Command line tools written in C usually begin with a short word you type in a terminal plus a few extra arguments, and all of that text has to turn into integers, strings, flags, and file names inside main. The link between the command line and your C code is the function header int main(int argc, char *argv[]). That header decides how arguments arrive from the shell into your process, how they sit in memory as pointers through argc and argv, and how a return value from main goes back to the shell as an exit status that scripts can read.

How main Connects To The Shell

From the terminal side, a C tool looks like a command name and a set of words, yet several layers cooperate before control reaches main. The shell parses what you typed, the kernel creates a new process image, and the C runtime sets up standard data such as argc, argv, and the environment before handing control to your entry point.

Process Startup From The Shell

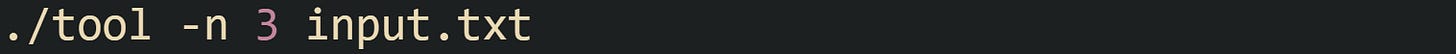

On a typical POSIX system, Let’s say you type something like:

In a shell leads to a call into the kernel through an execve family function. The shell already split that line into separate strings: "./tool", "-n", "3", and "input.txt". It then passes an array of pointers to those strings, plus a pointer to the environment strings, into execve.

From the C side this looks like a normal call to main, but there is a small startup routine in the C runtime that sits in between. That routine runs first in the fresh process image, receives the argument pointer array and its length from the kernel entry point, sets up the C environment, and finally calls your function with a header like:

All three headers are valid in a hosted C environment. The two forms with parameters are compatible, because char *argv[] and char **argv follow the same calling convention. The choice depends on whether the tool needs access to command line data. A utility that never looks at arguments can use int main(void) without argc and argv.

On POSIX systems, the low level entry point that the kernel jumps to is typically named _start or something similar in the C runtime. That code arranges argc, argv, and the environment pointer before calling main. After main returns, the same startup code calls exit with the return value, which sends an exit status back through the kernel to the shell.

Windows follows a similar chain but with a different interface. The operating system records a single command line string for the process, and the C runtime library splits that string into argc and argv before calling main. Some windows toolchains also support a wide character entry point:

The pointers in argv refer to wide character strings. That form appears when a project is built with wide entry points enabled and lets code handle Unicode command lines directly. From the point of view of C code, the structure is the same: a count of argument strings and an array of pointers to those strings.

Take this example where main is not called by your own code but by the runtime:

When you run ./tool a b c, the shell and runtime arrange that call so argc is 4 and argv holds the four expected entries. Nothing in your source triggers that call directly; the startup sequence between the kernel and the C library arranges it as part of process creation.

Layout Of argc argv In Memory

Inside main, the two parameters act like any other local variables in C. argc is an integer value. argv is a pointer to the first element of an array of char *. That array lives in memory reserved by the runtime before main runs, and every entry in the array points to a null terminated character sequence.

Conceptually, memory can be pictured like this at entry to main:

The first entry, argv[0], usually carries the name or path of the executable, matching what the user typed. Entries from argv[1] up to argv[argc - 1] point to argument strings. The final entry argv[argc] is required to be a null pointer, which gives library code a natural stopping point if it chooses to walk the array without argc.

The bytes that hold the actual text usually sit in a contiguous region of memory. All the argument strings live in that region one after another, and the array that argv points to holds the addresses into that region. That exact layout is an implementation detail and can differ between operating systems and runtimes, but some guarantees stay stable across them. argc is never negative, argv always points to an array with argc + 1 entries, every argv[i] where 0 <= i < argc points to a valid null terminated string, and argv[argc] is always null.

Now let’s take a look at a another example to help visualize how these pointers relate to memory addresses:

Running a compiled binary from this source with different arguments lets you see that argv itself is an address, and that every argv[i] is another address pointing into a region that holds characters. The actual numeric values are not important for logic, but looking at them shows that nothing mystical is happening; it is a regular array of pointers.

Environment variables sit nearby in many implementations. POSIX systems commonly expose an external variable:

That loop prints a few "NAME=value" strings from the environment. The C runtime usually arranges argv and environ close to each other when the process starts, though portable code should not rely on any specific relative order in memory.

Practical handling of arguments depends on the shell as well. When a user types ./tool hello world, most shells pass two separate strings "hello" and "world". When a user types ./tool "hello world", the shell passes one argument string with a space inside it. C code only sees the already split strings through argv and does not need to understand shell quoting rules to read them.

Practical Work With Command Line Data

Command line arguments turn into actual behavior only when code in main reads argc and argv and decides what to do with them. Some tools rely on fixed positions for input and output names, others prefer named flags such as -n or --output, and larger utilities lean on helper libraries so that argument parsing code stays reliable and readable. All of this still rests on those two parameters passed into main.

