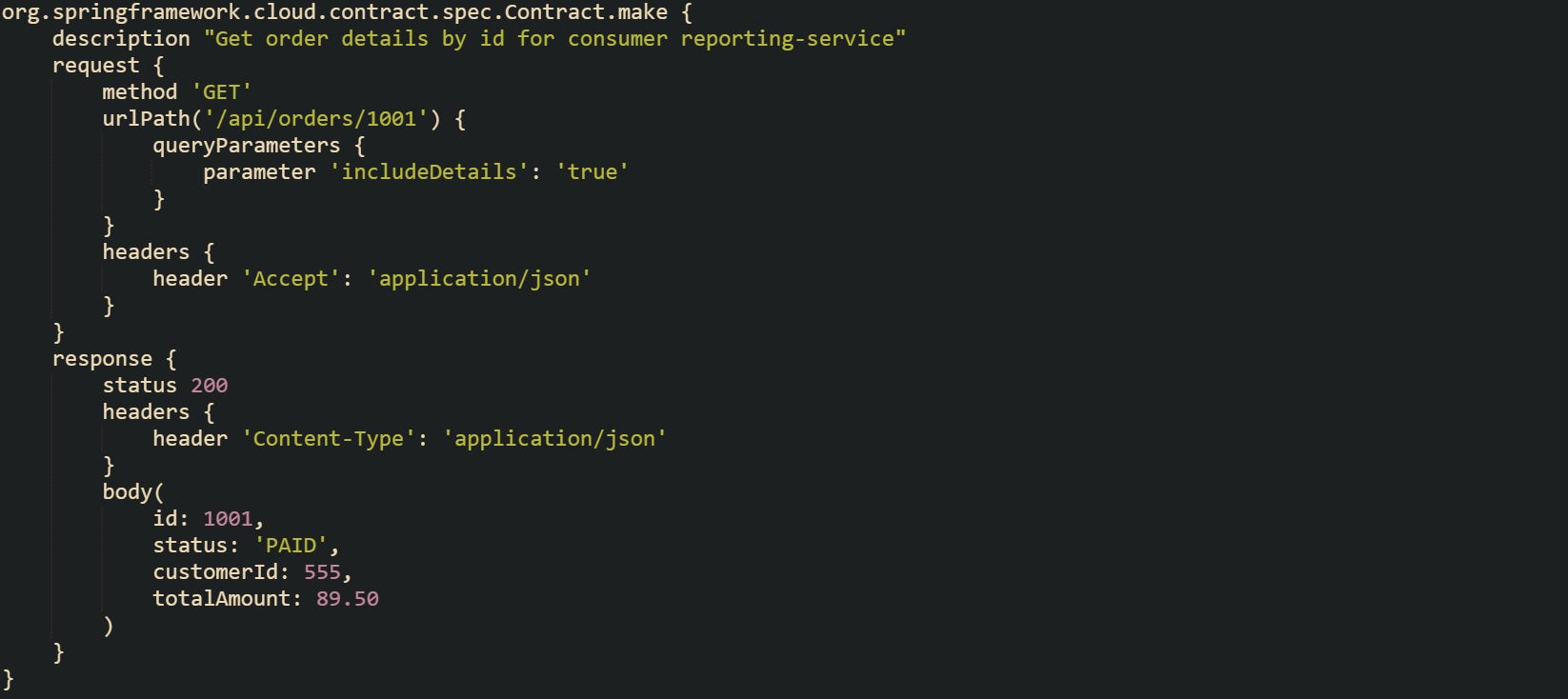

Here is a small Spring Cloud Contract file that can live under src/test/resources/contracts/orders/getById.groovy:

This file tells Spring Cloud Contract that a GET call to /api/orders/1001 with a certain query parameter and header has to return a JSON body with fields such as id, status, customerId, and totalAmount, along with an HTTP status of 200. Nothing in that file knows about controllers or repositories directly, which keeps the contract focused on the HTTP exchange itself.

In many Spring Boot services, contract files live in the same Git repository as the provider code. Some groups keep them in a stand alone repository that both providers and consumers clone, but the idea stays the same. There is a folder full of contracts that act as a shared reference point for both directions of the call. Build plugins read from that folder to generate provider side tests and stub artifacts for consumers. Human readable documentation such as OpenAPI still has a place for broad descriptions of the service, yet contract DSL files are usually more specific and cover concrete request and response pairs, including error cases.

