Bitwise operators let C code talk directly to individual bits inside integer types and stay part of normal work in C11, C17, and C23. You see them in low level parts of a system, from device drivers to embedded firmware, where a single bit turns a feature on or off or marks a status flag. To work with code in that style, it helps to see how each operator acts on bits, how bit masks group bits into useful layouts, and how short expressions set bits, turn them off, toggle them, or check their state in a predictable way.

Bitwise Building Blocks in C

Working with bitwise operators starts with the idea that integers are collections of bits stored in memory. Each operation in this family reads or changes those bits without caring about decimal digits, and that gives tight control over small numeric pieces inside a wider value. Low level code that talks to hardware registers or packed protocol fields depends on this view of integers.

Binary Representation With Bits

Integer values in C live in memory as sequences of bits. A bit holds either 0 or 1, and each position has a fixed weight in base two arithmetic. For a 32 bit unsigned integer, bit position 0, the least significant bit, contributes 2⁰, bit position 1 contributes 2¹, and this carries on up to bit position 31, which contributes 2³¹. The final numeric value is the sum of those powers of two where the stored bit is 1.

Code rarely refers to bit positions by number in everyday statements, yet every bitwise expression still depends on that layout. When code applies << to a value, bits move toward higher positions and the weight of the value changes. When a mask is applied with AND, only selected positions matter in the result. Keeping that mental framework in the background helps when reading compact flag expressions in real projects.

Unsigned integer types work well for this work. They avoid undefined behavior from shifting negative signed values and from left shifting signed values into ranges that cannot be represented, and they also avoid implementation defined behavior from right shifting negative signed values. Types such as unsigned int, uint8_t, uint16_t, and uint32_t from <stdint.h> cover common register sizes and packed fields that turn up in real hardware manuals.

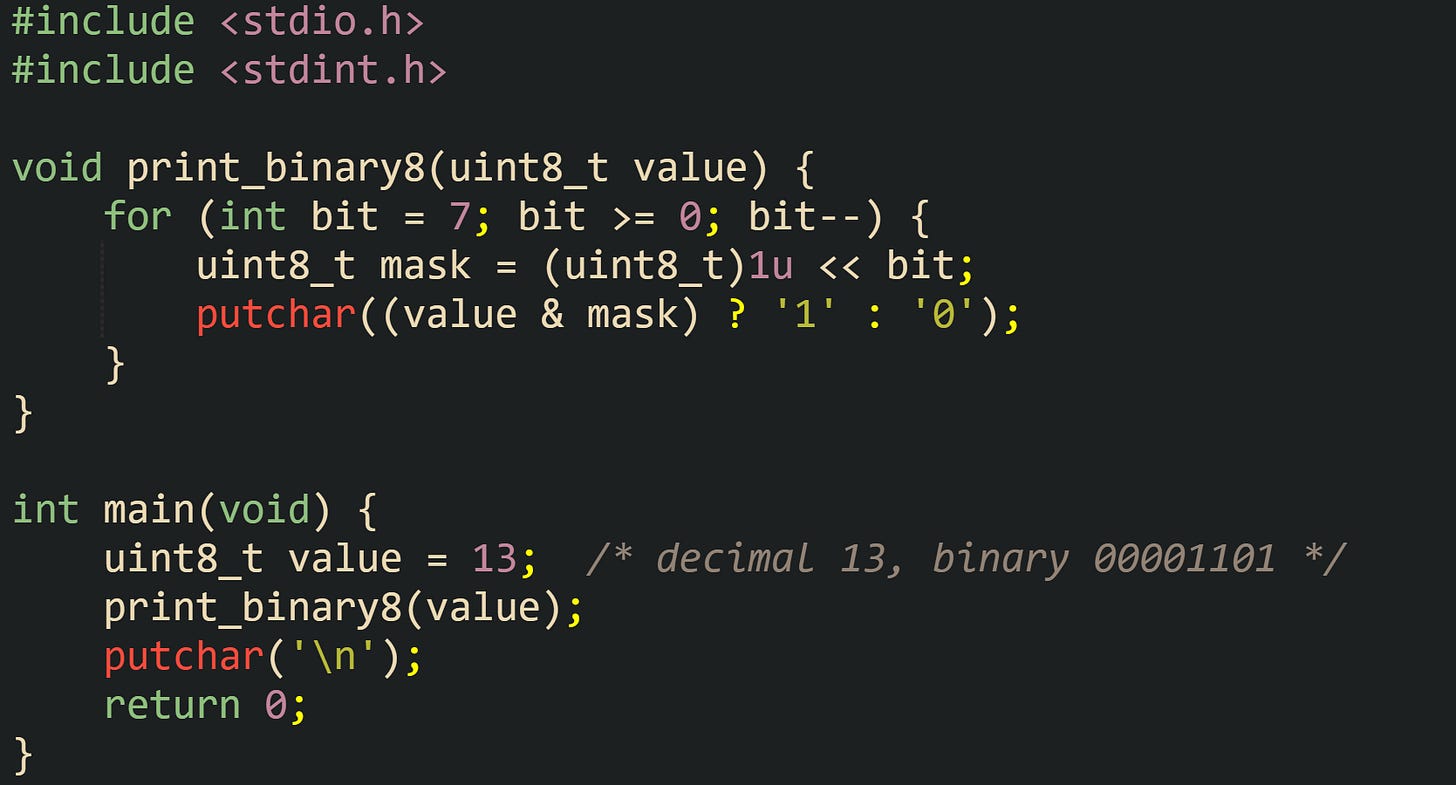

Many projects include a helper that prints a byte or word in binary so developers can see bit layouts directly during debugging.

