Control flow in C decides which statements run and in what order, and every if, switch, or loop changes that path through a function. The compiler turns these constructs into conditional jumps, repeated sections, and exits in machine code, while the source code stays focused on conditions, blocks, and braces. Control expressions in if and switch guide branches, and loop forms such as for, while, and do while keep execution moving or stop it when a test expression says so. The behavior of break and continue alters that route through the code, and switch fall through shows how execution can move from one case to the next when no break appears.

Branching With Conditional Statements

In C, branching steers execution through source code so that only some statements run on a given pass and others are skipped. Instead of every line running in order from top to bottom, control flow bends around if tests and jumps directly into switch selections. The language treats branch conditions as expressions that end in either zero or nonzero, so any scalar expression can act as a test. Relational and logical operators help build those tests, and the result then decides which block of code runs next or which block is skipped entirely.

If Statements With Conditions

An if statement in C takes a single expression inside parentheses, evaluates it, and checks whether the final value is zero or nonzero. Zero means false. Any nonzero value means true. That rule applies no matter whether the expression is a direct variable reference, a comparison, or a function call that returns an integer.

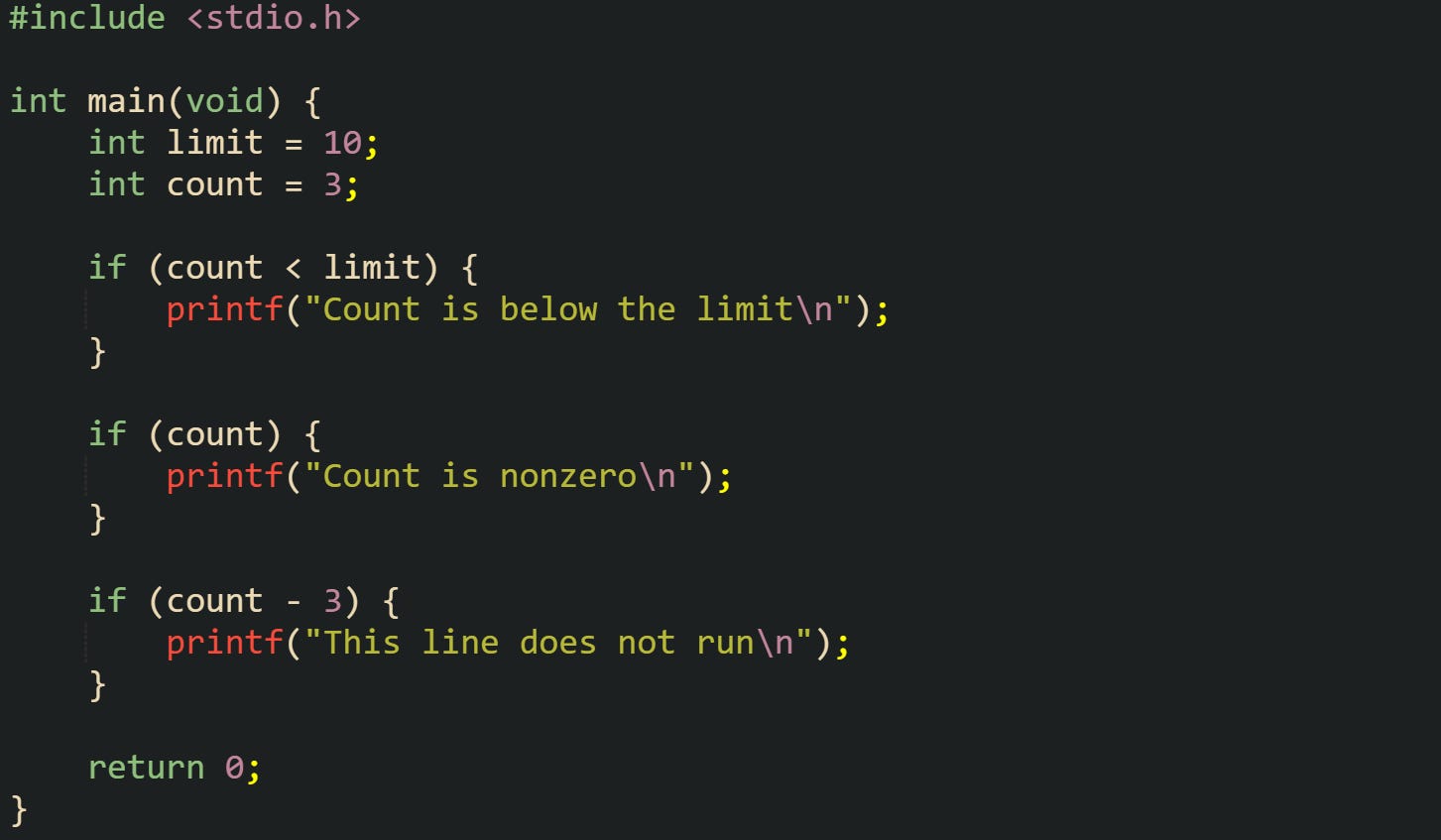

That idea comes through in a short piece of code where count is checked in a few different ways against zero and a limit.

Firstly, the test compares count and limit. The expression count < limit evaluates to 1 here, so the printf call runs. The second if checks count directly, which yields 3. That nonzero value is treated as true, so the second message prints as well. The expression count - 3 yields 0, so the third if is false and its body is skipped.

Relational operators such as <, >, <=, >=, ==, and != always yield either 0 or 1. Logical operators && and || also yield 0 or 1 and short-circuit. Short-circuiting means that expr1 && expr2 stops as soon as expr1 is false, because the whole expression cannot become true in that case. For expr1 || expr2, evaluation stops as soon as expr1 is true, because the result is then fixed at true. That behavior affects side effects, because a function call inside the second expression might never run.

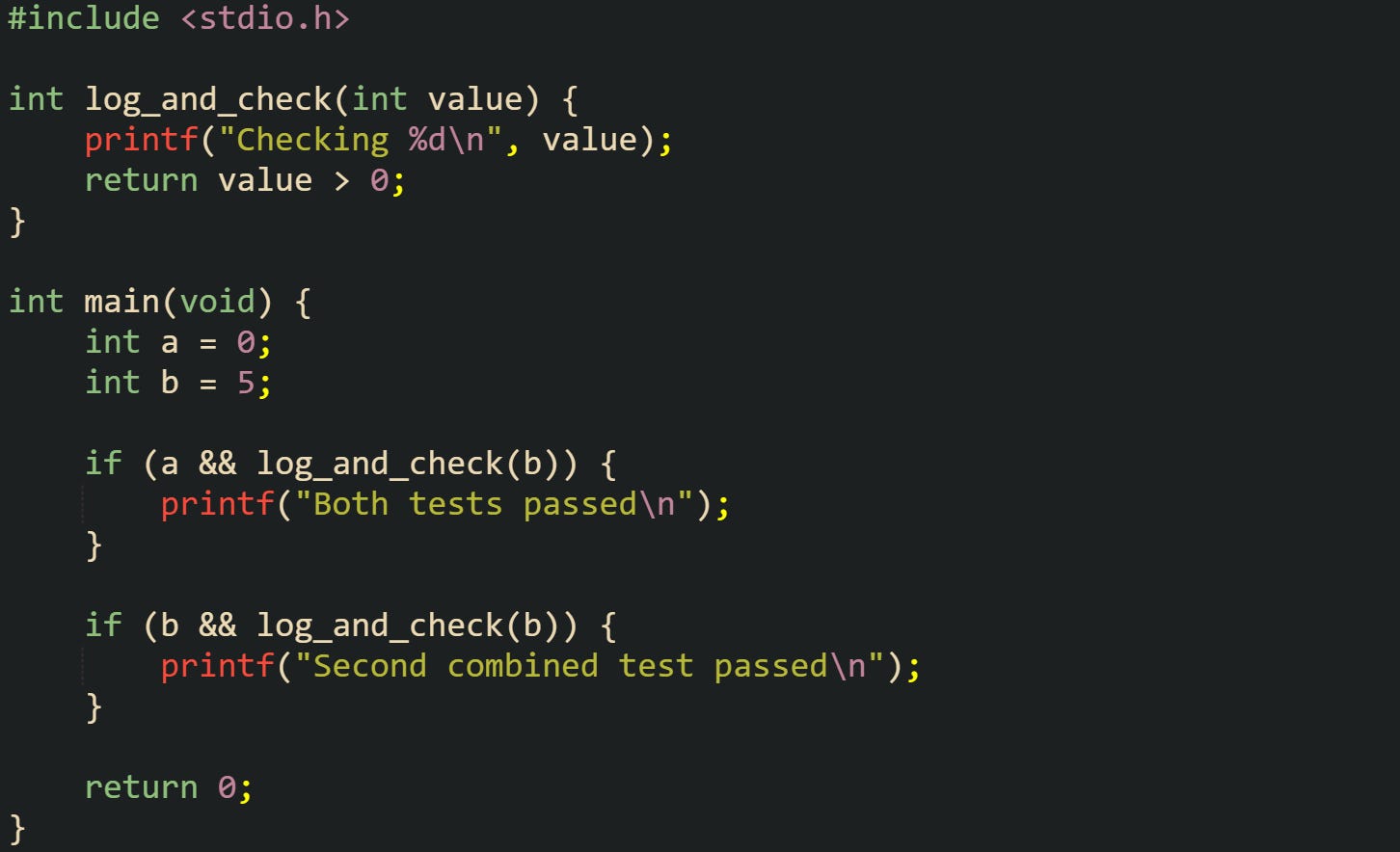

This example centers on short circuit behavior so you can see when a helper function is called and when it is skipped:

In the first if, the expression a && log_and_check(b) evaluates a first. Because a is zero, the result of the && expression is already false, so log_and_check never runs. In the second if, b is nonzero, so log_and_check is called and the message Checking 5 appears.

Parentheses let you group parts of a condition so that the compiler evaluates the pieces in the order you intend. Operator precedence rules still apply, but explicit grouping is often clearer to readers and avoids subtle surprises around mixes of &&, ||, and comparison operators. The condition inside if can also involve functions that return _Bool or use stdbool.h with bool. The language still treats zero as false and nonzero as true, but those types help convey intent in header files and function signatures.

If Else Chains In C

Many situations need more than a single yes or no branch. C solves that with else if and else so that several exclusive cases can sit in one chain. The language treats the chain as one unit evaluated from top to bottom. As soon as one condition is true, its block runs and the rest of the chain is skipped during that pass.