Manual Parsing Of Positional Arguments

Many small C utilities treat certain positions in argv as special. One position can hold an input file name, the next one can hold an output file name, and extra entries can be rejected as an error. That style keeps the interface short and very close to what the shell passes in.

Take this example with two file names:

That source checks the count before touching argv[1] or argv[2], so the tool never reads outside the array when someone forgets arguments. argv[0] holds a name that works nicely inside the usage message, because it matches what the person typed to start the process.

Numbers supplied on the command line arrive as text, so conversion functions come into play next. The standard library function strtol is common for this, partly because it can report where parsing stopped in the string and allows basic validation. You can build a small counter utility like this:

That branch on *argv[1] and *endptr makes sure that the string is not empty and that every character was part of the number. Values such as "123x" or "x10" cause an error path and a nonzero exit code instead of running with a half parsed value. The third argument to strtol sets the base, so 10 means decimal digits, while other values support octal or hexadecimal forms.

Some tools combine positional arguments with reasonable defaults to keep invocations shorter for common cases. It’s possible for a variant to accept an optional second argument and fall back to a default file name when that argument is missing. Take this for example:

That keeps argc checks near the top, then sets defaults and overrides in a controlled way. Positional arguments work well when there are only a few decision points and their meaning is obvious from context, such as an input and output pair.

Parsing Flags With getopt

Short flags allow more flexible command lines. A tool can accept -v to turn on extra output, -n 3 to set a count, or -o file.txt to redirect results. The POSIX getopt function processes such flags from argc and argv and keeps the remaining non option arguments grouped near the end.

On POSIX systems, getopt lives in <unistd.h>. It inspects argv sequentially and returns one option code at a time. When it encounters an option that takes a value, it stores a pointer to that value in the global variable optarg. It also updates optind, an index into argv that marks where flag processing left off.

This small file processing utility can be as simple as:

That flag string "vn:" tells getopt that -v is a bare flag and -n expects a value. When a user enters tool -v -n 5 input.txt, getopt first returns 'v', sets detail_mode, then returns 'n' with optarg pointing at "5", and finally returns -1 to mark the end of option parsing. optind then holds the index of "input.txt", so the loop over i treats everything from that point forward as non option arguments.

Short options can also be combined in a single group. A call like tool -vn5 input.txt yields the same effect on this code, with getopt walking through characters in "-vn5" and treating the final part as the value for -n. That gives users a compact way to stack flags while the parsing logic stays centralized in one loop.

Different flag sets call for different getopt strings. Suppose a networking tool takes -h for a host name and -p for a port, along with any number of extra strings that control commands. That utility can start like this:

Flag parsing logic stays close to the top of main, which makes the interface easy to see when reading the source. getopt also supports some variations such as treating + or leading colons in the option string as markers for different error handling styles, though many tools stay with the basic form shown here.

getopt is part of the POSIX standard and is widely available on Unix like platforms. On Windows, some toolchains ship a compatible implementation, while others may require a separate library if the same flag handling style is desired.

argp Support With Exit Status

The GNU C library provides the argp interface, which sits a bit higher level than getopt. Instead of manually looping over result codes, the developer fills out tables of options and writes a callback that receives one event at a time. The library then prints help text, handles --help and --version, and forms error messages in a consistent way.

Here is a short argp based utility:

This code defines one option, -n or --count, stores the requested line count in a global variable, and uses argp_error to print an error and exit when the value is missing or not positive. Help text for --help comes from the option table and the argp structure, including the "Line counter" string passed in the initializer.

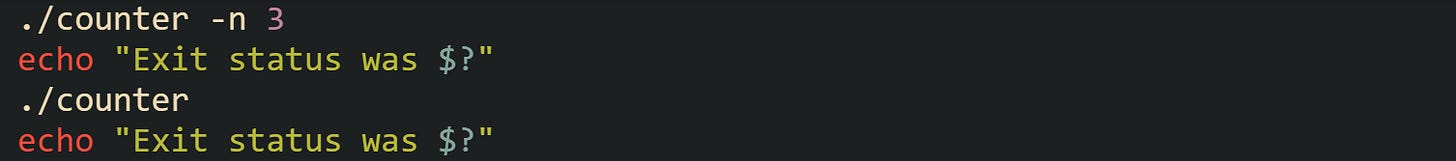

Exit status connects C tools back to shells and scripts. return from main provides an integer that the runtime passes to the kernel as the process status. On POSIX shells, the special variable $? holds this status for the most recent command. Take this short shell session for example:

The first run prints three lines and leaves $? set to 0. The second run triggers a usage error inside argp_error, and $? holds a nonzero value that the shell can test.