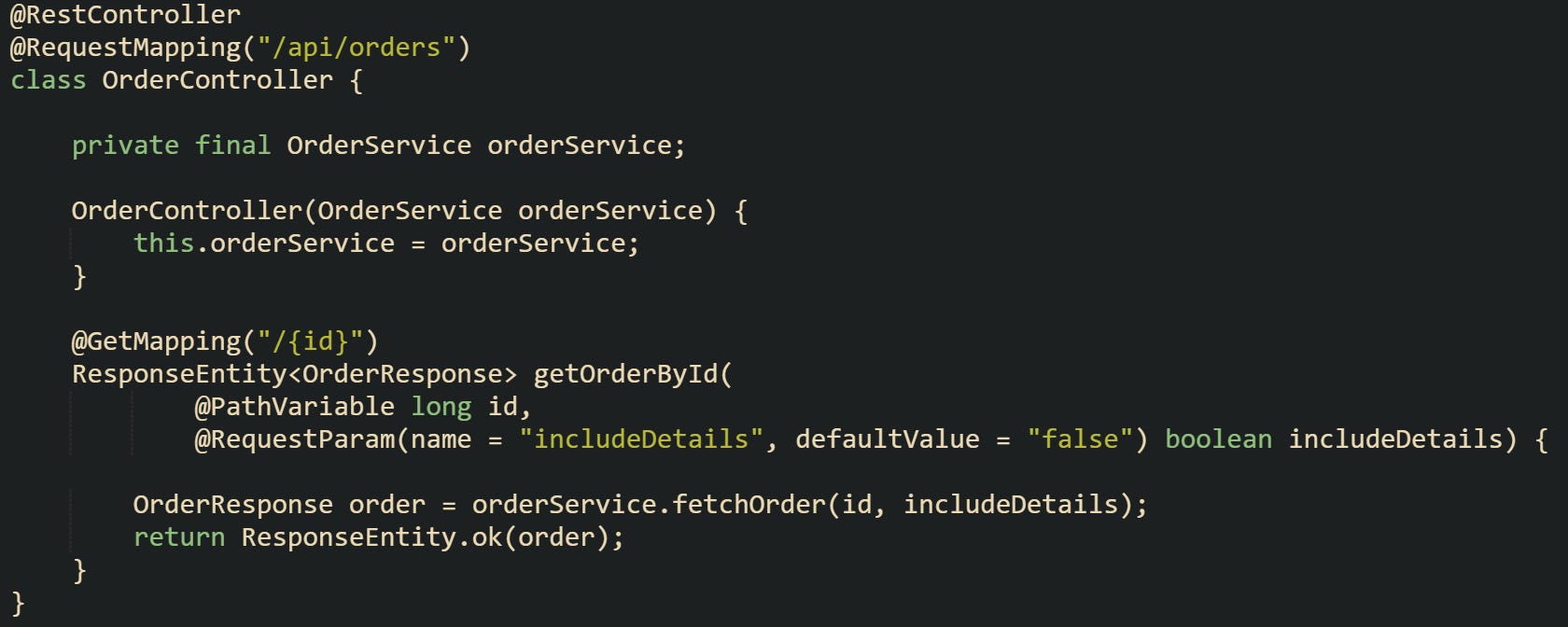

Providers need a way to connect those contract files to real endpoints. One common pattern is to build controllers that match the URLs and payloads written in the contracts and then rely on generated tests to keep them aligned. A trimmed controller that serves the order contract above can look like this:

The controller method getOrderById aligns with the contract by matching the path, query parameter name, and response type, so generated contract tests have a stable target to call. When a developer adds new fields or changes header expectations in the contract files, those tests guide adjustments in controller code and response DTOs.

Consumer Driven Contracts In Practice

Consumer driven contracts change the perspective by starting from the needs of the client. Instead of the provider team writing contracts alone and asking all consumers to keep up, each consumer writes tests or DSL files that express what that one client expects from the provider. Tooling then turns those consumer expectations into contracts that sit in Git and act as the source for provider verification tests and HTTP stubs. Spring Cloud Contract supports this flow by letting consumers author DSL files and contribute them to the provider repository. A consumer can create a contract file locally, run tests against stubs created from that file, and then open a pull request so the provider project can pick up the new contract. The important point is that the consumer has a direct way to record headers, payloads, and status codes that matter for its own integration.