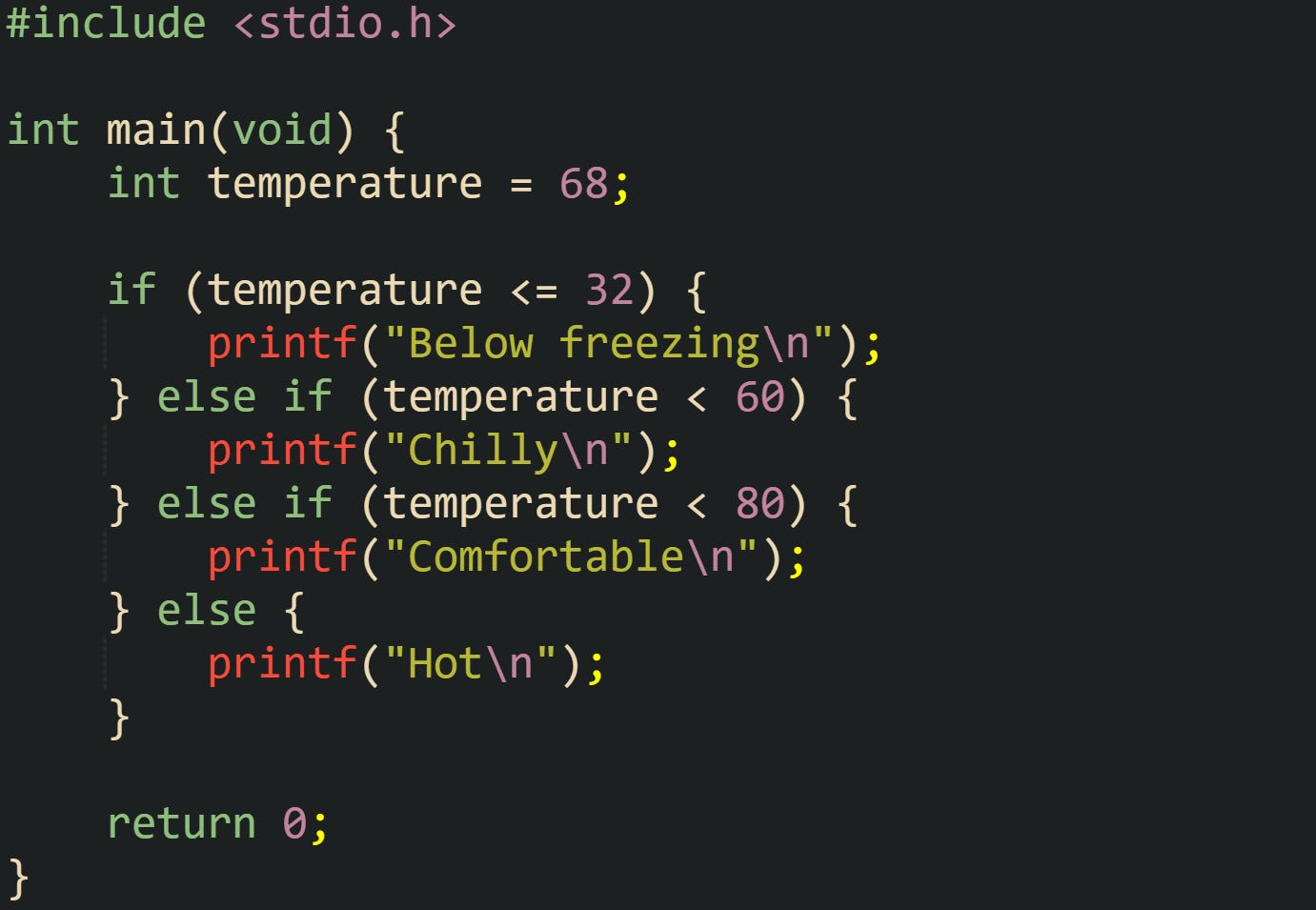

This chain that assigns text labels to a temperature reading gives a good visual of how if, else if, and else are processed from top to bottom:

The run through this chain starts with temperature <= 32. That condition is false, so control moves to temperature < 60. That test is also false, so the third test temperature < 80 runs, evaluates to true, and triggers the "Comfortable" branch. After that, the else block does not run, and no other condition in the chain is checked.

Only one branch in such a chain can run on a single pass, because the language specification states that else always associates with the nearest unmatched if, and the control flow rules skip all following else if and else parts once a true condition has been found earlier in the same chain. The last else acts as a catch-all for every remaining case. Some chains omit it and simply fall off the end when no condition is true, which is useful when there is no meaningful default action. In other cases the else branch logs unexpected data or sets a safe fallback value.

Braces group statements into a block so multiple lines of code can run as one branch body. If braces are omitted, only the next statement belongs to that branch. That rule can lead to unintended behavior when indentation suggests one grouping and the compiler follows another.

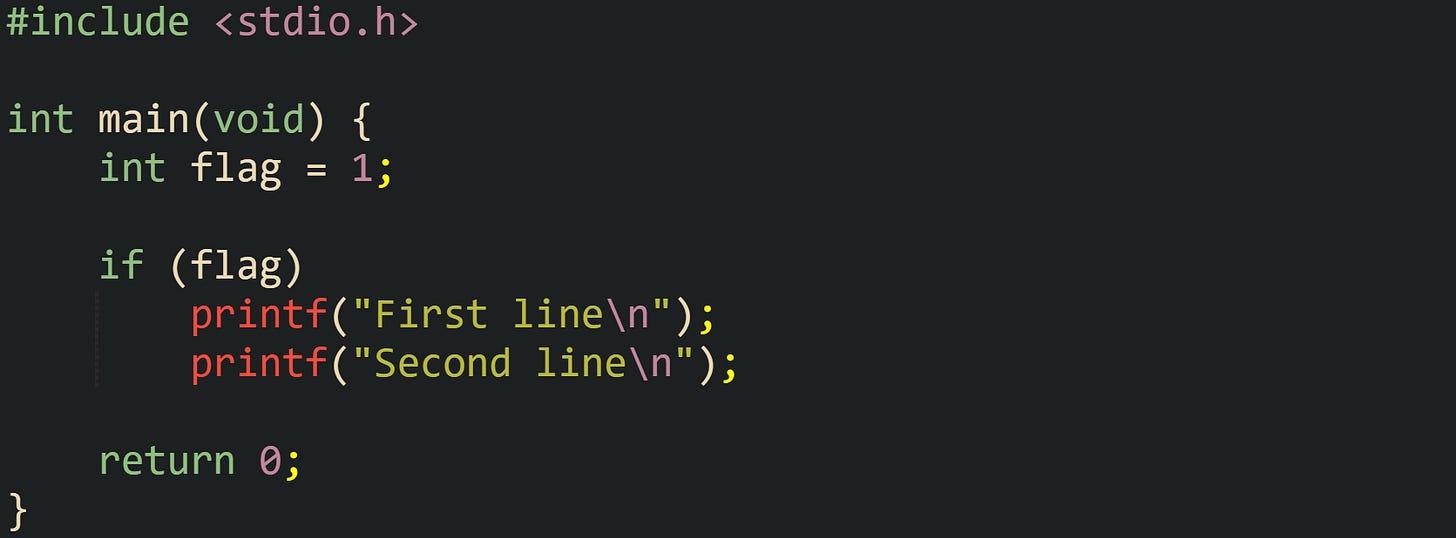

This flag shows what happens when braces are left out and only the next statement falls under the if:

Only the first printf call is guarded by the if. The second call runs every time because it is not part of the controlled statement. Braces remove this ambiguity and help readers see what belongs to the branch.

Conditions in an if / else if chain routinely call helper functions that return integer status codes. Those calls still run even if they eventually evaluate to false. For instance, if (read_config() == 0) will always call read_config when execution reaches that point, then base the branch decision on its return value.

Switch Statement Mechanics

A switch statement selects among many constant cases based on one controlling expression. That expression is evaluated once at the top, then the implementation jumps directly to the matching case label if there is one. Types allowed for the controlling expression include integer types, enumeration types, and compatible character types that can be converted to an integer representation.

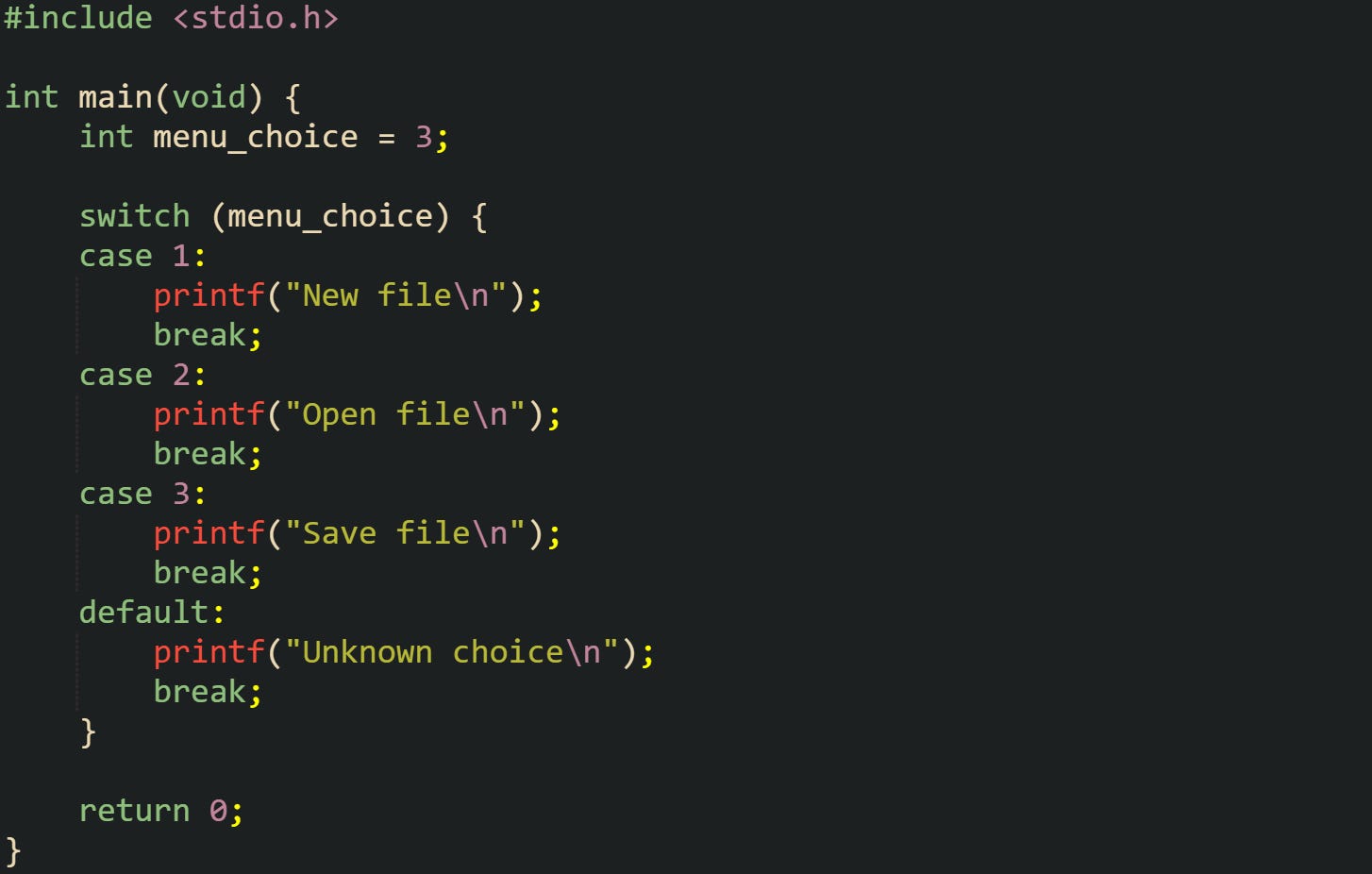

To see how a switch selects among menu options, this code uses an integer choice that maps to a few text messages:

The expression menu_choice is evaluated first. If it equals 3, the controlling value matches case 3 and execution jumps directly to that label. None of the statements in the earlier cases run. After printing "Save file", the break transfers control out of the switch block to the statement that follows it.

