C code that works with structured data usually relies on structs stored as contiguous blocks of bytes in memory. The layout of those bytes doesn’t come from random choices, because compilers follow rules about alignment and padding so each field in a struct sits at an address that suits the target architecture. These rules affect sizeof, performance, and how well a struct layout matches data stored in files or sent over a network. Recent C standards also provide alignment features that work with platform ABIs to produce the layouts that real binaries use.

Struct Layout In Memory

Structs in C tie directly to the target architecture and the C implementation. Each object of struct type has a size reported by sizeof, an alignment requirement, and a fixed sequence of fields that matches the order written in the source. Compilers are free to insert padding bytes between fields and at the end of the struct, but they keep the relative order of fields intact and respect the alignment rules for each field type.

Every struct object also has a single address that corresponds to its first byte in memory. The standard treats the struct as one object, while at the same time treating each field as its own object that lives inside that memory range. Reading or writing through a field expression such as p->count accesses bytes at an offset from the base address, and that offset stays stable for a given implementation and target ABI. Layout details fall under implementation defined rules, yet the standard still guarantees that field order matches the declaration and that no field overlaps a different one in storage.

The C11 standard introduced the _Alignof and _Alignas keywords and the <stdalign.h> header, which defined alignof and alignas macros that map to those operators. C23 adds alignof and alignas as keywords, deprecates _Alignof and _Alignas, and defines <stdalign.h> as an empty header with no macros. Older compilers also provide extensions such as __alignof__. With these features, code can query alignment for a type or request stricter alignment for particular struct types or variables, and then relate sizeof and field offsets to alignment rules that come from the platform ABI.

How C Defines Struct Objects

In C, a struct definition introduces a type that groups named fields, each with its own type, in a fixed order. Each object of that type occupies a contiguous region of memory large enough to hold all fields plus any padding bytes the implementation adds. The address of a struct expression points at its first byte, and field access expressions work as offsets inside that region. The C standard requires that fields appear in memory in the same order as in the definition, with each field located at a higher or equal address than the previous one.

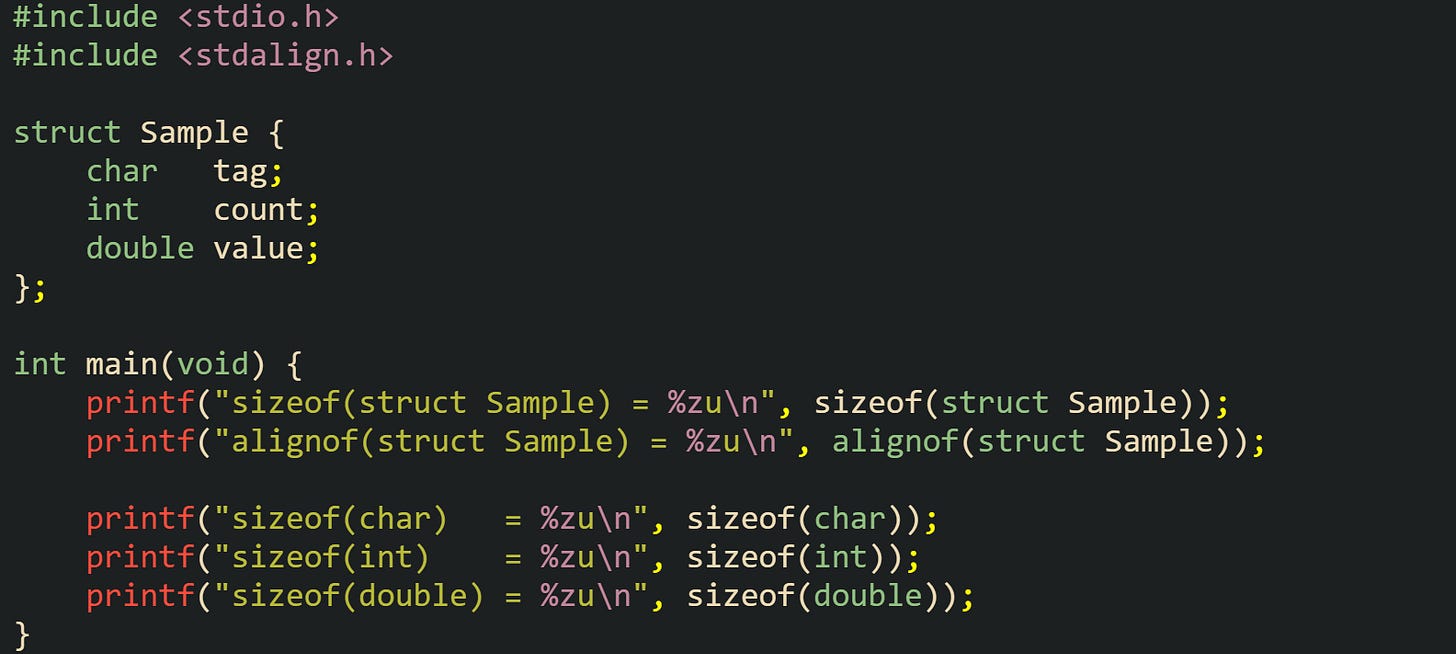

Take this example that helps map these rules to output from a compiled binary:

Output from a compiler shows that sizeof(struct Sample) is at least the sum of the field sizes, and frequently larger because the compiler adds padding so that count and value sit at aligned addresses. The value printed for alignof(struct Sample) is at least the strictest alignment requirement among its fields. On many common 64 bit targets it ends up equal to the alignment of double, but the implementation may choose a stricter alignment for the struct type.

