Before any C source file reaches the compiler, the C preprocessor runs first and quietly rewrites the text. It reads your source, pulls in header files, replaces macros, applies conditional compilation, and then hands a large expanded translation unit to the compiler. Learning how this stage behaves makes header files, macros, and build flags easier to deal with and explains what happens when you write #include, #define, #if, and header guards.

Preprocessor Stage Before Compilation

C translation goes through a set of stages before any actual machine code is produced, and the preprocessor sits near the front of that chain. The tool reads raw source text, normalizes some details such as line endings, strips comments, handles directives like #include and #define, expands macros, applies conditional compilation, and only then passes a single expanded translation unit to the main compiler. Modern toolchains such as GCC, Clang, and MSVC still keep this separation conceptually, even when they share internal pipelines. That separation explains why preprocessor behavior can differ from what you expect if you think only in terms of C syntax and types, because the preprocessor works on tokens and directives before the compiler checks types, scope, or semantics.

How The Preprocessor Reads Source Text

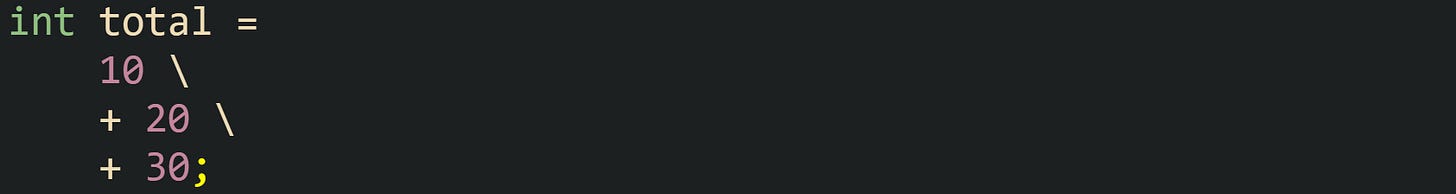

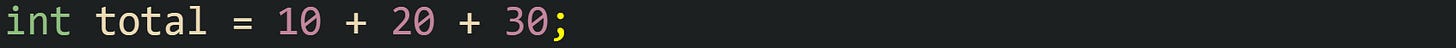

Before real compilation happens, the preprocessor treats the source file as a character stream and then gradually turns that stream into preprocessing tokens and directive actions. Line endings are normalized so that different operating systems and editors do not change how the code is seen. Backslash line continuations are handled at this early point as well. When a backslash sits as the last character on a physical line and a newline follows, those two characters are removed and the next physical line is glued to the end of the current logical line. That lets you split long logical lines in the editor without changing how the compiler eventually reads the expression.

After preprocessing, that sequence is treated as a single logical line:

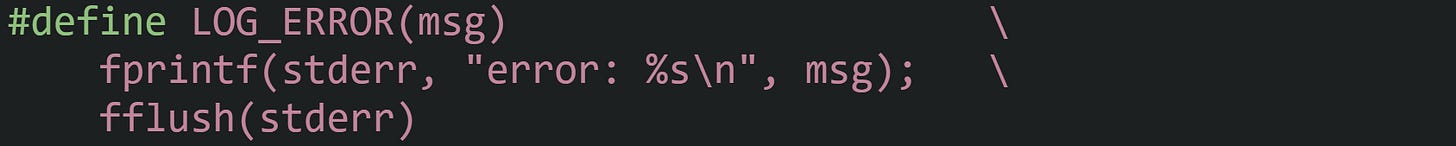

Multiline macros rely on the same rule. A function-like macro that needs more than one physical line uses backslashes at the end of each continued line, and the preprocessor joins those lines before macro parsing.

The macro body above is viewed as one logical sequence of tokens even though it spans several editor lines. That is why a missing backslash can break a macro in confusing ways, because the preprocessor sees a new line where you expected continuation.

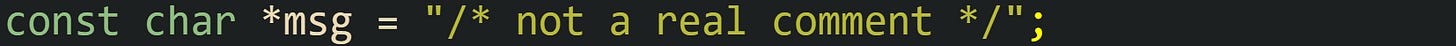

Comments are removed before normal C parsing takes place. Both block comments and line comments disappear, so macros and other directives never see their contents.

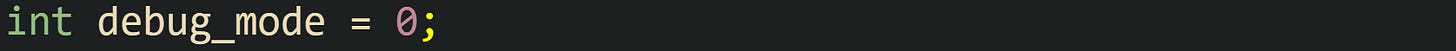

After preprocessing, the text that flows into the compiler looks like:

Comment markers inside string literals are preserved, because those characters belong to the literal and not to the comment system.