Case labels must use constant expressions that the compiler can evaluate at compile time. They cannot depend on variables that change at runtime, and the compiler rejects duplicate values in the same switch. Enumeration constants work well here because they carry names but compile to integer codes.

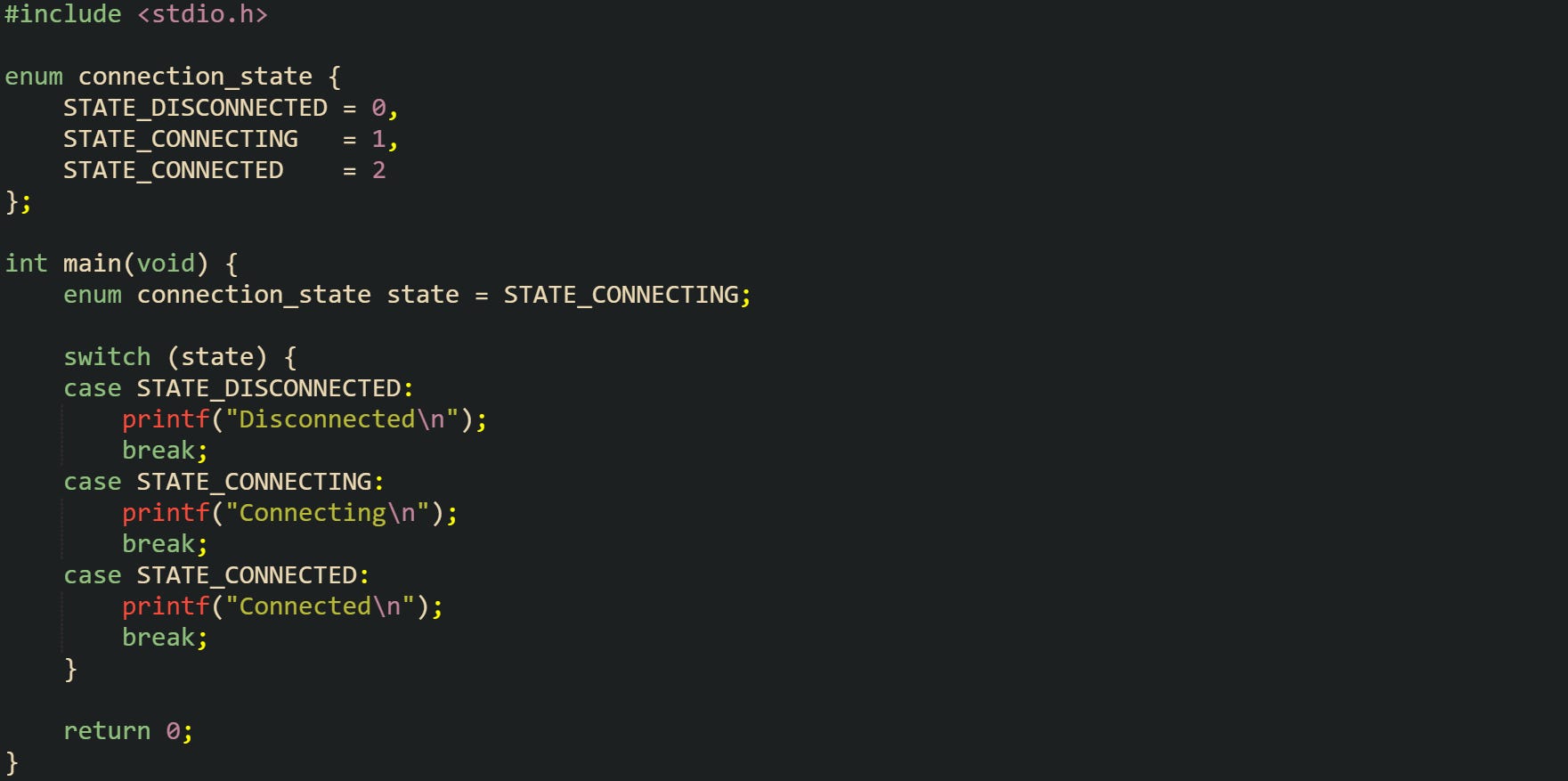

Now let’s look at a enum variant that uses named states for a connection and lets the switch statement branch on those symbolic values instead of raw integers:

The default label, when present, acts as the branch taken when no case constant matches. Its position inside the switch block does not affect which values reach it, only where execution continues when that branch is chosen.

At runtime, the switch statement evaluates its controlling expression and then transfers control to the matching label inside the block. From the first matching label, control flows through the block until a break, return, or other statement that leaves the block runs.

Switch Fall Through With Break

One feature that stands out in C switch statements is fall through. After entering at a matching case label, execution keeps running through later labels until something interrupts it. Only break, return, goto, or reaching the closing brace of the switch stops fall through. If the switch sits inside a loop, continue can also transfer control out of the switch by continuing the loop. That behavior is deliberate and supports compact handling of groups of related cases, but missing break statements can lead to effects that surprise readers.

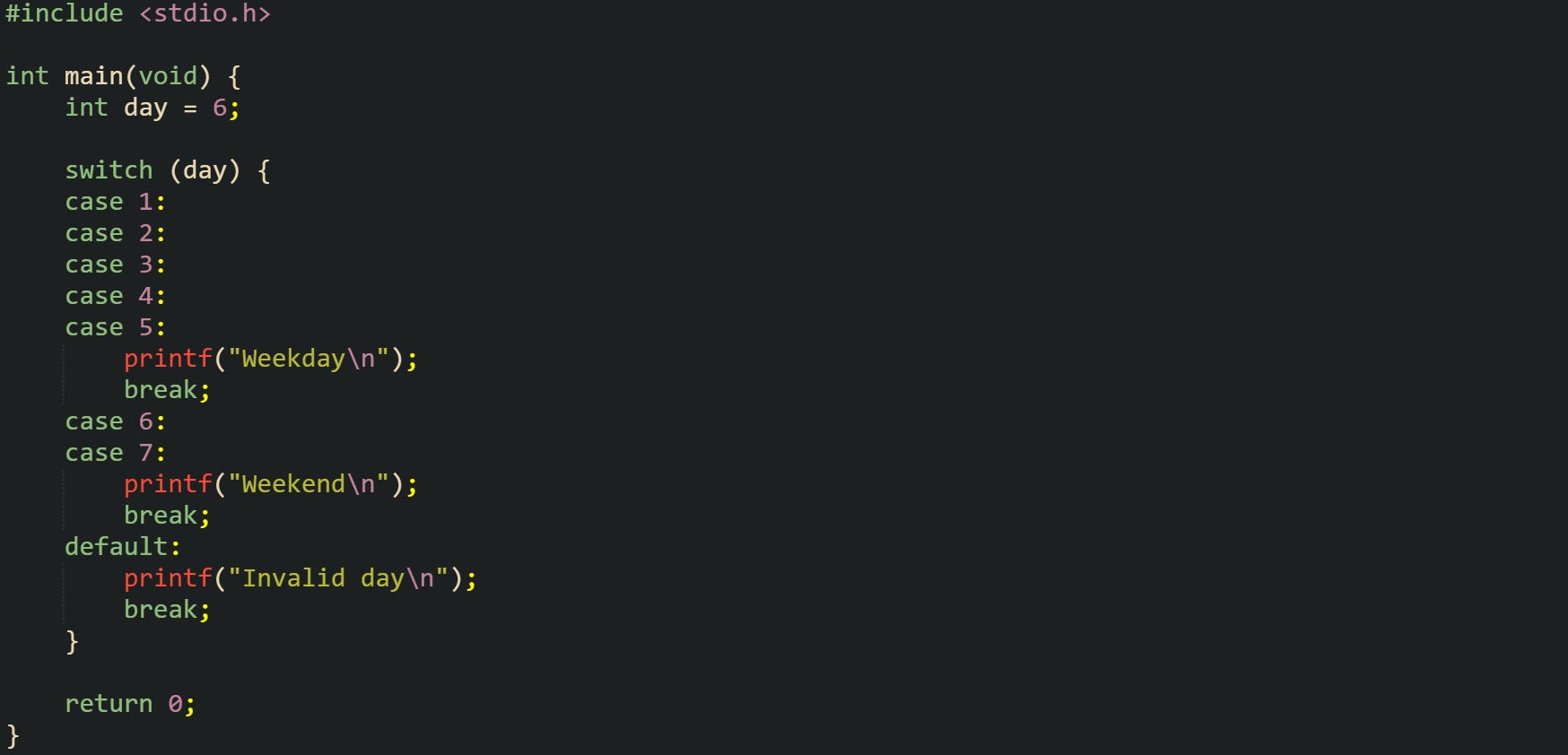

Groupings of case labels can be seen in a small calendar style switch that treats weekdays and weekend days differently while sharing bodies:

When day equals 6, control jumps to case 6, then continues into case 7 without stopping, then runs the printf call labeled "Weekend", and finally hits break which exits the switch. Grouped case labels share one body this way, which keeps repetitive code in one place.