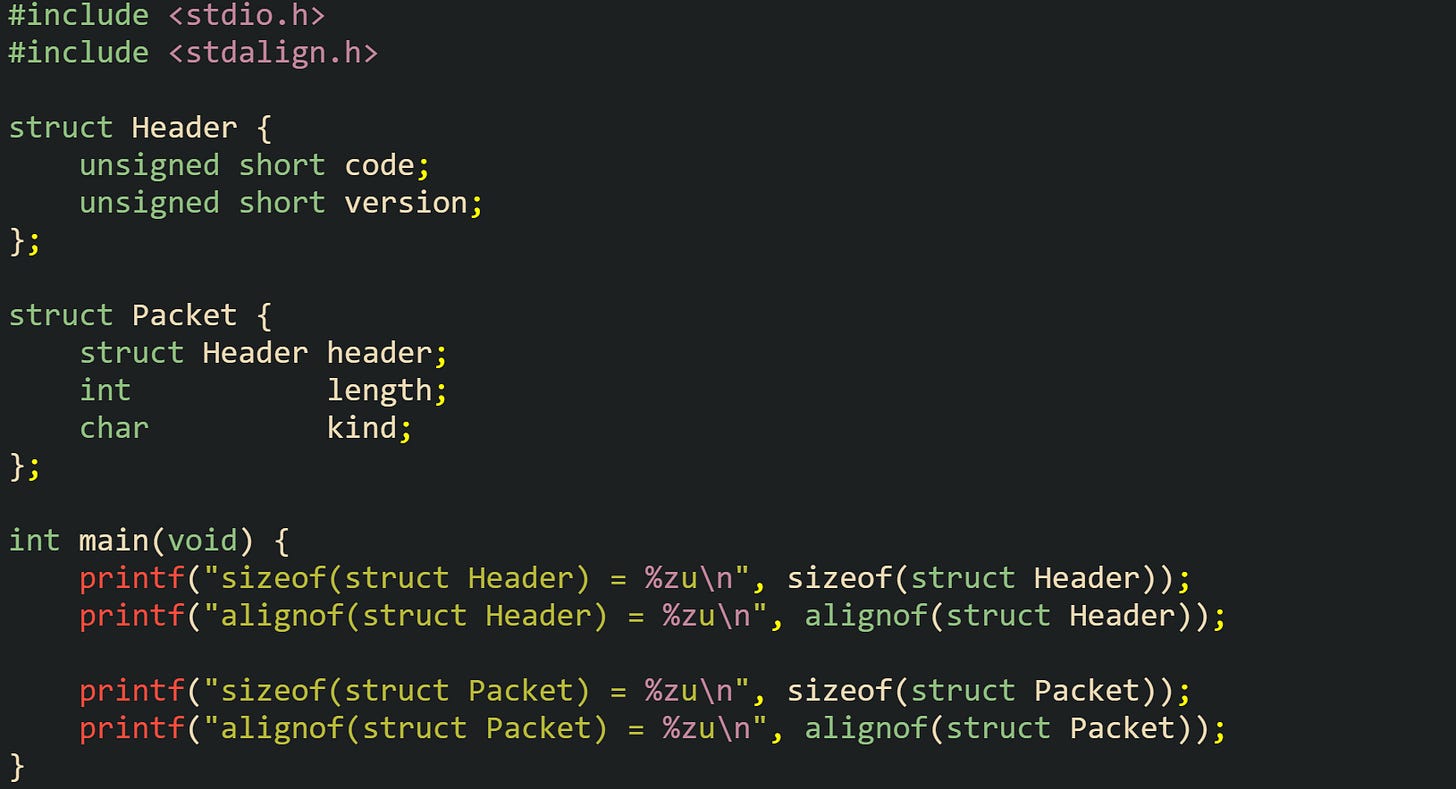

Nested structs follow the same basic rules. An inner struct is treated as a single field inside an outer struct, with its own alignment and size, and the compiler chooses an offset for the inner struct that respects that alignment.

Here, the Packet object begins with the Header bytes in the same layout that Header would have on its own, followed by any padding the compiler decides to insert, followed by length and then kind. The standard does not permit the compiler to move length ahead of header, or to interleave bytes from different fields.

