File handling in C flows through the standard I/O library, which wraps low level operating system calls in a buffered interface that works with streams instead of raw file descriptors. The <stdio.h> header provides functions such as fopen, fclose, fread, fwrite, fprintf, and fscanf, and these operate on a FILE object that tracks buffer contents, current position, and error flags.

How stdio Represents File Streams

The stdio layer treats a file as a stream of bytes that flows between your code and the operating system. Instead of calling low level system functions for every byte, the library collects data in memory buffers and sends or receives larger chunks at once. In stdio, the stream is represented by a FILE object, and that object keeps track of where the next byte comes from or goes to, how much of the buffer is filled, and records any error or end of file condition.

FILE Objects With Operating System Handles

A FILE object is declared in <stdio.h> as an opaque type. Application code works through a pointer to this object and never sees its internal fields directly, but the library fills that structure with several pieces of state. Common fields in an implementation include an operating system handle or file descriptor, a pointer to a buffer in memory, the size of that buffer, flags that record read or write mode, and status bits for error and end of file conditions.

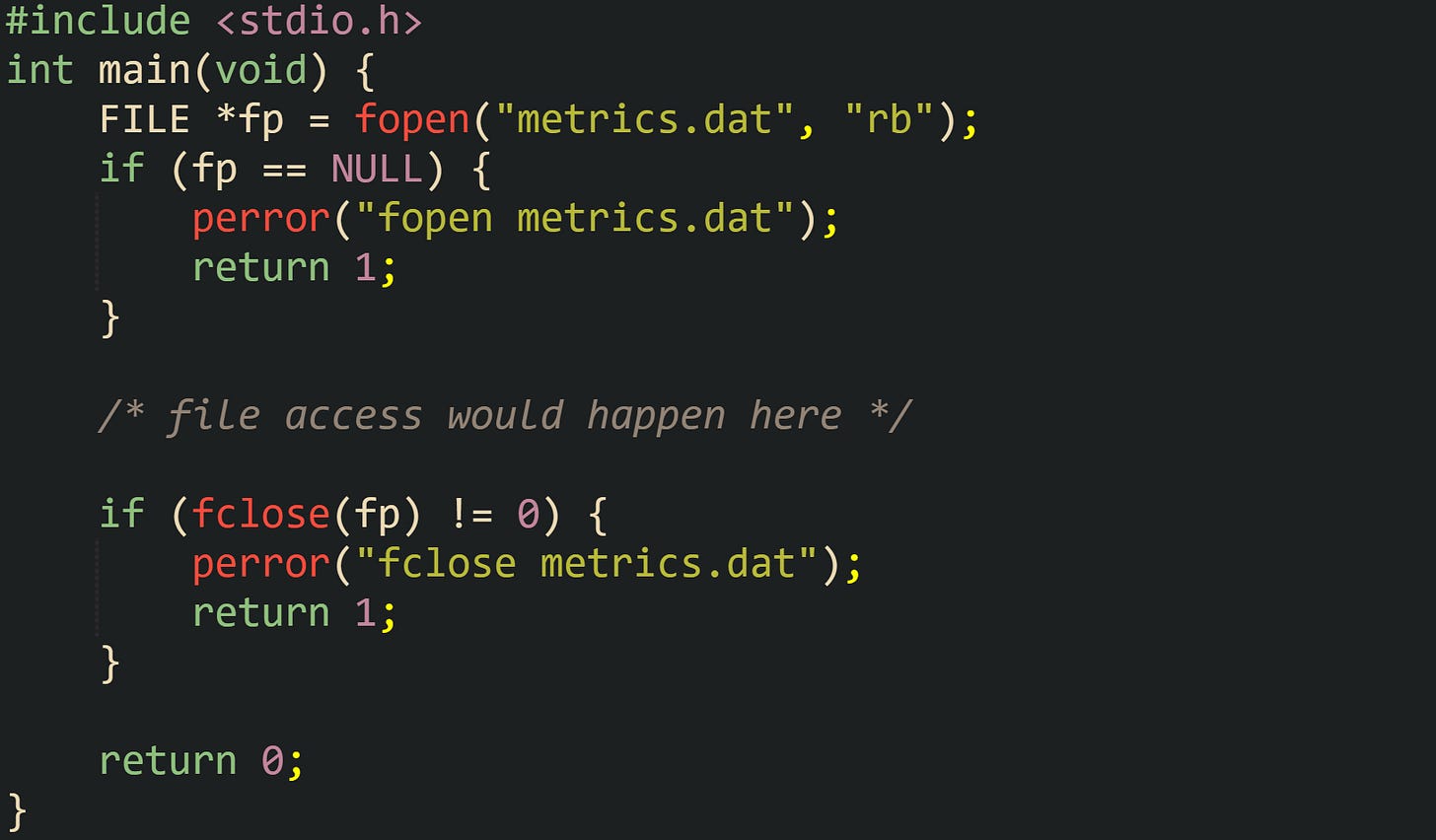

The usual entry point for creating a stream is fopen. That call asks the operating system to open a file, then associates the resulting handle with a new FILE object. A basic pattern looks like this:

This code already shows several important aspects of FILE. The pointer fp refers to a structure managed by the stdio library. fopen creates a stream, associates it with the opened file, and sets the stream mode according to the "rb" string. Buffering and other internal state are handled by the C library implementation. fclose closes the stream, flushing buffered output when the stream is writable, then releases the stream resources and closes the associated operating system handle.