That line stays exactly as written through preprocessing, apart from any character set handling that the implementation applies.

After line continuations and comment removal, the preprocessor breaks the text into preprocessing tokens. These tokens include identifiers, numbers, operators, string literals, and also directive lines where # appears as the first non whitespace character of a logical line. Older C standards defined trigraphs and related historical features that were handled during these early phases, but current C standards such as C23 have removed trigraphs, and real projects rarely enable or rely on them, while some compilers still support them as extensions for legacy code. After directives have been processed and macro substitution has finished, the compiler receives a translation unit that no longer contains #include, #define, #if, or comments, only line markers that link positions in the expanded text back to original files and line numbers so diagnostics still point at the right locations.

Include Directives As File Expansion

Source files rarely stand alone. Headers gather declarations, types, and macros into shared files, and include directives tell the preprocessor where to pull those headers into the translation unit. Two common forms appear in code, one with angle brackets and one with double quotes.

Angle brackets guide the implementation to search system include paths such as standard library directories. Double quotes usually mean the directory of the including file and any project specific include paths first, then system directories. Exact search order can differ slightly between compilers and build setups, but that core idea holds across common toolchains.

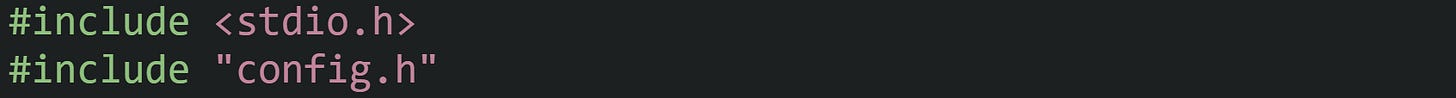

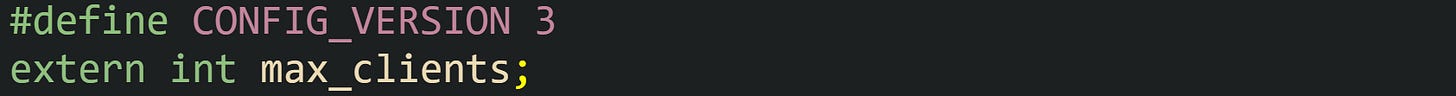

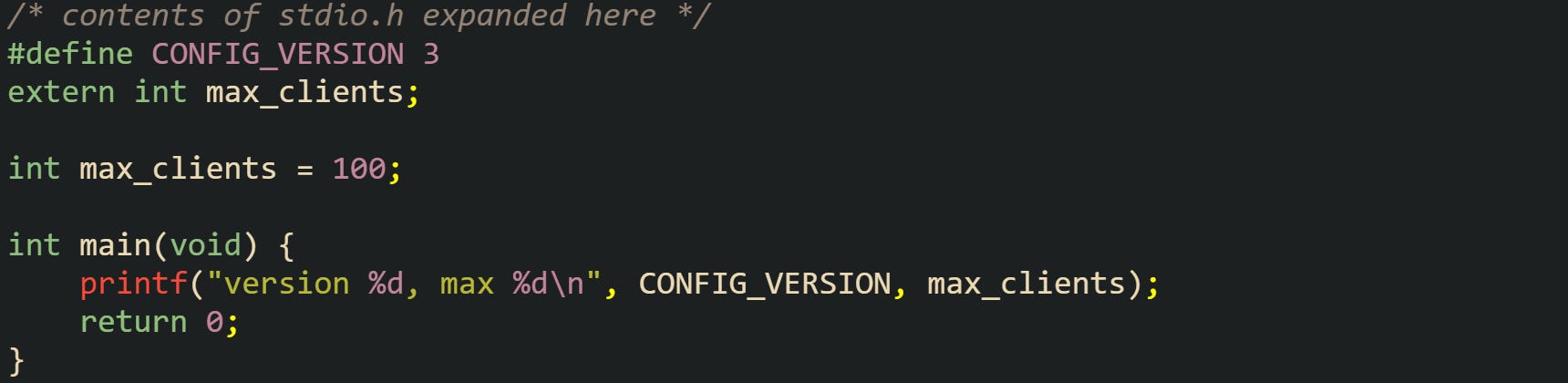

Conceptually, #include works as if the preprocessor copies the contents of the header and drops that text in place of the directive. Take a small example with one header and one source file.