The standard defines how copying behaves for structs rather than giving a built in equality operator. An assignment such as dst = src for two struct objects of the same type copies the value of src into dst. When a value is stored in a structure object, any padding bytes in the object representation take unspecified values, so structure assignment may copy padding bytes or may not. Two struct objects of the same type and same field values therefore need to be compared field by field in portable C, because padding bytes can differ even when all fields match. Interfaces such as memcpy work on the object representation of a struct and copy every byte in that representation, including padding, so byte wise comparison with memcmp is not a safe stand in for field wise comparison when padding is present.

Field Order With Padding Rules

Alignment rules for each field type drive the padding that appears inside a struct. Each type has an alignment, which is a positive integer in bytes. The implementation guarantees that any object of that type has an address that is a multiple of its alignment, and that guarantee extends to fields inside a struct. For C11 and later, _Alignof(T) and alignof(T) report that alignment value for a type T.

For a given struct definition, the compiler walks the fields in order, places the first field at offset zero, then for each later field chooses the smallest offset that is greater than or equal to the previous field end and that also satisfies the alignment for the new field. Padding bytes fill any gap that appears between fields. At the end, the compiler may add trailing padding so that the overall struct size is a multiple of its alignment. Trailing padding matters for arrays of structs, because it keeps every element aligned the same way as the first one.

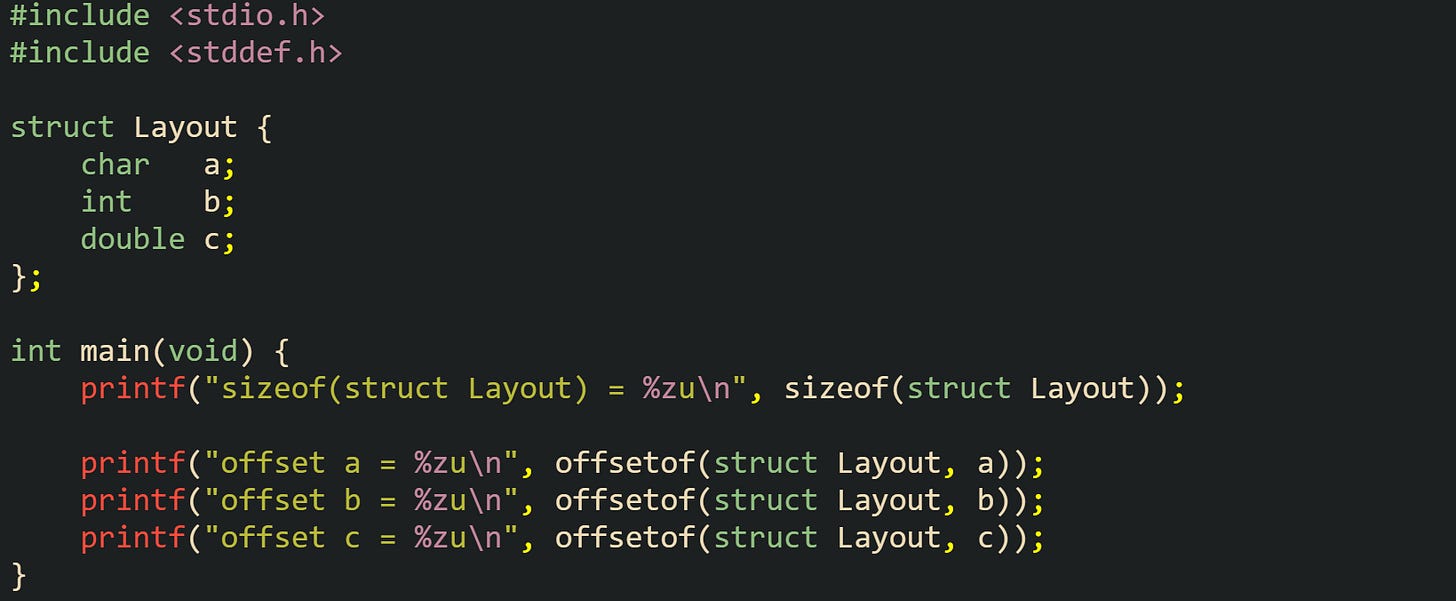

Field offsets become visible with the offsetof macro from <stddef.h>:

On many 64 bit builds, a appears at offset zero, b at offset four, and c at an offset that is a multiple of eight, with trailing padding bringing the total size to a multiple of eight as well. Exact numbers depend on the ABI and compiler options, yet within one build those offsets stay consistent and support code that relies on them, such as low level serialization.