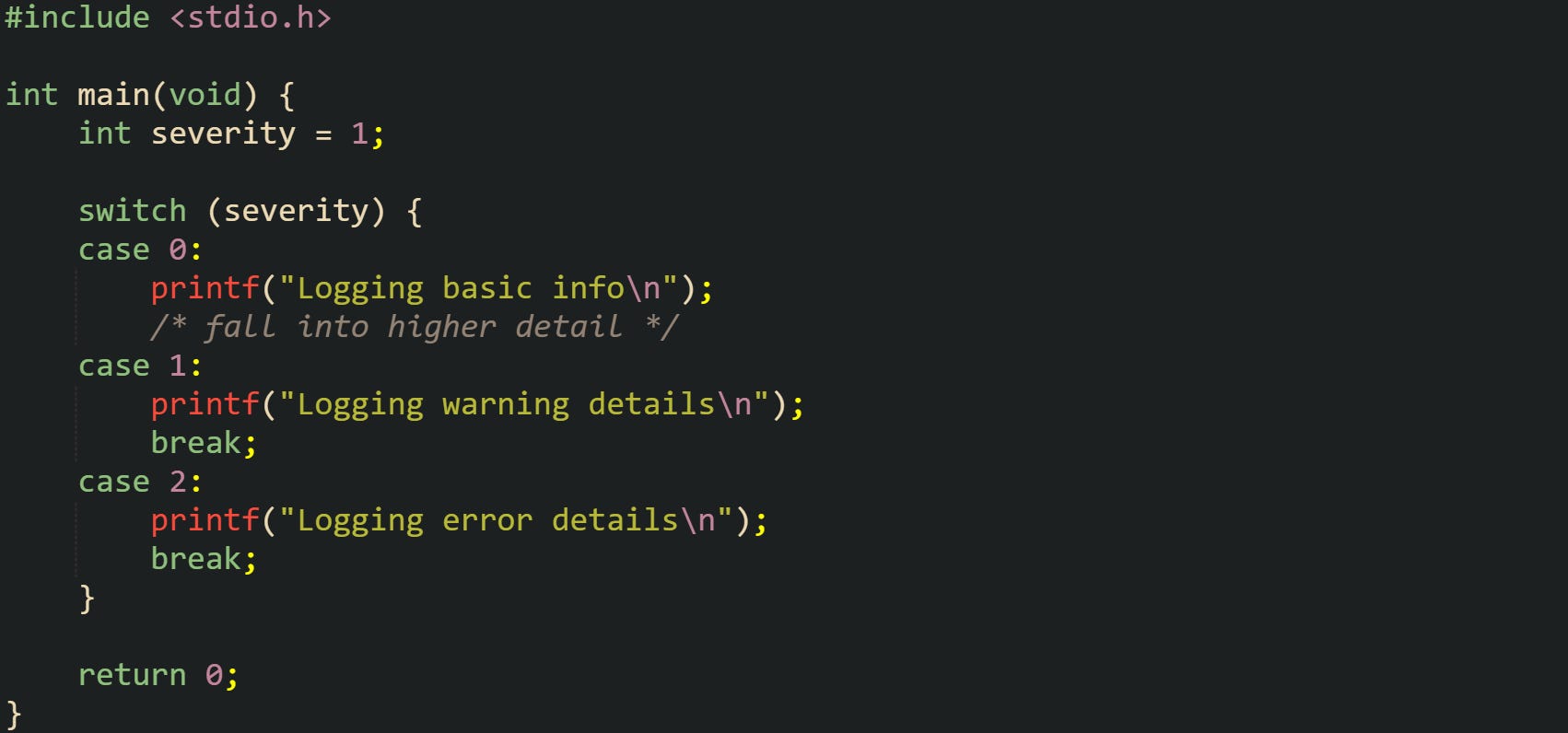

Fall through can also be intentional between bodies that do some shared work before diverging.

When severity is 0, both messages print because control flows from case 0 into case 1 before reaching break. Many codebases add a comment such as /* fall through */ next to intentional fall through so readers can tell that it is deliberate. C23 adds the standard attribute [[fallthrough]]; that can appear at the end of a case body to signal the same intent to compilers and static analysis tools.

Accidental fall through happens when a branch is expected to end but has no break. That leads to extra work that only runs for some case values, which can make bug reports hard to trace. Careful placement of break statements and consistent style around fall through comments or attributes helps prevent that problem.

break inside a switch always exits only that switch, not an outer loop, and execution continues at the first statement after the block. The continue statement is only valid inside a loop. If a switch sits inside a loop and contains continue, that statement applies to the innermost surrounding loop. A switch that is not inside any loop cannot contain continue at all.

Loop Control In C

Code in C can run the same block of statements repeatedly while a condition holds or while some counter walks through a range of values. Instead of writing the same fragment several times, the source code spells out how to start, how to keep going, and when to stop. The language has three core loop forms for this, while, for, and do while, and all three rely on expressions that end up as zero or nonzero. Inside those bodies, break and continue give extra control over when a loop finishes or skips ahead.

while Loop Behavior

The while loop form checks its condition expression before every pass, including the first. If that expression is false on the very first check, the body does not run at all. This structure fits situations where the number of passes is not fixed ahead of time, but the rule to stop can be written as a condition in one place.

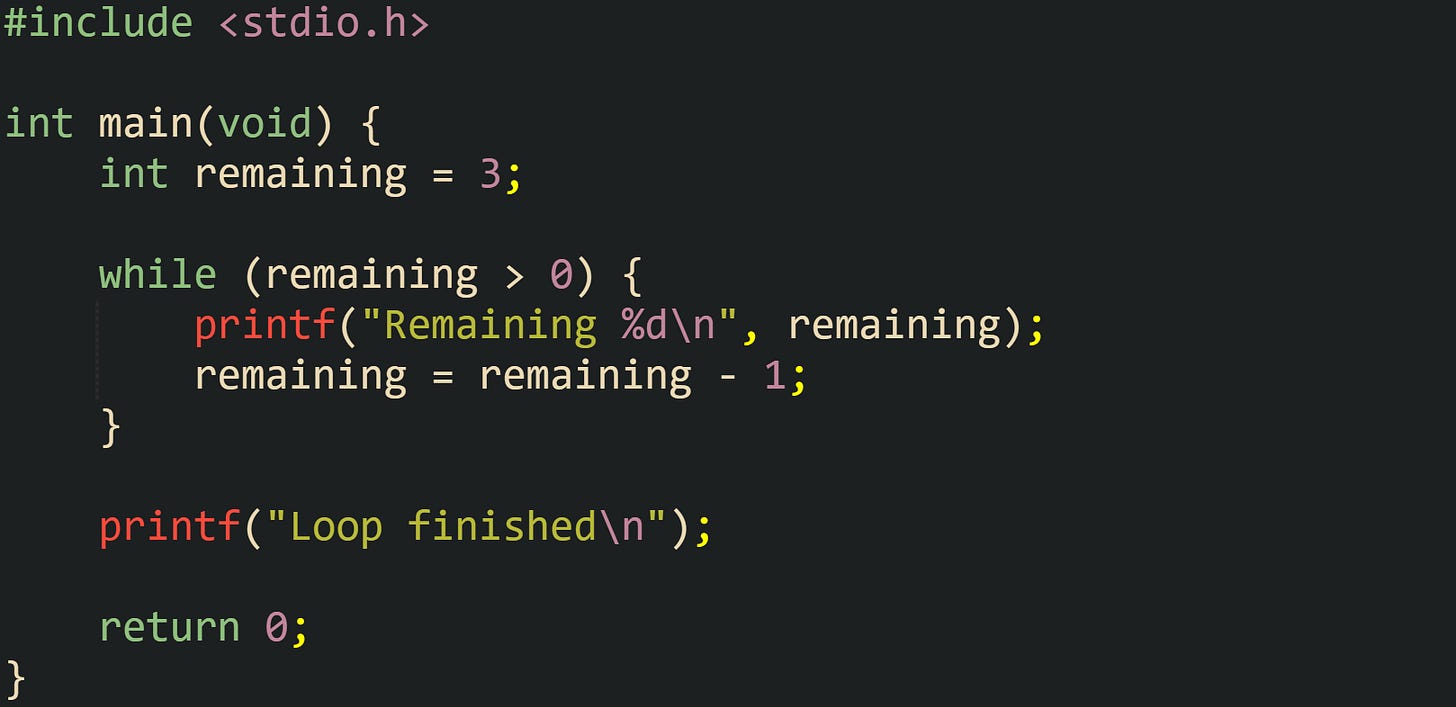

Take this countdown that follows shows this pattern in action:

For that, the condition remaining > 0 is evaluated first. If it is true, the body runs, prints the current value, and decrements it. Control then goes back to the top of the loop, the condition is evaluated again, and the cycle repeats. As soon as remaining reaches 0, the condition turns false, and execution jumps to printf("Loop finished\n"); after the loop body.

Conditions in while loops follow the same truth rule as if statements. Any scalar expression is allowed, and zero means false while any nonzero value means true. Logical operators can combine conditions, which affects how long the loop continues to run.