File config.h:

File main.c:

Conceptually, after #include expansion, the compiler behaves as if it sees a combined translation unit like this:

System headers like <stdio.h> are also expanded into their contents before real compilation begins, and those headers often pull in many nested includes. The important idea is that the translation unit is just one big file at this point, built from the original source plus every header brought in by #include.

Include directives do not build a separate namespace for headers. Every declaration and macro that appears in the combined text becomes part of the same translation unit, subject to normal C scoping rules. Declarations from different headers can therefore collide if names match in ways that violate the C rules for multiple declarations and definitions. That is why how headers are written, how #include order is chosen, and how guards are arranged in headers all have a direct effect on compilation.

Nested includes follow the same rule. If config.h itself includes another header, those contents expand into the translation unit at the position of that directive during preprocessing. Complex projects can end up with many levels of includes, which is one reason build systems often provide tools such as precompiled headers, include graphs, and dependency scanners to keep build times reasonable.

Macro Definition Mechanics

Text substitution handled by macros is based on #define directives. Macro introduces a name that the preprocessor recognizes during token scanning and then replaces with its expansion before the compiler sees the code. Macros do not have types, are not functions or variables, and have no presence at link time. They work at this early textual stage only.

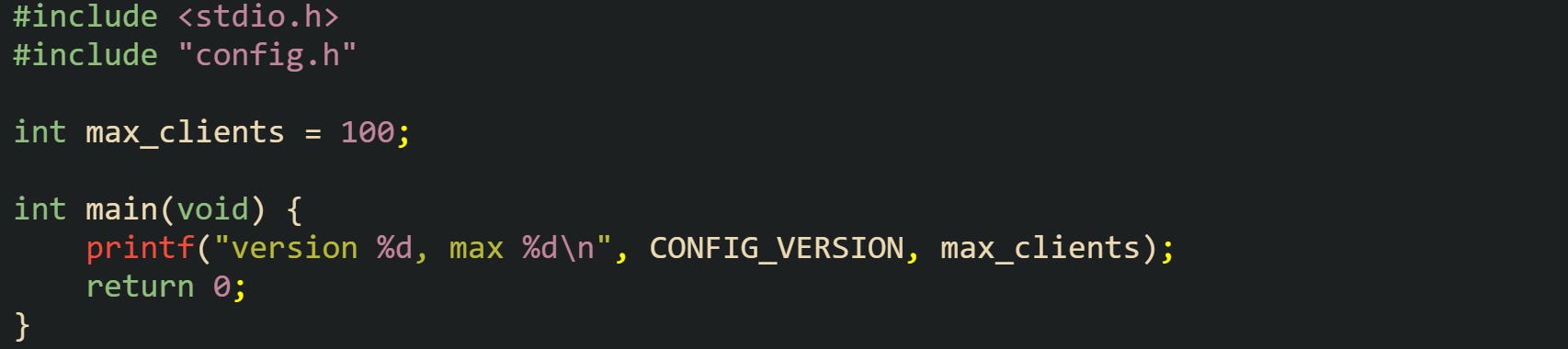

Object style macros act like named values:

After preprocessing, that fragment turns into:

Macro names vanish from the translation unit after expansion. The compiler works only with the replacement tokens, so debuggers normally cannot step through a macro expansion the way they step through a function body.

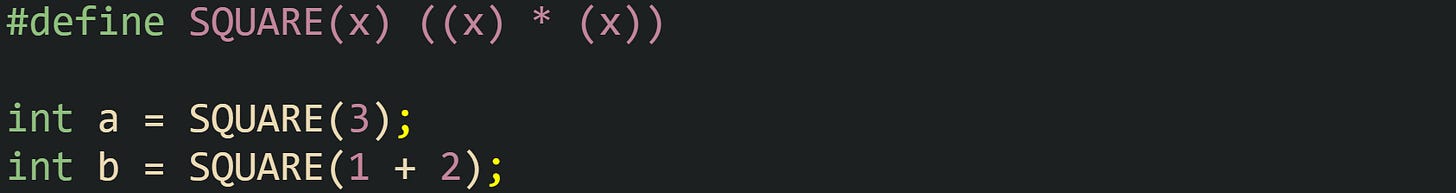

Function style macros accept parameters that are substituted into the replacement list:

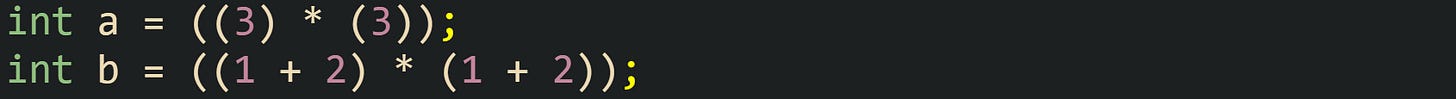

The expanded code seen by the compiler is:

Parentheses wrapped around both the whole expansion and the parameter names in the body keep normal operator precedence rules from changing the meaning of expressions when the macro is used with more complex arguments. Without those parentheses, an expression such as SQUARE(1 + 2) could expand into code that evaluates in a different order.

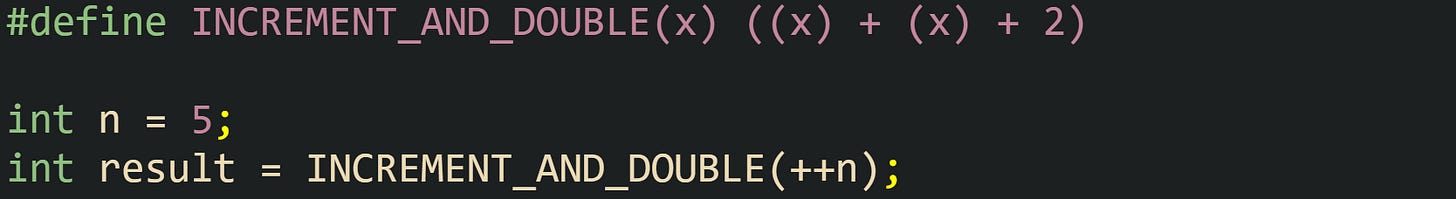

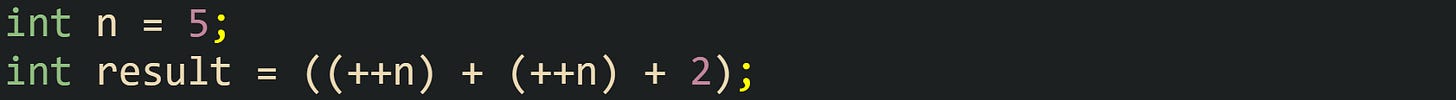

Side effects in arguments can create real correctness bugs with macros, because the expansion can evaluate the same argument multiple times.

After preprocessing, that becomes:

That expression modifies n multiple times without any sequencing rule between those updates, so the behavior is undefined in C. Compilers are free to produce results that do not match the idea of “increment twice in a predictable way.” A normal function with a single parameter would apply the increment a single time before its body runs.

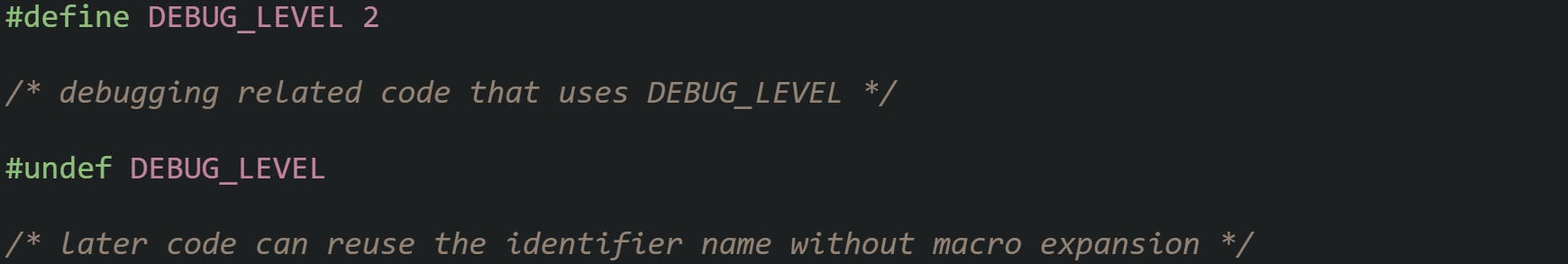

Macros can be removed with #undef so later code no longer sees that substitution:

After #undef, the name DEBUG_LEVEL is no longer treated as a macro name in the remainder of that translation unit. Many headers define a macro, use it to build declarations, then undefine it so application code can reuse that identifier if needed.

