Modern C compilation takes a plain text .c file and runs it through a chain of tools that turn source code into a native executable the operating system can launch. The preprocessor expands headers and macros into a single translation unit, the compiler turns that translation unit into architecture specific assembly, and the assembler converts that assembly into relocatable object files. A linker like ld, usually driven by gcc, then combines object files and libraries into one binary with all symbol references resolved so that the loader can map it into memory and transfer control to the program entry point.

Source File To Preprocessed Source

Typical C toolchains treat each .c file as a separate translation unit that flows through its own preprocessing stage before any compilation or assembly happens. The preprocessor reads source text, expands headers and macros, applies conditional compilation rules, and produces a single block of C code that the compiler will read next. That structure helps explain why header structure, include order, and macro definitions have such an effect on builds, even when no linking has occurred yet.

C Source Files With Headers

C projects tend to split code into source files with the .c suffix and header files with the .h suffix. Source files usually hold function definitions, global variables, and local implementation details. Header files usually hold declarations that other translation units rely on, such as function prototypes, type definitions, and macros. A compiler only checks calls across translation units correctly when it sees matching declarations, so a header gives that shared view of types and interfaces to all source files that include it.

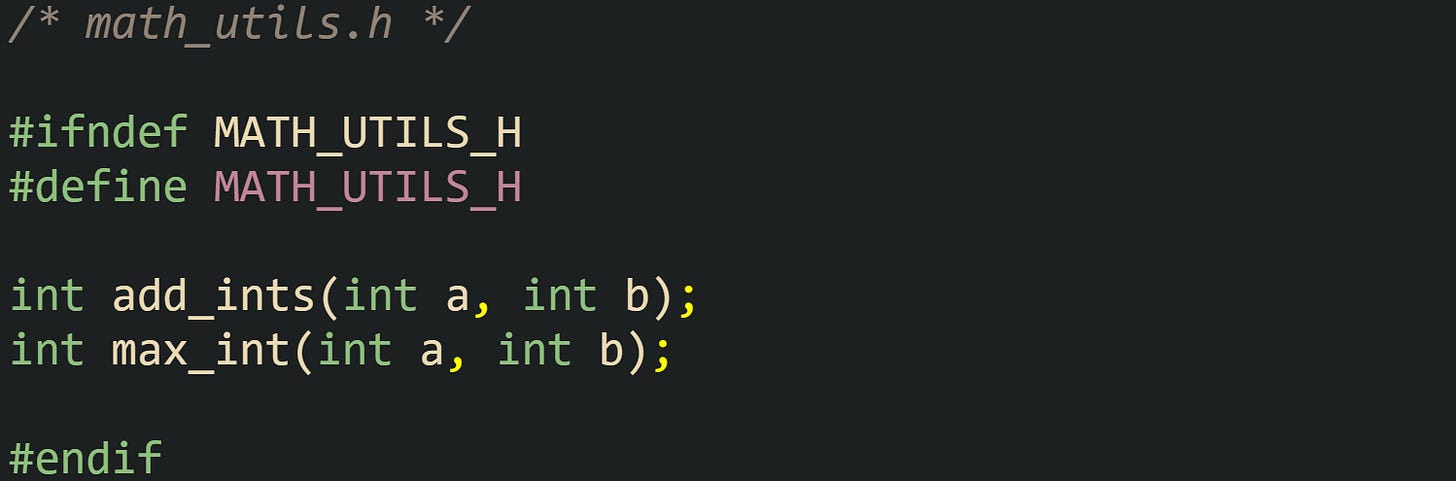

Consider a header named math_utils.h:

And a source file that implements those functions:

Now look at a separate source file that relies on these utilities:

This set of files reflects how a real project grows. Source files refer to each other through declarations that live in headers, while headers give the compiler enough information to type check calls and evaluate expressions in every translation unit. The linker will later tie the add_ints and max_int calls in main.o to the definitions in math_utils.o, but that can succeed only because the header described the functions consistently in all translation units.

Include guards like #ifndef MATH_UTILS_H with matching #define and #endif statements control repeated inclusion of the header in a single translation unit. When several headers include math_utils.h, the guard keeps the preprocessor from inserting the same content multiple times into a translation unit, which helps avoid redefinition or conflicting declaration errors when a header introduces definitions or incompatible declarations. Current compilers also support #pragma once in many environments, but include guards remain portable across C toolchains.

Header layout also shapes how the preprocessor expands translation units. If a header itself includes other headers, the preprocessor will insert that whole chain of text into every source file that requests it. That means a #include tree expands to a large flat block of source where all declarations and macros appear in a single sequence. Careful header structure keeps that combined text readable for humans when reviewing preprocessed output and keeps build times under control by avoiding redundant work.