This helper walks from the most significant bit down to the least significant bit and uses a one bit mask 1u << bit to test each position. The expression value & mask yields zero when that bit is off and nonzero when it is on, and the call to putchar prints either 0 or 1 based on that check.

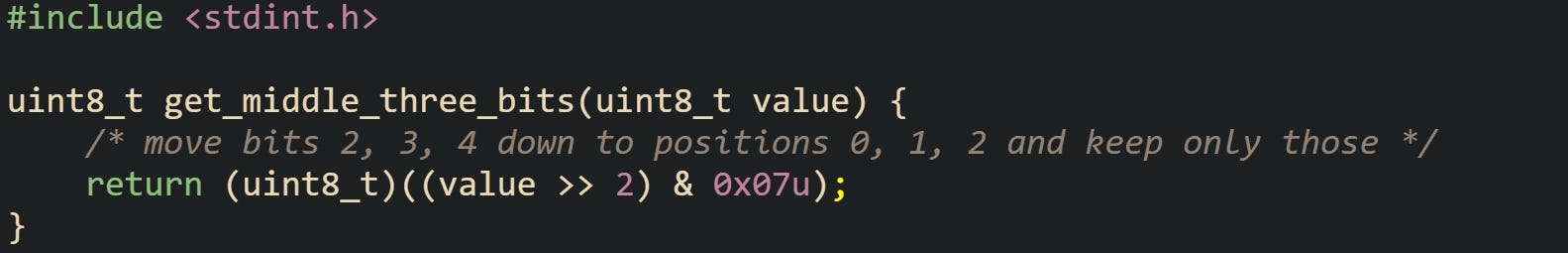

Sometimes code needs to pull out only a few bits from a value. That commonly means moving bits toward lower positions with operator >> followed by a mask that keeps just the region of interest.

For this one, the helper get_middle_three_bits treats bits 2, 3, and 4 of the input as a small three bit field. Right movement brings that field down, and the mask 0x07u keeps only the low three bits, so the caller receives a number between 0 and 7 that reflects just that part of the original value.

Operators That Work Per Bit

C defines six bitwise operators that work on individual bits inside integer operands. The binary operators are &, |, ^, <<, and >>, and the unary operator is ~. Every one of these interacts with the binary representation of the operands rather than their decimal form, and low level code spends a lot of time with them.

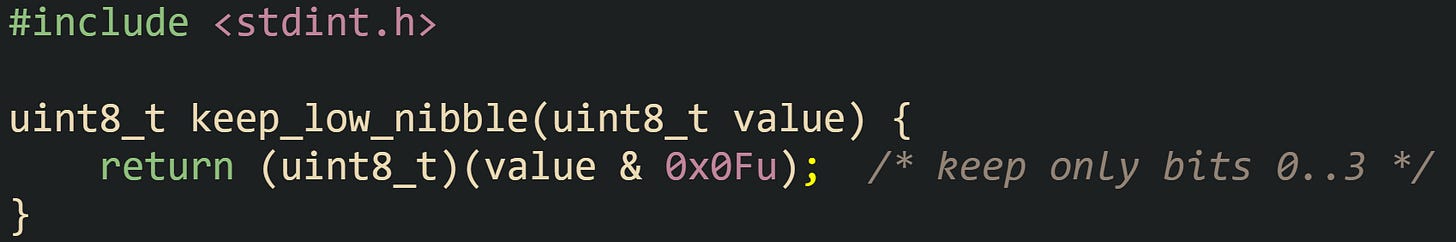

Bitwise AND & keeps a bit only when both input bits are 1. This behavior makes AND a common way to apply a mask and keep selected bits while discarding all others.

The function keep_low_nibble uses the mask 0x0Fu, which has its low four bits set to 1. Any bits in positions 4 through 7 of value become 0 in the result, while the low four bits remain unchanged.

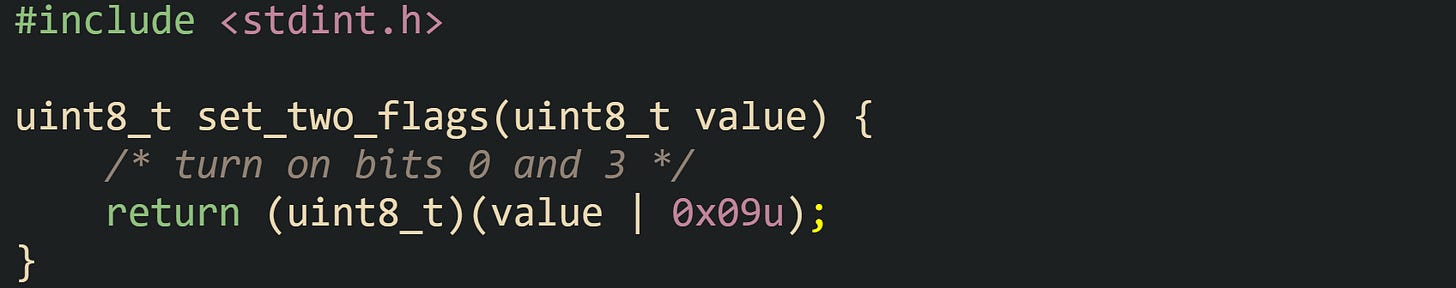

Bitwise OR | sets a bit when either input bit is 1. Code that wants to turn on specific bits without changing others tends to rely on OR.