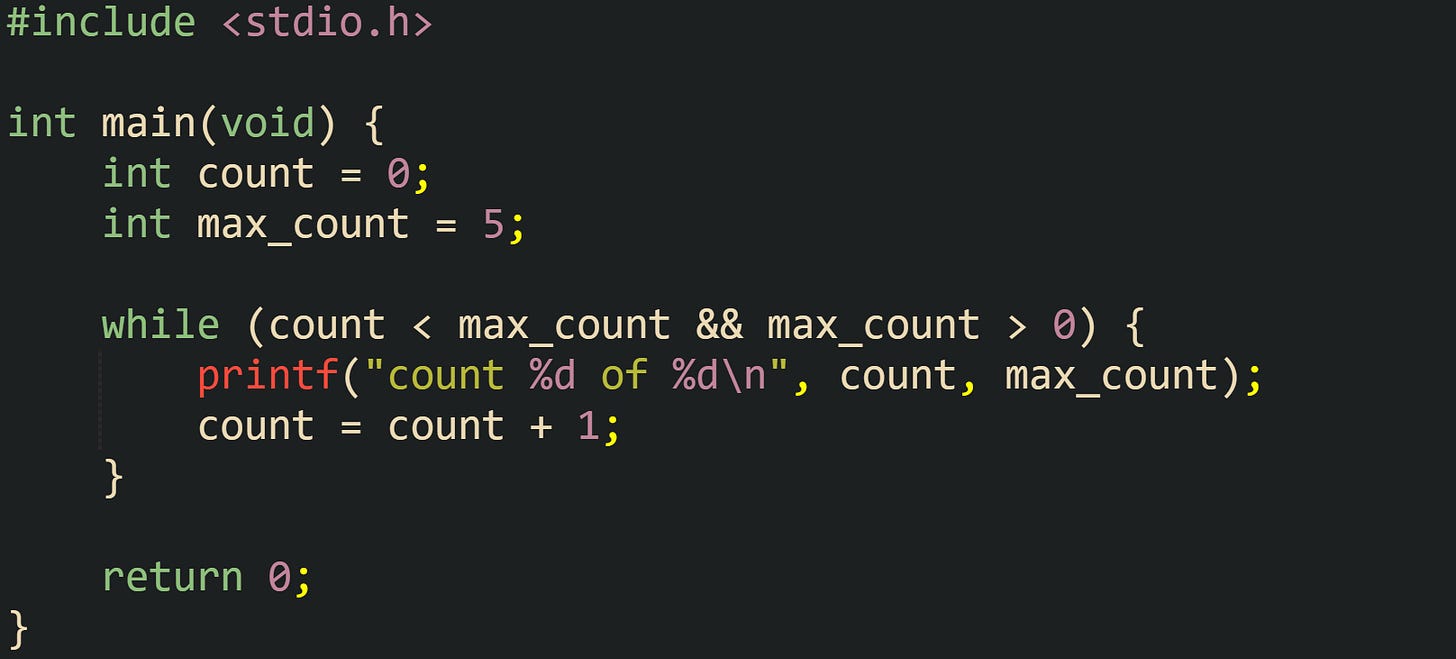

The combined test count < max_count && max_count > 0 must remain true for another pass to start. Short circuit behavior of && still applies, so the second half of the expression is skipped when the first half is false.

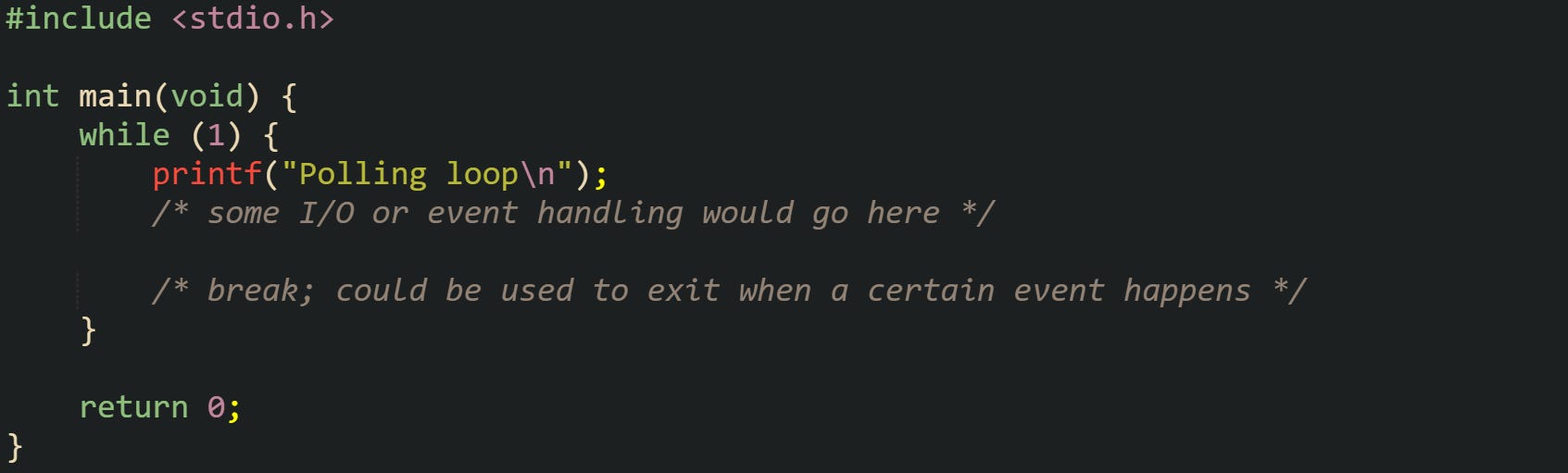

If the state inside the loop body never changes in a way that makes the condition false, control never reaches the statement after the loop. That situation gives an endless loop.

That loop keeps printing and performing its work until something inside it triggers a break, a return, or a call that exits the process. Many long-running services in C start from a loop like that and stay in it while work is available.

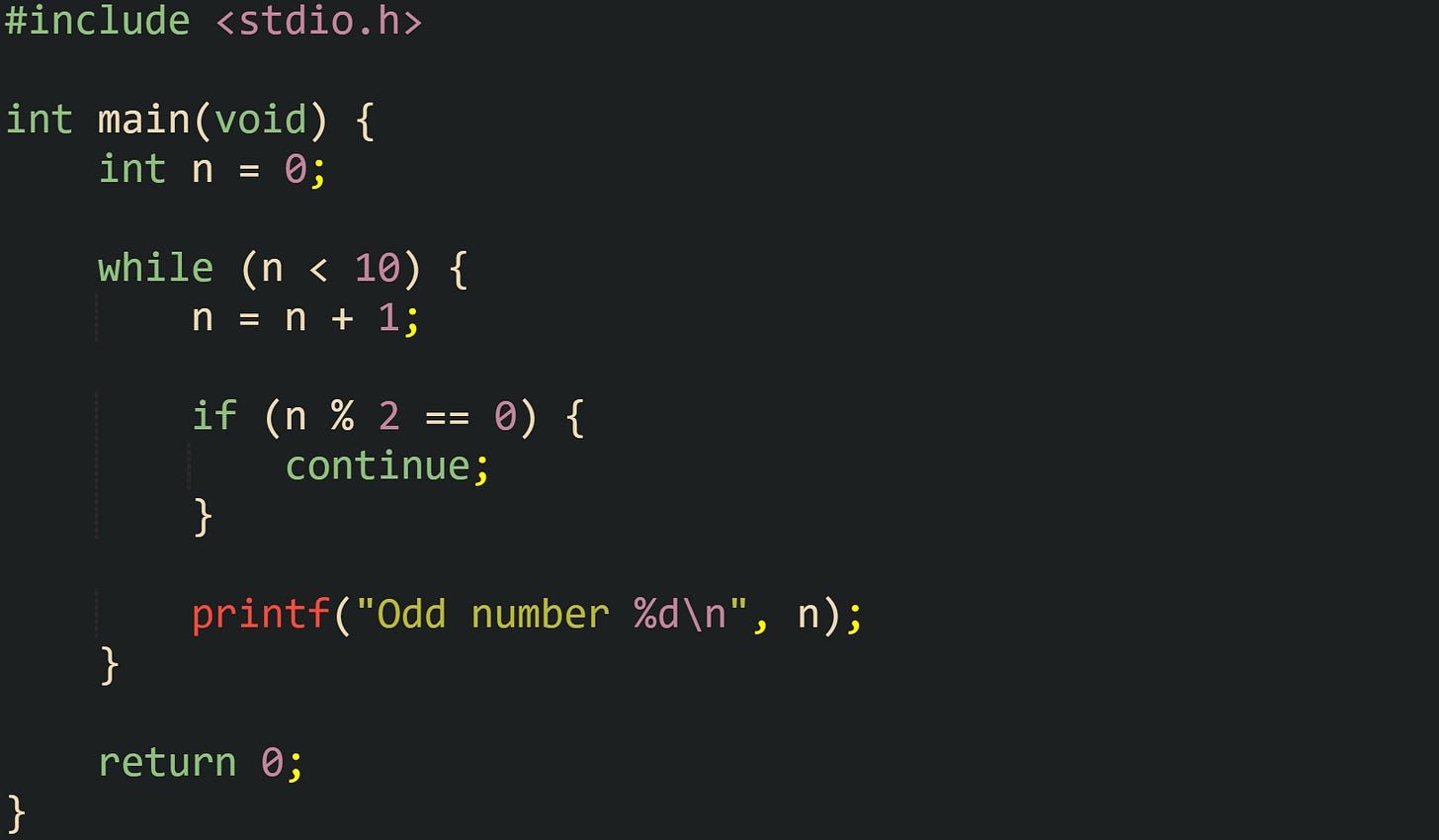

The continue statement can end a single pass early and jump straight to the next condition check. When continue runs, the rest of the body is skipped for that pass, and the loop decides based on the condition whether another pass should begin:

That loop above increments n at the start of every pass. When n is even, the continue statement runs, and the printf call is skipped, so only odd numbers reach the output.

for Loops In Practice

The for loop form brings three pieces of loop control into one line: an initialization expression, a condition, and an update expression. All three appear in the header, which makes it easy to see the life cycle of the loop variable in one place. The execution order stays the same no matter what expressions go there.

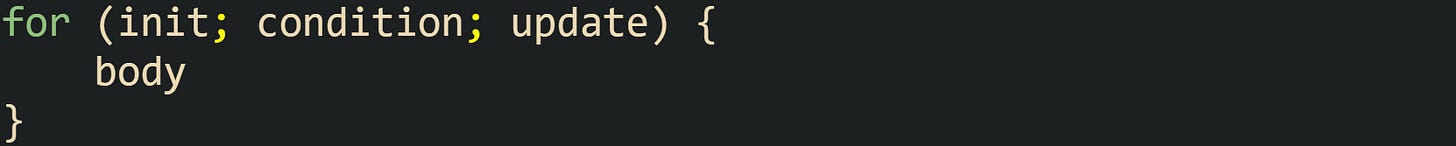

The general form looks like this:

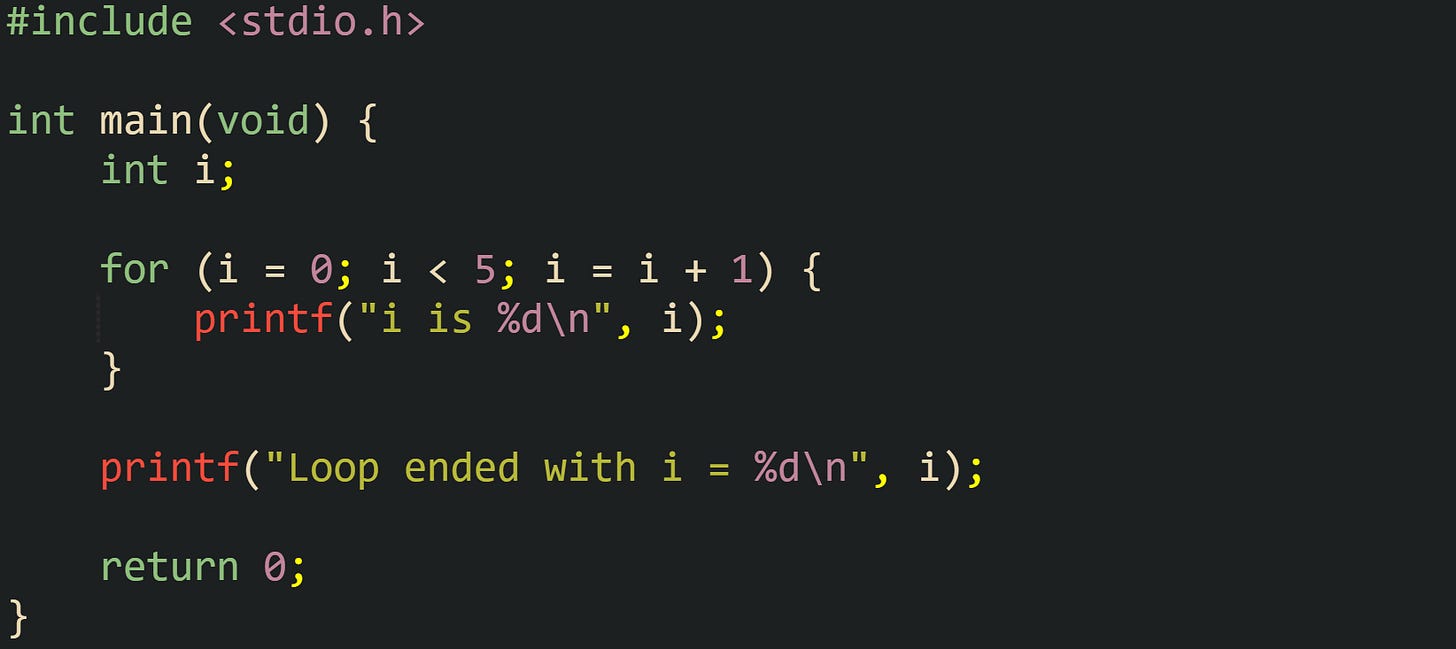

The count-up loop that follows makes the control order easy to see:

The initialization i = 0 runs exactly one time before the first condition check. The condition i < 5 is evaluated before every pass, including the first. If that expression is true, the body prints the value and finishes, then the update i = i + 1 runs. After the update, control returns to the condition check at the top. When i < 5 is false, the loop ends, and execution moves on to the statement after the loop body.

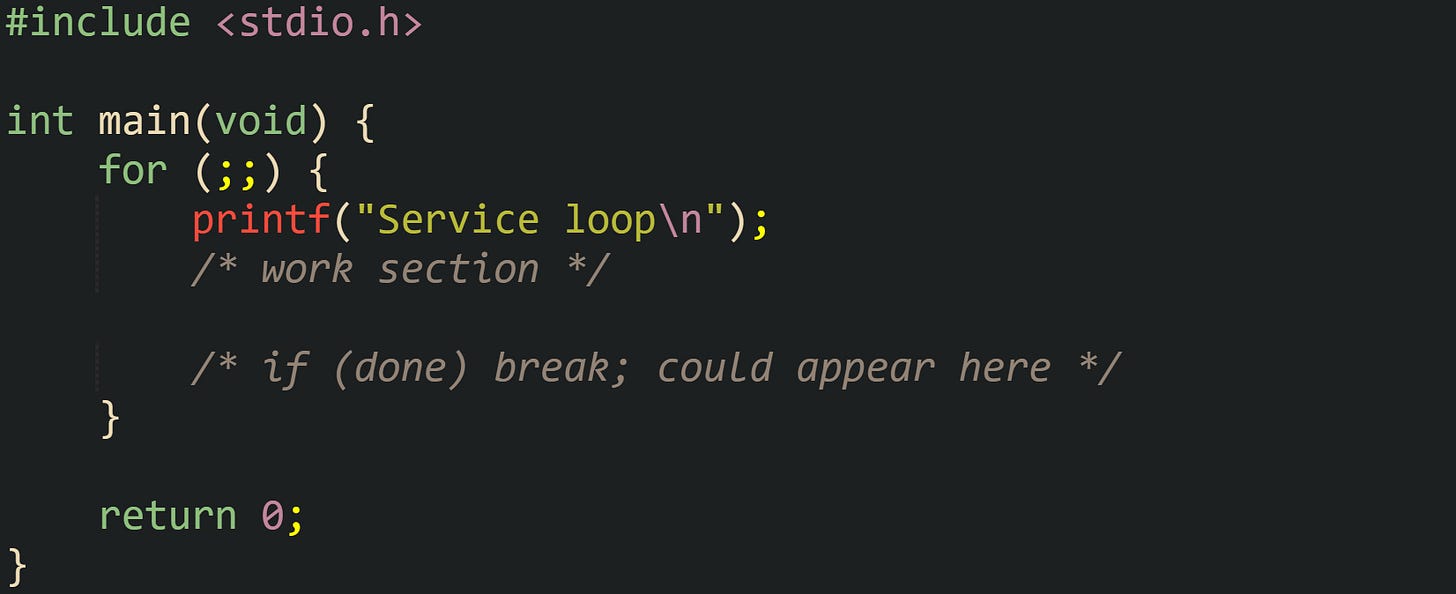

Each of the three fields in the for header may be empty, but the semicolons must remain. Endless for loops are common in systems code and use empty slots this way.

When the condition field in the center position is empty, it is treated as true, so the body runs repeatedly until a break, return, or other exit is encountered.

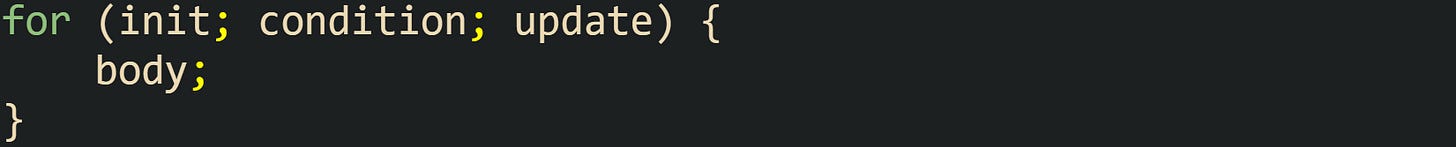

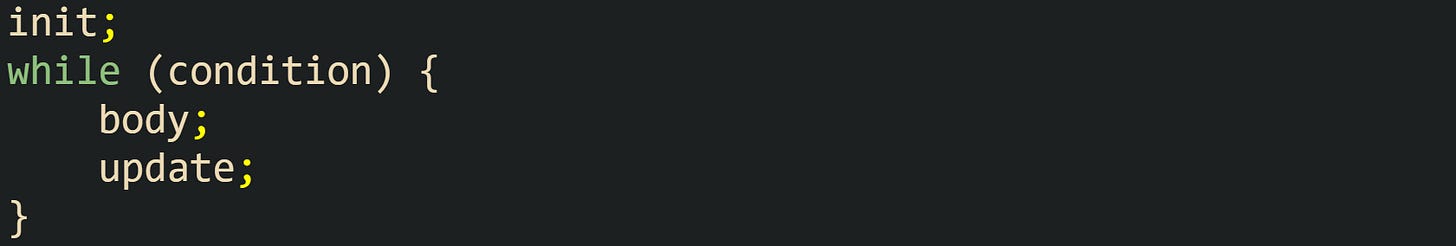

The language standard defines for in terms of while, which helps build a mental model. When a loop is written like this:

It behaves as if the compiler had expanded it to this form:

That equivalence explains how continue behaves. When continue runs inside the for body, it causes control to jump to the update expression, run it, and then perform the condition check, skipping any statements that followed continue in the body on that pass. A break still exits the loop entirely and sends control to the first statement after the block.

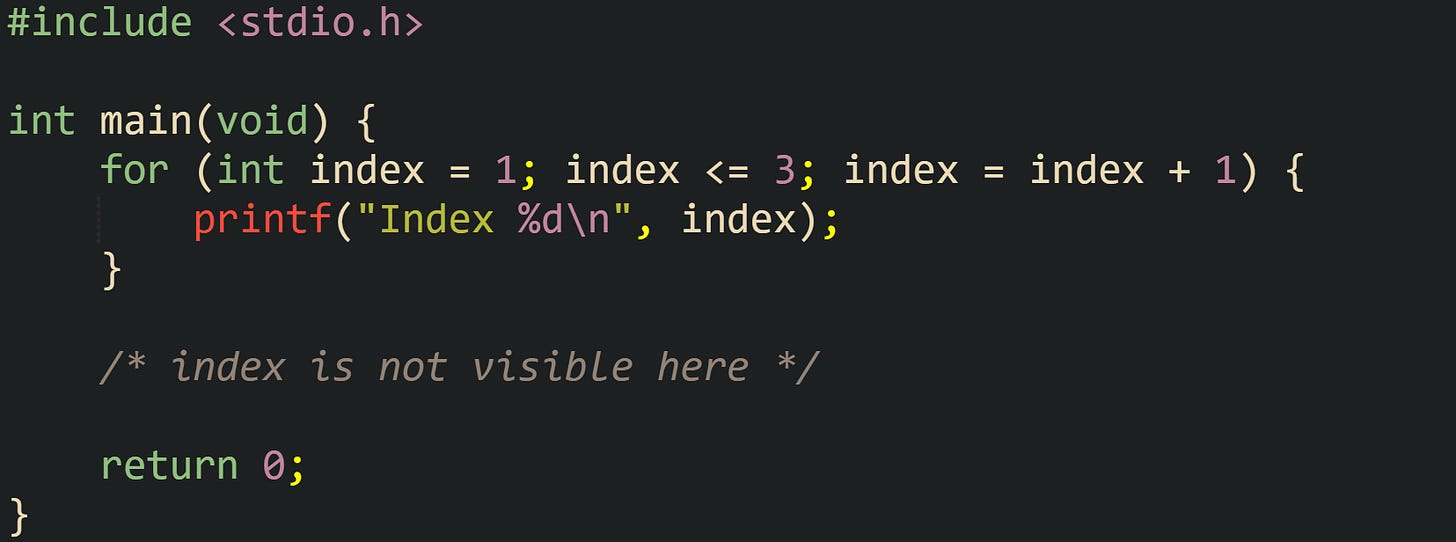

The initialization field can also declare variables that only exist inside the loop. That keeps the counter or temporary variable scoped to the loop body and the header.

Compilers that follow C99 and later standards accept declarations such as int index = 1 directly in the for header, and those variables live only from the start of the loop until the loop finishes.