Windows command shells use %ERRORLEVEL% to report process status, while PowerShell prefers $LASTEXITCODE. C code compiled with a Windows C runtime still returns from main with an integer, and the runtime passes that value back as the process exit code. Scripts in those environments can branch on those variables much like POSIX shells do with $?.

These exit codes let small C tools fit naturally into larger command chains. Shell scripts or batch files can run a tool, read its status, and either continue normal work or print a diagnostic and stop, all driven by the integer returned from main or passed to exit.

Conclusion

Most of what you type into a shell flows through the same few building blocks in C, from the runtime handing argc and argv into main, to those pointers reaching argument strings in memory, then on to your own logic that turns them into file names, flags, and numeric exit codes that shells and scripts can react to. Manual positional parsing, short options handled by getopt, and higher level helpers such as argp all rest on the same foundation of an integer count, an array of pointers to null terminated strings, and a single status value returned from main that reports how the process finished.

![int main(void); int main(int argc, char *argv[]); int main(int argc, char **argv); int main(void); int main(int argc, char *argv[]); int main(int argc, char **argv);](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!kVWe!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3e127a41-5ed4-44a2-a49c-44ea60ce2f61_1703x170.png)

![int wmain(int argc, wchar_t *argv[]); int wmain(int argc, wchar_t *argv[]);](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Hh5U!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F61468c79-4dda-4704-a0d2-483770e0acfb_1738x55.png)

![#include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { printf("Started with %d arguments\n", argc); return 0; } #include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { printf("Started with %d arguments\n", argc); return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!gsDA!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F02b593a2-d031-4499-9249-99706b171482_1740x336.png)

![argv argv[0] -> "./tool\0" argv[1] -> "-n\0" argv[2] -> "3\0" argv[3] -> "input.txt\0" argv[4] -> NULL argv argv[0] -> "./tool\0" argv[1] -> "-n\0" argv[2] -> "3\0" argv[3] -> "input.txt\0" argv[4] -> NULL](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!w6jC!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F75bcfaa3-200a-4c25-93a0-8924e1c53e89_1544x338.png)

![#include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { printf("Address stored in argv = %p\n", (void *)argv); for (int i = 0; i < argc; i++) { printf("argv[%d] at %p holds \"%s\"\n", i, (void *)argv[i], argv[i]); } return 0; } #include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { printf("Address stored in argv = %p\n", (void *)argv); for (int i = 0; i < argc; i++) { printf("argv[%d] at %p holds \"%s\"\n", i, (void *)argv[i], argv[i]); } return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!kNs8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7a1d0b29-c562-4eb3-9084-b2e3017a9f99_1695x561.png)

![#include <stdio.h> extern char **environ; int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { (void)argc; /* suppress unused parameter warning */ for (int i = 0; environ[i] != NULL && i < 5; i++) { printf("environ[%d] = %s\n", i, environ[i]); } return 0; } #include <stdio.h> extern char **environ; int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { (void)argc; /* suppress unused parameter warning */ for (int i = 0; environ[i] != NULL && i < 5; i++) { printf("environ[%d] = %s\n", i, environ[i]); } return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!JiC8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcc48f00d-d828-4625-a9db-64836f5c5525_1699x674.png)

![#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { if (argc != 3) { fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s input_file output_file\n", argv[0]); return 1; } const char *input_file = argv[1]; const char *output_file = argv[2]; printf("Reading from %s\n", input_file); printf("Writing to %s\n", output_file); /* actual processing would go here */ return 0; } #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { if (argc != 3) { fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s input_file output_file\n", argv[0]); return 1; } const char *input_file = argv[1]; const char *output_file = argv[2]; printf("Reading from %s\n", input_file); printf("Writing to %s\n", output_file); /* actual processing would go here */ return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ko36!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd710bd0a-041b-41d5-b325-378b538f70a4_1497x802.png)

![#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { if (argc != 2) { fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s count\n", argv[0]); return 1; } char *endptr = NULL; long count = strtol(argv[1], &endptr, 10); if (*argv[1] == '\0' || *endptr != '\0') { fprintf(stderr, "Invalid integer value: %s\n", argv[1]); return 2; } printf("Count is %ld\n", count); /* work based on count would go here */ return 0; } #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { if (argc != 2) { fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s count\n", argv[0]); return 1; } char *endptr = NULL; long count = strtol(argv[1], &endptr, 10); if (*argv[1] == '\0' || *endptr != '\0') { fprintf(stderr, "Invalid integer value: %s\n", argv[1]); return 2; } printf("Count is %ld\n", count); /* work based on count would go here */ return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!MONv!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F02968517-a5ab-48c9-a007-b5dc8eefceda_1491x924.png)