C code now tends to use const objects, inline functions, and enumerations when type safety and better debugging are important, and keeps macros for cases where compile time substitution or conditional compilation is necessary. Macros remain central for feature flags, configuration values that affect compilation, and small utility expansions that need to be processed before any type analysis takes place.

Conditional Compilation With Header Guards

Lots of C projects keep multiple build variants in the same source files, such as debug and release builds or different platform targets. Conditional compilation gives the preprocessor a way to choose which parts of that source actually survive into the translation unit that the compiler sees. Header guards use the same mechanism to keep headers safe from repeated inclusion, so a single header can appear in many places without causing clashes in the combined file.

Controlling Code With Conditionals

Preprocessor conditionals such as #if, #ifdef, #ifndef, #elif, #else, and #endif let the source branch before the compiler stage. Only the blocks whose conditions evaluate to a nonzero result are kept, and everything in inactive branches is discarded from the translation unit. That means conditional code does not simply stay disabled at runtime, it disappears during preprocessing.

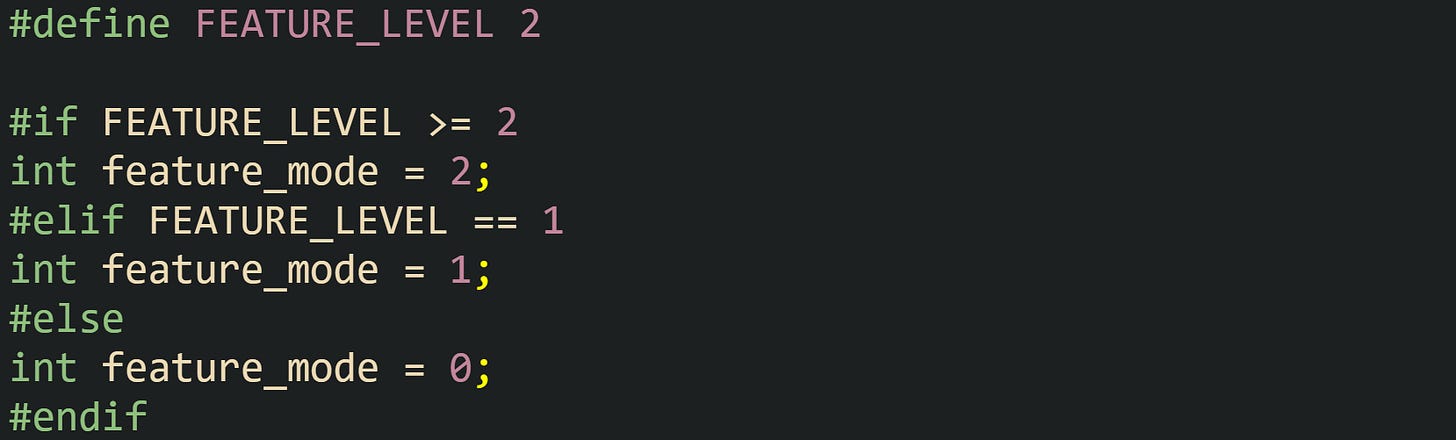

Numeric tests go through #if and #elif. Macro values are treated as integer expressions, and the preprocessor checks those expressions while it scans the file. Common patterns look like:

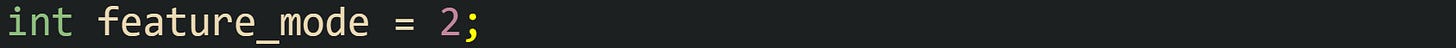

Only one of those three declarations reaches the compiler. If FEATURE_LEVEL is 2 at preprocessing time, the resulting translation unit contains:

And the other branches simply do not exist anymore for the compiler. Changing the macro and recompiling can give a different branch without any runtime checks at all.

Build flags frequently define macros through compiler options. GCC and Clang use -DNAME=value, while MSVC uses /DNAME=value. Compiler command lines can look like this:

That command sets FEATURE_LEVEL inside the preprocessor environment before any source lines are read. It becomes possible to flip features or whole code paths from the build system or from different build configurations in an IDE without editing the C files.

