Recursion in the C language rests on the idea that a function can call itself, either directly or through other functions, and each call runs with its own private copy of parameters and local variables. That behavior relies on a call stack, a structured region of memory that keeps track of active function calls. Every time control moves into a function body, the compiled code sets up a new stack frame holding what that call needs, and every time control returns, that frame is removed. Knowing how this process works helps explain why deep recursion can run out of stack space and crash a program, and why stack overflow errors appear the way they do in practice.

How C Executes Recursive Functions

On most systems, recursion in C reuses the same call mechanism that the ABI defines for ordinary function calls on that platform. The call instruction pushes or stores a return address, the stack pointer moves to make room for a new frame, and the function prologue saves any required registers and reserves stack space for local storage before C statements run. Recursive calls follow the same scheme, so one function body can have several frames stacked at distinct depths, all active at the same time. Tooling such as debuggers, stack traces, and profilers reconstruct the call chain from stack frames along with unwind and debug information, which is why they can show the chain of calls that led to the current point in the code.

Function Call Sequence In C

Most C implementations follow a calling convention that articulates how arguments move from caller to callee, where the return value sits, and how the stack pointer changes during the call. Details vary between platforms, but a similar picture tends to appear. The caller places arguments either in registers, in stack memory, or in both, based on rules set by the ABI. The call instruction records a return address, then control jumps to the function entry point. At that entry point, the callee reserves space for its local variables and any saved registers, forming what is called a stack frame.

That frame belongs to one call of that function. It holds everything that call needs to run, including any arguments stored on the stack, local variables, bookkeeping data for stack unwinding, and the address to jump back to after the function returns. When the function reaches a return statement, the compiled code stores the return value in the location required by the ABI, restores saved registers, moves the stack pointer back to release the frame, and then executes a return instruction so control jumps to the recorded return address.