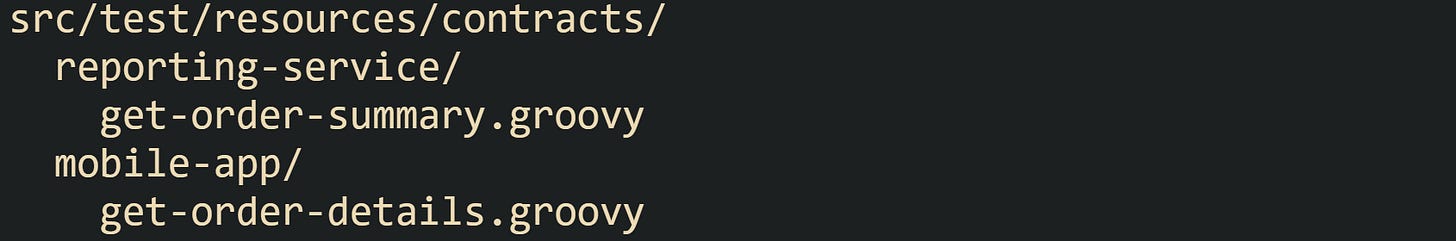

Spring Cloud Contract also has a layout that separates contracts per consumer so that expectations by different clients do not blend into a single flat directory. Provider repositories can use a structure like:

With a structure like this, the provider can see that the reporting-service consumer cares about summary level information, while the mobile-app consumer pulls more detailed information. Generated provider tests can run per contract and the build output can refer to the consumer name when something fails, which helps identify which client depends on which payload fields.