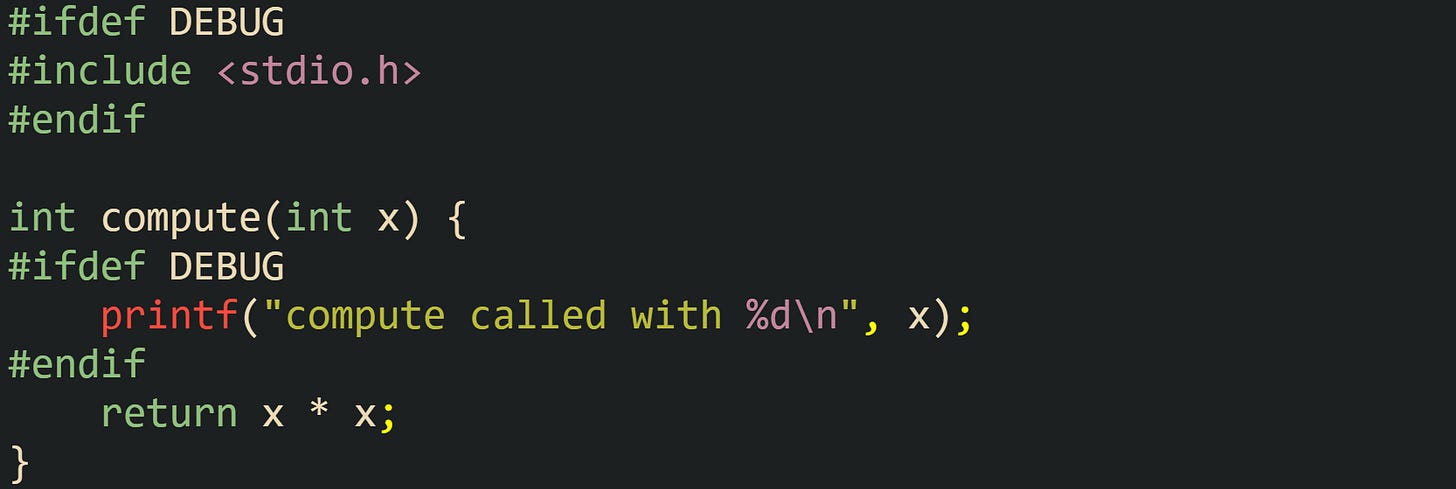

Presence checks use #ifdef and #ifndef, which care only about the existence of a macro name, not its value. Many projects use a debug pattern like this:

When DEBUG is defined, the preprocessor keeps the #include <stdio.h> line and the printf call. When DEBUG is not defined, those lines vanish from the translation unit, leaving a short compute function with a single return statement. There is no runtime branch, only two different versions of the function depending on how the code is compiled.

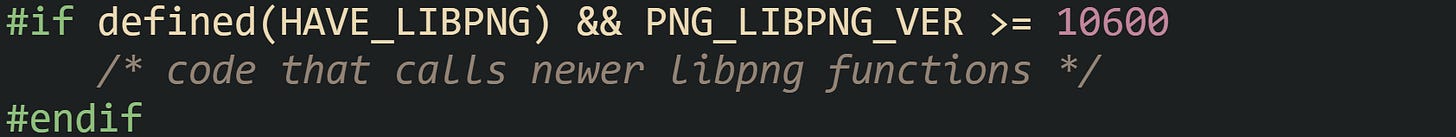

Multiple feature macros can be combined inside a single #if expression with operators such as &&, ||, and !. The preprocessor treats undefined macros as having value zero in #if expressions, which means missing configuration symbols quietly turn a condition to false unless guarded with defined(MACRO_NAME) checks. Library version checks sometimes look like this:

That condition keeps the guarded block restricted to builds that have both HAVE_LIBPNG defined and a PNG_LIBPNG_VER value from a new enough header. Compilers that compile without libpng support or with an older libpng header never see the contents of that block, so they cannot accidentally introduce references to symbols that are missing from the linked libraries.

Header Guard Use In Real Code

Guard macros protect headers from being expanded multiple times into the same translation unit. When many source files include the same header tree, and those headers include one another, it is common for a given header file to be encountered more than one time during preprocessing. Without protection, that can lead to duplicate definitions or redefinitions of the same types and declarations.