In some cases the update expression does more than just increment a single variable. It can adjust several values, perform pointer arithmetic, or handle bookkeeping at the end of each pass while still keeping the overall control flow in the familiar for form. The only requirement is that the expressions in the header follow normal C syntax and that the condition field yields zero or nonzero when evaluated.

do while Loop Behavior

The do while loop form guarantees that the body runs at least once, because the condition check sits at the end instead of the beginning. Control enters the body directly, executes its statements, and then consults the condition to see if another pass should start. This structure fits cases where the body itself computes the state used in the condition.

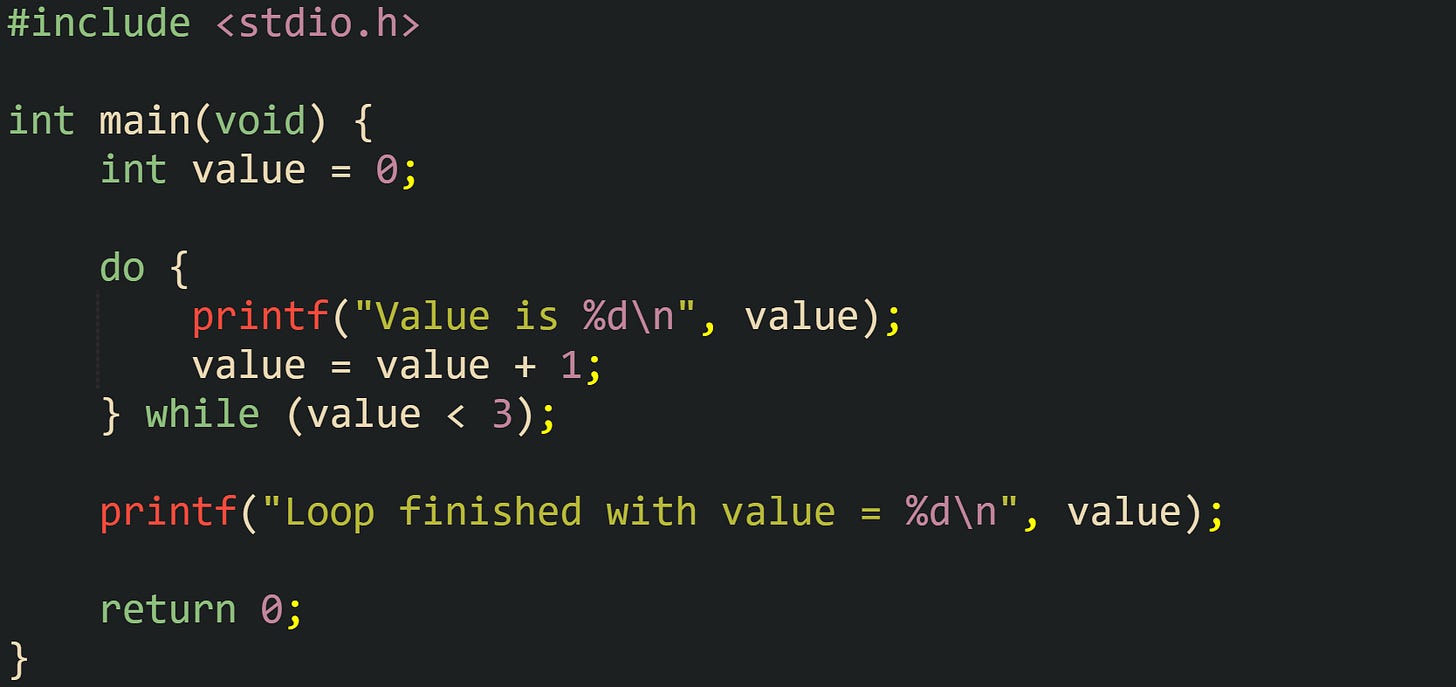

Let’s look at an example that prints values and stops at a bound:

Here, the body prints "Value is 0" before any condition check happens. After the print and increment, the condition value < 3 is evaluated. When the condition is true, control goes back to the top of the do block, and the body runs again. When value reaches 3, the condition becomes false, and execution falls through to the printf call after the loop.

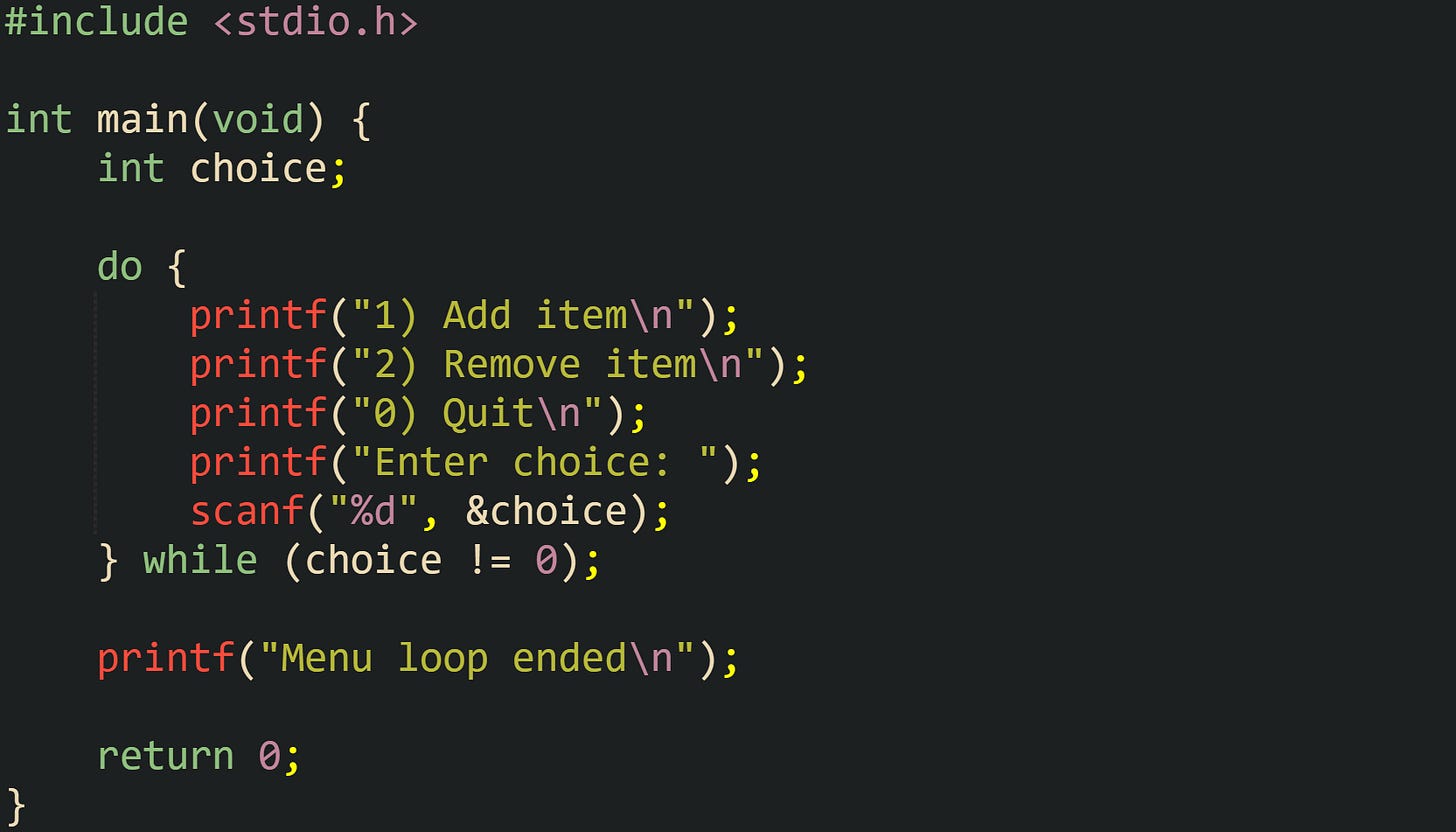

Input driven logic in C frequently uses do while so that at least one read or prompt happens before any decision to exit. A numeric menu loop uses that pattern as well:

The menu prints and reads choice once, then checks choice != 0. Valid nonzero entries send control back to the menu, while entering 0 exits the loop.

break and continue inside a do while body work in the same way as in while and for. break stops the loop immediately and transfers execution to the first statement after the loop. continue skips the remaining statements in the block for that pass and jumps directly to the condition line } while (condition); so the decision for the next pass can be made.

Something to remember with do while syntax is the semicolon after the condition. The closing part } while (value < 3); must include that semicolon, because it terminates the loop statement as a complete unit. Leaving that punctuation out leads to a compile time error rather than a different meaning.

break continue In Loops With switch

break and continue give fine control over how loops and switch statements exit or skip work. Both are tied to the nearest enclosing construct, and that rule matters when several blocks are nested inside each other.