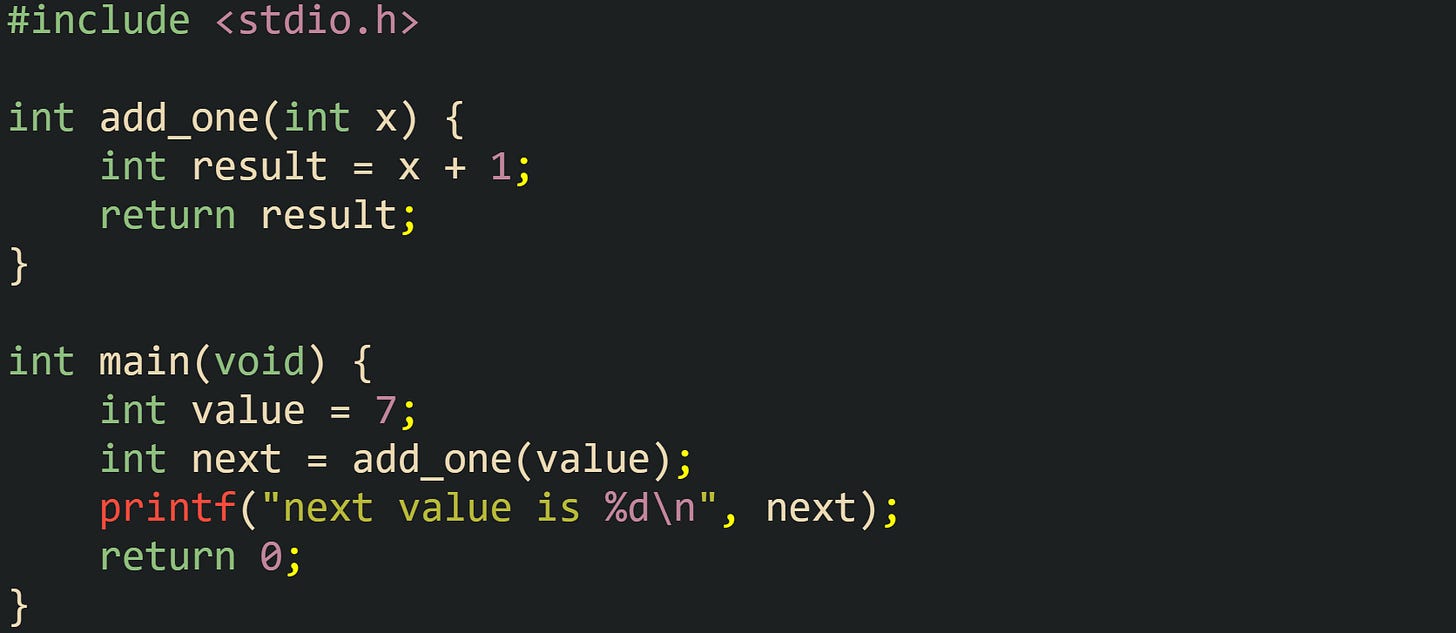

This simple non recursive example helps anchor that idea a bit better in source code form:

The call add_one(value) leads the compiler to generate machine code that prepares value as an argument, runs a call instruction, and sets up a new frame for add_one. Inside that frame, x holds a copy of the argument, result sits in local storage, and the return address for main waits for the function to finish. When add_one returns, its frame is removed and execution in main continues after the call, where next receives the returned number.