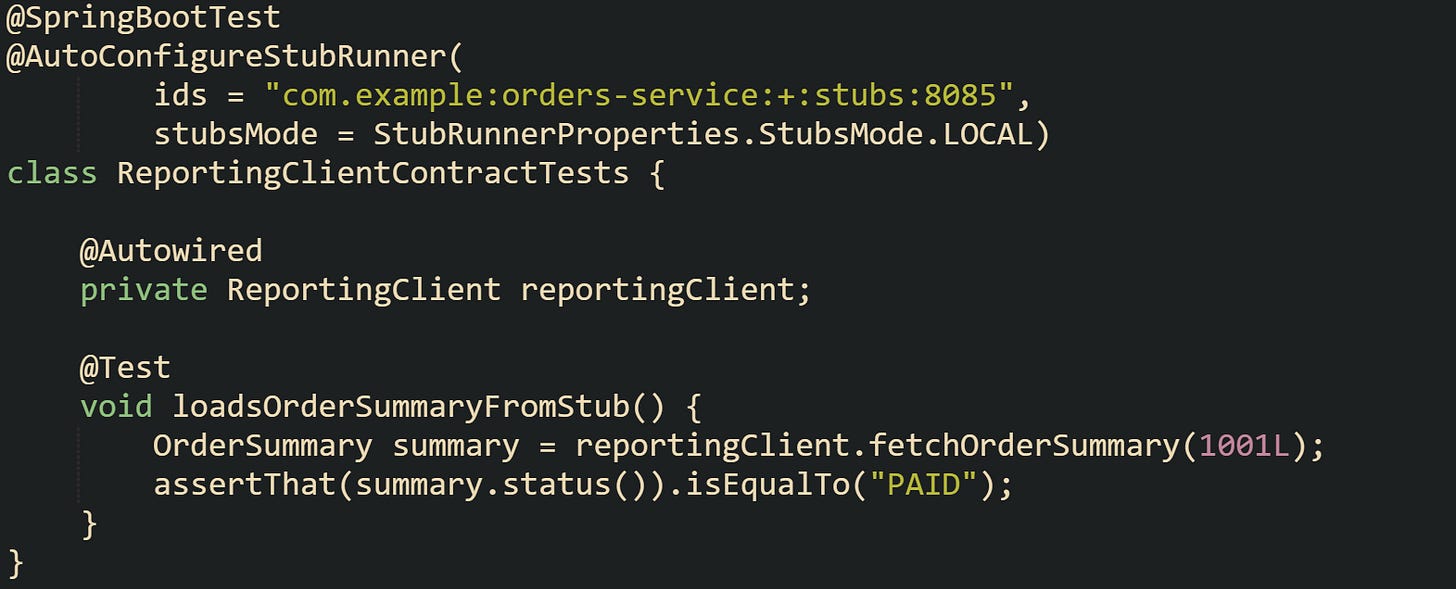

Consumers need a way to test their own HTTP clients against contracts without deploying the provider for every test run. Spring Cloud Contract consumer tests call stub servers backed by WireMock mappings that come from the provider stubs artifact generated from those contracts, so responses match the bodies and status codes recorded in the contract set. Spring Boot consumer tests that talk to a stub server can look like this:

The @AutoConfigureStubRunner annotation starts a stub server that reads contract mappings from the orders-service stub artifact. The ReportingClient class can call http://localhost:8085 during this test and treat it as if it were the real provider. If a change in the contracts modifies the response structure, this test gives fast feedback to the consumer long before any shared environment enters the picture.

With a consumer driven process, contract files and stub artifacts form a loop. Consumers add new expectations and run tests against stubs, providers run verification tests generated from the same contracts, and problems appear as failing tests rather than runtime surprises.

Contract Tests Versus Integration Tests

Contract tests sit in a different place from end to end integration tests. A contract test focuses on how one provider responds to HTTP requests that match the contract files. The provider runs in isolation with its Spring Boot context active and its immediate collaborators either real or mocked. Downstream services outside the boundary of that provider do not need to be up, which keeps the test environment smaller and more focused on the HTTP contract itself.

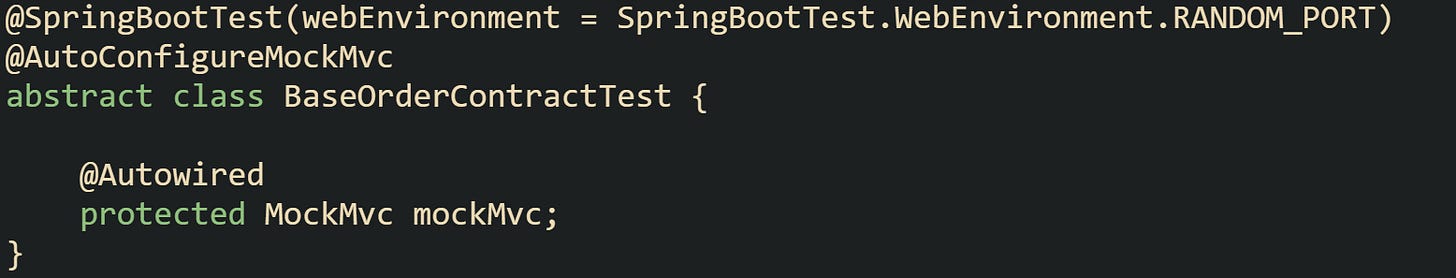

Typical provider side contract test classes in Spring Boot projects extend a base class created for Spring Cloud Contract and then gain generated test methods. One slightly simplified base class can be:

Generated tests extend BaseOrderContractTest and call the real controller layer through MockMvc. A generated method for the order summary contract would build an HTTP request that matches the DSL, call the running provider, and assert on status and body fields. If the controller begins returning a different field set or status code that no longer aligns with the contract, these tests fail quickly.

Integration tests at the end to end level try to run a business flow across multiple services in a shared environment such as a staging cluster. A test for an order flow might start by calling a public gateway, then let that call fan out to order, payment, and inventory services. That style of test gives confidence that configuration, authentication, networking, and service discovery are working, but it also depends on many moving parts outside the scope of a single provider.

Contract tests and integration tests work well side by side. Contract checks run at unit or component scope against local Spring Boot contexts and mock collaborators, giving short feedback cycles tied to one service. End to end tests run at a higher level and at a slower cadence, with fewer scenarios, to watch how multiple contracts behave when chained together. Contract tests protect consumers from unexpected interface changes, while integration tests watch the behavior of the full landscape.

Building Consumer Driven Contract Tests In Spring Boot

Building consumer driven tests takes that foundation and turns it into day to day work in codebases and build pipelines. Consumers write expectations first, contracts move across repositories or brokers, and providers treat those artifacts as input for their own automated checks and stub generation.