The return value from set_two_flags always has bits 0 and 3 set to 1, no matter what values were present in those positions in the original byte. Bits outside that mask preserve their previous state.

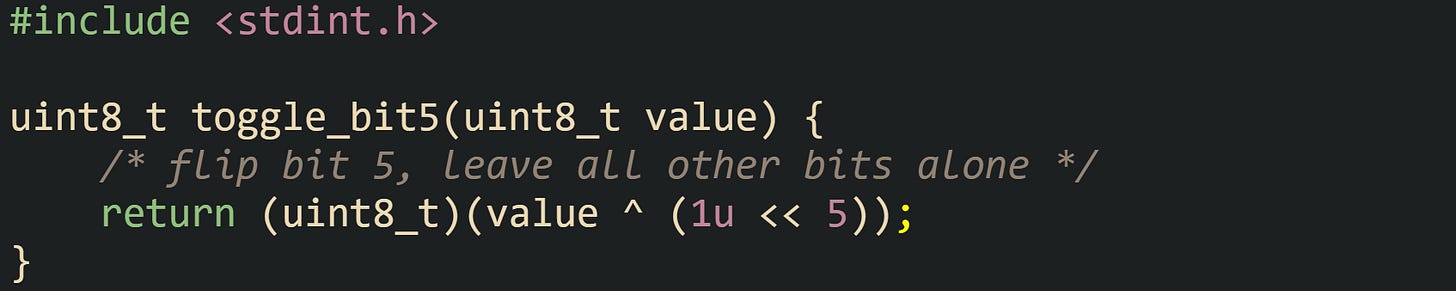

Bitwise XOR ^ produces 1 when the two input bits differ and 0 when they match. This makes XOR useful when the goal is to flip certain bits without touching others.

This helper flips only bit 5 and leaves every other bit in the byte unchanged.

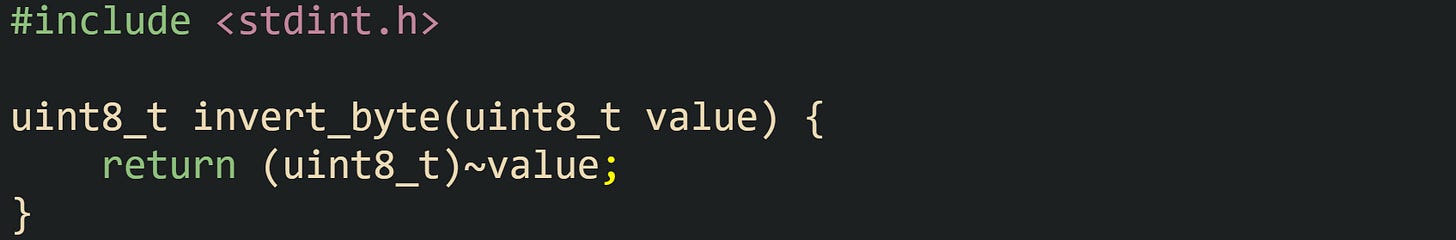

The unary operator ~ inverts every bit in its operand after the usual integer promotions. For small unsigned types like uint8_t, the operation is computed as int or unsigned int, and a cast can then narrow it back to 8 bits.

The function invert_byte returns the bitwise complement of the input, which can be useful with hardware where a flag is active low and stored as 0 for on and 1 for off.

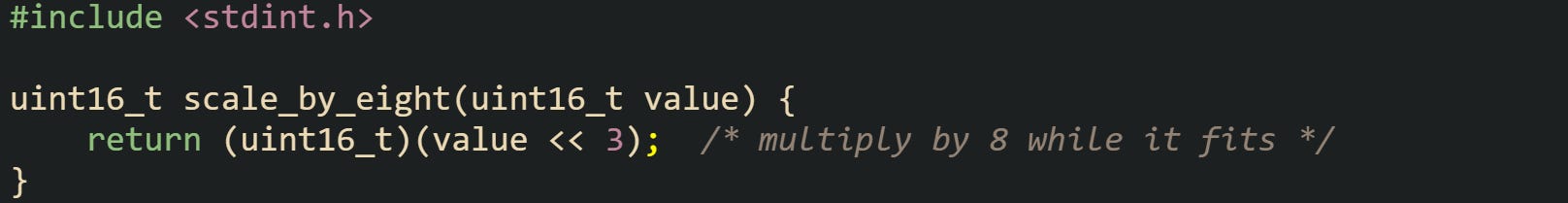

Operator << moves bits toward higher positions within the promoted type. Vacated low positions are filled with zeros. For unsigned types this has the same effect as multiplying by powers of two while bits still fit inside the type.

