Most C projects outgrow a single source file pretty fast, so header files and separate compilation end up in daily use. Header files hold declarations for functions, types, and global variables, while source files hold the executable code and the actual storage that the linker combines into the final binary. The compiler treats each source file with its included headers as a separate translation unit, and the linker matches declarations with their definitions so calls and references across files resolve to the right places. That arrangement lets a project grow in size without turning into one giant .c file that tries to carry every feature at once.

How Header Files Describe Interfaces

Header files give a project a shared language for talking about functions, types, and shared data without pulling in every line of implementation code. A .h file tells the compiler which pieces of an interface exist and how they look from the caller’s side, while the matching .c file holds the bodies and storage that actually run. When many source files all include the same header, they agree on the same types and function signatures, so calls across translation units stay consistent.

Typical Contents Of A Header File

In C, header files are ordinary text files with a .h extension that the preprocessor drops into a source file whenever it sees #include "name.h". There is no separate compilation step for headers and no special binary representation. The value comes from the declarations placed in them and the way those declarations are reused across source files.

Most headers carry a small group of interface pieces in one place. Functions appear as declarations with full parameter lists so that calls get checked for argument count and types. Types appear as struct, enum, and typedef declarations so that every translation unit agrees on field order and sizes. Macro constants set shared numeric values or flag bits that many source files need. extern declarations announce global variables that will live in one .c file. In C99 and later, many projects also keep short static inline helpers in headers so common logic for tiny helpers stays close to the interface.

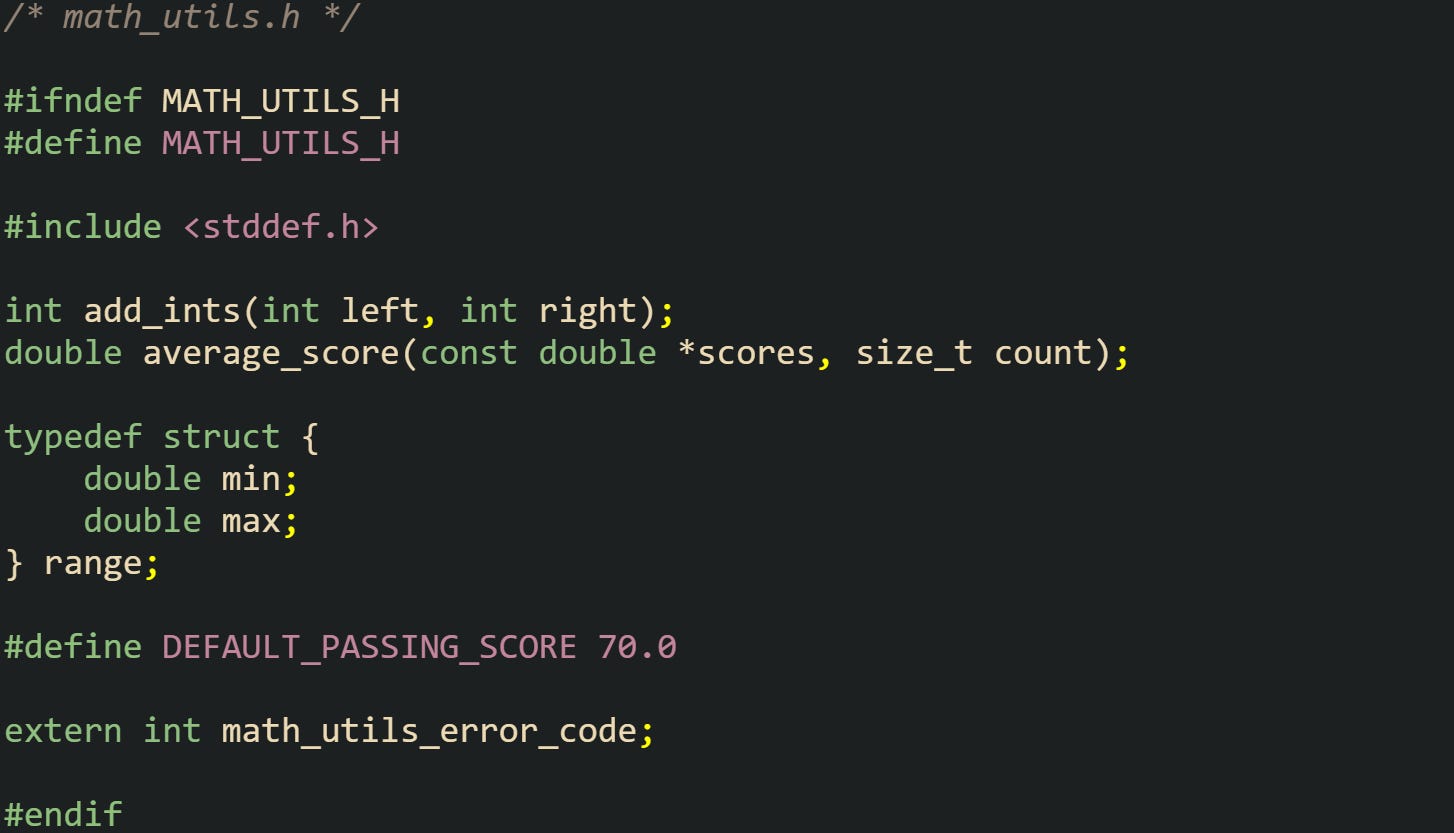

Take this math utility header that pulls these pieces into one place in a way that stays easy to read:

This header tells the compiler that any translation unit including math_utils.h can call add_ints and average_score, use the range struct with the exact layout shown, rely on the DEFAULT_PASSING_SCORE macro value, and refer to math_utils_error_code as a global integer that will be defined in one source file.

The matching .c file carries the function bodies and the single definition of the global variable:

Any .c file that includes the header can call add_ints and average_score and read or write math_utils_error_code without seeing these bodies, because the compiler only needs the declarations from the header to type check the calls and references, while the linker later connects those calls to the bodies in math_utils.c.

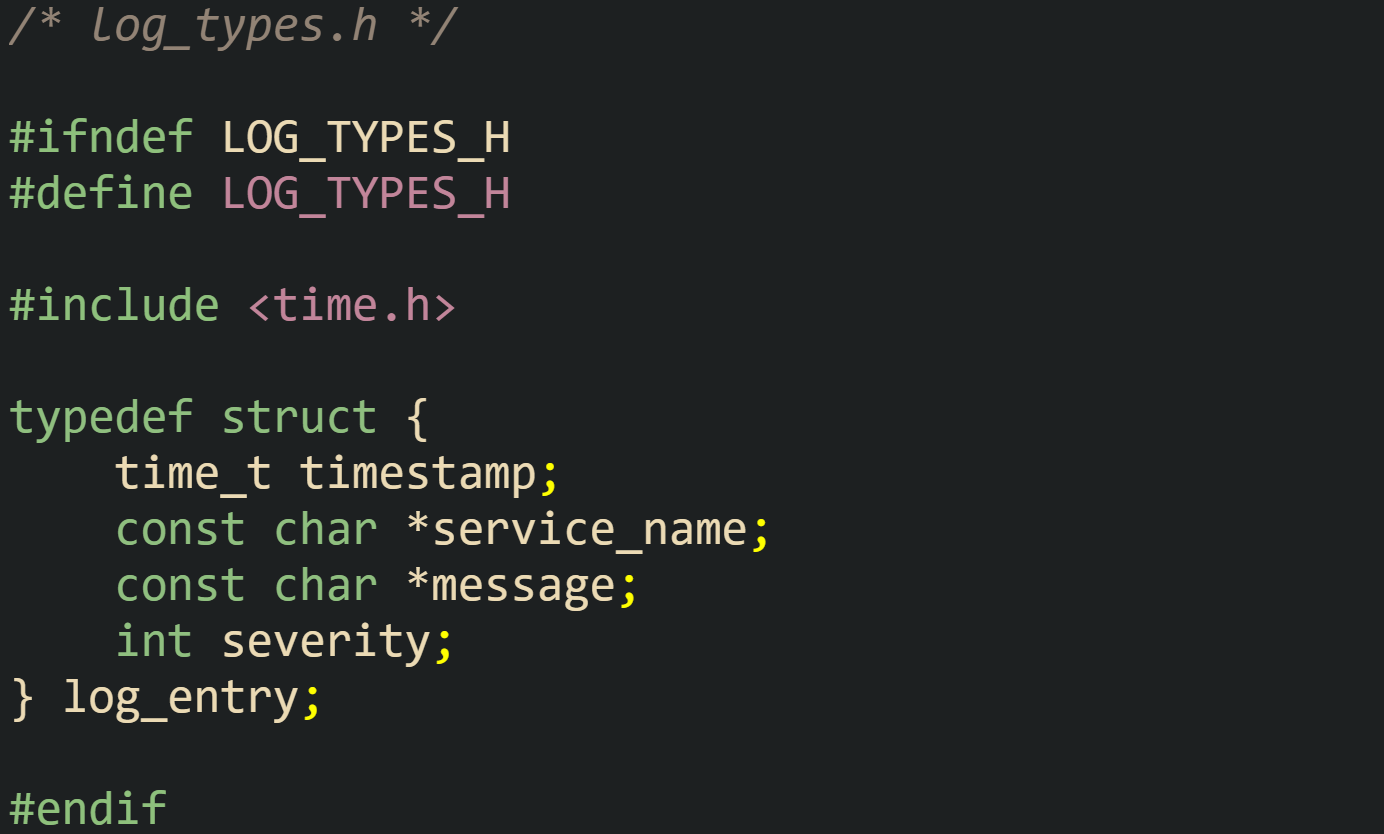

Headers also carry shared type definitions so that data structures match across the project. A log module, for instance, can pass around a struct that represents a log entry coming from a service in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, and other modules can read that struct without guessing at the layout.