Defining Contracts From The Consumer Side

From the consumer view, the main goal is to capture real calls that a client plans to make and keep those calls stable. Spring Cloud Contract does this with Groovy or YAML DSL files, while Pact records live interactions against a mock server and produces JSON documents. Both flows line up with the same story from the previous section, the consumer leads, and the provider proves that its implementation still honors those recorded calls.

Spring Cloud Contract DSL files sit under a contracts directory inside a project. One read operation that fetches a customer profile can start its life in a consumer repository while the client code is still evolving, then move into the provider repository through a pull request after the consumer tests look solid. An example of a contract for that read can look like this:

This contract records a single success scenario for a GET call with a query parameter and a JSON body that has fields a billing client cares about, such as status and creditLimit. The bodyMatchers section keeps the numeric field flexible, so the provider can change the exact number without breaking the contract as long as it still matches the expression.

Consumers do not only care about happy path flows. Validation errors, missing records, and permission problems are just as important for frontends and downstream services, and consumer driven contracts handle those outcomes in exactly the same way. This contract records a not found error for an unknown customer id:

With both success and error contracts in place, the consumer has a reliable way to express how the provider needs to behave across common situations that affect its own logic.

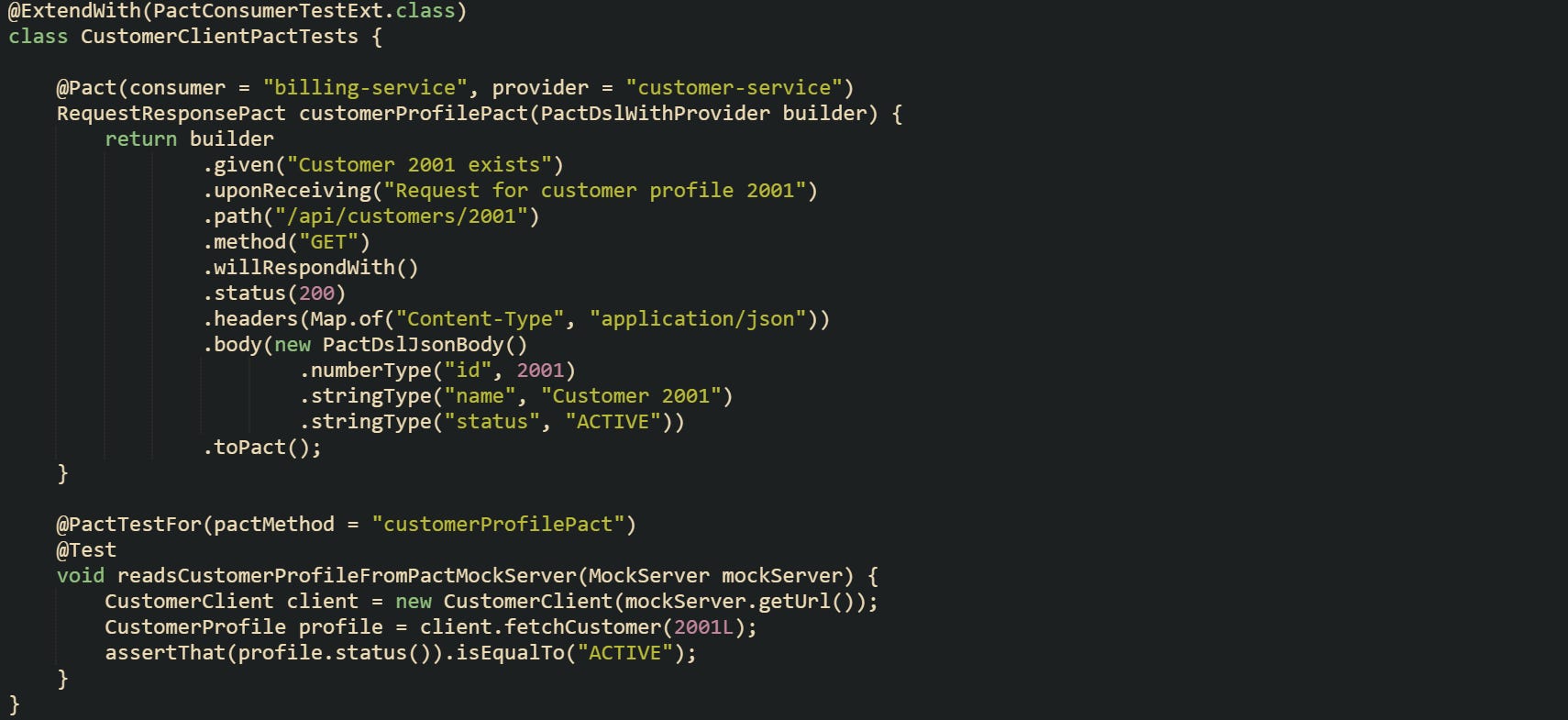

Pact takes a different route to arrive at similar artifacts. Instead of hand written DSL files, Pact consumer tests run against a mock server that records how client code talks to it. After the test, Pact writes JSON contracts that can be pushed to a Pact Broker for providers to read. Spring Boot consumers that use Pact with JUnit 5 can define a contract and test like this:

The method marked with @Pact declares the interaction, and the test method calls a real HTTP client against the Pact mock server. Pact writes a contract file that carries those expectations to the provider side.

In both Spring Cloud Contract and Pact flows, consumers decide which fields matter and which scenarios deserve contracts, then build client tests that exercise those expectations early in their pipeline.

Stub Generation With Provider Verification

After consumers have contracts, providers need repeatable checks that confirm Spring Boot controllers still satisfy those interactions and a way to publish stubs that mirror the current contract set. Spring Cloud Contract concentrates on those needs through build plugins that generate tests and WireMock mappings directly from DSL files.