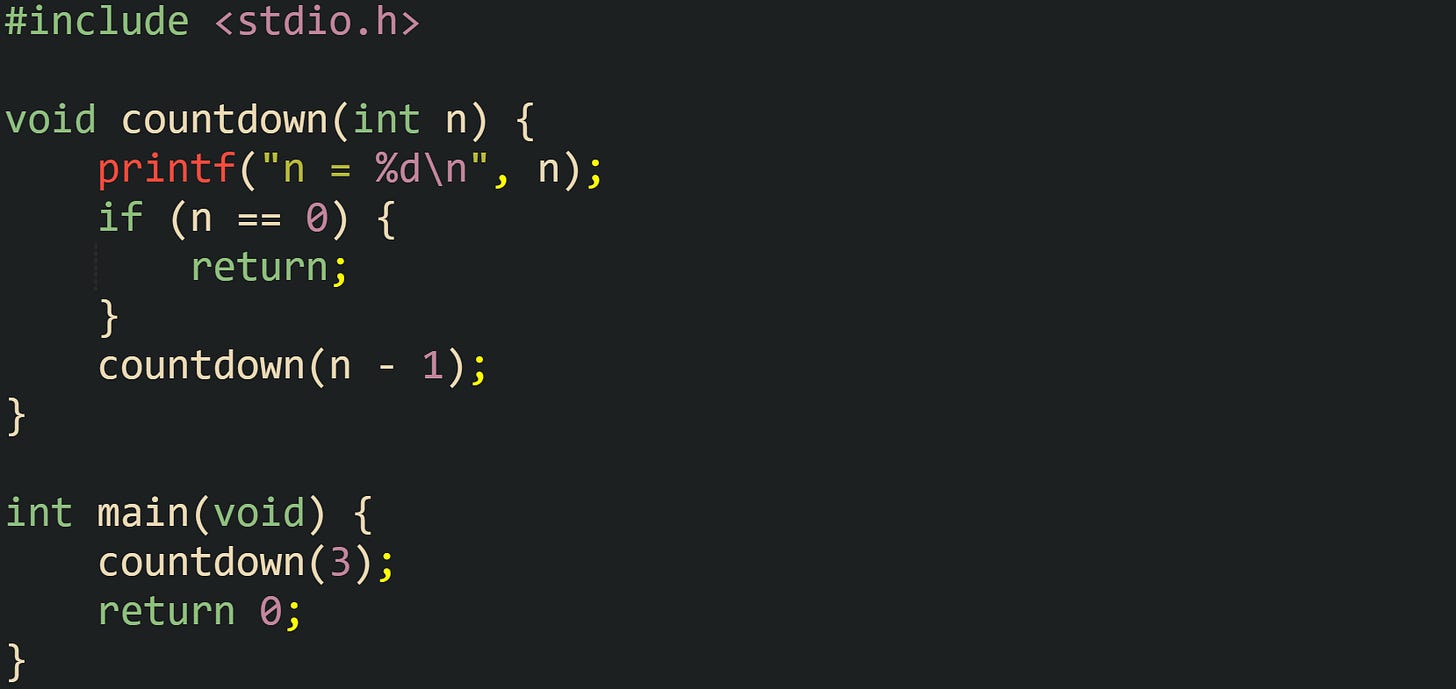

Recursion relies on the same machinery. The only difference is that the callee is the same function that is already active deeper in the call stack. That means the same function body can be running with several different frames at the same time, one per active call. To see that more directly, a recursive function that counts down from a starting value to zero can look like this:

The call countdown(3) creates a frame where n equals 3, prints that value, then calls countdown(2). That second call creates a fresh frame with its own n equal to 2, and the chain continues down to countdown(0). While the deepest call prints and returns, the earlier calls are still suspended with their own frames waiting for those returns. As each return runs, the corresponding frame is removed and control steps back through the earlier calls until main resumes.

Compilers may place arguments in registers for speed when the ABI allows that, or may move some local variables into registers for part of their lifetime, but the logical model stays the same. Every function call has a frame that tracks its state, and recursion means that multiple frames for the same function can be active at the same time.

Stack Frames For Recursive Calls

Each recursive call typically gets its own stack frame, even though all those frames come from the same source code. Parameters and local variables stay tied to that call while it is active, and the frames are released one by one as control returns. Compilers can sometimes apply tail call optimization and reuse a frame for certain tail recursive calls, so the one frame per call picture is the usual model, not a rule.