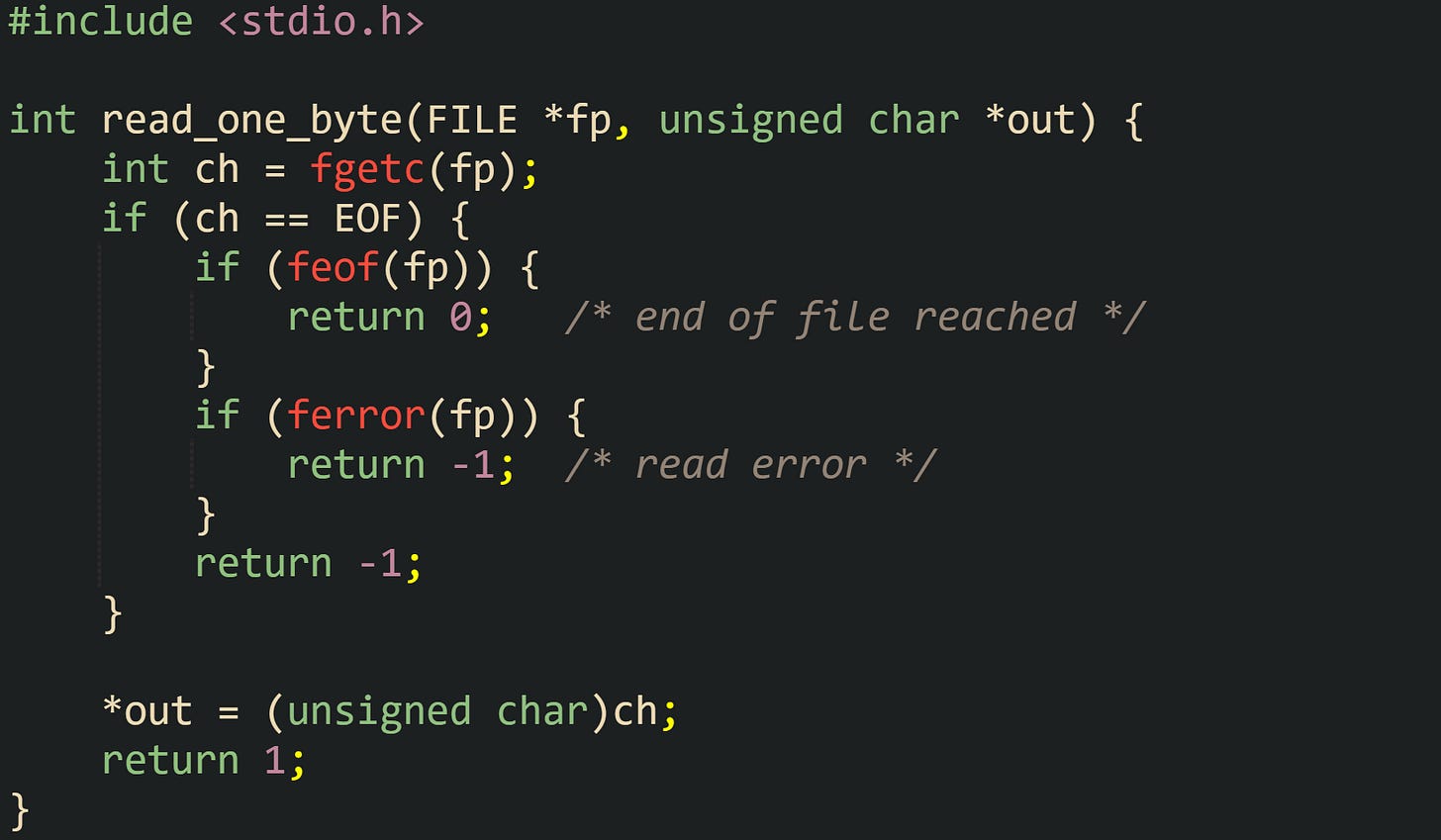

Streams also carry status information about what has happened during I/O. Two helper functions, feof and ferror, read that status from the FILE object. clearerr resets it. Let’s look at a helper that reads a single byte:

For this example, the FILE object records end of file and error conditions so the caller does not need to interpret raw system error codes on every call. The flags remain set until clearerr runs, which lets higher level code make decisions about recovery or termination based on stream state.

Standard streams fit into the same picture. stdin, stdout, and stderr are FILE * values that refer to objects created by the C runtime before main executes. They are connected to standard input, standard output, and standard error channels provided by the environment, but from the perspective of stdio they look like any other stream. The same buffer rules and status flags apply to them, and functions such as fgetc, fputc, fread, and fwrite treat them like normal files.

Buffer Behavior In Standard I/O

Buffering is central to how stdio keeps file access efficient. Reading or writing a single byte with a system call carries overhead, so the library stores data in an in memory buffer and moves it to or from the operating system in blocks. The FILE object points at that buffer and tracks how many bytes are in it, where the next read or write should happen, and what mode applies to the stream.

Three buffering strategies are commonly seen. Full buffering means the buffer fills completely before stdio calls the operating system for a write, and read calls pull in a full buffer of data at a time. Line buffering flushes output when a newline character is written and services input line by line. Unbuffered I/O directs every call to the operating system without an intermediate buffer. Regular disk files usually use full buffering, while streams connected to a terminal tend to be line buffered on output so that a newline causes the text to appear immediately.

The library picks a default policy based on the kind of stream, but functions exist to adjust it. setvbuf lets code supply its own buffer and pick a buffering mode. Take this example that turns stdout into a fully buffered stream with a fixed buffer:

In this case stdout writes to the operating system only when the buffer fills or when fflush runs. Without the call to fflush, buffered data would still reach the destination when the buffer fills or at fclose, but an application crash before that point could leave some lines only in memory.