![#include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { const char *input_file = NULL; const char *output_file = "output.txt"; if (argc < 2) { fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s input_file [output_file]\n", argv[0]); return 1; } input_file = argv[1]; if (argc >= 3) { output_file = argv[2]; } printf("Input = %s\n", input_file); printf("Output = %s\n", output_file); return 0; } #include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { const char *input_file = NULL; const char *output_file = "output.txt"; if (argc < 2) { fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s input_file [output_file]\n", argv[0]); return 1; } input_file = argv[1]; if (argc >= 3) { output_file = argv[2]; } printf("Input = %s\n", input_file); printf("Output = %s\n", output_file); return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!-cFh!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4b3fbe89-9c83-404d-af0b-7939c89c6399_1495x923.png)

![#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <unistd.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { int detail_mode = 0; long count = 1; int opt; while ((opt = getopt(argc, argv, "vn:")) != -1) { switch (opt) { case 'v': detail_mode = 1; break; case 'n': count = strtol(optarg, NULL, 10); break; default: fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s [-v] [-n count] file...\n", argv[0]); return 1; } } if (optind >= argc) { fprintf(stderr, "Missing file argument\n"); return 2; } if (detail_mode) { printf("Count = %ld\n", count); } for (int i = optind; i < argc; i++) { printf("Processing %s\n", argv[i]); } return 0; } #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <unistd.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { int detail_mode = 0; long count = 1; int opt; while ((opt = getopt(argc, argv, "vn:")) != -1) { switch (opt) { case 'v': detail_mode = 1; break; case 'n': count = strtol(optarg, NULL, 10); break; default: fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s [-v] [-n count] file...\n", argv[0]); return 1; } } if (optind >= argc) { fprintf(stderr, "Missing file argument\n"); return 2; } if (detail_mode) { printf("Count = %ld\n", count); } for (int i = optind; i < argc; i++) { printf("Processing %s\n", argv[i]); } return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!R_aC!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F24cc3f60-8c42-4190-92c5-2f6e7ccc88aa_1799x1066.png)

![#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <unistd.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { const char *host = "localhost"; int port = 0; int opt; while ((opt = getopt(argc, argv, "h:p:")) != -1) { switch (opt) { case 'h': host = optarg; break; case 'p': port = atoi(optarg); break; default: fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s [-h host] -p port cmd...\n", argv[0]); return 1; } } if (port == 0) { fprintf(stderr, "Port is required\n"); return 2; } printf("Connecting to %s on port %d\n", host, port); for (int i = optind; i < argc; i++) { printf("Command argument %d: %s\n", i - optind + 1, argv[i]); } return 0; } #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <unistd.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { const char *host = "localhost"; int port = 0; int opt; while ((opt = getopt(argc, argv, "h:p:")) != -1) { switch (opt) { case 'h': host = optarg; break; case 'p': port = atoi(optarg); break; default: fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s [-h host] -p port cmd...\n", argv[0]); return 1; } } if (port == 0) { fprintf(stderr, "Port is required\n"); return 2; } printf("Connecting to %s on port %d\n", host, port); for (int i = optind; i < argc; i++) { printf("Command argument %d: %s\n", i - optind + 1, argv[i]); } return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!E3Ya!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fff94cd2c-53a0-45aa-93db-d918170761cf_1789x1040.png)

![#include <argp.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> static struct argp_option options[] = { { "count", 'n', "N", 0, "Lines to print" }, { 0 } }; static long count = 0; static error_t parse_opt(int key, char *arg, struct argp_state *state) { switch (key) { case 'n': count = strtol(arg, NULL, 10); return 0; case ARGP_KEY_END: if (count <= 0) { argp_error(state, "-n N must be positive"); } return 0; default: return ARGP_ERR_UNKNOWN; } } static struct argp argp = { options, parse_opt, 0, "Line counter" }; int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { argp_parse(&argp, argc, argv, 0, 0, NULL); for (long i = 0; i < count; i++) { printf("%ld\n", i + 1); } return 0; } #include <argp.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> static struct argp_option options[] = { { "count", 'n', "N", 0, "Lines to print" }, { 0 } }; static long count = 0; static error_t parse_opt(int key, char *arg, struct argp_state *state) { switch (key) { case 'n': count = strtol(arg, NULL, 10); return 0; case ARGP_KEY_END: if (count <= 0) { argp_error(state, "-n N must be positive"); } return 0; default: return ARGP_ERR_UNKNOWN; } } static struct argp argp = { options, parse_opt, 0, "Line counter" }; int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { argp_parse(&argp, argc, argv, 0, 0, NULL); for (long i = 0; i < count; i++) { printf("%ld\n", i + 1); } return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!92hK!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa21ca7d3-ab04-4df8-b7b1-2527a86d6cea_1801x1039.png)