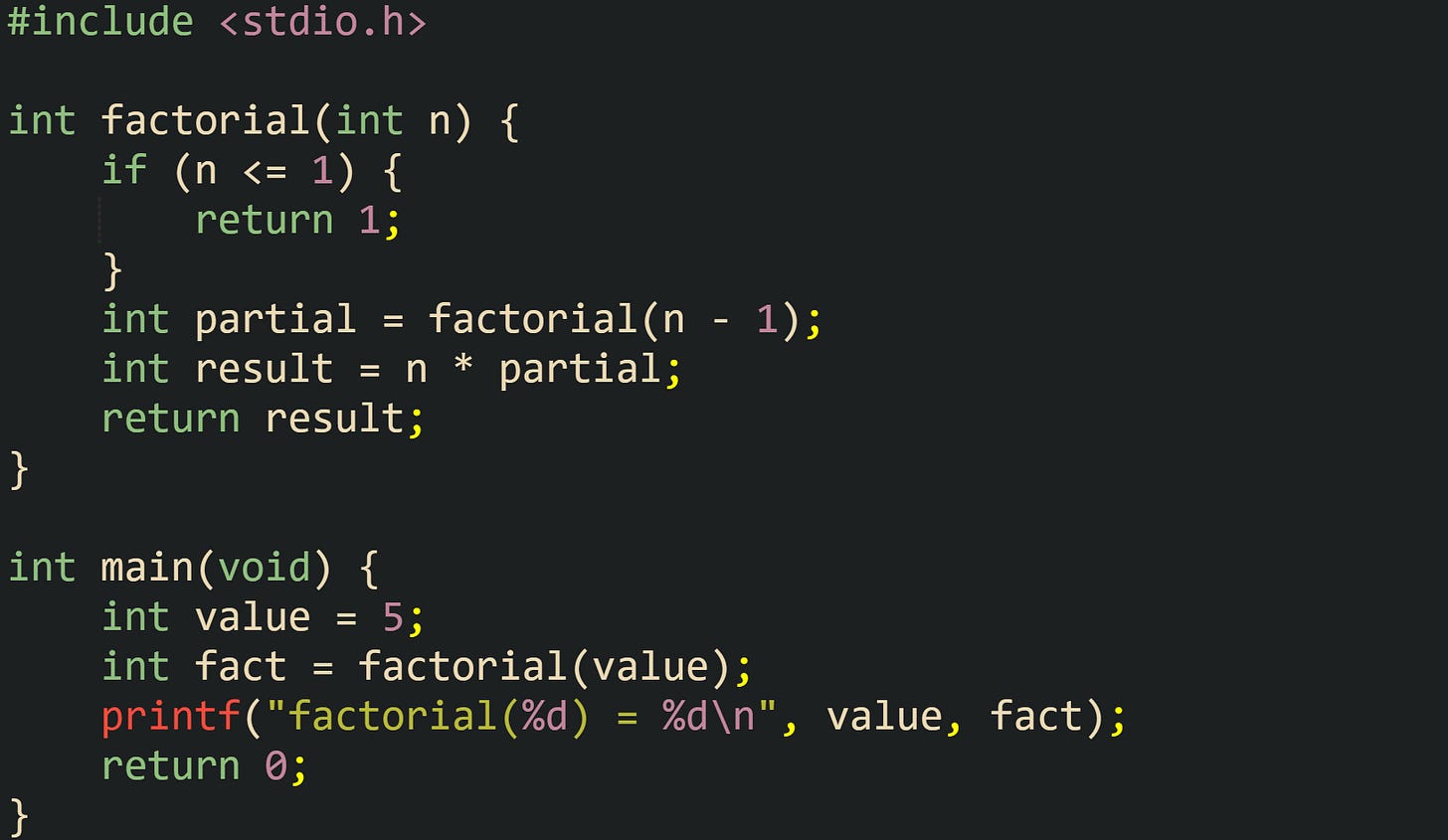

The classic factorial function helps make this separation easier to understand visually:

During the call factorial(5), the first frame holds n equal to 5, plus the local variables for that call. The condition n <= 1 is false, so the function calls factorial(4). That call creates another frame with its own n equal to 4 and its own partial and result variables. The call chain continues until factorial(1) runs with n equal to 1 and returns 1. At that deepest point, the stack holds a sequence of frames, one for each call with n set to 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1. When factorial(1) returns, its frame is removed. The caller factorial(2) retrieves that return value into partial, computes result, returns, and so on, until the original call returns to main.

Local variables in one frame never share storage with local variables in another frame from the same function while both calls are active. They may share names in the source code, but the compiler maps those names to different stack locations or registers in each frame. Global variables and static variables are different, because they live in separate storage regions that do not depend on the call stack. A recursive function that updates a global counter, for instance, has every frame reading and writing the same memory location, while its parameters and ordinary locals stay private to each call.

To see per call data a bit more directly, a recursion that sums a small prefix of an array is helpful:

During a call such as sum_prefix(data, 4), the frame holds values, count, last_index, and partial for that level. The recursive call sum_prefix(values, 3) creates a new frame with its own count, last_index, and partial. While the deeper call runs, the outer frame is suspended. When the deeper call returns, execution continues in the outer frame, which still has its local variables untouched by what happened in the inner call.

This separation of frames is the reason recursion can treat each step as if it lives in its own small world, with parameters and locals that match that step only. At the same time, the call stack gives a strict order for entering and leaving those worlds, so every return goes back to the correct caller with the expected state waiting to resume.

Stack Behavior in Deep Recursion

Deep recursion places one frame after another on the call stack, all belonging to calls that have not yet returned. Every new call reserves a fresh frame with its own bookkeeping and local data, while older frames stay parked underneath waiting for control to come back. That stack of frames limits how far recursion can go, because the stack region for a thread has a fixed size and every frame consumes part of it.

Before stack overflow makes sense, it helps to look at two separate pieces. First comes the layout of parameters and local data inside a single frame. Then comes the relationship between frame size, total stack size, and the depth that recursion can reach before memory for frames runs out. With that base in place, stack overflow turns into a predictable consequence of running past the available stack region.