Details Of Preprocessing Work

The preprocessor runs before the compiler and treats source as text rather than as typed C entities. It replaces #include directives with file contents, expands macros, and decides which conditional blocks stay based on defined macros and expressions in #if and related directives. That processing yields a translation unit where #include and macro expansion have already happened, and preprocessor output commonly includes #line linemarkers so diagnostics still point back to the original files. The compiler then parses that translation unit and generates diagnostics if any syntax or type rules are broken. Errors that stem from macros can appear far from the original macro definition, because by the time the compiler runs, only the expanded text remains.

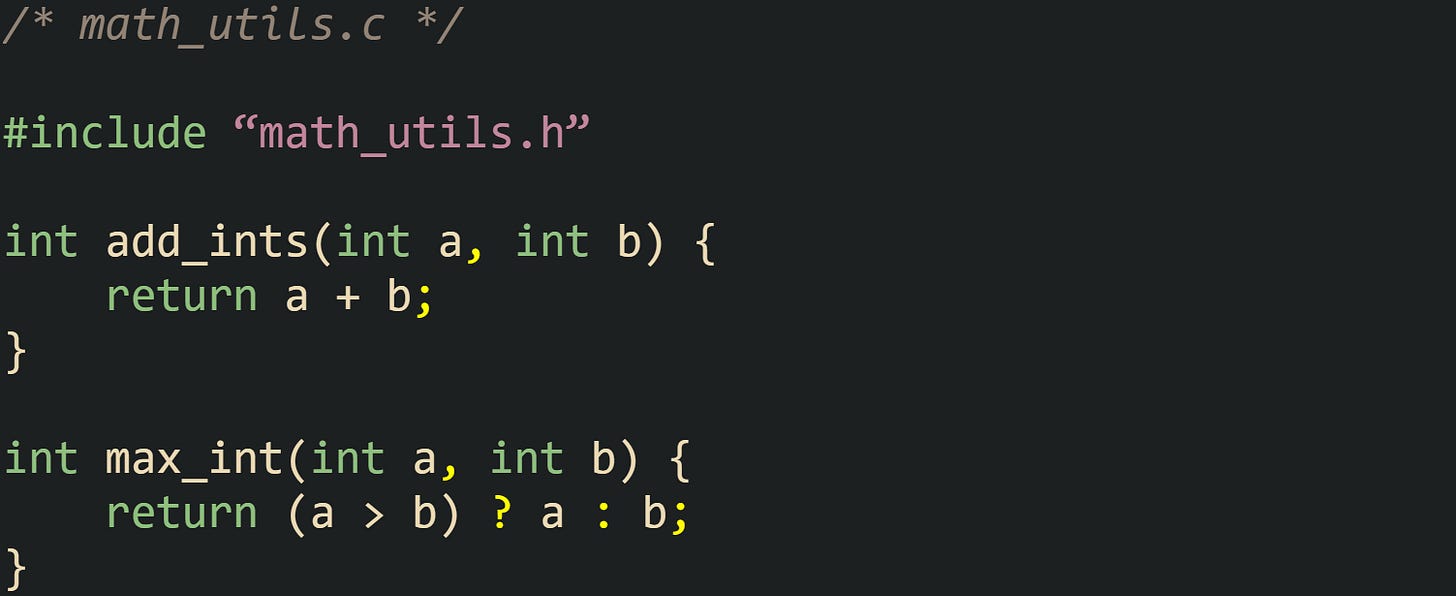

One very small translation unit helps show the order of work. Take this file named config_example.c:

When the preprocessor runs on this file as part of a gcc call, it inserts the full contents of <stdio.h> at the top, replaces each use of GREETING with the string literal, and leaves only ordinary C source for the compiler to parse. The call that brings out this intermediate form looks like this:

The resulting config_example.i file contains a large amount of expanded header text plus the main function with the macro already expanded into a normal string literal. That file does not survive into the final build unless you request it, because toolchains normally keep it in memory or in temporary storage, but it matches what the compiler receives as input.