Read operations interact with the buffer in a similar way. When a call such as fread or fgetc needs new data, stdio first checks whether unread bytes remain in the buffer. If not, it asks the operating system to fetch another block, places that block in the buffer, then hands bytes to the caller from there. This reuse of a single buffer allows many small reads from user code without paying the cost of a system call each time.

End of file and error status tie back into the buffer logic. When the operating system reports that no more bytes are available, stdio sets the end of file flag on the FILE object. When a read or write operation fails, it sets the error flag instead. Calls such as feof and ferror read those flags without disturbing buffer contents, so code can check whether a short read means that the buffer reached the final byte of the file or that an error interrupted the transfer.

File Operations With fopen fclose And Others

With the stream model in place, file work in stdio turns into a small group of operations that open a name on disk, attach a FILE object to it, then move bytes or formatted text through that stream. fopen and fclose create and tear down the connection. fwrite and fread move raw memory blocks. fprintf and fscanf handle formatted text, turning C values into human readable strings and back into typed variables. All of these calls sit on top of the same buffered machinery described earlier, so they share behavior around buffering, errors, and end of file.

Open Or Close Files Through Stdio

Work with files in stdio starts by bringing <stdio.h> into scope and asking fopen to attach a FILE object to a path on disk. The stream stores the operating system handle, buffering mode, and status flags, while your code holds only the pointer. fopen receives the path and a mode string, then returns either a valid FILE * or NULL to report failure.

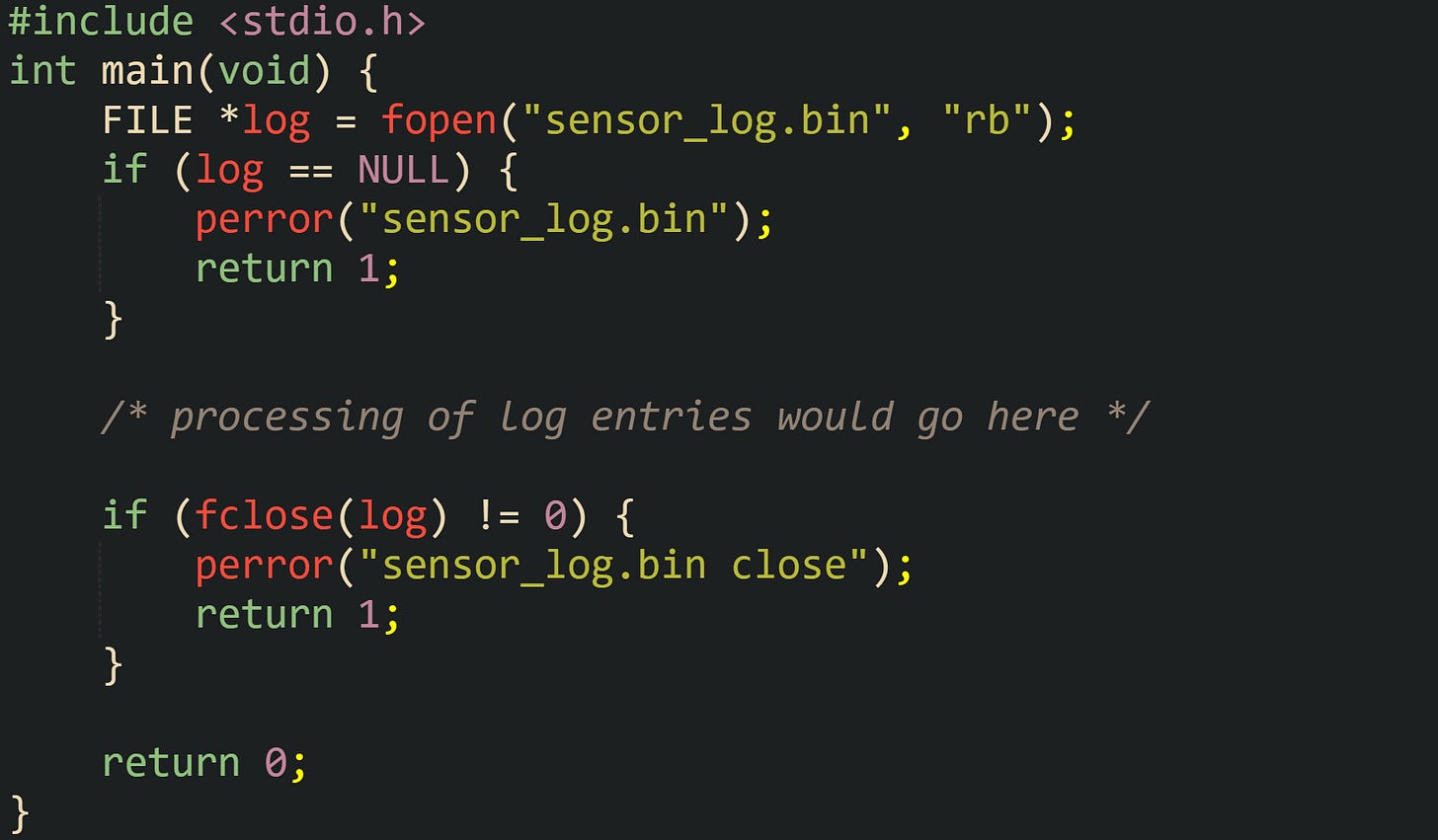

Let’s look at a example that opens a sensor log in binary read mode and checks for errors through perror, which formats the current errno value as text:

This code path shows the control flow that appears in many applications. fopen asks the operating system to open the file and, if that succeeds, allocates a FILE object, initializes its buffer, and links both pieces of state together. fclose reverses that setup by flushing buffered data if the stream is writable, closing the handle, and releasing any buffer storage tied to the stream. After fclose returns, the FILE * can no longer be used safely.