Layout Of Parameters And Local Data

On typical C targets, the call stack is a contiguous region of memory reserved for frames. Each frame usually holds a saved frame pointer or base pointer, the return address, arguments that live on the stack, local variables, and sometimes padding bytes so that data lines up with alignment rules from the hardware. Exact order and spacing come from the ABI and compiler options, but those same pieces show up repeatedly in frame after frame.

Recursion does not change what goes into a frame. The compiler still emits a prologue that adjusts the stack pointer and reserves room for locals, and an epilogue that restores the previous state on return. Deeper calls just repeat that sequence, so two frames from the same function can sit next to each other in memory while holding different parameter values and distinct local data. Debugger stack views that list several entries for one function are simply walking these frames in order, with the most recent call at the top.

Code like this string length function gives a nice view of how parameter values move with depth:

During a call such as str_length(name), the frame holds the pointer s and the local variable rest for that call. When str_length calls itself with s + 1, a fresh frame appears with a new copy of s pointing one byte later in the string and its own rest slot. Earlier frames remain on the stack with their original pointer values, waiting for deeper calls to return so they can finish their own additions.

Local arrays and large structs in a recursive function can increase the size of every frame. When a function places a sizable buffer on the stack, each recursive call allocates another copy of that buffer, so the stack usage grows in proportion to depth. Global and static objects behave differently, because they live in separate storage regions that do not expand when recursion goes deeper.