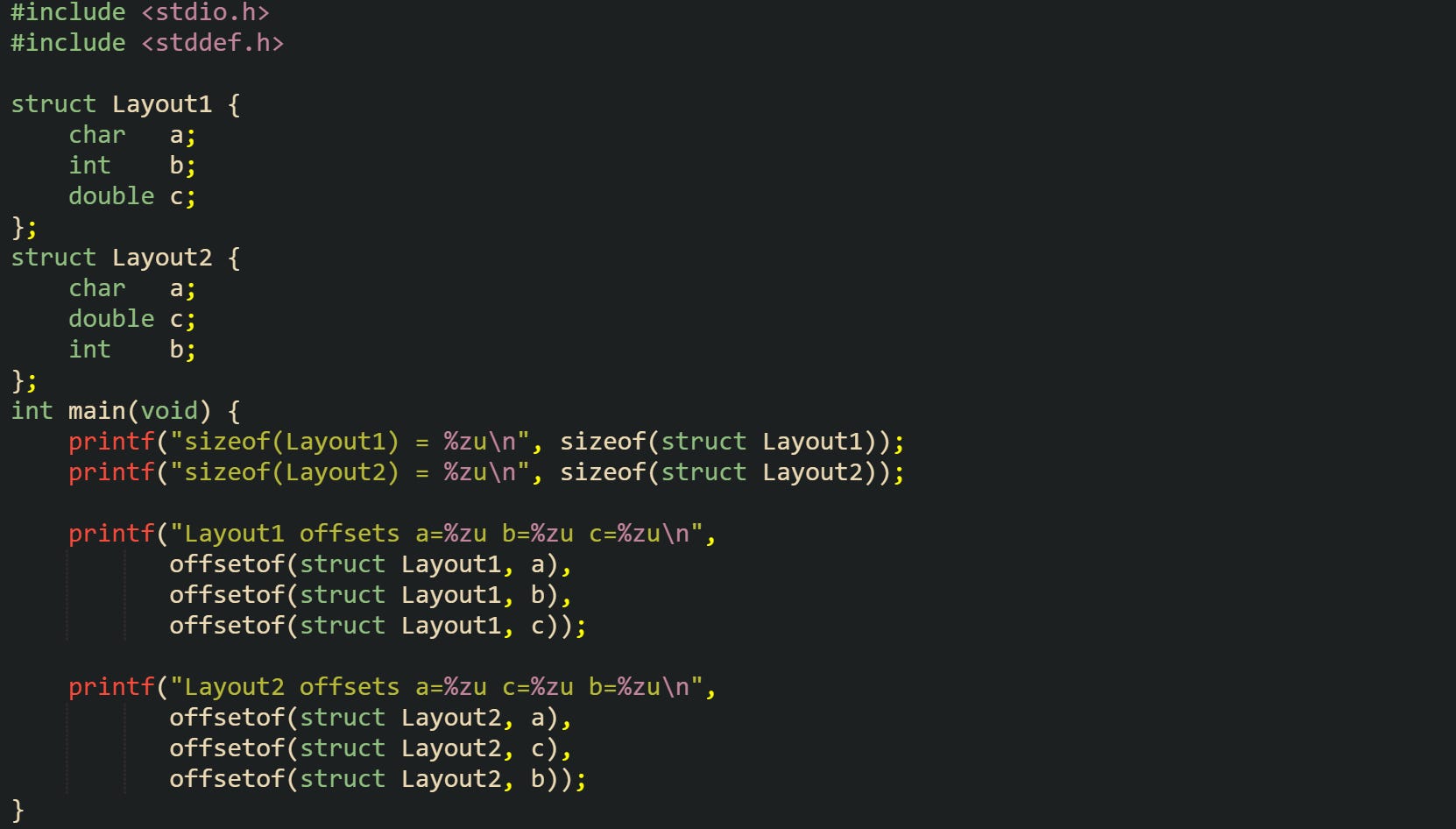

If field order changes, padding changes too, even though the field types stay the same. That effect can help when work needs a smaller struct, or when memory layout must match a specific external format.

By swapping the order of b and c, the compiler can place c at offset eight directly after the first byte, while b follows c. Padding bytes in the middle or at the end change accordingly. Both structs still obey alignment for int and double, but one layout can waste more padding than the other, which affects sizeof and cache footprint for arrays of those structs.

Alignment control can also be pushed in the other direction, with stricter alignment requested for stored objects than the default rules would give.

Here the alignas(16) specifier on arr asks the compiler to place that array at an address that is a multiple of sixteen bytes. arr[0] starts on a 16 byte boundary. Later elements start sizeof(struct Block) bytes apart, so they land on 16 byte boundaries when sizeof(struct Block) is a multiple of 16, which is common for two double fields on typical 64 bit targets. The usual alignment and padding rules inside struct Block still apply, so field offsets respect both their own alignment and the stricter alignment chosen for the array.

Alignment impact on sizeof plus performance

Rules for alignment affect more than where fields sit in a struct, because they also change what sizeof reports and how quickly loads and stores run. On hardware with strict alignment rules, access to misaligned addresses can trap or require extra microcode work, while x86 families usually allow misaligned access at a cost in cycles and cache behavior. Compilers place fields so that loads and stores for each type meet alignment requirements by default, and packed layouts or manual byte control move away from that default in exchange for predictability of offsets. The details look different on 32 bit and 64 bit platforms, and those layouts interact with file formats and network protocols that already define their own byte order and alignment rules.