Every translation unit that includes log_types.h sees the same log_entry layout, so a pointer to log_entry passed from one module to another always refers to the same sequence of fields in memory. That shared view lets a logger module allocate an array of log_entry values and send pointers to a formatter or file writer without disagreements about field order.

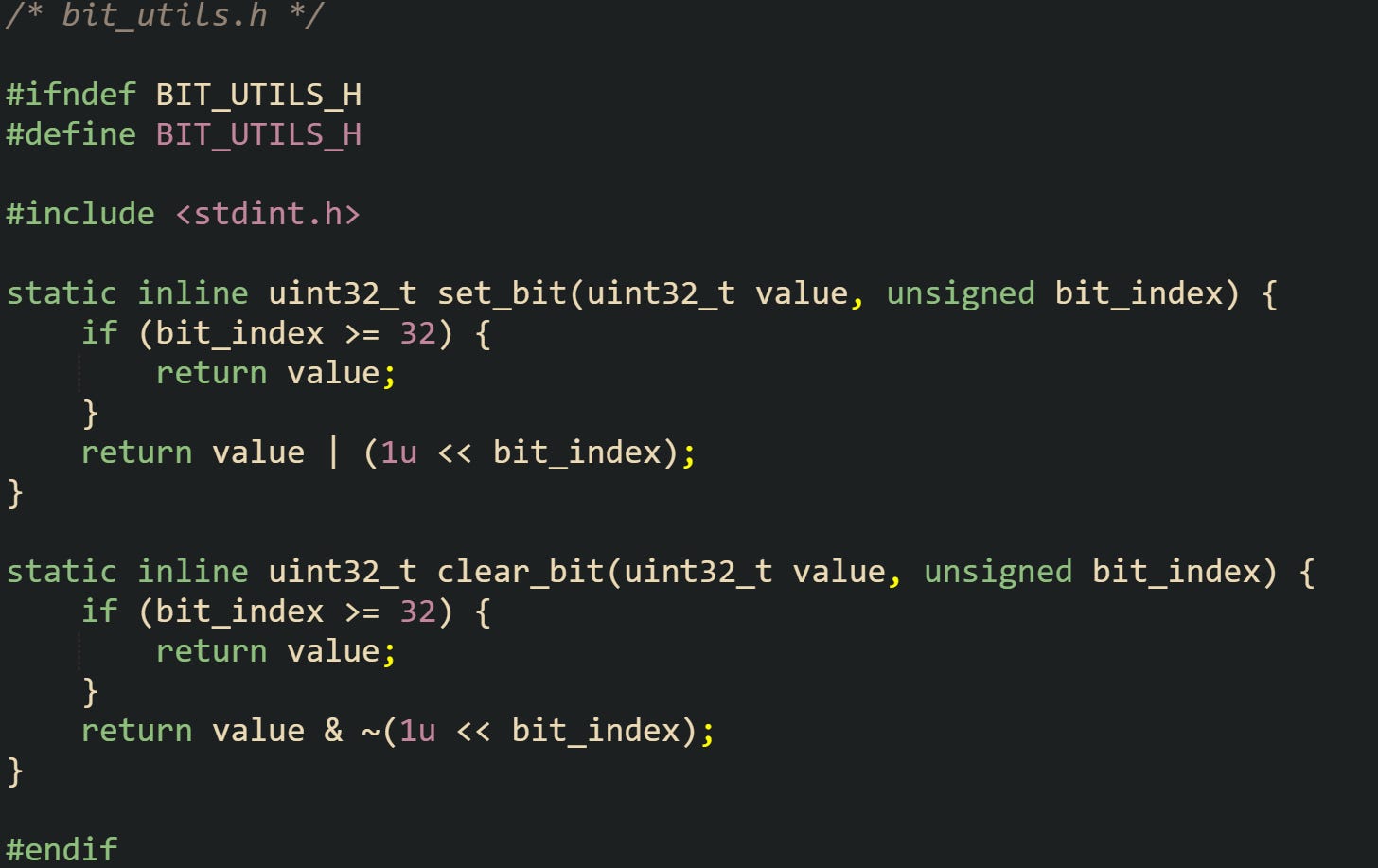

Some headers also provide small static inline helpers where the cost of a function call would be higher than the work being done. Bit utility headers show up frequently in low level code:

Every translation unit that includes this header gets its own private copies of set_bit and clear_bit because they are static, so the linker never sees multiple external definitions with the same name. The inline keyword gives the compiler freedom to fold the bodies into call sites when that matches its optimization strategy.