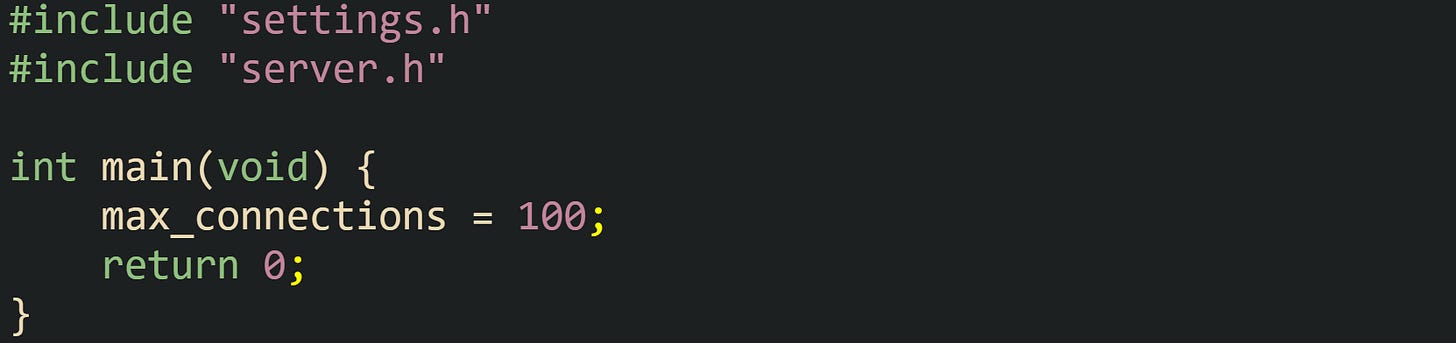

Let’s take a look at a small header and a source file that includes it twice through two different paths. File settings.h:

File server.h:

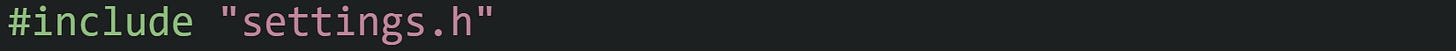

File main.c:

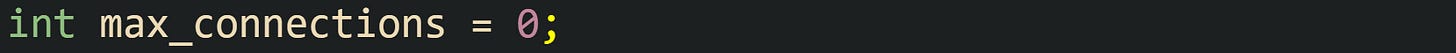

After preprocessing, main.c expands to:

Two definitions of max_connections now appear at file scope in the same translation unit, which violates the C rule that an object definition at that scope must not occur twice in one translation unit. Most compilers report a redefinition error at that point.