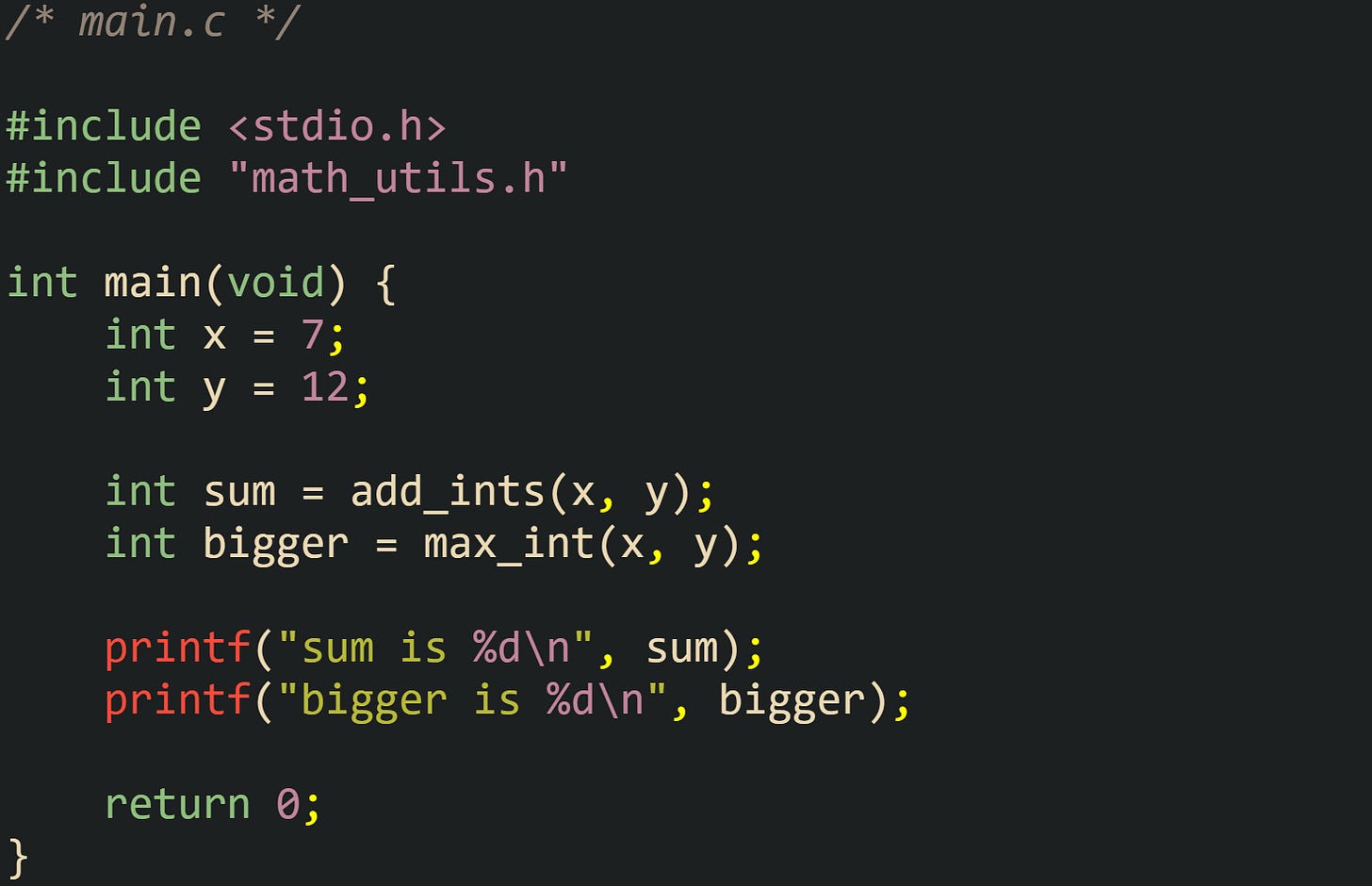

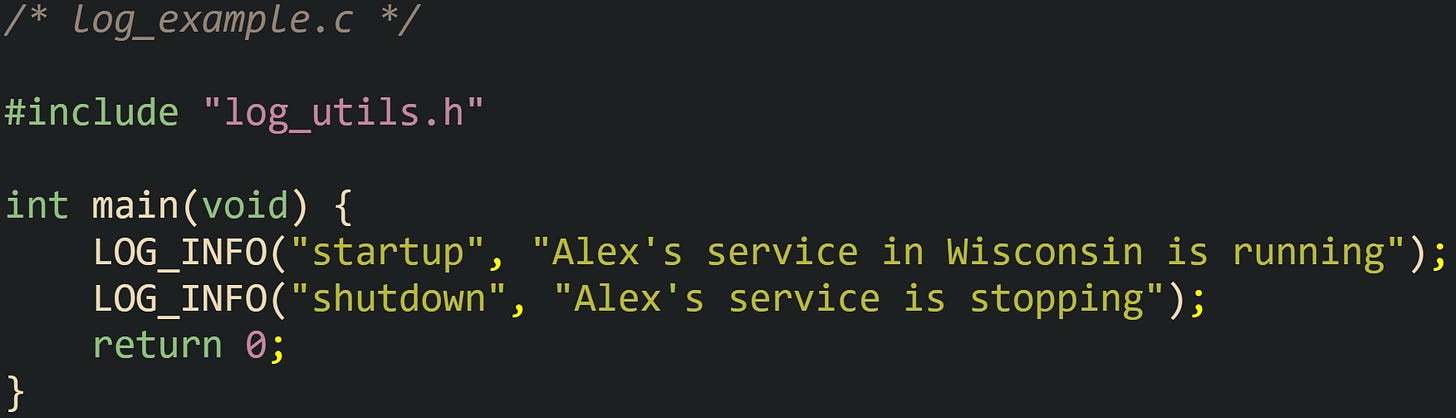

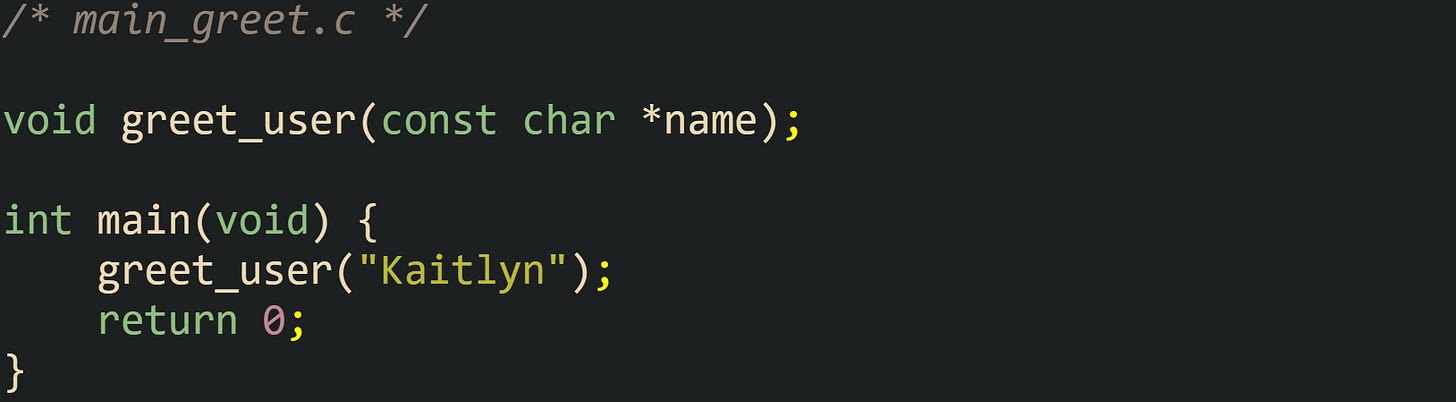

Macros with parameters expand text in a similar way, only with placeholder replacement for macro arguments. Now take this header log_utils.h:

And a source file that relies on it:

Before compilation, the preprocessor replaces the two LOG_INFO calls with expanded printf calls that contain the string literals and the macro body. The compiler never sees LOG_INFO as a function or symbol, only as raw text that turned into calls to printf. Any syntax mistakes in the macro body, such as a missing comma or quote mark, will appear as if they lived in the source file that used the macro rather than in the macro definition itself.