Alignment on 32 bit platforms

On many 32 bit platforms the C implementation follows an ILP32 model, where int, long, and pointer types use 32 bit storage, while types such as long long and double extend beyond that size. For a common 32 bit x86 target with GCC or Clang, char normally has size 1 with alignment 1, short has size 2 with alignment 2, int, long, and pointer types have size 4 with alignment 4, float has size 4 with alignment 4, and double has size 8 with alignment 4 or 8 depending on the ABI rules. Those numbers give the background for how compilers choose struct layouts, because each field inside a struct still has to sit at an address that honors its own alignment.

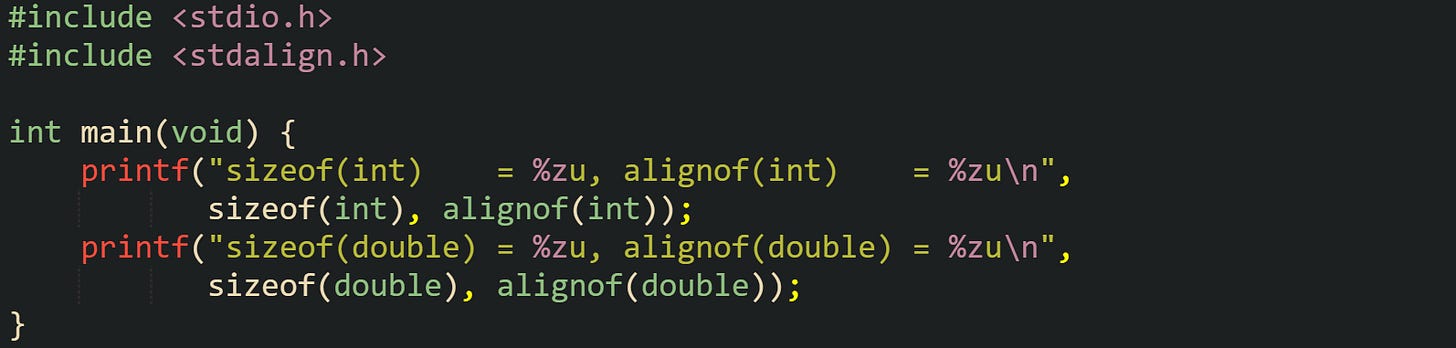

Take this code that prints sizes and alignments for two fundamental types:

Output from a real build lets a developer confirm the size and alignment for core types on the 32 bit configuration in front of them, so later reasoning about struct layout starts from values reported by the compiler instead of guesses.