Generally speaking, care is needed with operator << because the C standard treats a negative count or a count greater than or equal to the width of the promoted type as undefined behavior. For signed types, applying << to a value that does not fit in the result type is also undefined, which is one more reason unsigned arithmetic pairs well with bit manipulation.

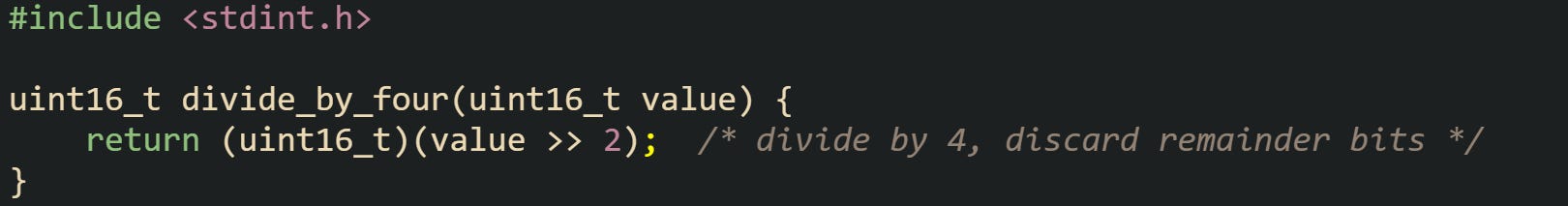

The operator >> moves bits toward lower positions. For unsigned operands, new bits that appear on the left are always zeros, and dividing by powers of two can be expressed as a rightward move when the loss of low bits is acceptable.

Shifts of signed integers need more care as well. Applying >> to a negative signed value is implementation defined. On some platforms the vacated top bits are filled with copies of the sign bit, which keeps negative values negative while changing their magnitude. On other platforms the top bits are filled with zeros. Portable low level code that depends on bit positions usually treats the data as unsigned, performs bitwise operations there, and then casts back to a signed type only when a signed interpretation is needed.

Bit Masks For Low Level Work

Masks turn individual bits or groups of bits into named units that code can work with directly. Instead of remembering that bit 3 controls one behavior and bit 7 controls another, source code can carry readable names that map to one bit or a small cluster. That makes it possible to pack many on or off flags into a single integer, which is common in register definitions and compact data formats that travel across a network or sit in a file.

Flags Stored In Integers

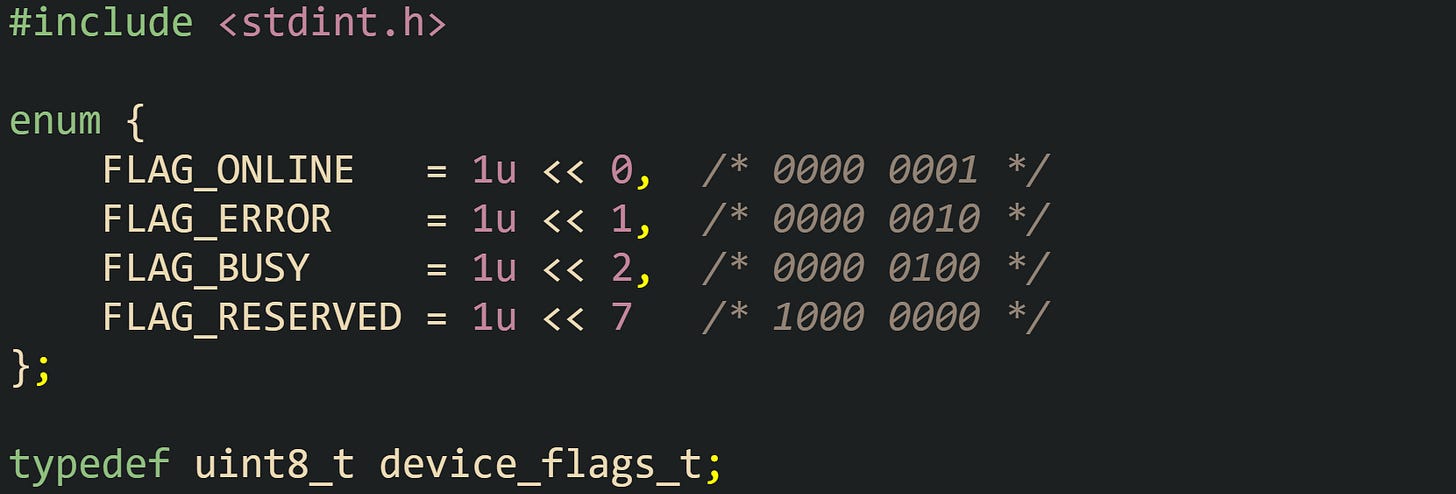

Many low level interfaces expose status or control registers as integers where each bit has a specific meaning. Rather than writing raw numeric constants at call sites, code usually defines masks with a single bit set in each one. An enum works well for this when related flags share the same underlying type.

These constants assign bit 0 to an online flag, bit 1 to an error flag, bit 2 to a busy flag, and bit 7 to a reserved flag. A device_flags_t value can hold any combination of those bits, which means a single byte reflects multiple pieces of state at once.