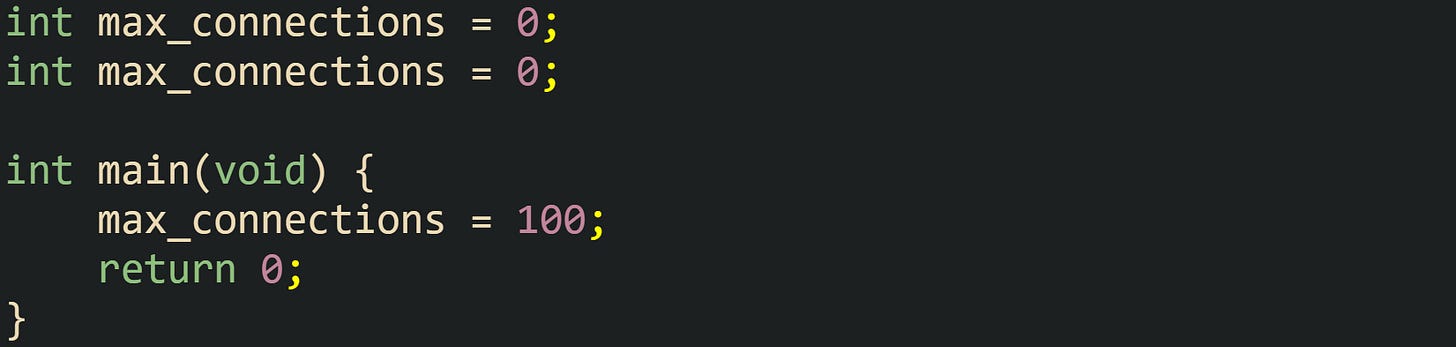

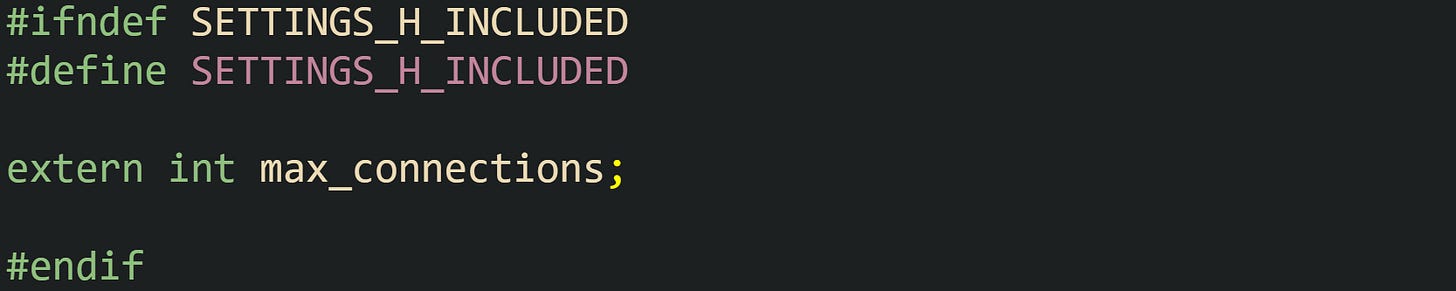

Header guards solve this by wrapping the entire body of the header in a conditional that checks whether a unique macro has already been defined. Only the first inclusion defines the macro and provides the declarations; later inclusions see the macro as already defined and skip the header contents.

The file settings.h with a guard looks like:

Here, main.c stays the same. During preprocessing, the first inclusion of settings.h defines SETTINGS_H_INCLUDED and leaves the declaration of max_connections in the translation unit. When server.h pulls in settings.h again, the #ifndef SETTINGS_H_INCLUDED test fails, so the entire guarded block is skipped. This final translation unit now holds a single declaration of max_connections, and a single definition needs to exist in exactly one .c file to satisfy the linker.

Guard macro names usually reflect the header path and file name in uppercase, with underscores separating components. Names such as PROJECT_SETTINGS_H, MYLIB_SOCKET_API_H, or UTIL_LOGGING_H are common choices. The only strict requirement is that the macro name does not clash with some other macro in the same translation unit, so long, specific names work well.

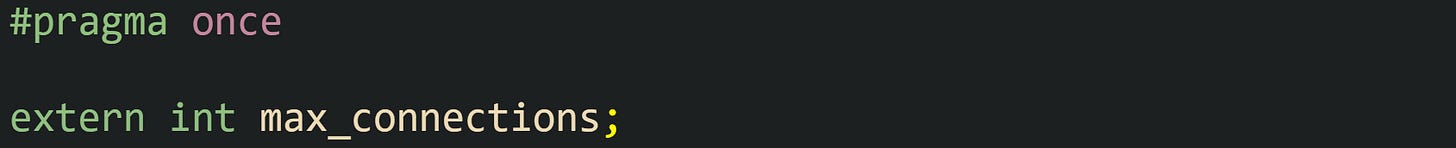

Many compilers also support #pragma once at the top of a header.

This directive tells the compiler to include the contents of the file only one time per translation unit, no matter how many times #include mentions the file. #pragma once reduces the amount of guard boilerplate in headers and gives the compiler a hint that can help it skip redundant work when scanning include graphs. Traditional guards remain important for maximum portability, so real codebases sometimes combine both, with #pragma once near the top and a conventional guard around the entire body for compilers that do not support the pragma.

Conclusion

Preprocessor behavior forms the first active stage in C compilation, turning headers, macros, conditionals, and guards into a single expanded translation unit that the compiler can parse. When you treat #include as text insertion, #define as token replacement, #if and related directives as compile time switches, and header guards as filters that keep headers from repeating, you get a more accurate sense of what actually reaches the compiler for each build. That mental model supports you when you read build errors, write headers for a project, or adjust build flags, because you can trace how the preprocessor rewrites source files before any type checks or code generation begin.

![#define BUFFER_SIZE 2048 #define GREETING_MESSAGE "Hello from C" char buffer[BUFFER_SIZE]; const char *greeting = GREETING_MESSAGE; #define BUFFER_SIZE 2048 #define GREETING_MESSAGE "Hello from C" char buffer[BUFFER_SIZE]; const char *greeting = GREETING_MESSAGE;](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!hYWn!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe1bbb56e-65cd-4b8c-a140-7210eaf95479_1675x282.png)

![char buffer[2048]; const char *greeting = "Hello from C"; char buffer[2048]; const char *greeting = "Hello from C";](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8Yje!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa309b2ab-57ac-4ff4-9caf-622eb7d58fb6_1680x111.png)

Solid deep dive here. The section on header guards makes clear why duplicate inclusion bugs can be so confusing when you don't understand the preprocessor's textual expansion model. I ran into this exact issue last year tracking down redefinition errors, and the guard pattern wasn'tobvious until I understood that the preprocessor literally just copy-pastes file contents in place.