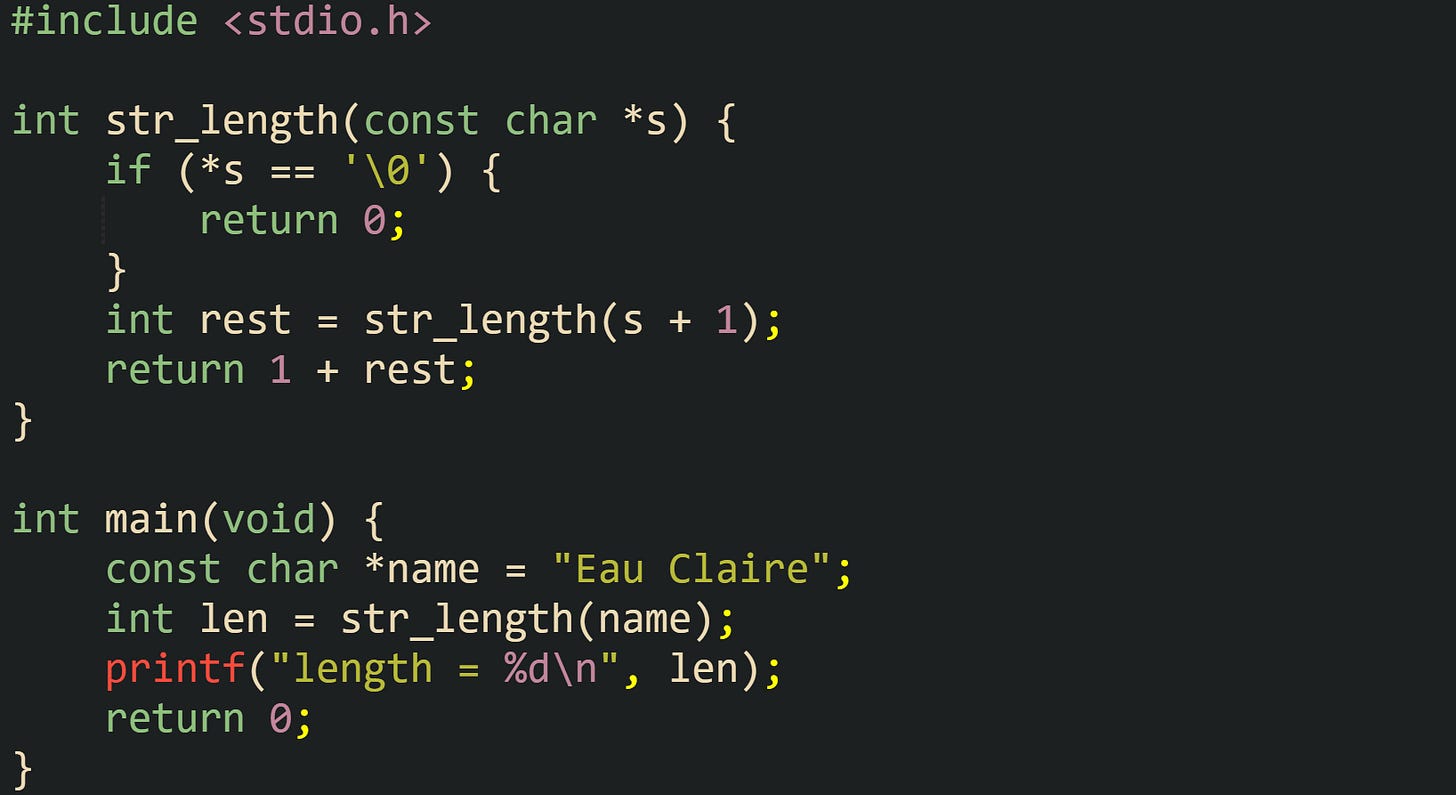

When a buffer is allocated as a local array inside a recursive visitor, stack usage becomes very easy to see:

Every call to visit_level allocates one buffer on its frame, so at depth 100 there are 101 separate arrays in stack memory, one per active call. The total stack space used by these arrays grows linearly with call depth, on top of the fixed overhead for return addresses and saved registers that appears in every frame.

Call Depth Versus Stack Size

Every thread in a C application runs with a stack that has a finite size, configured by tools such as the linker, environment limits, or thread creation options. That size sets an upper bound on how many frames can fit at once, given the average frame size for the calls on that stack. Deep recursion pushes a fresh frame for each call, so the maximum safe depth depends on how much space each frame takes and how much stack remains at the moment recursion starts. Frame size comes from several pieces. Saved registers, the return address, arguments stored on the stack, local variables, alignment padding, and any hidden data the compiler needs for features such as variable length arrays all contribute. When a recursive function declares a small number of scalar locals, its frame tends to stay modest, while a function with large arrays or complex structs as locals can consume far more stack per call.