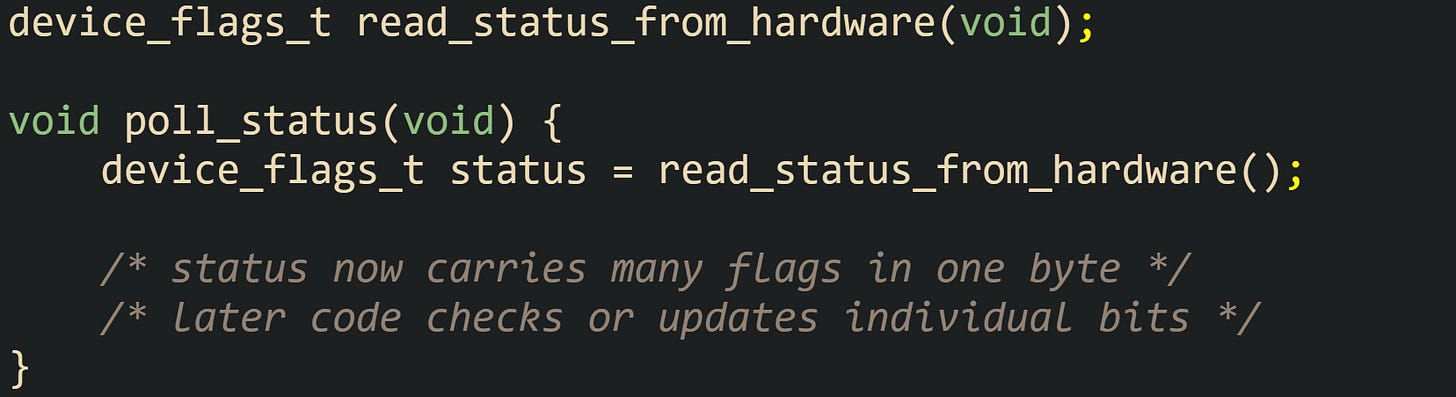

Code that receives status from a device or from a low level library call typically works with a variable of that type like:

The function read_status_from_hardware stands in for whatever platform specific routine fetches the byte from memory mapped I/O or a driver call. The important detail is that status is a compact container for several boolean properties, not a single numeric quantity.

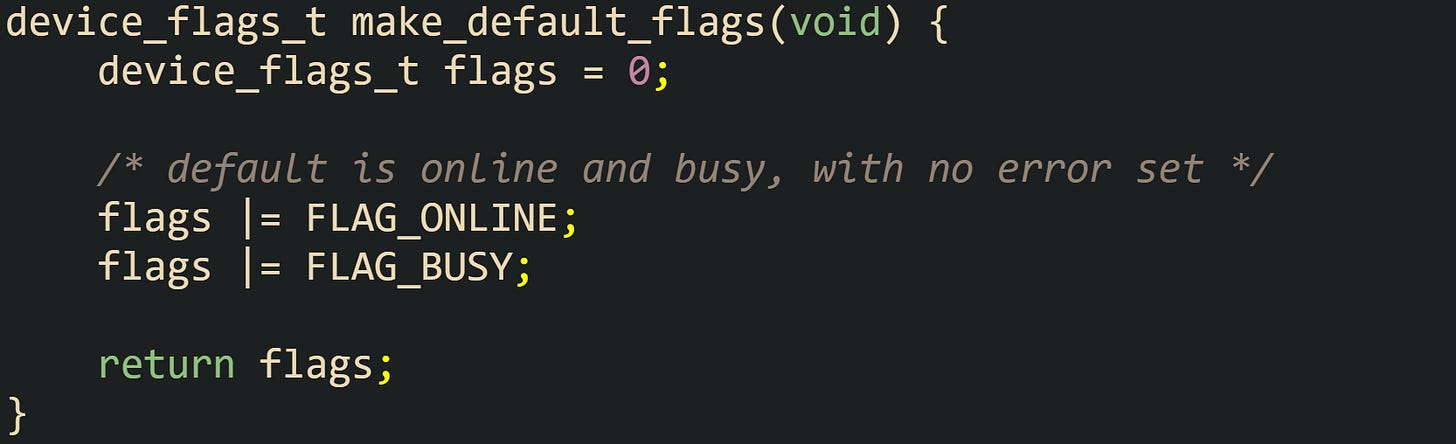

When flags are used for configuration rather than raw hardware state, code can construct them directly by combining masks with OR. That lets one integer variable express a custom blend of features or options.

The function make_default_flags starts from zero, then turns on the online and busy bits. No other bits are disturbed because OR only turns bits on where the mask has a 1 bit.

Set Or Turn Off Single Bits

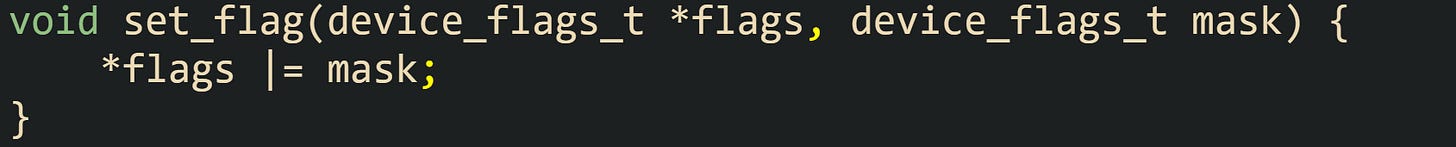

After flags are defined, common work with them boils down to turning specific bits on or off while leaving the rest unchanged. The combination of OR and AND, together with a negated mask, gives short expressions for these updates.