Mode strings passed to fopen control how the stream interacts with the file. "r" opens a text file for reading and fails if the file does not exist. "w" creates a new file for writing or truncates an existing file to length zero. "a" opens a file for appending so that writes go to the end, preserving existing bytes. Adding "b" requests binary mode on platforms that distinguish text and binary handling. That detail matters on Windows, where '\n' in text mode can be stored as a two byte sequence in the file, while binary mode preserves the byte stream exactly. On POSIX systems such as Linux, "b" does not change behavior, and text files are already treated as byte sequences.

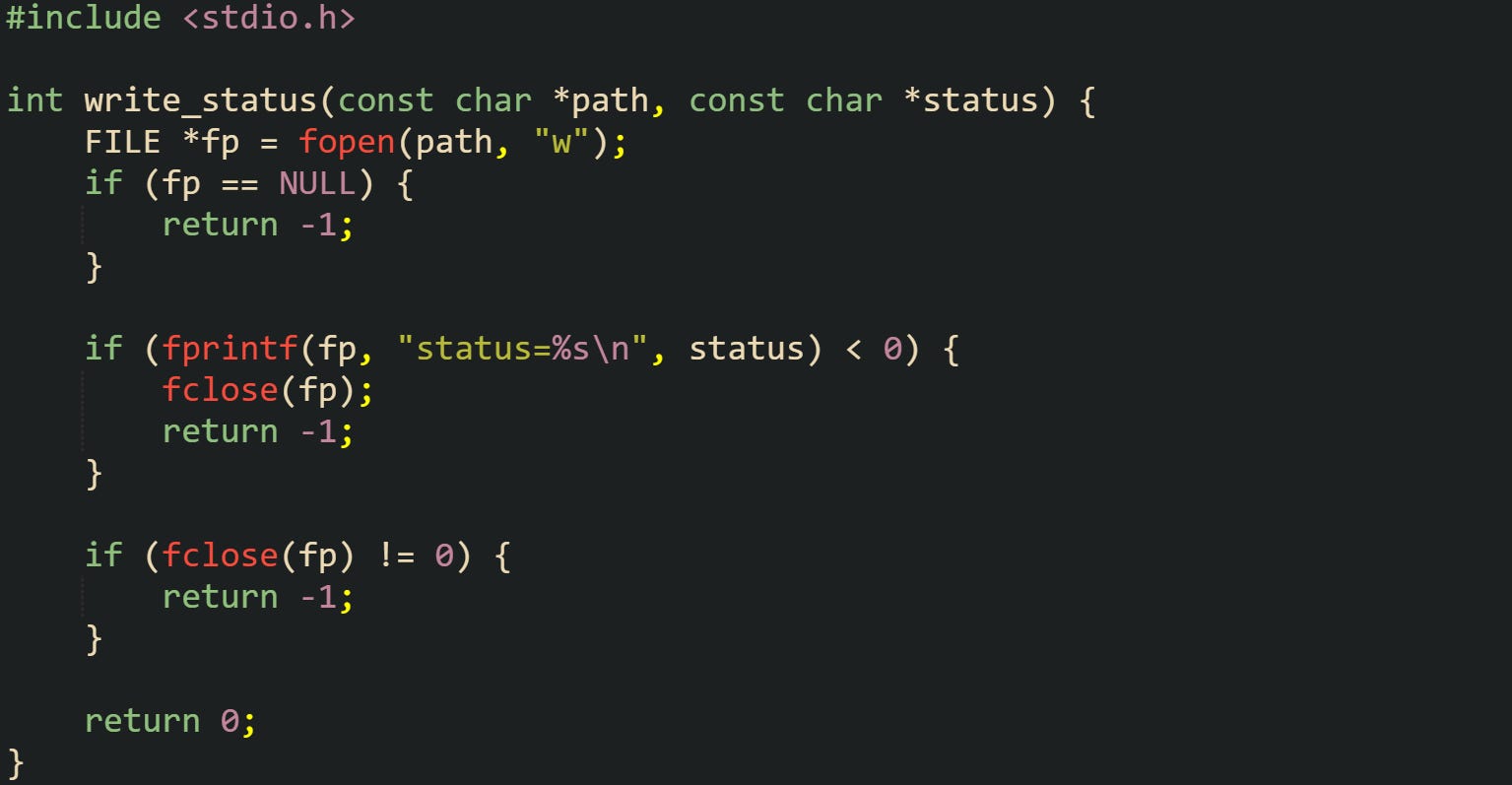

Take this example of a helper that writes a short status file and replaces it on every run, which makes the way these modes behave easy to visualize:

The "w" mode truncates any existing file named by path. The status file ends up containing only the latest status line, which is often what monitoring code needs. If appending were desired instead, changing the mode string to "a" would keep old entries and place the new one at the end. stdin, stdout, and stderr are FILE * values created before main, and freopen can redirect one of them to a file when needed.

Writing Bytes With Formatted Text Output

After a stream is open, C code can send data through it either as raw memory blocks or as formatted text. The raw path uses fwrite to copy a region of memory into the output buffer. The formatted path uses fprintf and related functions, which apply format strings similar to printf and convert C values to text in the implementation’s character encoding, such as ASCII or UTF 8.

