Removing records gets more involved when one table connects to another. You can’t delete whatever you want without thinking about how those rows are tied together. If a row in one table points to another and you remove it without care, the database will block you. When the goal is to delete based on something found in a different table, a JOIN helps make that possible. What we’re covering here is how that works behind the scenes, how the engine checks for matches, and what makes the delete safe without breaking foreign key links.

Why Deletes Involving a Join Need Special Care

You can’t just remove rows without thinking about how they relate to other parts of the database. If one table depends on another and you delete something that breaks that link, the database steps in and stops it. That protection comes from constraints, and they exist to make sure everything lines up the way it should. So when the goal is to delete based on something found in a different table, a regular delete isn’t always enough. We’re walking through how that works, what the database engine checks for behind the scenes, and how it applies the delete in a way that keeps things valid.

Foreign Keys Make Deletes a Bit Different

A foreign key is a column that connects one table to another. It holds values that are expected to match something in a different table, and the database checks that relationship every time data changes.

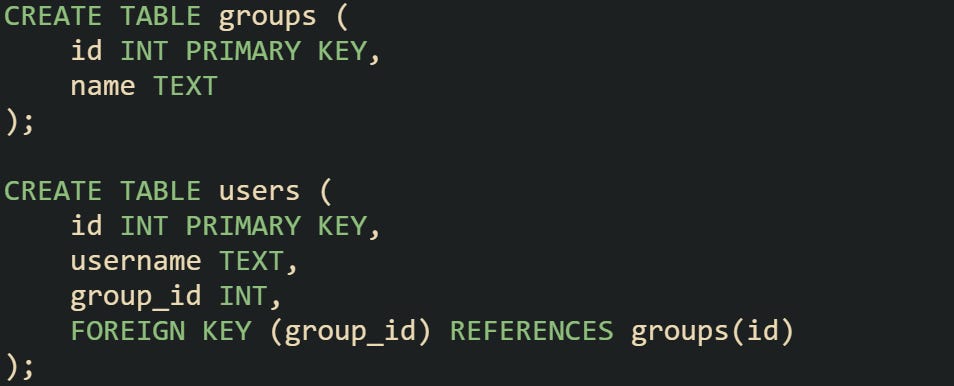

Let’s say you have a pair of tables where users belong to groups. Each user row has a group_id, and that value points to a row in the groups table. If that group gets removed while users still point to it, the database sees that as a broken reference and won’t allow it.

Try to delete the group with id = 3 while user rows still include group_id = 3, and you’ll hit an error. The only way through is to either remove the users first or have the database delete them automatically by setting up cascading behavior. If neither one is in place, the query fails. That’s what makes delete queries a little more involved when relationships are in play. You have to think about what else depends on the row you’re trying to remove. If you don’t, the constraints stop the operation, and nothing gets removed.

What A Join Does Before The Delete

When a delete query includes a join, the database builds a temporary result just for that moment. Nothing gets stored. It’s used as a way to figure out what matches and what can be safely deleted. The join works the same way it would in a select query. It lines up rows across tables based on a match. The difference is that instead of returning rows for display, it deletes rows from one table if the match holds true.

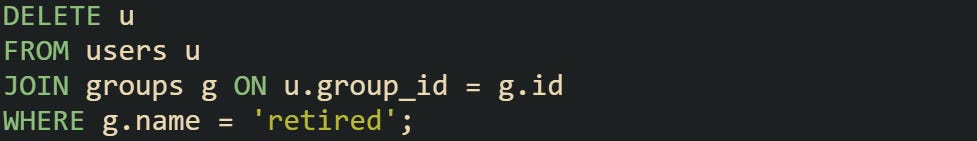

Here’s a case where you want to delete users who belong to a group labeled as retired.

The engine walks through both tables, finds all rows where the group_id matches and the group name is 'retired', and then deletes only those user rows. The groups table stays untouched. It’s there only to help match the right users.

What happens in the background depends on which database you’re using, but most will apply locks to the matching rows and read from indexes if they’re available. Then they move forward with the delete only after checking all constraints. That temporary join result disappears once the query finishes.

Why It Matters Which Table You Delete From

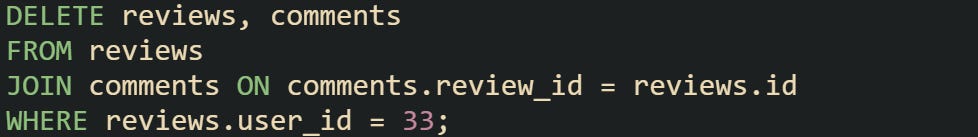

Most engines limit a join-delete to one target table, but MySQL and MariaDB let you list several targets:

This removes the matching rows from both reviews and comments. If you only need to clear the parent table while still using comments to drive the match, list a single target instead:

It helps to be very clear about which table the delete is actually working on. The database won’t always warn you if your logic is pointing at the wrong thing. And if you use short aliases like u and g, it gets easy to forget which one is active.