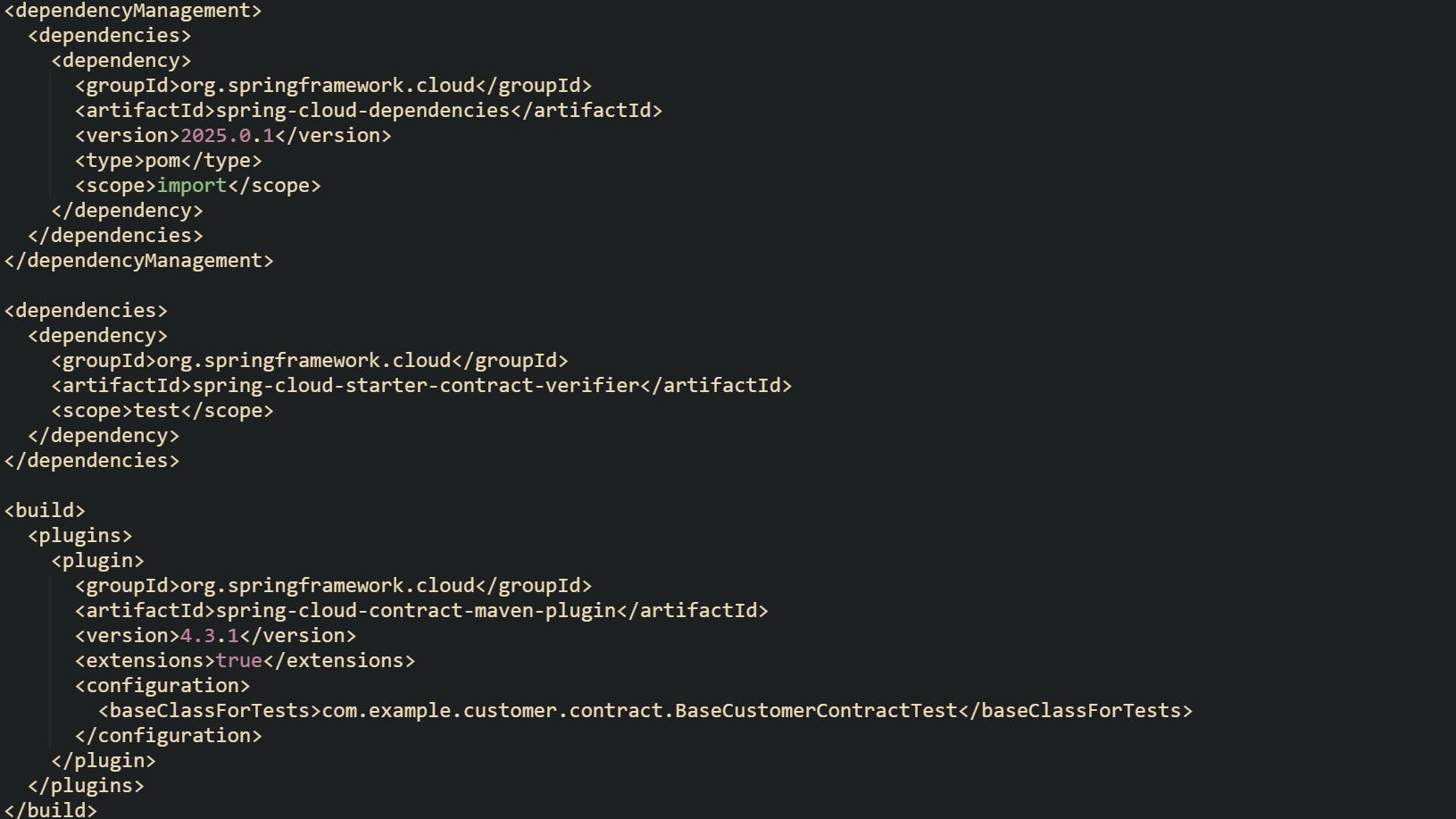

Verification on the provider side starts from contracts stored alongside the provider code, either written by that team or contributed by consumers. Maven builds usually import a Spring Cloud BOM for version alignment and then add the starter and plugin for contract verification. One compact pom.xml extract can be:

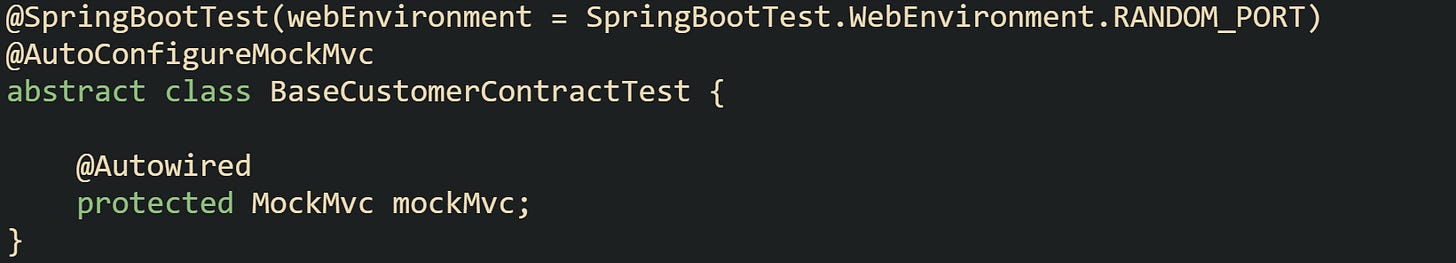

The plugin scans the contracts directory, generates test classes for each interaction, and wires those classes to a base test that starts the Spring Boot context. A base test for a customer provider that uses MVC controllers can look like this:

Generated tests extend BaseCustomerContractTest and perform HTTP calls that match the DSL files. Any mismatch between expected response and actual controller behavior appears as a failing test during the provider build.

Stub generation happens in the same run. The plugin builds a jar that contains WireMock mappings and related metadata derived from the contracts. That stub jar carries coordinates that match the provider artifact with a classifier such as stubs, and it can be published to the same repository that stores other jars. From that point on, consumers can point Stub Runner at the repository and pull stubs that match the contracts the provider just verified.