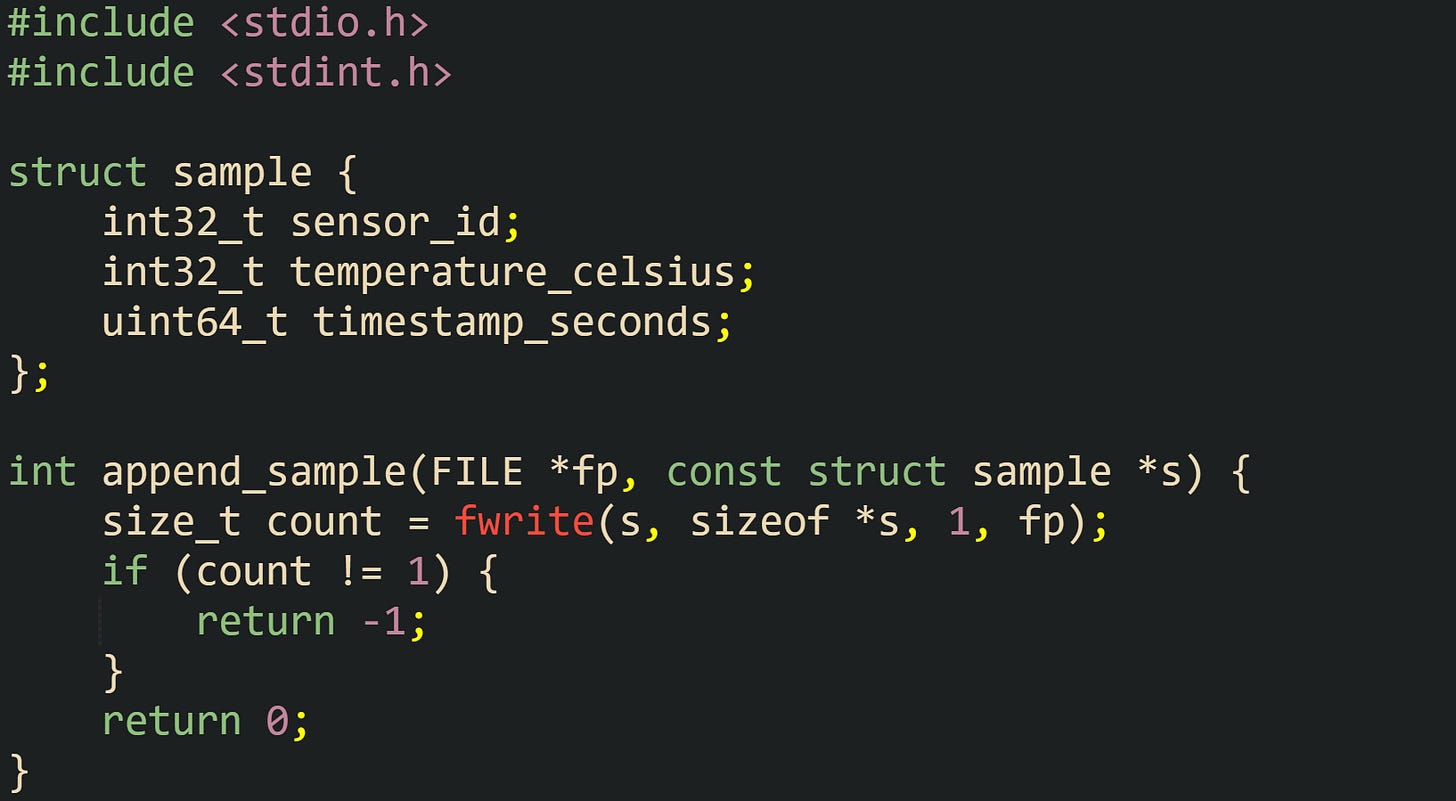

Let’s take a look at a short example that writes fixed size binary records, where the code defines a record type for temperature samples and appends a new sample to a data file:

For this code, the call to fwrite attempts to copy one object of size sizeof *s from memory into the stream. The return value indicates how many complete objects reached the buffer. When that count differs from the requested count, a write error has occurred, and the caller can inspect ferror or related indicators on the stream. Binary layouts like this depend on the platform for byte order and padding, so they work best for data read back by the same application or by another build that uses compatible structure layouts.

Formatted output with fprintf keeps the same stream concept but focuses on human readable text. It handles numeric conversion, field width, precision, and layout. Let’s consider a function that writes a plain text line for a single temperature sample:

In this, the format string %lld,%d,%d\n converts the timestamp to a long long integer in decimal form, then writes the sensor id and temperature separated by commas, followed by a newline. fprintf sends the formatted characters into the stream buffer associated with fp. When that buffer fills or when the stream is flushed, the bytes travel to the underlying operating system handle.