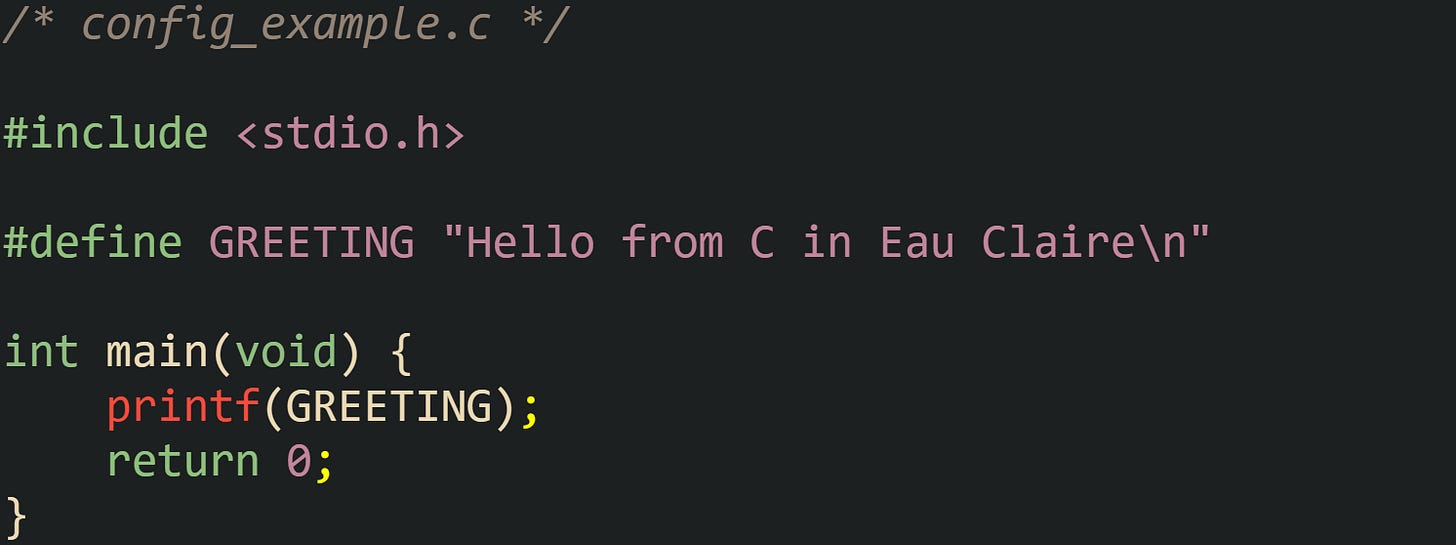

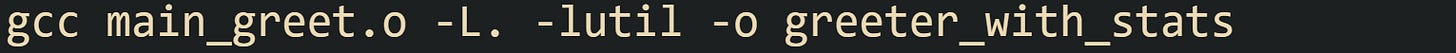

Conditional compilation adds one more dimension. A common pattern introduces extra logging only when a DEBUG macro is defined. This example uses that convention:

If gcc compiles this source with the -DDEBUG option, the preprocessor keeps the version of DEBUG_LOG that expands into printf calls. Without that flag, the macro expands into empty comments, so the compiled translation unit contains no debug messages at all. That means a single source file can therefore produce different compiled behavior based on macro definitions passed from the build system.

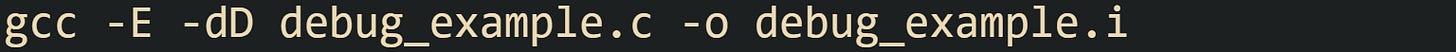

The compiler driver gcc exposes several options that help inspect preprocessor effects. The -E option stops after preprocessing and writes the expanded translation unit, and the -dD flag tells the tool to keep macro definitions in that output, including macros that header files defined. That combination is common when diagnosing how a complex header tree and many macro definitions interact. Command lines look like this:

The resulting .i file contains all source that actually reaches the parser, including the chosen branch of any #if or #ifdef groups, with directives removed. Viewing that file can reveal macro expansions, unexpected include order, or redefinitions that changed the meaning of constructs later in the file.

Many build systems encourage a structure where each .c file is compiled as a separate translation unit, which causes the preprocessor to run for every source file. Projects with large header trees manage that cost through careful header organization and, in some environments, precompiled headers that hold common include sets that rarely change. Those optimizations leave the logical behavior of the preprocessor intact while trimming repeated work during incremental builds.

From Compilation To Linked Executable

After preprocessing, the compiler sees a single expanded translation unit and starts turning that C text into machine level instructions. The work in this stage moves from high level syntax through assembly language and then into binary object files. Once those pieces exist, the linker collects them with any needed libraries and produces an executable that the operating system loader can start as a process.

Compiler Translation To Assembly

The compiler front end begins by turning characters into tokens, such as identifiers, numbers, operators, and punctuation. A parser then checks that those tokens follow C grammar rules and builds internal trees that represent expressions, statements, and function bodies. Type checking verifies that operations match the types involved, such as making sure a pointer is not added to a struct or that an int is not used where a pointer is expected.

After syntax and type checks, the compiler typically lowers the code into an intermediate representation, runs many optimization passes on that form, and finally emits assembly language for a specific instruction set such as x86 64 or AArch64. That assembly describes function entry and exit, register usage, stack layout, and control flow through branches and jumps.