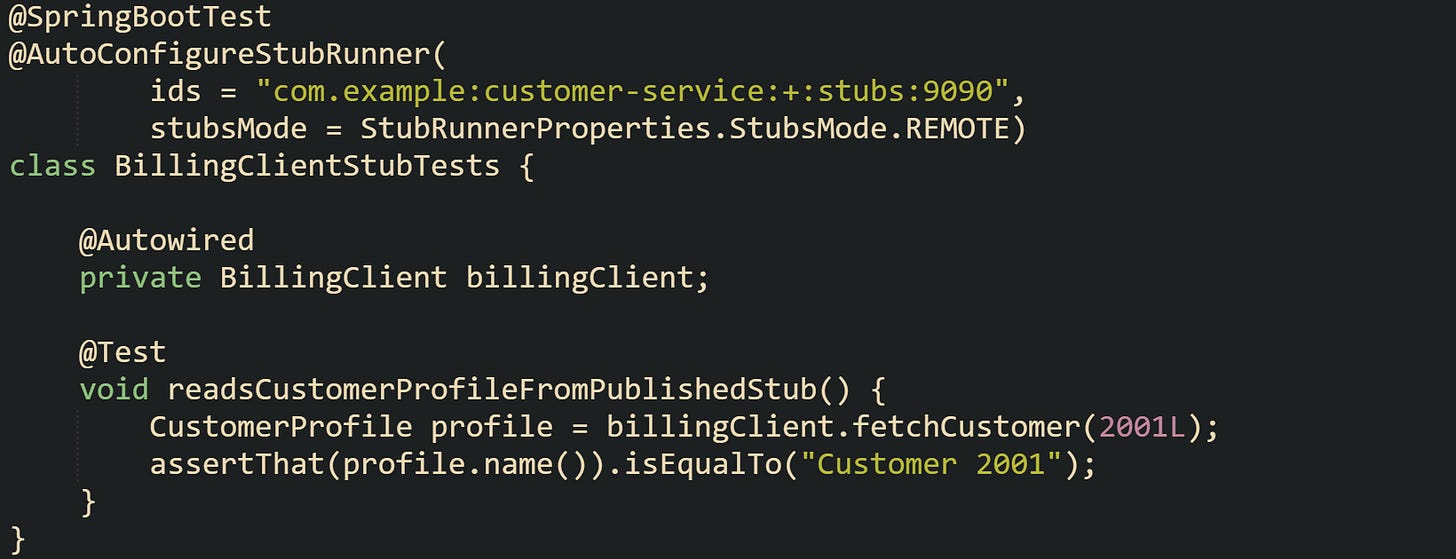

Consumer tests that rely on published stubs follow a pattern similar to the stub usage in the earlier section, but with configuration tuned for remote repositories. Spring Boot billing services that call customer-service can set up tests like this:

The annotation on the test class instructs Stub Runner to download the latest compatible stub jar for customer-service and start a stub server on port 9090. The BillingClient class talks to that port during the test run and sees responses that match the contracts the provider just verified.

Pact providers follow a slightly different route by running Pact verification tests that pull JSON contracts from a Pact Broker and send HTTP calls to live controllers in a Spring Boot test context. The provider then reports verification results back to the broker. That flow still goes well with the core idea shared with Spring Cloud Contract, providers treat consumer supplied contracts as input to automated checks, and only publish artifacts or pass builds when those checks confirm that responses still match the expectations captured on the consumer side.

Conclusion

Contract testing for Spring Boot services turns API behavior into files that tools can read and enforce. Consumers write down the requests and responses they rely on, providers run verification tests from those same contracts, and stub servers replay the agreed interactions for client code. The mechanics stay small and repeatable, from DSL files and Pact JSON through generated JUnit tests and WireMock mappings, so build pipelines can catch breaking changes long before traffic hits production. With that loop in place, Spring Boot APIs evolve while staying aligned with what real clients send and read over HTTP.

![org.springframework.cloud.contract.spec.Contract.make { description "Get customer profile by id for consumer billing-service" request { method 'GET' urlPath('/api/customers/2001') { queryParameters { parameter 'includeContacts': 'true' } } headers { header 'Accept': 'application/json' } } response { status 200 headers { header 'Content-Type': 'application/json' } body( id: 2001, name: 'Customer 2001', status: 'ACTIVE', creditLimit: 5000 ) bodyMatchers { jsonPath('$.creditLimit', byRegex(/[0-9]+/)) } } } org.springframework.cloud.contract.spec.Contract.make { description "Get customer profile by id for consumer billing-service" request { method 'GET' urlPath('/api/customers/2001') { queryParameters { parameter 'includeContacts': 'true' } } headers { header 'Accept': 'application/json' } } response { status 200 headers { header 'Content-Type': 'application/json' } body( id: 2001, name: 'Customer 2001', status: 'ACTIVE', creditLimit: 5000 ) bodyMatchers { jsonPath('$.creditLimit', byRegex(/[0-9]+/)) } } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IvgG!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa93cc0ca-f866-46b3-aebc-2c26f73baf2c_1706x818.png)