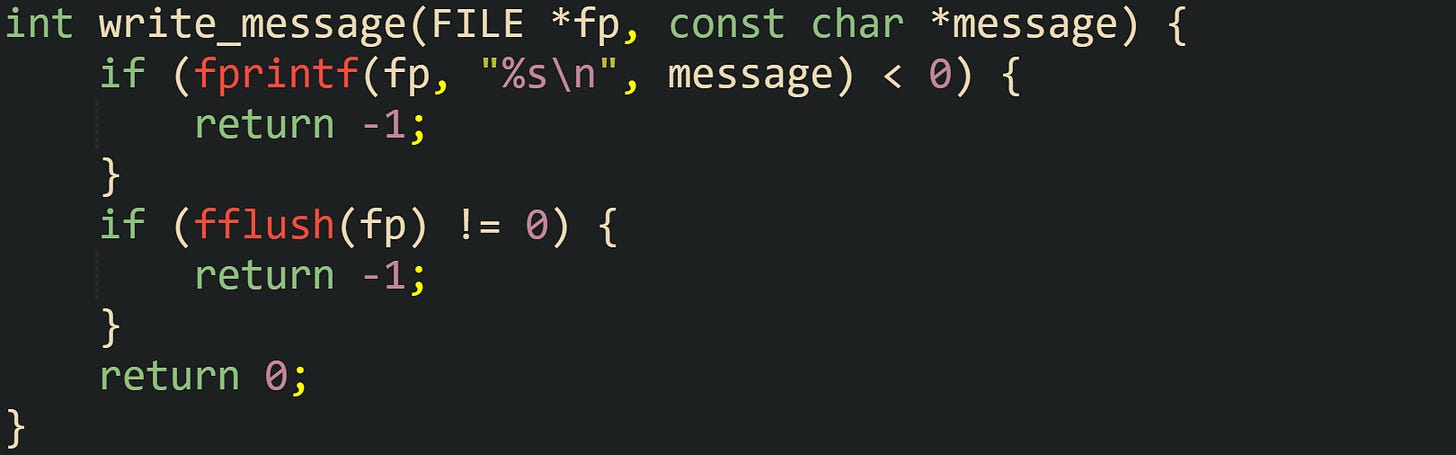

Applications that record log style messages frequently call fflush after writing an entry so that the text leaves the stdio buffer promptly and reaches the operating system file cache. This helper writes a generic log message and flushes the stream explicitly:

By calling fflush after each message, log entries spend less time sitting only in memory, so a crash is less likely to erase the most recent lines. Flushing more frequently can reduce throughput on very busy logs, so applications pick a strategy that matches their reliability and performance needs.

Reading Bytes With Structured Data

Reading data from files through stdio mirrors the ideas on the write side. fread pulls raw bytes into memory, while fscanf parses formatted text into typed variables. Both functions work with the same buffer maintained inside the FILE object, and both use the same status flags to report errors and end of file.

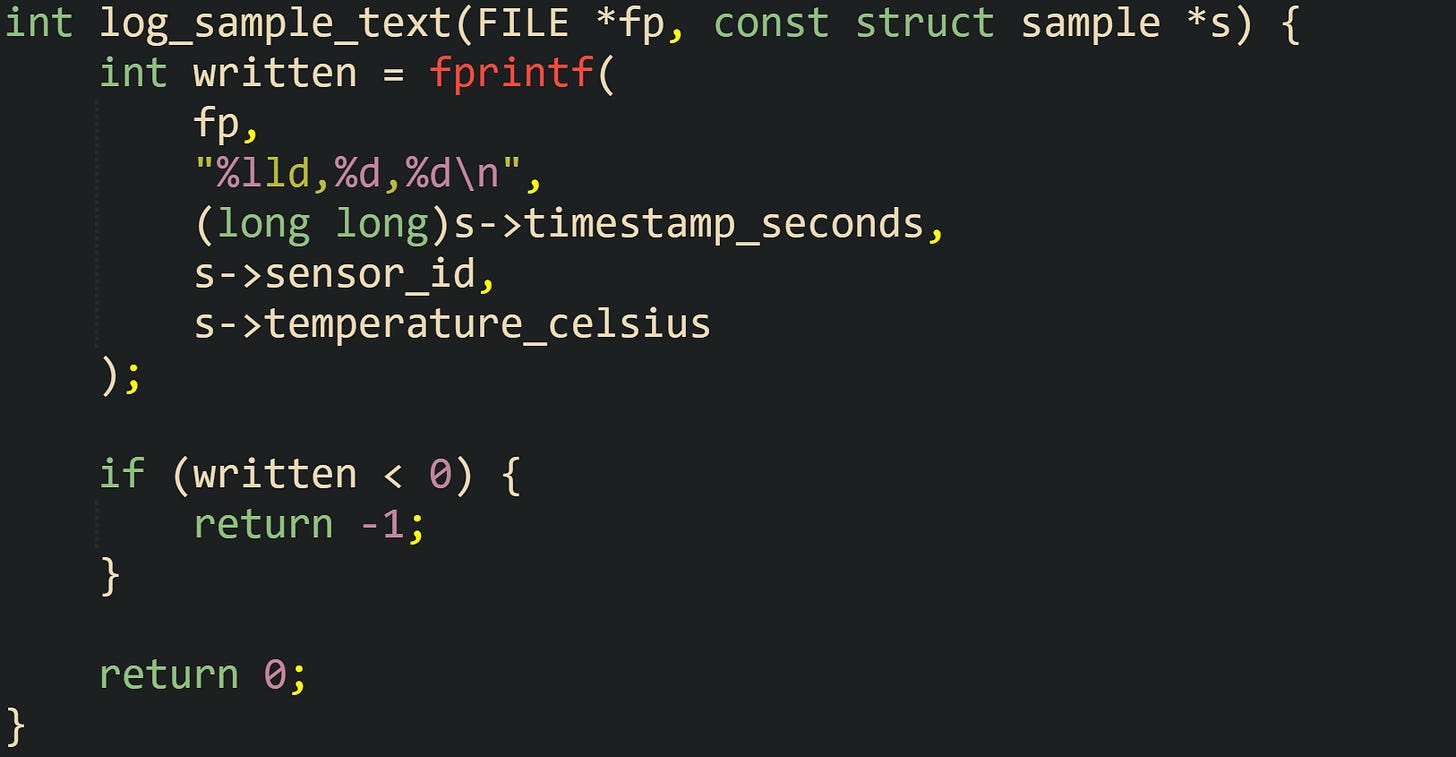

To see how fread reports success, end of file, and I/O errors, you can look at a reader for the binary sample records written earlier, and that function returns one when it fills a record, zero at end of file, and negative one on error. Like this:

fread attempts to read sizeof *s bytes into the memory pointed to by s. When the stream does not contain enough bytes to satisfy the full request, it returns a smaller count, and the FILE object marks either end of file or error state. Those status bits stay set until clearerr is called, which allows higher level code to inspect stream state after a series of reads.