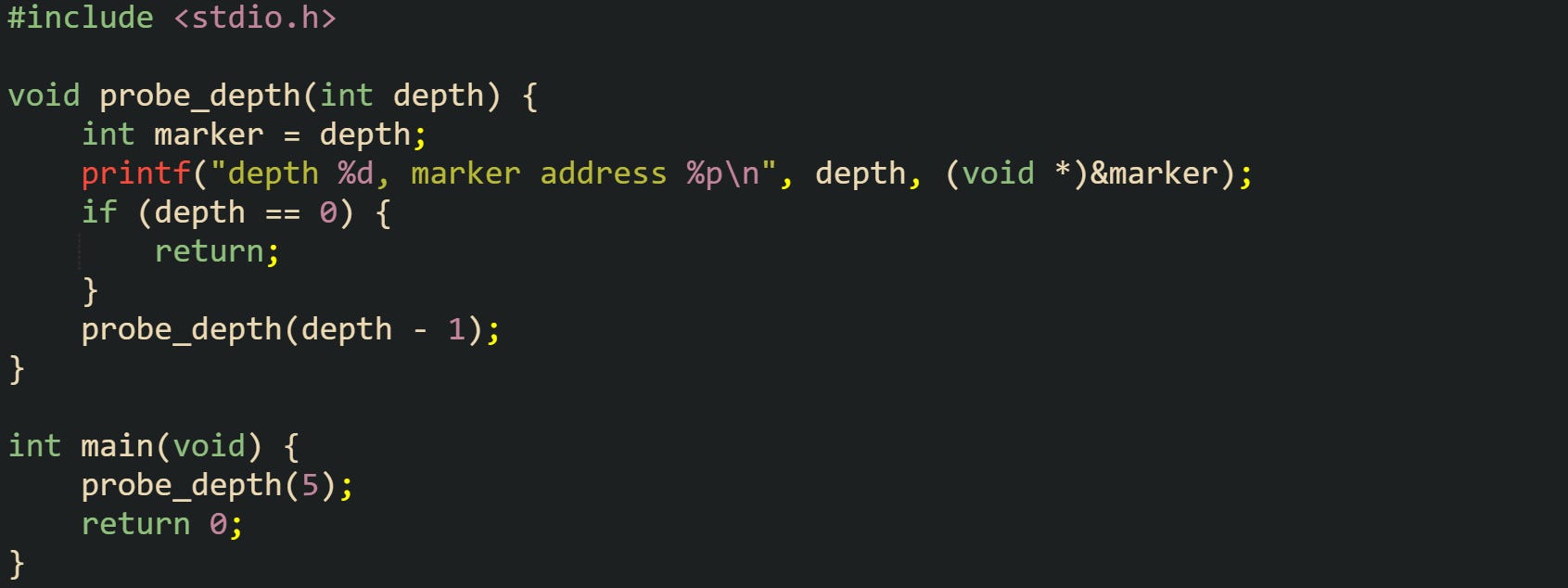

A debugging helper that prints the address of a local variable at each depth can make stack growth visible:

Output from this run shows marker addresses changing in one direction as depth increases, reflecting frames that move through the reserved stack region for that thread. In many builds, a small function like probe_depth ends up with a consistent frame size, so each deeper call adjusts the stack pointer by the same amount and the printed addresses look evenly spaced. Compiler settings and the target ABI can change that, so the spacing is a clue, not a guarantee.

Stack size defaults differ across platforms. Desktop operating systems usually grant several megabytes per thread, while embedded systems may offer far less. Toolchains for some targets provide flags or configuration files that adjust stack size, and thread libraries allow custom stack reservations when starting a new thread. Those settings interact with recursion depth, because a larger stack headroom allows more frames before overflow occurs.

The C standard does not promise any particular stack size and does not define precise behavior at the point where stack space runs out. That lack of a guarantee means developers need to treat maximum recursion depth as a property of the platform and build process, not as a fixed number from the language alone.

What Stack Overflow Looks Like

Stack overflow appears when recursion keeps adding frames until the stack region for that thread has no room left for another frame. At that point, the next write can cross a memory protection boundary and trigger a segmentation fault or access violation, or the operating system can trip a guard page around the stack and raise a stack overflow style exception. From the C language point of view, this situation falls under undefined behavior, so the standard leaves details to the platform.