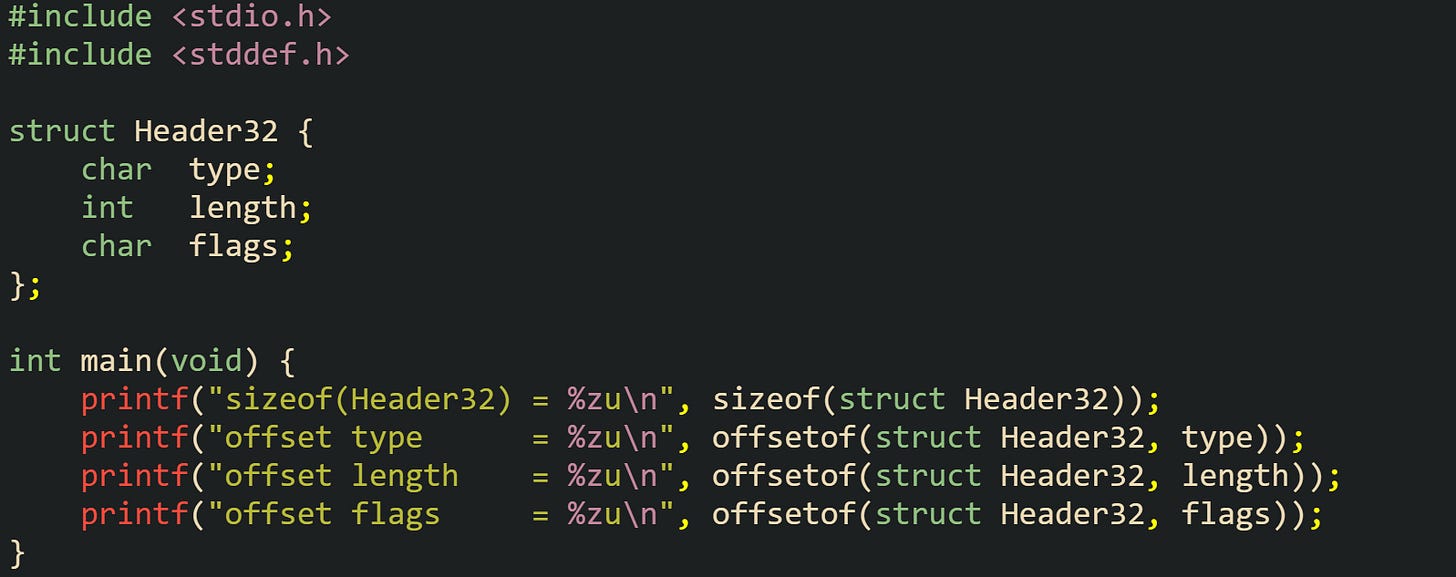

Structs on 32 bit platforms follow the same placement rules as on 64 bit builds, yet alignment values lead to different padding arrangements. One small header struct with different types makes that behavior easy to see:

For a typical ILP32 ABI, type occupies offset 0, then three bytes of padding appear so that length starts at offset 4, and flags follows length at the next byte. Trailing padding brings the total size to a multiple of the strictest alignment among the fields, which is usually 4 bytes in this configuration. Arrays of Header32 then have each element separated by sizeof(struct Header32) bytes, with every length field naturally aligned inside the array.

Hardware effects show up when code accesses misaligned words. On older ARM or MIPS cores, a misaligned 32 bit or 64 bit load can raise a trap if the address does not meet the required alignment, so either the compiler has to split such accesses into multiple aligned pieces or the operating system has to emulate the operation after the trap. On 32 bit x86, misaligned access tends to work at the instruction level but leads to extra cycles or multiple micro-operations inside the processor. Packed structs that remove padding bytes on 32 bit targets therefore trade some speed and complexity for exact byte-level layouts.

Alignment On 64 Bit Platforms

On 64 bit platforms an LP64 model is common on Unix-like systems, with int kept at 32 bits, while long, long long, and pointer types move to 64 bits. Typical ABIs in that family arrange for int to have size 4 with alignment 4, long, long long, pointer types, and double to have size 8 with alignment 8, and long double to occupy 16 bytes with alignment 16 on some targets. Windows on 64 bit uses LLP64, which keeps long at 4 bytes while giving pointers 8 bytes, yet still aligns pointers and 64 bit integers on 8 byte boundaries. These choices feed into struct layout, because the strictest alignment among the fields tends to dominate placement and trailing padding.

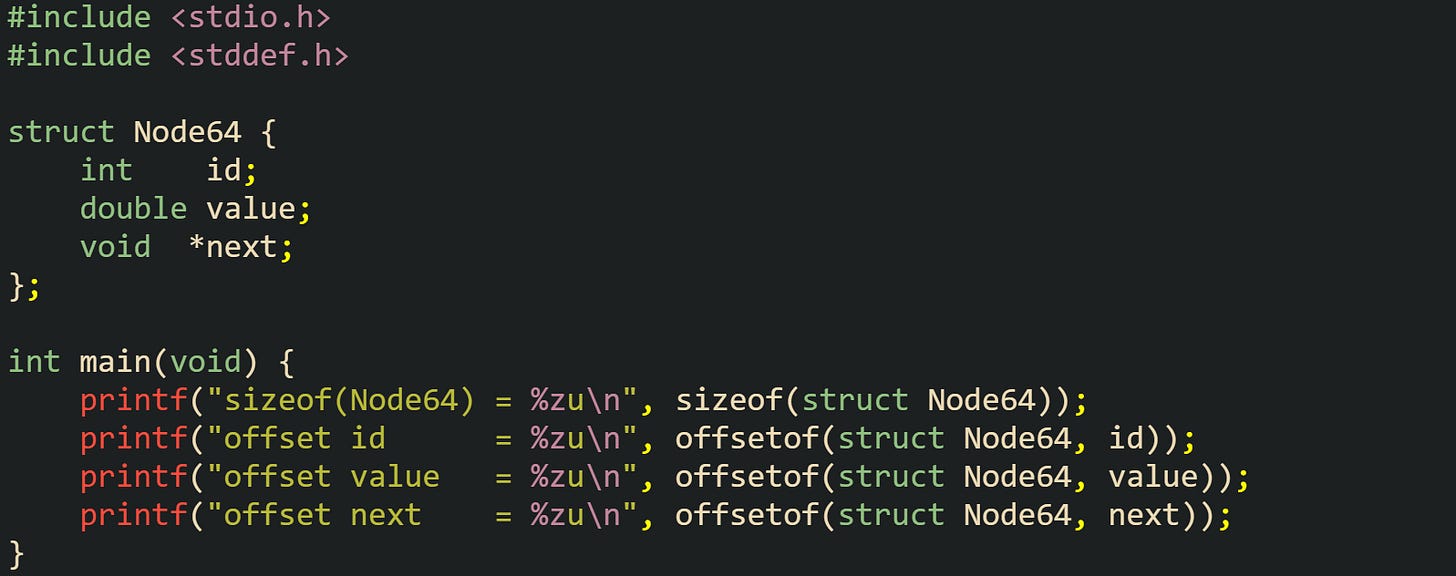

Let’s look at a struct that combines an int, a double, and a pointer that provides a direct view of these rules on a 64 bit build:

For a common 64 bit Linux target, id holds offset 0, the compiler then inserts padding so that value starts at an address divisible by 8, and next follows value, again at an address divisible by 8. The total size of Node64 usually lands on a multiple of 8 as well, so arrays of Node64 keep each element aligned for both the double and the pointer field. That layout leads to efficient loads and stores on processors that are tuned for naturally aligned 64 bit values, and also suits cache lines that carry multiples of 8 byte words.

Misaligned access rules on 64 bit hardware vary by architecture. x86_64 cores allow misaligned 64 bit and 128 bit loads and stores in most cases, yet extra cycles and split accesses across cache lines can still reduce throughput. Some other 64 bit architectures treat misaligned access as an error at the hardware level, and the operating system may emulate the access or terminate the process. Alignment rules inside structs help avoid those conditions by placing 64 bit fields at addresses that meet the documented constraints for the target.

A side effect of these choices is that sizeof for a given logical struct can grow when code moves from a 32 bit build to a 64 bit build, even when field types appear to be the same in source. Pointer fields expand from 4 to 8 bytes, alignment for those fields increases, and new padding appears so that every pointer and long field starts at an address with the correct multiple of 8. Cross-platform code that needs to match an external binary layout cannot assume that a 32 bit and a 64 bit build agree on sizeof for a struct that holds pointers or wide integers.

Struct Layout That Matches External Formats

Protocols and file formats tend to define byte layouts in strict terms, with specific field sizes, fixed offsets, and a single chosen byte order. That rigid layout does not always match the padding and alignment decisions a C compiler makes for a struct, so code that reads or writes binary data regularly needs more control than a plain struct definition provides.

One commonly used tool here is the set of fixed-width integer types from <stdint.h>. Types such as uint8_t, uint16_t, uint32_t, and uint64_t keep their widths across platforms that support them, so a struct that uses those types has predictable field sizes even when int or long differ between LP64 and LLP64 models. When a file format says that a field is a 32 bit unsigned integer, mapping that field to uint32_t keeps the C view aligned with the specification.

Network byte order raises a second concern, because many network protocols define their integers as big-endian values, while host systems can be little-endian or big-endian. C libraries on POSIX systems provide functions such as htons, htonl, ntohs, and ntohl in <arpa/inet.h> that convert between host order and network order. Application code can build packets in host byte order in ordinary structs and then convert individual fields when moving data into or out of a byte buffer that represents the network stream.

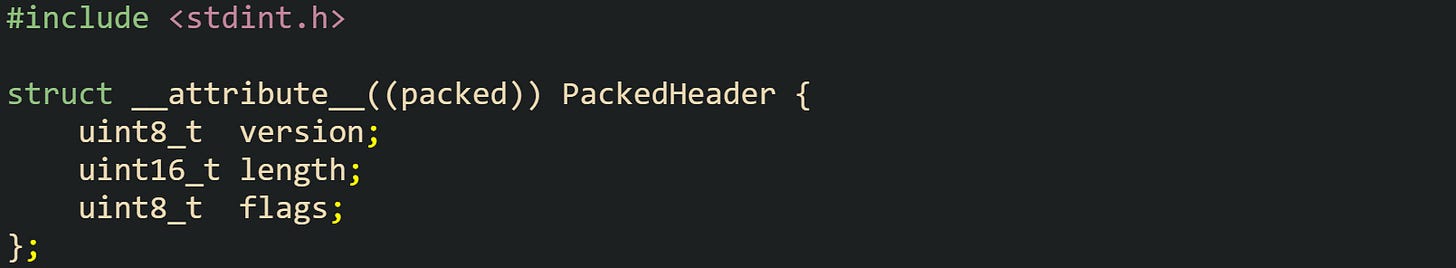

Packed structs give a third mechanism for matching exact external layouts. GCC and Clang support an attribute that requests one-byte alignment and no padding inside the struct:

That declaration asks the compiler to place version, length, and flags back to back with no insertion of extra bytes, so the memory representation of PackedHeader matches a packed header in a file or network message. Access to the length field may be slower on hardware that prefers aligned 16 bit values, and some architectures restrict direct misaligned access, so code frequently copies data from such packed structs into naturally aligned structs before heavy processing, then writes results back into packed form when sending or storing.