Include Guards In Modern Compilers

Real projects rely on many headers, and those headers pull in other headers. Chains of includes build up a tree that can pass through the same file more than once in a single translation unit. If the same header body were processed twice without protection, the compiler could encounter repeated type declarations, repeated macro definitions, or repeated function definitions from that file, which leads to errors.

Include guards prevent that problem by forcing the preprocessor to act on the body of a header only once per translation unit. The usual pattern uses a macro that marks the header as already processed.

The first time network_client.h is included in a translation unit, NETWORK_CLIENT_H is not defined, so the body between #define NETWORK_CLIENT_H and #endif is kept and the macro NETWORK_CLIENT_H becomes defined. Later includes of the same file in that translation unit see that NETWORK_CLIENT_H is already defined, so the preprocessor discards the entire guarded region. That behavior keeps type and function declarations from being seen twice.

Include guards also help when two different headers include each other indirectly. Suppose user_service.h includes network_client.h, while network_client.h includes a shared user_service_types.h header. Include guards on all three files avoid recursive inclusion problems by discarding second and later passes through the same header body.

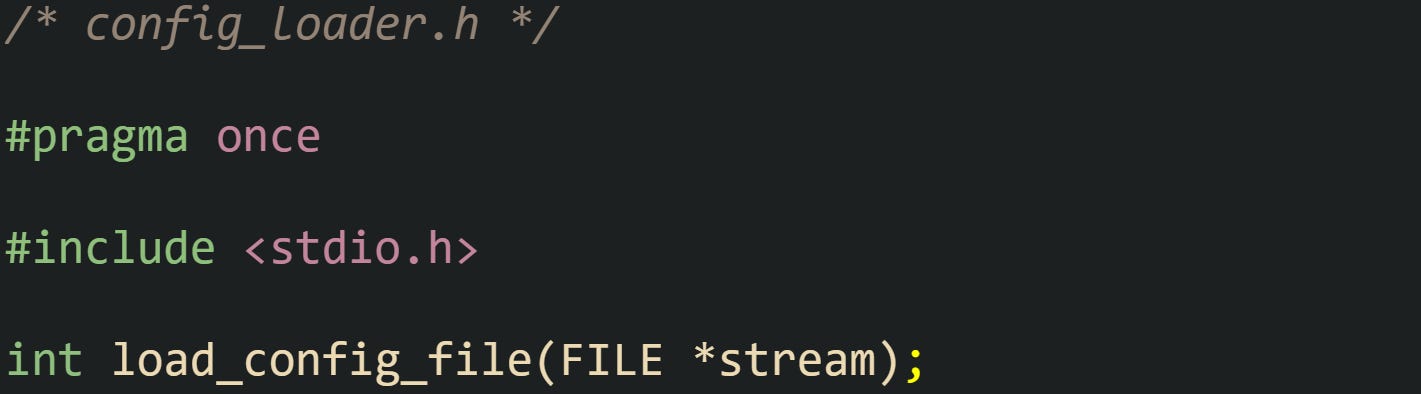

Many modern compilers also accept #pragma once at the top of a header file:

Compilers that honor this directive remember that config_loader.h has already been included in the current translation unit and skip further processing of that file. Plenty of projects keep both #pragma once and traditional include guards around their headers, so compilers that understand the pragma can take advantage of it, while compilers that do not still rely on the guard macro.

How Separate Compilation Connects Source Files

Separate compilation in C lets you break an application into many .c files that are built on their own, then stitched into one executable by the linker. Each source file, plus the headers it includes, turns into one translation unit. The compiler only needs to see declarations inside that translation unit to type check calls and references, and it records which symbols are defined there and which ones are only referenced. The linker later walks across all those compiled units and matches references to definitions so calls to functions and accesses to global variables go to the right places.

This split gives C code a clear boundary between what the compiler checks locally and what the linker connects across the whole build. Declarations in headers make sure many translation units agree on the same function signatures and data layouts, while definitions in .c files carry the real bodies and storage that eventually live in the executable or shared library.

Declarations Versus Definitions In Practice

Separate compilation revolves around a basic rule in C that often gets repeated in textbooks, but it becomes much clearer when you watch it play out in code. The declaration tells the compiler that something exists with a given type and name, while a definition actually allocates storage for an object or provides a body for a function. Declarations can appear in many translation units, but there must be exactly one definition with external linkage for each function or global variable across the whole executable.