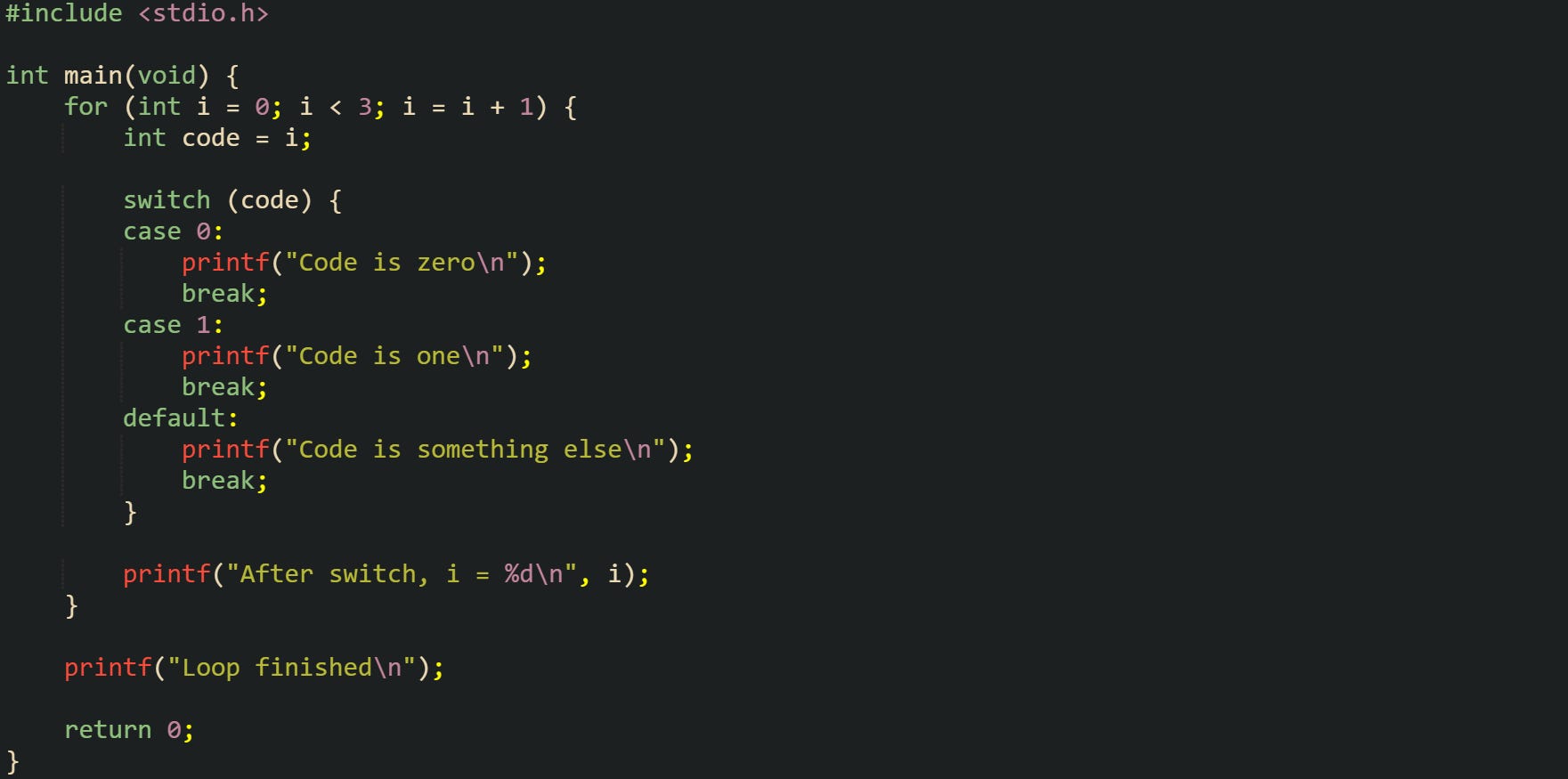

To see how break applies only to the closest surrounding construct, look at this loop that wraps a switch and watch where control goes after each case:

Each break inside the switch exits only that switch block and lands on the printf("After switch, i = %d\n", i); line. The for loop then reaches its update expression, increments i, and returns to the condition check. The switch does not end the loop unless a separate break tied to the loop runs.

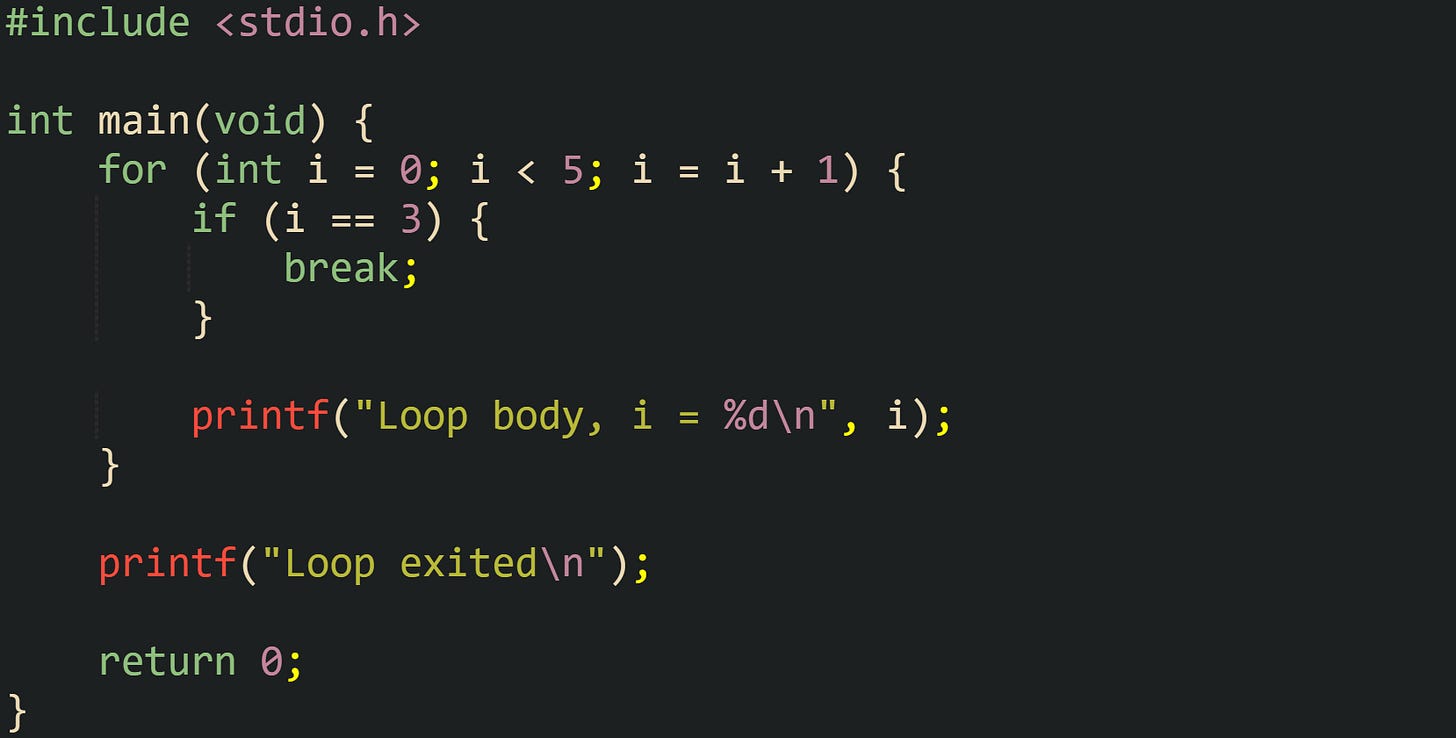

Placing a break in the loop body itself exits the loop instead of the inner switch:

The loop prints values for i equal to 0, 1, and 2. When i reaches 3, the if condition is true, the break runs, and execution jumps directly to printf("Loop exited\n"); after the loop.

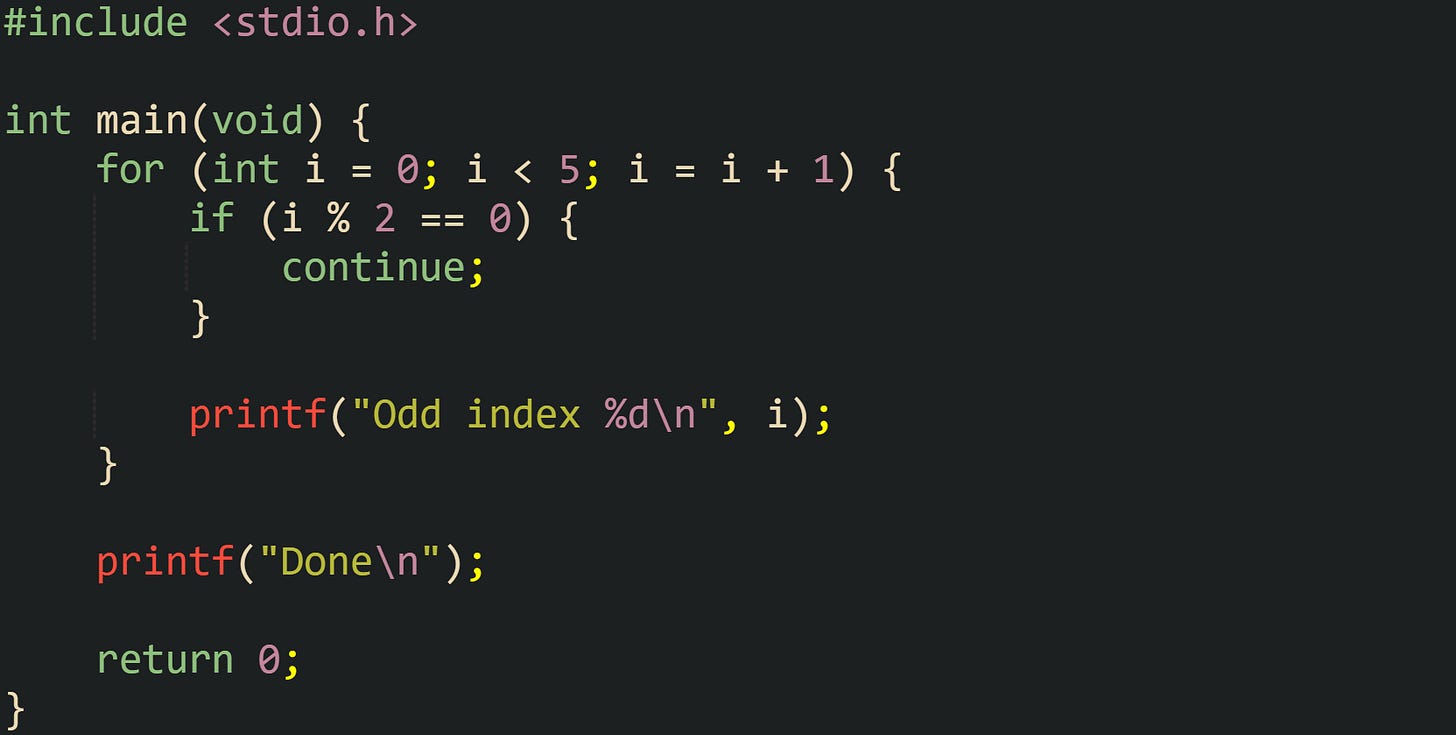

continue applies only to loops and never to a switch on its own. When a switch sits inside a loop, any continue inside that loop, including inside the switch body, skips the remaining statements in the current iteration and jumps to the loop update step and condition check. No switch that is outside any loop can contain a continue statement at all.

In this, the run skips printing when i is even, because continue causes the loop to jump to the update step without reaching the printf call. When i is odd, the if body is skipped, and the print statement runs as usual.

break in nested loops always refers to the innermost loop that surrounds it. Exiting from multiple nested loops with a single statement requires other constructs such as additional conditions, return statements, or goto, because the language does not let a single break skip several levels of nesting at once.

Conclusion

Control flow in C comes from a small set of decisions and loops that guide which statements run next. Conditions in if chains and switch blocks turn expressions into branches, with zero and nonzero values steering execution along different paths. Loop forms built from while, for, and do while keep work repeating only while their tests say so, while break, continue, and switch fall through adjust that path when special cases need earlier exits or extra shared work. With all that in mind, reading real C code becomes a matter of tracing conditions, jumps, and repetitions instead of treating control flow as something opaque.