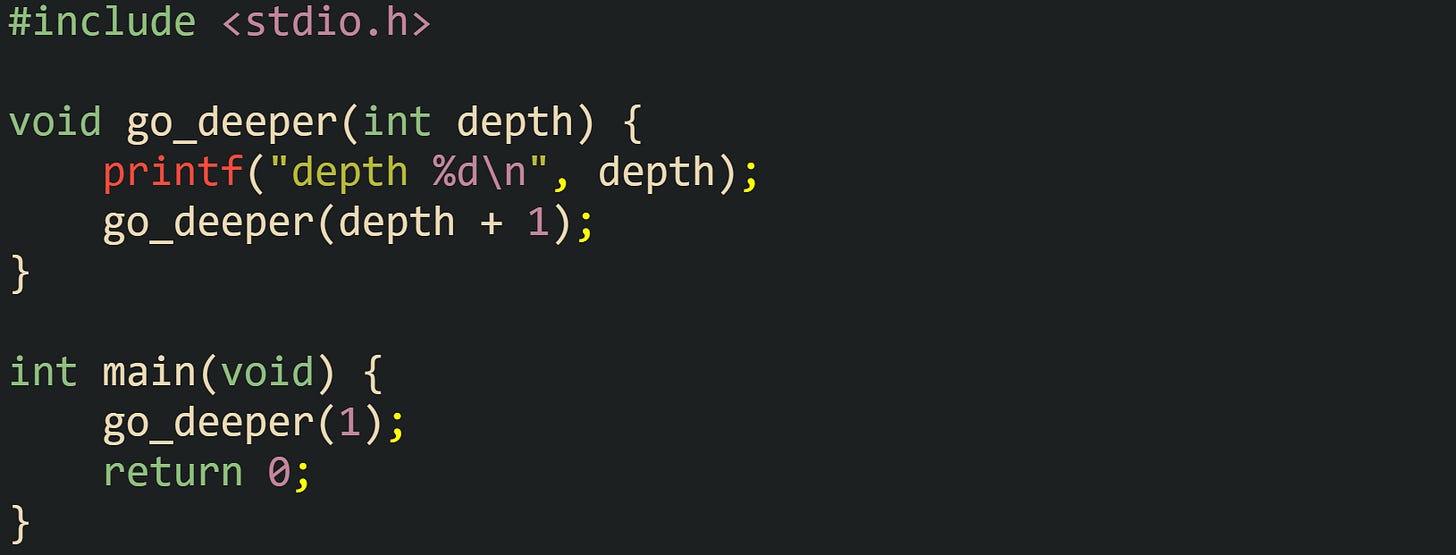

Runaway recursion that never hits a base case gives a textbook stack overflow example:

This function keeps calling itself with larger depth values, never returning to the caller, so frames accumulate until the stack limit is reached and the process fails with an error such as a segmentation fault or stack overflow exception, depending on the operating system. The exact depth that triggers failure depends on default stack size and frame size for this function, and those in turn come from build settings and the target environment.

Bugs that cause stack overflow are not always as obvious as a missing base case. Some functions have a base condition that works for certain inputs but not for others, so a rare data layout triggers recursion that never terminates. Recursive parsers, tree visitors, and search functions can all run into this situation when they do not handle a particular branch or cycle in the data structure. The result looks the same, frames continue to accumulate until stack space is exhausted, and the process stops with a low level memory error.

Debugger backtraces for stack overflow usually contain a long sequence of repeated function names with changing argument values. Tooling may even truncate the list or summarize repeated frames because the chain grows so long. That visual cue points directly at runaway recursion in one function or in a small group of functions that call one another in a cycle, and it guides debugging work toward base cases and state changes that control recursion depth.

Conclusion

Recursion in C rests on how the call stack holds one frame for each active call and how those frames are created on entry and removed on return. When someone traces how parameters, local variables, and return addresses move through that stack, it becomes possible to judge how a recursive function behaves, how deep it can safely go, and what happens when that depth is pushed too far. Thinking in terms of frames and stack space ties the source directly to what the processor and runtime do during execution, which makes stack overflows and call traces easier to read and reason about.

![#include <stdio.h> int sum_prefix(const int *values, int count) { if (count == 0) { return 0; } int last_index = count - 1; int partial = sum_prefix(values, last_index); return partial + values[last_index]; } int main(void) { int data[] = {3, 5, 8, 10}; int total = sum_prefix(data, 4); printf("sum = %d\n", total); return 0; } #include <stdio.h> int sum_prefix(const int *values, int count) { if (count == 0) { return 0; } int last_index = count - 1; int partial = sum_prefix(values, last_index); return partial + values[last_index]; } int main(void) { int data[] = {3, 5, 8, 10}; int total = sum_prefix(data, 4); printf("sum = %d\n", total); return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!q0YA!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F22fb527f-2a78-4535-af4b-7ddc844572f4_1639x951.png)

![#include <stdio.h> void visit_level(int depth) { char buffer[1024]; buffer[0] = (char)('0' + (depth % 10)); if (depth == 0) { printf("bottom depth\n"); return; } visit_level(depth - 1); } int main(void) { visit_level(100); return 0; } #include <stdio.h> void visit_level(int depth) { char buffer[1024]; buffer[0] = (char)('0' + (depth % 10)); if (depth == 0) { printf("bottom depth\n"); return; } visit_level(depth - 1); } int main(void) { visit_level(100); return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4FW9!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe9699d4b-d43b-41f7-aa2b-8decf5dff60c_1638x896.png)