Here’s another variation where the delete focuses on groups instead of users:

This time the users table is just helping the match. The delete happens on the groups. That only works if no other rows depend on those group IDs. If they do, the database rejects the query unless you’ve already told it to cascade those deletes down.

The planner figures all of this out before anything actually happens. It checks how to match the rows, runs through the rules for constraints, and decides whether the delete can proceed. That gives you a safety net, but only if the query itself makes sense. It’s up to you to write the match in a way that reflects the structure of the data.

How to Write Safe Delete Queries With a Join

Deleting rows with a join means being specific and clear about what stays and what goes. When multiple tables are part of the logic, the database needs to keep the connections between them intact. That includes checking constraints, applying filters, and making sure nothing is removed that breaks the way the data fits together. Different systems have their own way of handling these queries, but the goal remains the same across all of them. The delete should only touch rows that match exactly what you meant to target, nothing more.

Writing Delete Queries That Use Joins

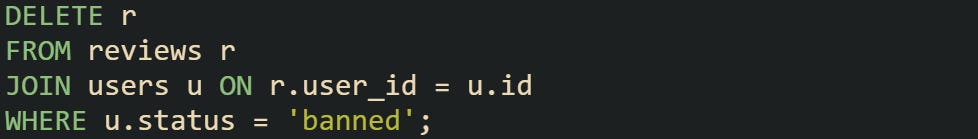

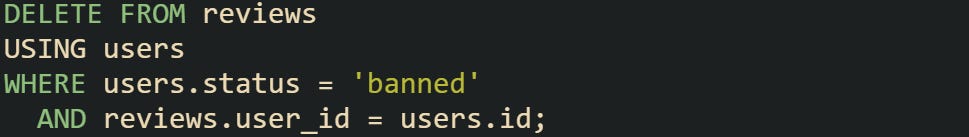

Every database engine handles this a little differently. They all support deleting with a condition that compares across tables, but the way the syntax is structured depends on which one you’re working with. In MySQL and MariaDB, the format is direct and easy to follow. You say which table you’re deleting from, join it to another, and then add the condition. Here’s a query that removes reviews written by users who have been flagged as banned.

This query lines up reviews with users, finds the ones where the user has been banned, and removes just the reviews. The user table helps define the match but isn’t affected.

In SQL Server the same statement runs unchanged, so one block covers both platforms. The engine lines up reviews with users, checks the status, and removes just the matched review rows.

PostgreSQL lets you join another table inside a DELETE by using the USING clause. It works just like a join-delete in MySQL or SQL Server, only the keyword is USING instead of JOIN.

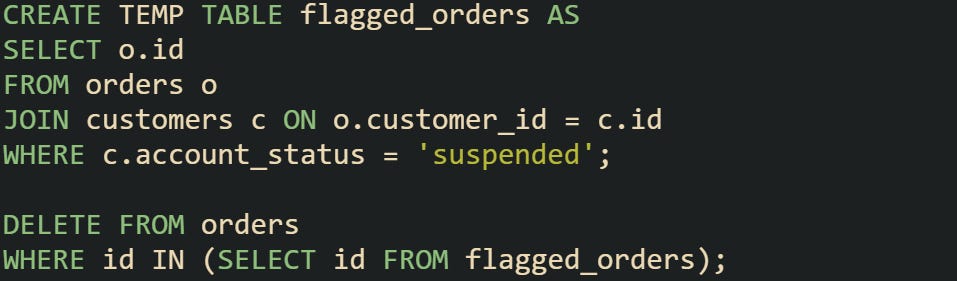

The planner treats the USING clause as a temporary join that's only there for the current query. It lines up the two tables in memory and removes the rows from the one listed directly after the word DELETE. The join works the same way as in a SELECT, but the database just drops the matching rows instead of returning them. If you’re stuck on a PostgreSQL release earlier than 8.1, which came out before the USING option was added, go with an IN or EXISTS filter instead. Temporary tables are another option when the logic is too long or when you want more control before running the delete. Here’s a case where orders need to be deleted if the linked customer account is suspended.

The temp table holds the IDs from the match, and then the delete works only on those rows. This helps when the main delete would be too complex or when you want to test the match separately.