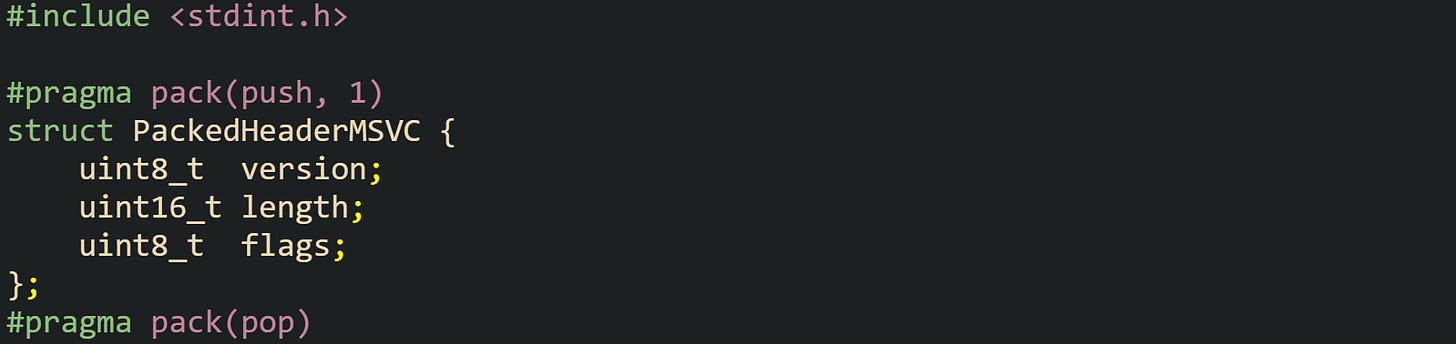

MSVC provides a related facility through #pragma pack, which adjusts alignment for the enclosed declarations:

That sequence of pragmas requests one-byte alignment for PackedHeaderMSVC and then restores the previous packing state. The fields still have the same sizes as on other targets, and the compiler refrains from inserting padding bytes, which leads to a header with the same byte layout as the GCC packed version.

Manual padding fields give a fourth technique that keeps more control in source. Code can add explicit filler arrays that occupy the padding bytes it wants, so that the first part of a struct matches a disk record format, while the full sizeof still reflects platform alignment rules:

In that struct the first 12 bytes form a stable prefix with two 32 bit integers, a status byte, and three unused bytes. A binary file format that states its header in that way can map directly to this struct prefix on any platform where uint32_t is a 32 bit unsigned type and byte order is compatible. Code that reads from disk can copy 12 header bytes into an instance of DiskRecord and then inspect id, timestamp, and status through field access, while leaving the padding array unused or reserved.

Alignment features from C11 and C23, such as _Alignas in older code and the alignas keyword in current revisions, also help when external formats or hardware units expect wider alignment than the natural one for the fields inside a struct. A struct that groups several uint32_t fields may still request 16 byte alignment at the struct level, so that each instance begins at a boundary accepted by a vector instruction set or by a hardware block cipher. Arrays of that struct then keep each element aligned for such units, while still providing field access through ordinary C expressions.

Conclusion

C structs tie language rules to the ABI, so alignment requirements and padding choices decide how fields sit in memory, what sizeof reports, and how arrays of those structs step through cache lines on 32 bit and 64 bit systems. The same rules that keep loads and stores aligned also explain why layouts change between platforms and why misaligned access can slow code or trigger faults on some hardware. When code has to match packets on the network or records on disk, fixed-width integer types, explicit alignment, packed attributes, and manual padding give enough control for C structs to match external formats while still relying on well defined mechanics for field order and representation.

![#include <stdio.h> #include <stdalign.h> struct Block { double x; double y; }; int main(void) { alignas(16) struct Block arr[4]; printf("sizeof(struct Block) = %zu\n", sizeof(struct Block)); printf("alignof(struct Block) = %zu\n", alignof(struct Block)); printf("address of arr[0] = %p\n", (void *)&arr[0]); } #include <stdio.h> #include <stdalign.h> struct Block { double x; double y; }; int main(void) { alignas(16) struct Block arr[4]; printf("sizeof(struct Block) = %zu\n", sizeof(struct Block)); printf("alignof(struct Block) = %zu\n", alignof(struct Block)); printf("address of arr[0] = %p\n", (void *)&arr[0]); }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Cp5z!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe70f17d2-ec73-4311-b857-4833c4e4aefa_1601x632.png)

![#include <stdint.h> struct DiskRecord { uint32_t id; uint32_t timestamp; uint8_t status; uint8_t pad[3]; /* pad to 12 bytes total */ }; #include <stdint.h> struct DiskRecord { uint32_t id; uint32_t timestamp; uint8_t status; uint8_t pad[3]; /* pad to 12 bytes total */ };](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lJ-G!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff4920dcf-8117-486f-8109-9c607e4ca14b_1606x336.png)

Really solid breakdown of alignment rules and their pratical impact. The comparison between 32-bit and 64-bit layouts made it click for me how moving to LP64 affects not just pointer sizes but everything downstream. I ran into this exact issue debugging a serialization bug where padding was inconsitent between builds. The packed struct examples are super helpful for anyone dealing with binary formats.