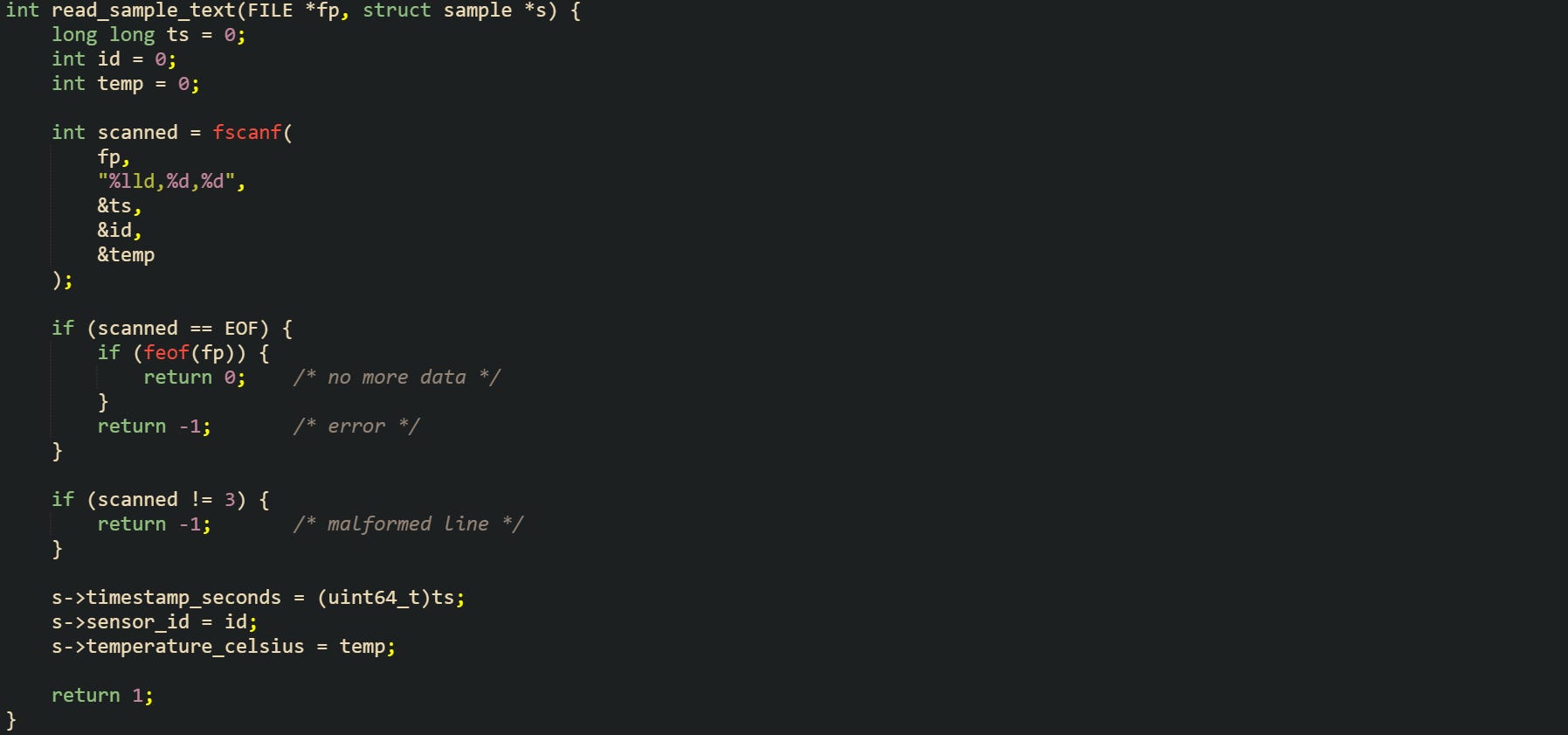

Formatted input with fscanf parses characters from the stream buffer according to a format string, converting them back into C values. The format language supports integers, floating point values, character sequences, and scansets that define which characters can appear in a field. Parsing a temperature sample stored as CSV shows how this works:

This helper reads three decimal numbers separated by commas. The count returned by fscanf tells how many fields were matched successfully. When that count is smaller than the expected number of fields and EOF is not reported, the input does not match the expected format, and higher level code may need to skip the line or log an error.