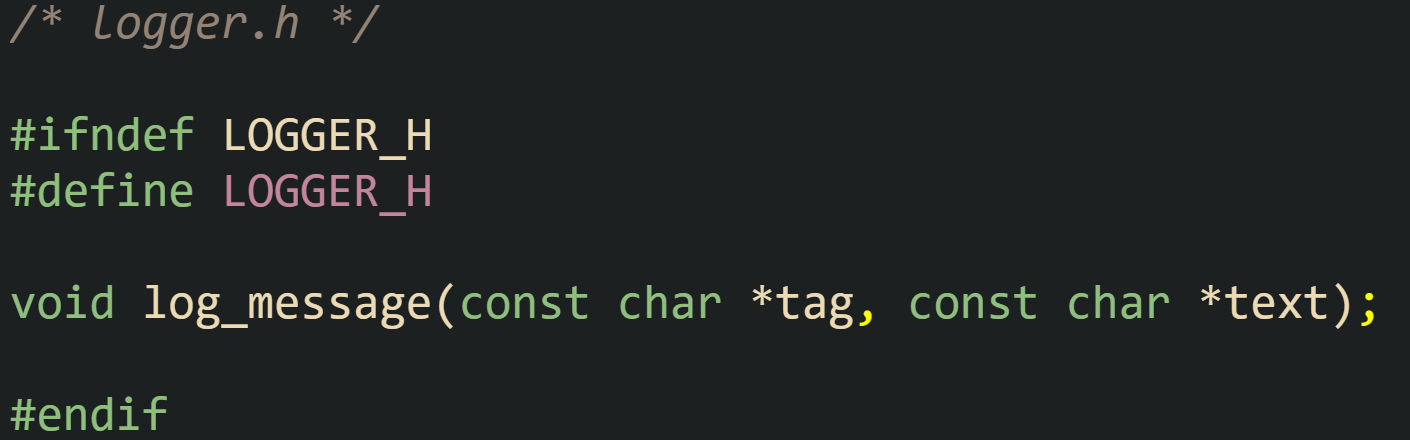

Let’s look at a logger module that gives a better visual of the split. One header states the interface.

The compiler that reads this header now knows that a function named log_message exists somewhere, takes two const char * arguments, and returns void. No body appears here, so this is only a declaration.

The implementation file holds the definition:

In logger.c, the function declaration in logger.h appears again when the header is included, but now there is also a body. This combination counts as the definition that the linker expects to find exactly once.

And client code can then call the logger like:

Compilation of main.c only needs logger.h. The compiler reads the declaration, checks the calls, and records that main.c refers to a symbol named log_message that is not defined in that translation unit. Later, when the linker sees object files from main.c and logger.c, it connects the reference in main.o to the definition in logger.o.