Turning a bit on means applying OR with a mask that has that bit set to 1. The rest of the mask bits are 0 so only that bit changes state.

Here, the pointer flags points to the variable being updated, and the call *flags |= mask guarantees that any bit that was already 1 stays at 1, while any bit that is 1 in mask becomes 1 in *flags. Bits set to 0 in mask place no requirements on the result and stay at whatever value they already held.

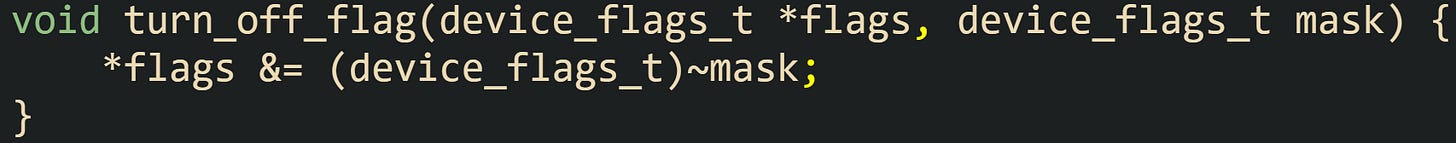

Turning a bit off calls for AND with the complement of the mask. The complement ~mask flips each bit, so any bit that is 1 in the original mask becomes 0 and any bit that is 0 in the original mask becomes 1. AND with that value leaves all bits outside the original mask alone and forces bits inside the mask to 0.

Casting the complement to device_flags_t keeps the width controlled so the result matches the underlying flag type, even though integer promotion rules mean ~mask is computed as an unsigned int value first.

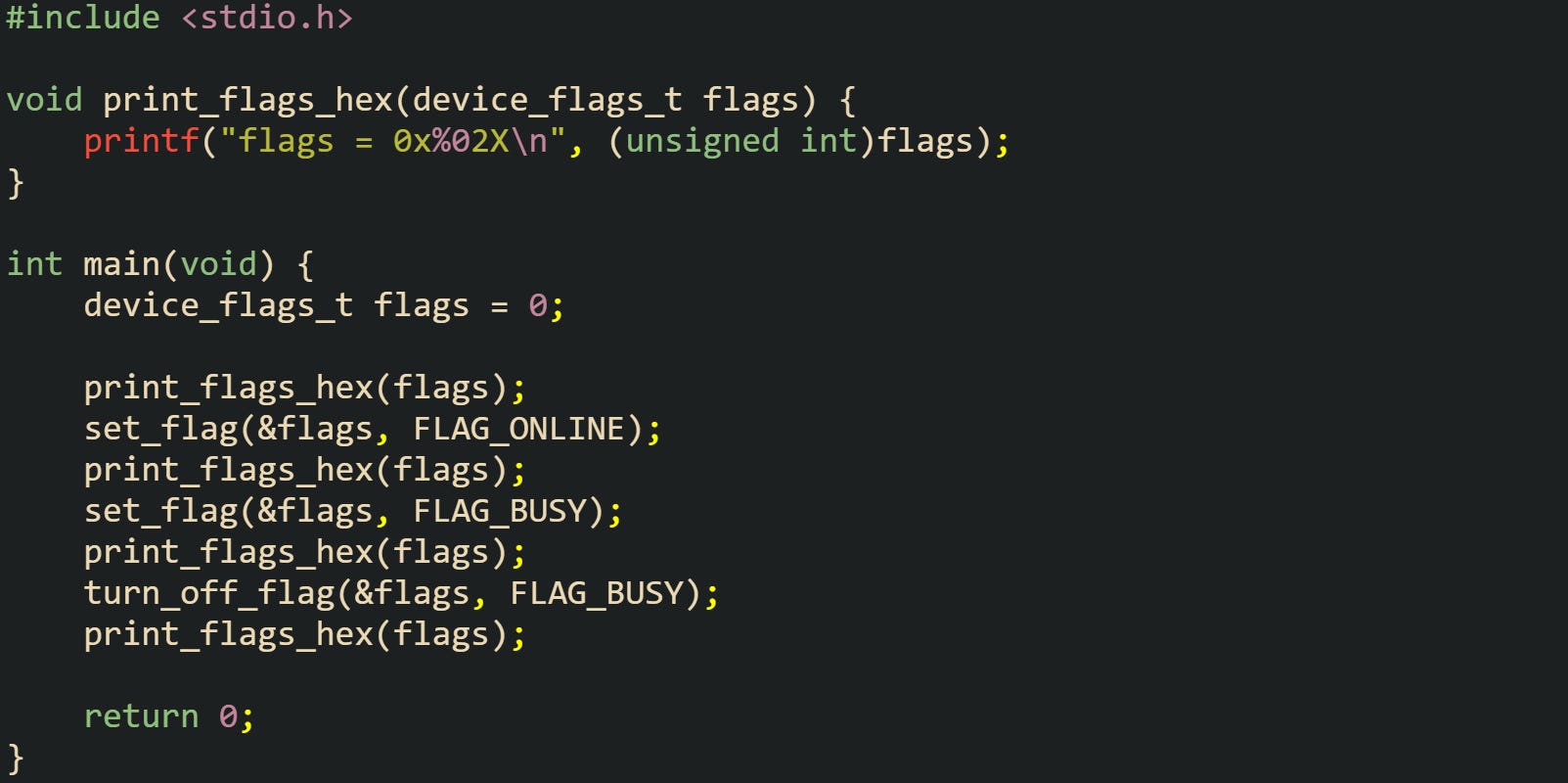

Short helpers that print flag values help during testing and debugging, because seeing the hex representation makes bit state easier to scan, like this:

This walks through a sequence of operations on the flags variable, starting from zero, then turning on the online bit, then turning on the busy bit, and finally turning the busy bit off again. The hex output shows the byte changing at each step, which lines up directly with the underlying bit patterns.

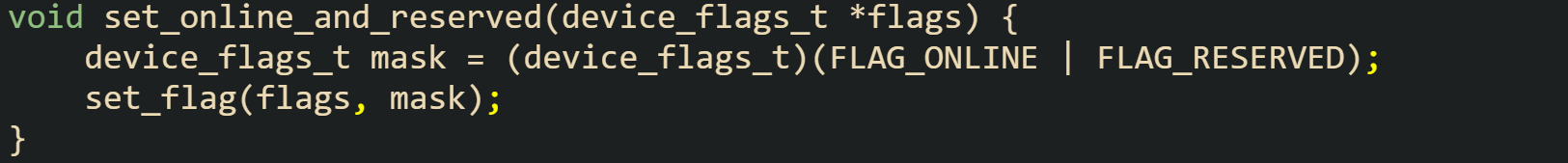

Sometimes code needs to set or turn off several bits in one expression. That works by combining multiple masks with OR first, then passing that combined mask into the helper.

The combined mask has both the online bit and the reserved bit set, so the call to set_flag turns on both bits at once.

Toggle Bits Or Test Bit State

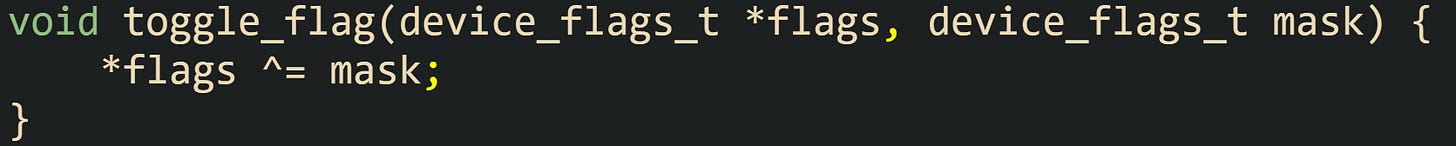

Flag values not only need to be set or turned off, they also need to be flipped and checked. Toggling means changing a bit from 0 to 1 when it was off or from 1 to 0 when it was on. Testing means asking whether a bit or set of bits is present in the current byte or word. XOR has the right behavior for toggling because it produces 1 when the two input bits differ and 0 when they match. XOR with a mask that has a single 1 bit flips that bit and leaves every other position untouched.

Calling toggle_flag(&flags, FLAG_BUSY) on a variable that currently has the busy bit set will turn that bit off while keeping all other bits the same. Calling it again with the same mask turns the busy bit back on. This symmetry makes XOR a natural tool for on or off toggles in user interfaces, state machines, or debug toggles that cycle through branches.

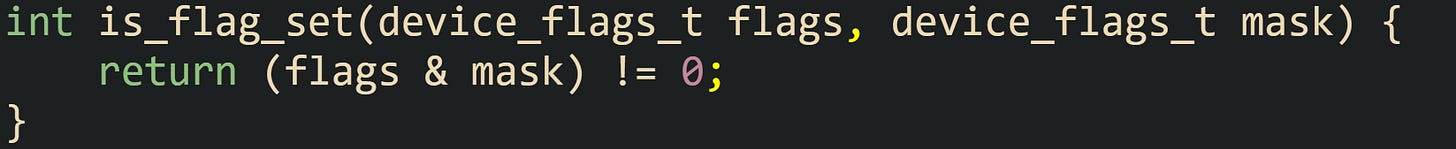

Checking whether a particular flag is set usually means AND with the mask and then comparing the result to zero. If any bit in the mask is present in the value, the AND result is nonzero.

The function is_flag_set returns a nonzero value when at least one of the bits represented by mask is set in flags. For a single bit mask, that means the flag is currently on.