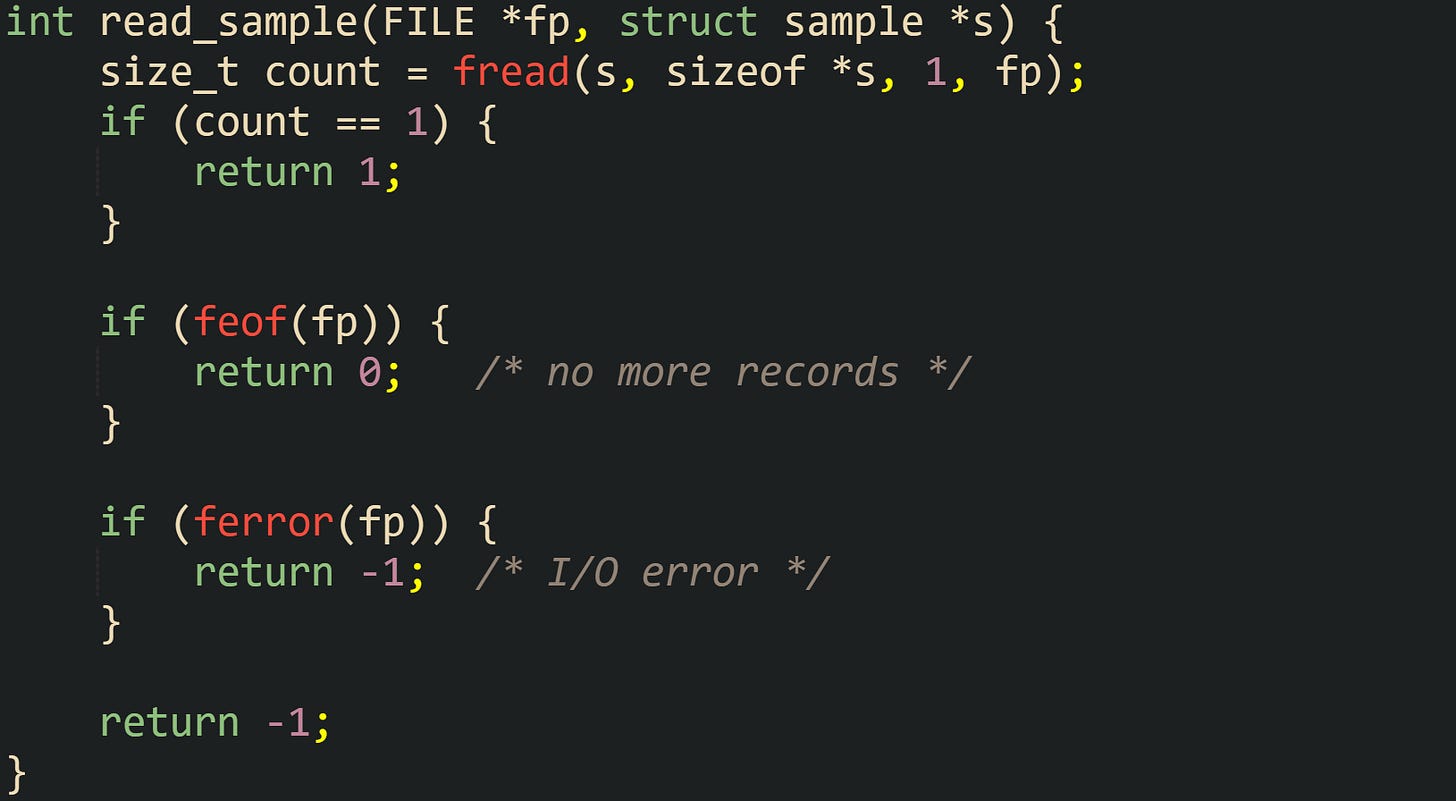

Text fields that include spaces need extra care so that parsing respects buffer boundaries. A common pattern combines a scanset conversion with a field width limit to keep text within a fixed array. The scanset tells fscanf which characters belong to the field, and the width prevents buffer overrun. Now let’s take a look at a function that reads one line from a log file where time and text appear together:

The %127[^\n] directive accepts up to 127 characters that are not newline and appends a terminating null byte, fitting safely into the text array. This style of format string keeps both the time fields and message text aligned with the storage that holds them and leaves error detection in the hands of the caller through the return value and the stream flags.

Conclusion

Viewed as a whole, file I/O with stdio comes down to streams managed by FILE objects, buffers in memory, and a small group of calls that move data between your code and the operating system. fopen and fclose create and release the stream connection, fread and fwrite handle raw byte blocks, and fprintf and fscanf work with formatted text mapped to C variables. When those pieces are familiar, it becomes easier to tell when data is still sitting in a buffer, when it has reached disk, and how to check for end of file or error flags on a stream. Log files, binary record files, and structured text files all grow from this same model, with different layouts and conventions for the bytes that pass through a FILE object.

![#include <stdio.h> int main(void) { static char buf[4096]; if (setvbuf(stdout, buf, _IOFBF, sizeof buf) != 0) { fputs("setvbuf failed\n", stderr); return 1; } printf("First line\n"); printf("Second line\n"); if (fflush(stdout) != 0) { perror("fflush"); return 1; } return 0; } #include <stdio.h> int main(void) { static char buf[4096]; if (setvbuf(stdout, buf, _IOFBF, sizeof buf) != 0) { fputs("setvbuf failed\n", stderr); return 1; } printf("First line\n"); printf("Second line\n"); if (fflush(stdout) != 0) { perror("fflush"); return 1; } return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!3eDo!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F591c89ef-fc11-4b4e-8da1-92b6d9846508_1457x843.png)

![struct log_entry { int hour; int minute; int second; char text[128]; }; int read_log_entry(FILE *fp, struct log_entry *entry) { int scanned = fscanf( fp, "%d:%d:%d %127[^\n]\n", &entry->hour, &entry->minute, &entry->second, entry->text ); if (scanned == EOF) { if (feof(fp)) { return 0; /* end of file */ } return -1; /* read error */ } if (scanned != 4) { return -1; /* format mismatch */ } return 1; } struct log_entry { int hour; int minute; int second; char text[128]; }; int read_log_entry(FILE *fp, struct log_entry *entry) { int scanned = fscanf( fp, "%d:%d:%d %127[^\n]\n", &entry->hour, &entry->minute, &entry->second, entry->text ); if (scanned == EOF) { if (feof(fp)) { return 0; /* end of file */ } return -1; /* read error */ } if (scanned != 4) { return -1; /* format mismatch */ } return 1; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!scaa!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F660fc58b-441b-4f81-a572-62e11238606e_1782x840.png)