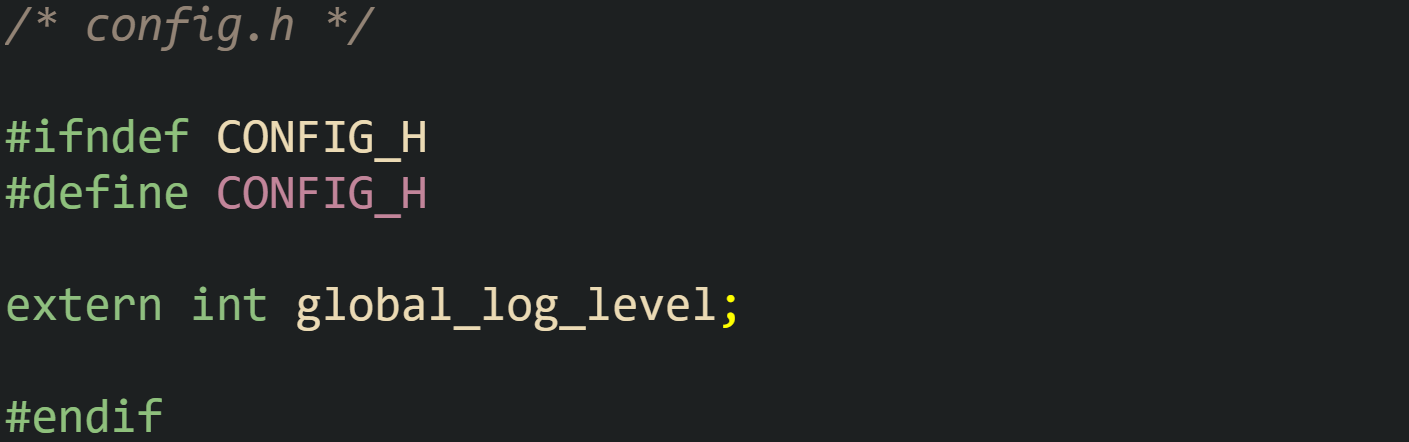

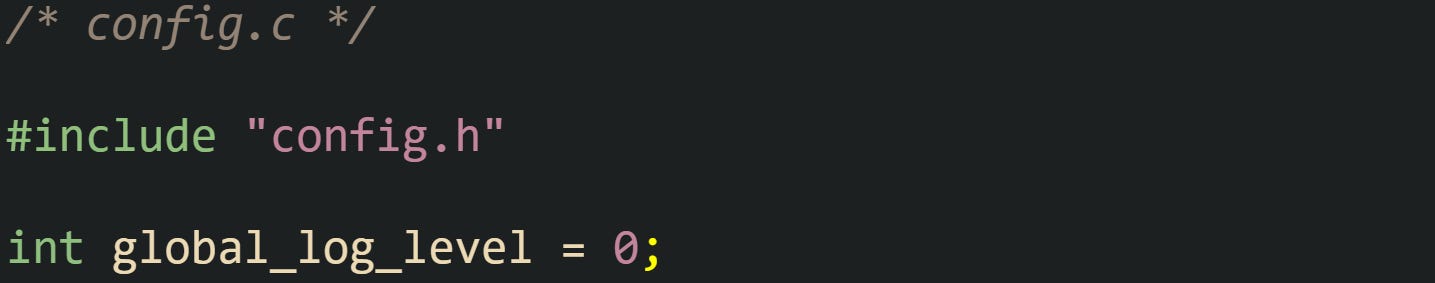

Global variables follow the same pattern. One header can announce that a global exists, and one .c file can provide the storage:

The extern keyword tells the compiler that global_log_level exists, but does not define storage for it in this translation unit. Storage appears in exactly one source file:

Any translation unit that includes config.h can read or write global_log_level. The compiler records references in those units, and the linker matches them to the single definition in config.o.

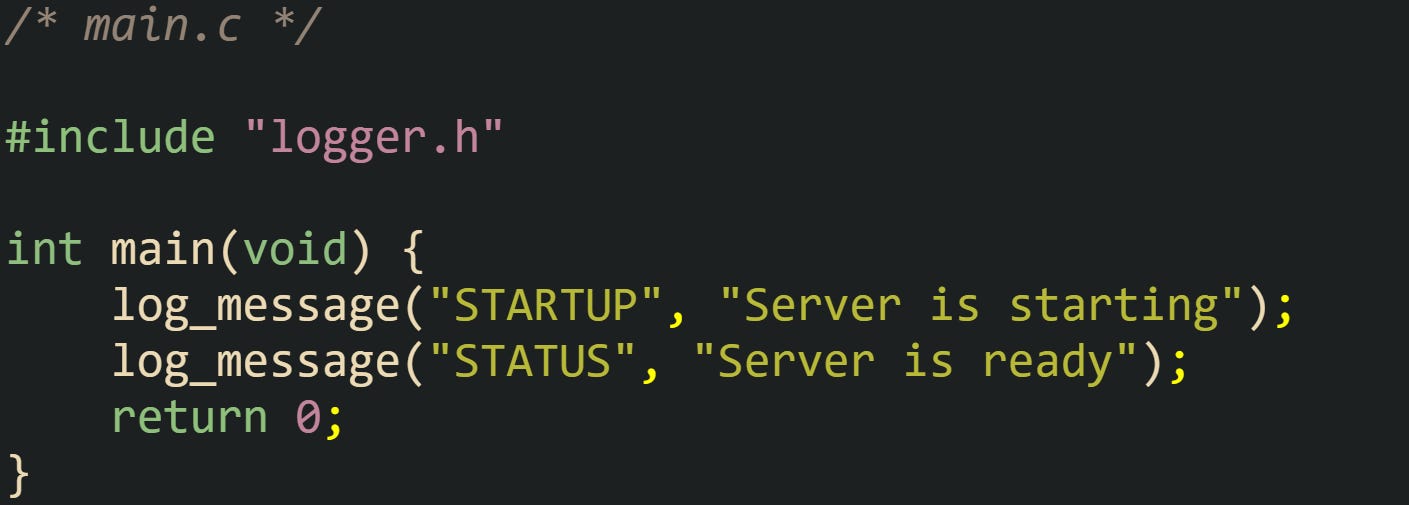

Trouble starts when a definition sneaks into a header with external linkage. Let’s say someone writes this version of the logger header:

Every translation unit that includes bad_logger.h now gets a full definition of log_message. The compiler accepts each translation unit on its own, but the linker later sees multiple external definitions of the same symbol and reports an error about duplicates. Good practice is to keep function bodies with external linkage in .c files and reserve headers for declarations and static inline helpers.

How The Compiler Handles Translation Units

For the compiler, separate compilation starts with the preprocessor. The preprocessor reads a .c file, expands macros, and replaces #include lines with the contents of the target header files. After this pass, the compiler sees one combined source stream that contains the original .c code plus all the header text pulled in through includes. That combined source is one translation unit.

The compiler then parses declarations, statements, and expressions in that translation unit. Every function has to be declared before it is used, so the compiler can check calls and create the right symbol records. Every global with external linkage has to be declared before it is referenced, so the compiler can record its type and add symbol table entries for it.

Two broad groups of symbols end up in the object file. Some are defined there, such as functions with bodies or global variables with storage. Others are only referenced, with no storage or body in that translation unit. The object file records both the symbols that are defined and the symbols that are referenced, along with types and relocation information.