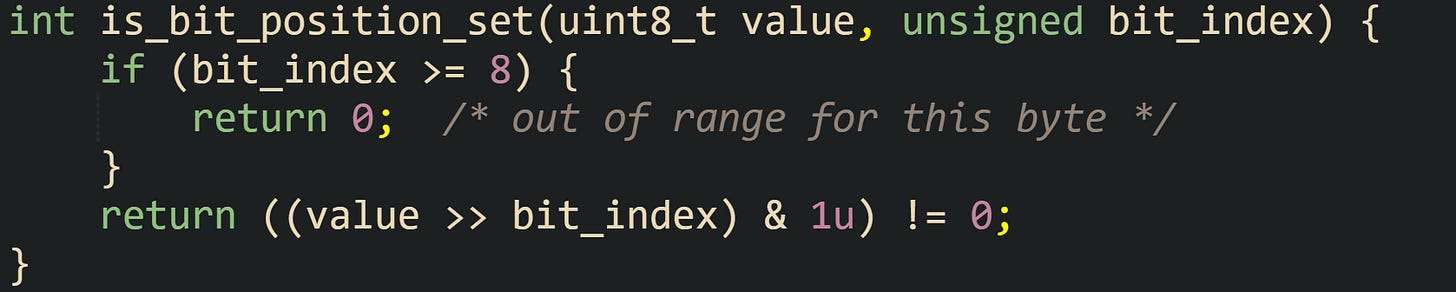

When code needs to check by position instead of by named mask, a short helper that takes a bit index can help. This can be useful in debugging or in generic routines that iterate through bit positions.

This helper is_bit_position_set, moves the requested bit down to position 0 with a right shift and then masks with 1u. The result is either 0 or 1, and the comparison with zero yields an integer result that fits common C idioms for boolean checks.

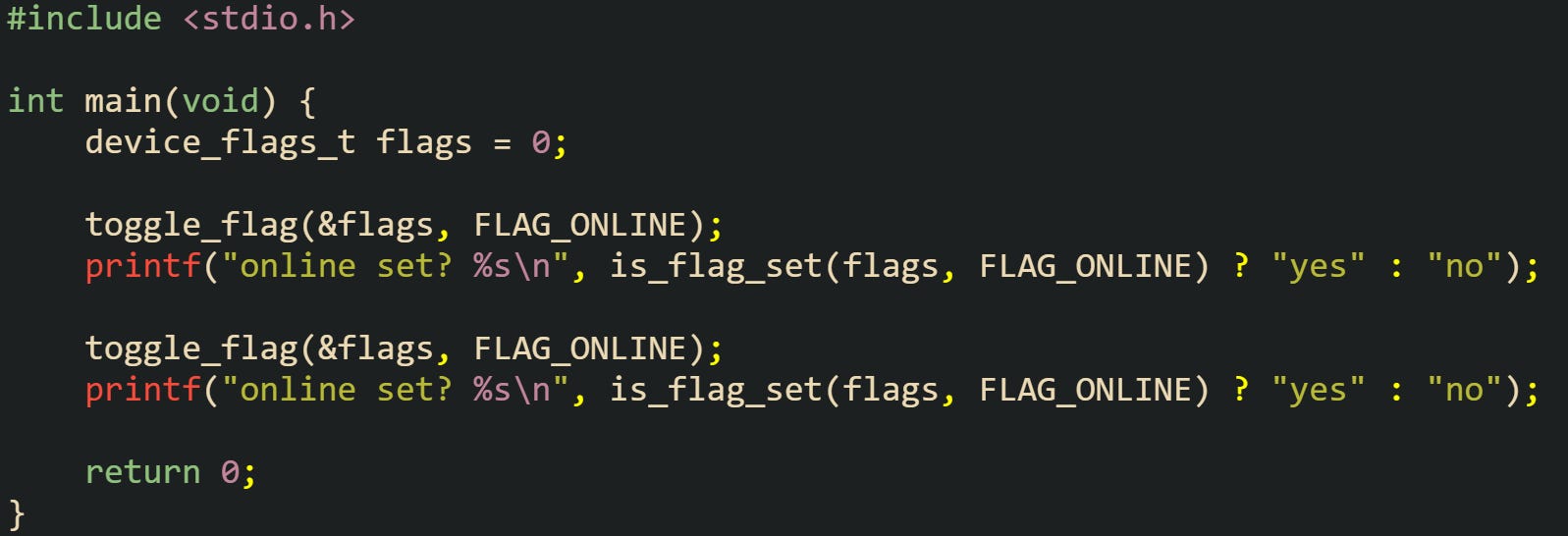

Putting toggling and tests next to each other in a short run can make behavior easier to see:

With this, the first call to toggle_flag turns the online bit on, so the first printed line reports yes. The second call switches that bit back off, so the second line reports no. This outcome follows directly from the rules for XOR and AND, and it matches how flag handling code in systems and embedded work behaves.

Conclusion

Bitwise operators and masks give C code a direct way to control data at the level of individual bits, from how integers sit in memory to how flags live inside packed status bytes. Their behavior follows fixed rules, with &, |, ^, and ~ combining or inverting bits, and << and >> moving bits to higher or lower positions while filling with zeros for unsigned types. Masks assign stable meanings to positions inside an integer so code can set bits, turn bits off, toggle them, and test their state by name rather than by raw numeric constants, matching how hardware registers and low level protocols define control and status fields.

Excellent breakdown of bitwise operators! The emphasis on using unsigned integer types to avoid undefined behavior from shifting negative values is crucial advice for embedded developers. I especially appreciate the practical flag management examples with set_flag, turn_off_flag, and toggle_flag helpers - these patterns come up constantly when working with hardware registers. The print_binary8 utility is also a handy debugging tool I'll be adding to my toolkit.