Avoiding Mistakes That Affect More Rows Than You Expected

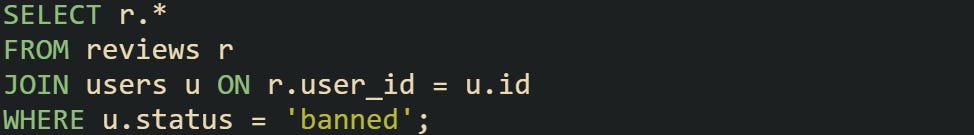

The fastest way to lose control of a delete is to forget what it’s really selecting. It can still be valid SQL even if it deletes far more than you meant. The easiest way to stay safe is to run the join as a select first and make sure the match is doing exactly what you want.

If the result looks right, then you can trust that switching SELECT to DELETE will work as expected. If you see more rows than you intended, or if the query returns nothing at all, it’s a sign that something in the condition needs adjusting.

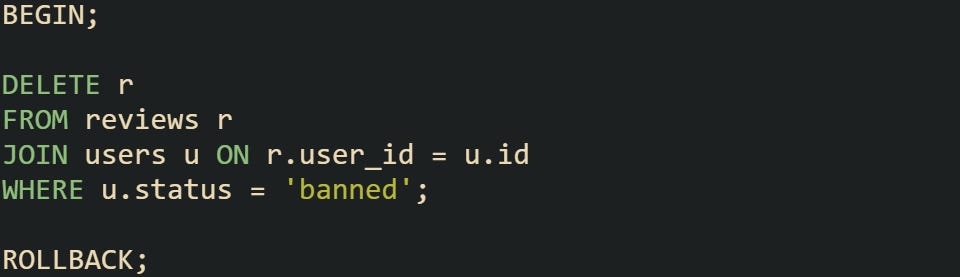

Another helpful move is to use transactions during testing. This lets you try the delete, check how many rows it affected, and then undo it if the number looks off.

You can inspect what happened, and only re-run the delete without the rollback when you’re ready to keep the changes. This gives you more control without committing right away.

Short aliases can also lead to mistakes. It’s easy to forget which table you’re deleting from, especially when several are joined together. Always check that the alias after DELETE points to the right one. If it doesn’t, the database won't warn you unless a constraint stops the query.

What Happens When the Delete Runs

Before anything is removed, the query planner builds a list of steps that describe how the join will be carried out. That includes how the tables are scanned, how rows are matched, and how filters are applied. When the plan is complete, the delete goes row by row through the match list and applies the removal. If indexes exist on the join columns or the filter columns, the planner reads fewer rows. That makes the process quicker and reduces the amount of locking that happens during execution. Without indexes, the planner reads through both tables and filters later, which takes more time and uses more resources.

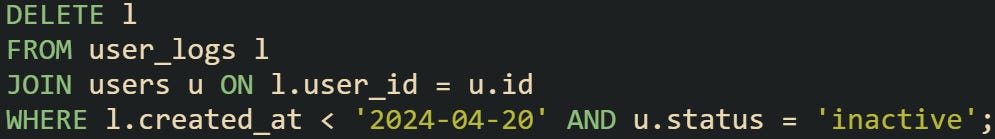

Take this case where user logs are removed based on a cutoff date, but only for inactive users.

If created_at and status are indexed, the engine can jump directly to the relevant rows. If not, it has to scan both tables and build the match from scratch. That means longer execution and possibly longer locks if many rows are touched. During the delete, the database checks constraints before each row is removed. It checks for triggers, for foreign keys, and for any dependent data. If one of those checks fails, the row doesn’t get deleted and the query stops.

This process keeps your data safe, but it only works if the delete query matches the real structure of the tables involved. If you’ve matched the rows correctly and the constraints support it, the delete goes through without issue.

When Direct Join Deletes Aren’t Supported

Some databases don’t support joins in a delete directly. In those cases, you still have ways to get the same result by writing the logic in steps.

Here’s how you can remove sessions for users who haven’t logged in in over a year.

Or using an EXISTS clause to do the match row by row:

Both queries work without needing a join inside the delete. They still let you match based on other tables and delete rows based on those matches. They just shift the logic into the filter step instead of the join itself.

If a direct join delete doesn’t work in your environment, splitting it out like this gives you the same control. It takes a little more typing, but it works in any system that allows basic subqueries.

Conclusion

Deleting rows with a join works by building a match between tables, filtering down the results, and then removing only from the one you’ve specified. The database engine lines everything up through its planner, checks the constraints, and walks through the matches step by step. If the logic fits the structure of the data, the delete runs without trouble. You can write it as a join, a subquery, or a temporary match, but the process still depends on how that match is formed and how the engine follows it.