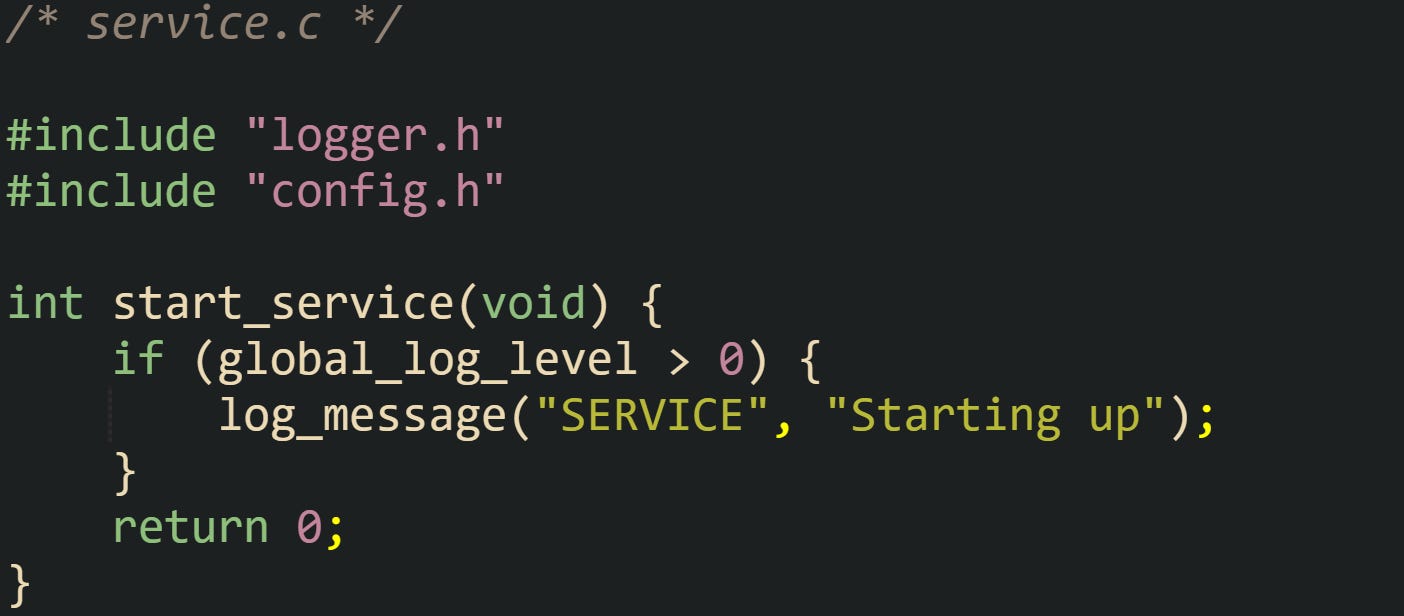

To make this easier to follow, think about a small translation unit that uses both the logger interface and a configuration interface:

From the perspective of the compiler, start_service is defined here, while log_message and global_log_level are external symbols that are only referenced. The compiler writes machine code for start_service, plus relocation records that say where the address of log_message and the address of global_log_level need to be filled in later. It does not need the bodies for log_message or the actual storage for global_log_level to complete this translation unit.

C standards like C11, C17, and C23 keep this same translation unit model. Newer language features influence what appears in headers and how types and attributes are written, but the idea that the compiler works file by file, guided by headers, remains steady.

How The Linker Connects Object Files

Object files produced by the compiler contain machine code, data, symbol tables, and relocation entries. Separate compilation leaves the last step of connecting all those units to the linker, which sees the project as a whole. The linker reads all object files and any static or shared libraries named on its command line and then resolves references across them.

Symbol tables inside object files mark some names as defined and some as undefined. Definitions belong to functions or objects. Undefined entries belong to references that need to be matched with definitions elsewhere. Relocation entries point at machine code locations or data locations that depend on final addresses of symbols. The linker walks those structures, combining code and data into large sections and patching all references so they point to the correct addresses.

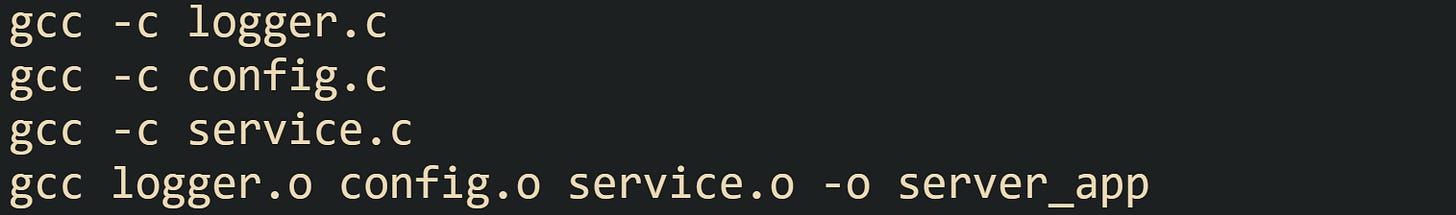

Let’s look at a typical build with separate compilation that involves commands of this style:

The first three commands compile each translation unit into an object file. The final command invokes the linker through gcc, feeding it the object files. logger.o provides a definition for log_message, config.o provides a definition for global_log_level, and service.o holds references to both. During linking, undefined references in service.o are matched to definitions in the other object files.