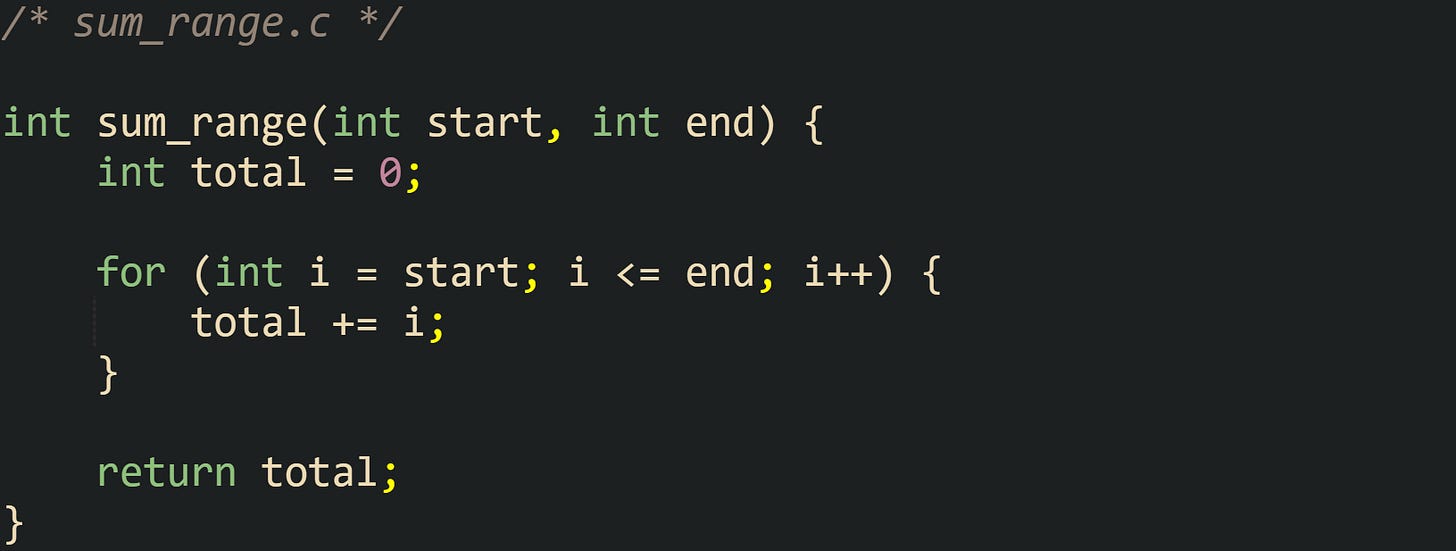

Take a small C file named sum_range.c:

Compilation with:

This produces sum_range.s, which holds human readable assembly. The exact instructions depend on the target architecture and optimization flags, yet some common elements appear in most builds. There will be prologue code that reserves stack space and saves certain registers, a loop that increments i and adds it into total, and an epilogue that restores state and returns to the caller.

Adding optimization flags such as -O2 changes the generated assembly noticeably. The compiler can remove the explicit loop and replace it with arithmetic that computes the sum of an arithmetic series, or at least tighten the loop body and hoist calculations that do not depend on the loop index. That change is visible only in the assembly output and not in the C source, which still describes the loop in a straightforward way with the for statement.

Control flow structures all pass through this same translation pipeline. Conditionals, loops, and function calls in C source turn into labels and branch instructions in assembly. Short if statements often become conditional branches that skip over a block, while switch statements may translate into jump tables that let the processor branch based on an index. Function calls such as sum_range(1, 10) translate into instructions that move arguments into registers or onto the stack according to the platform calling convention, followed by a call instruction that transfers control to the sum_range entry point.

Compilers for C also support function inlining and other transformations that rework the call structure in the assembly output. A call to a small helper function located in the same translation unit can be replaced with a copy of that helper body directly in the caller, which removes call and return overhead at the cost of a slightly larger code section. This tradeoff remains invisible to the source level view, yet it matters to performance and code layout that the final binary presents to the hardware.

Assembly Into Object Files

Assembly files produced by the compiler still live as text. The assembler turns that text into binary machine code and writes it into relocatable object files that usually carry the .o suffix on Unix like systems. Those object files hold sections such as .text for executable code, .data for initialized global variables, and .bss for uninitialized globals that will be zeroed at process start.