Two common classes of linker errors trace back to how separate compilation is set up. Multiple definition errors appear when more than one object file defines the same external symbol, which usually happens when a function body or global variable definition is placed in a header instead of in a single .c file. Undefined reference errors appear when declarations exist in headers and references appear in source files, but no object file actually defines the symbol named there, perhaps because the corresponding .c file was left out of the build command.

Static libraries fit into the same model. A static library is a collection of object files stored in one archive file, such as libmathutils.a or mathutils.lib. During linking, the linker pulls in object files from the library only when they provide definitions for symbols that are needed. Headers for such a library still carry declarations for the public functions and types. Client code includes those headers, and the linker consults the library archive when it tries to satisfy undefined symbols from the client object files.

Shared libraries, such as .so files on Linux or .dll files on Windows, also connect through symbol tables. Object files that refer to functions or objects in a shared library still rely on declarations in headers at compile time. Linking records that some symbols will be resolved from a shared library, and the dynamic loader finishes the job when the application starts. The separation between declarations in headers, definitions in source files, compilation into object files, and final linking through symbol tables is the same, even though the details of loading differ between static and shared libraries.

Conclusion

Header files and separate compilation turn C projects into collections of smaller translation units that cooperate through shared declarations. Headers lay out the function signatures, types, and globals that every source file agrees to, while .c files supply the bodies and storage that the compiler turns into object files. The compiler checks each translation unit on its own, records which symbols are defined or only referenced, and hands that information to the linker. The linker then matches references to definitions across all object files and libraries, so calls, data access, and shared types keep working correctly as the codebase grows.

![/* math_utils.c */ #include "math_utils.h" int math_utils_error_code = 0; int add_ints(int left, int right) { return left + right; } double average_score(const double *scores, size_t count) { if (scores == NULL || count == 0) { math_utils_error_code = 1; return 0.0; } double sum = 0.0; for (size_t i = 0; i < count; i++) { sum += scores[i]; } return sum / (double)count; } /* math_utils.c */ #include "math_utils.h" int math_utils_error_code = 0; int add_ints(int left, int right) { return left + right; } double average_score(const double *scores, size_t count) { if (scores == NULL || count == 0) { math_utils_error_code = 1; return 0.0; } double sum = 0.0; for (size_t i = 0; i < count; i++) { sum += scores[i]; } return sum / (double)count; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!gh7v!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff833aa17-3a43-44ae-8837-187d692785fb_1452x926.png)

![/* network_client.h */ #ifndef NETWORK_CLIENT_H #define NETWORK_CLIENT_H #include <stddef.h> typedef struct { int socket_fd; char host[256]; unsigned short port; } network_client; int connect_client(network_client *client, const char *host, unsigned short port); int send_bytes(network_client *client, const void *buffer, size_t length); int receive_bytes(network_client *client, void *buffer, size_t length); #endif /* network_client.h */ #ifndef NETWORK_CLIENT_H #define NETWORK_CLIENT_H #include <stddef.h> typedef struct { int socket_fd; char host[256]; unsigned short port; } network_client; int connect_client(network_client *client, const char *host, unsigned short port); int send_bytes(network_client *client, const void *buffer, size_t length); int receive_bytes(network_client *client, void *buffer, size_t length); #endif](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xxKY!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3dbb6146-b9c7-4ef0-8f02-11ab1600617f_1382x627.png)

![/* logger.c */ #include <stdio.h> #include "logger.h" void log_message(const char *tag, const char *text) { fprintf(stderr, "[%s] %s\n", tag, text); } /* logger.c */ #include <stdio.h> #include "logger.h" void log_message(const char *tag, const char *text) { fprintf(stderr, "[%s] %s\n", tag, text); }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!qDp6!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F33147c63-58ea-4a1f-a974-848041413215_1419x451.png)

![/* bad_logger.h */ #ifndef BAD_LOGGER_H #define BAD_LOGGER_H #include <stdio.h> void log_message(const char *tag, const char *text) { fprintf(stderr, "[%s] %s\n", tag, text); } #endif /* bad_logger.h */ #ifndef BAD_LOGGER_H #define BAD_LOGGER_H #include <stdio.h> void log_message(const char *tag, const char *text) { fprintf(stderr, "[%s] %s\n", tag, text); } #endif](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!PxY8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F769788f5-5d98-46b2-a50a-dc0ac990a2e9_1415x666.png)