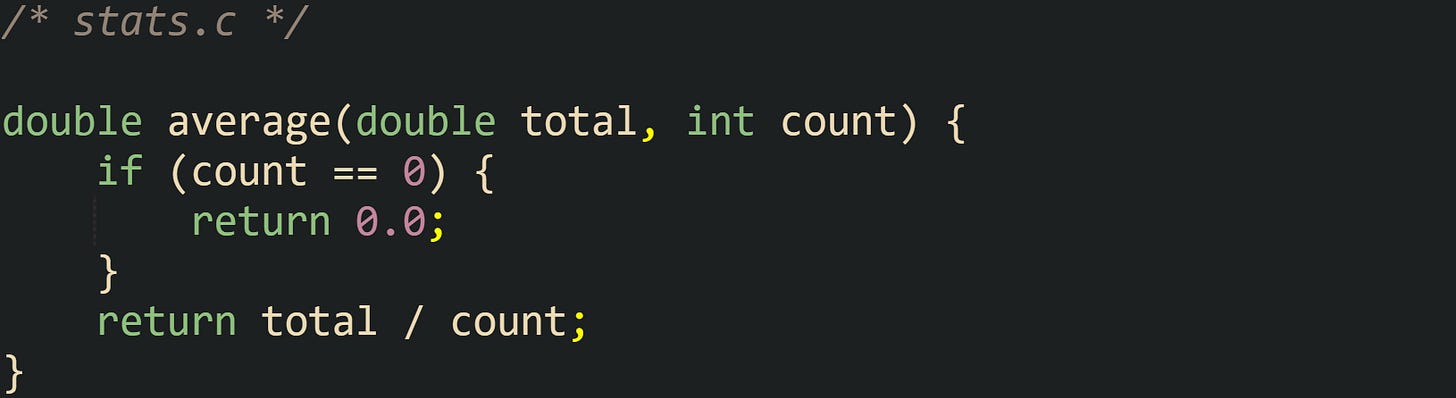

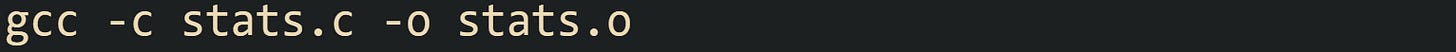

A common development pattern lets the compiler and assembler work in one step. Take a file named stats.c:

Compiling it into an object file uses a command line such as:

That single call runs preprocessing, compilation, and assembly, then leaves stats.o on disk as a relocatable object file. Inside that file, the average function has a symbol entry that names its location in the .text section, and any references to external functions would appear as unresolved symbols that the linker must match later.

Object files also store relocation entries. Those entries mark places where addresses or offsets need adjustment when the linker knows final section placements. For example, a reference to a global variable defined in another object file will have a relocation record so that the linker can patch in the proper address when all objects are laid out in the executable. Without relocation data, code would need to rely on addresses fixed at compile time, which would limit how the linker can place and combine sections. Debug information can be emitted into object files as well. When compiled with a flag such as -g, gcc adds DWARF debug sections that map machine code back to source lines, variable names, and type layouts. That information lets debuggers such as gdb draw a source level view of execution while still working with machine code addresses underneath.

Separate compilation across multiple source files depends on this object file model. File stats.c can be compiled into stats.o, a different file io_helpers.c can become io_helpers.o, and a main file can be built independently. As long as headers keep declarations in sync, the linker later has enough information in the symbol tables to connect calls and data references across those object files. That separation keeps incremental builds manageable, because only changed source files need recompilation, while untouched object files can be reused in the next link step.

Linking With Ld Plus Helper Tools

The linker collects object files and libraries and arranges them into a single binary image. On many Unix like systems the tool named ld performs that linking work, while gcc acts as a convenient front end that passes on all the inputs and default runtime options.

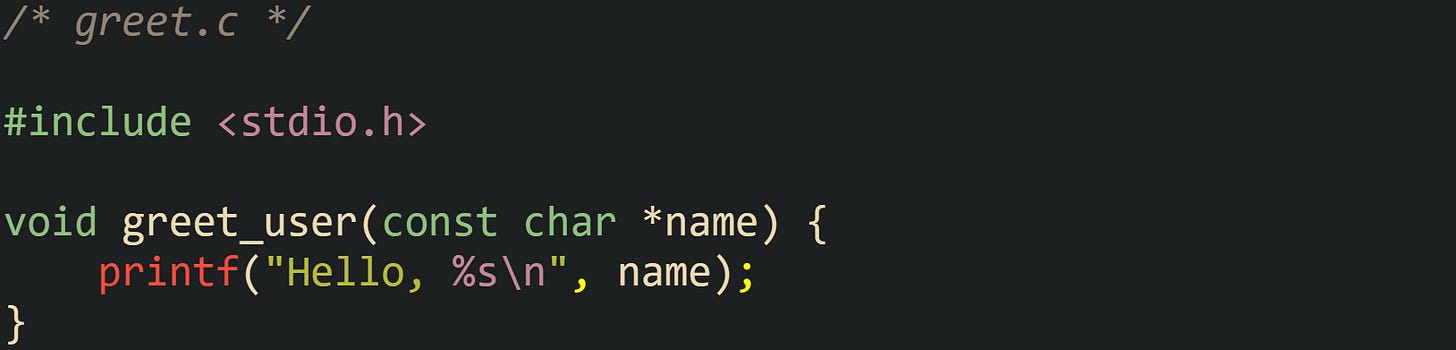

The basic pattern with two source files might look like this. Suppose there is a file greet.c:

And another file main_greet.c:

First, both files turn into object files:

Then a final link step combines them into an executable:

The gcc driver in that last command calls ld with the two object files, startup code for the C runtime, and default C library options. The linker resolves the greet_user reference in main_greet.o by finding the greet_user symbol definition in greet.o, adjusts addresses in relocation entries, and writes an executable in the platform format, such as ELF on Linux.

Libraries enter the picture when code depends on functions that live in separate archives or shared objects. A static library is a collection of object files stored in an archive created with a tool such as ar. Suppose greet.c and stats.c are turned into a static library named libutil.a. After compiling them to greet.o and stats.o, an archive command such as:

That creates that library file. Linking an executable that uses greet_user and average then looks like:

The -L. flag directs the linker to search the current directory for libraries, and -lutil requests libutil.a. The linker pulls in only those object files from the archive that satisfy unresolved references from the existing link set, so unused functions in the library do not increase the size of the final executable.

Dynamic linking relies on shared objects instead of archives of plain object files. Commands that build shared libraries usually use compiler flags such as -shared combined with -fPIC so that the resulting code can load at varied base addresses. Linking against such a shared object stores references that the dynamic loader resolves when a process starts. On Linux, an executable linked against libc.so records that dependency, and at startup, the loader maps both the main executable and required shared libraries, then patches import tables so that calls reach the proper shared library entry points.

Options passed to gcc guide the linker toward different link products. A command with -static instructs the driver to ask ld for a purely static executable that does not depend on shared libraries, while -shared requests a shared object as the primary result instead of a standard executable. On many modern systems, default builds use position independent executables, which alters how the linker arranges code and data so that address space layout randomization features in the operating system can relocate the process image at different base addresses on different runs.

After linking, the operating system loader treats the final binary as a structured container. The loader maps segments such as the code segment and data segment into memory, sets up the stack and other process state, and then transfers control to the startup routine installed by the C runtime. That routine performs initialization work such as running startup functions registered by the toolchain and libraries, setting up argc and argv, and then calling the user defined main function in the executable.

Conclusion

The C compilation flow takes a .c file through preprocessing, compilation to assembly, assembly to object code, and linking into a binary that the operating system can load. Preprocessing expands headers and macros into a translation unit, the compiler turns that translation unit into architecture specific assembly, the assembler writes machine code and relocation records into object files, and the linker resolves symbols across those objects and libraries to produce an executable with a layout the loader can map into memory and start at main.

![/* log_utils.h */ #ifndef LOG_UTILS_H #define LOG_UTILS_H #include <stdio.h> #define LOG_INFO(tag, msg) \ printf("[INFO] (%s) %s\n", tag, msg) #endif /* log_utils.h */ #ifndef LOG_UTILS_H #define LOG_UTILS_H #include <stdio.h> #define LOG_INFO(tag, msg) \ printf("[INFO] (%s) %s\n", tag, msg) #endif](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!GpL3!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0b982175-4a05-4367-97e5-4b4ac71f8128_1510x608.png)

![/* debug_example.c */ #include <stdio.h> #ifdef DEBUG #define DEBUG_LOG(msg) printf("[DEBUG] %s\n", msg) #else #define DEBUG_LOG(msg) /* no logging in release builds */ #endif int main(void) { DEBUG_LOG("starting calculation for Pippin"); printf("Hello\n"); DEBUG_LOG("finishing calculation for Pippin"); return 0; } /* debug_example.c */ #include <stdio.h> #ifdef DEBUG #define DEBUG_LOG(msg) printf("[DEBUG] %s\n", msg) #else #define DEBUG_LOG(msg) /* no logging in release builds */ #endif int main(void) { DEBUG_LOG("starting calculation for Pippin"); printf("Hello\n"); DEBUG_LOG("finishing calculation for Pippin"); return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!UrcV!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd06a6deb-45e4-47ab-a462-1638ae33f999_1633x894.png)

This breakdown of the compilation pipleine is really solid. The way object files store relocation entries so the linker can patch addresses later is something I always found fascinating when debugging linking errors at my previous job. It's wild how much coordination happens between tools that most devs never directly see, yet those relocation records are basically what lets seperae compilation actually work.