Dynamic allocation lets C code request memory while it runs instead of relying only on fixed-size arrays or stack variables. That extra flexibility comes from a group of library calls that talk to a heap allocator inside the C runtime. These calls hand out blocks of bytes, track their sizes internally, and expect the caller to return those blocks when they are no longer needed. If that protocol is broken, bugs such as leaks, double frees, and use-after-free errors appear and can be very hard to debug. The mechanics behind malloc, calloc, realloc, and free explain how these blocks are requested, resized, and released, and how those mistakes arise in everyday C code.

Heap Allocation Basics

Dynamic memory in C adds a third storage area next to the call stack and the static data segment. Local variables on the stack work well for short lifetimes, and static objects remain in memory for the entire run of the process, but sometimes code needs storage that survives a function return without staying around forever. Heap allocation fills that gap. Calls to malloc, calloc, or realloc ask a runtime allocator to carve out blocks of bytes from a managed region of memory, and later calls to free hand those blocks back. The allocator keeps extra bytes of metadata near each block so it can track size and availability, while C code only sees a pointer to the first usable byte.

Heap Storage Versus Automatic Storage

Code written in C relies on several storage durations that behave differently when functions call each other and return.

Automatic storage applies to most variables declared inside functions without the static keyword. Compilers typically place those variables on a call stack, reserving space when the function starts and releasing that space when it returns. Any pointer that still refers to that stack memory after the function ends is no longer valid, even if the numeric address has not changed.

Static storage covers objects with file scope and objects declared with static inside functions. Those objects live from before main runs until the process exits. Pointers to such objects remain valid for that entire period. Memory for these objects usually sits in a fixed region managed by the loader and runtime, not by the heap allocator.

Heap storage behaves differently because lifetimes are controlled directly by calls to the allocator. Successful calls to malloc or calloc return pointers that stay valid until the code passes the same pointers to free or to realloc in a way that releases the blocks. Those pointers can be copied, stored in structures, or passed across many function boundaries, and the allocator does not reclaim the blocks until free sees them.

The contrast between stack storage and heap storage shows up when a function wants to give its caller access to data that outlives the function. Pointers to local arrays on the stack become invalid as soon as the function returns, while pointers to blocks from malloc stay valid until they are freed. The two functions below show that contrast in practice:

print_stack_message uses automatic storage for msg, which works because all access happens before the function returns. Function make_heap_message allocates msg on the heap and returns a pointer, so callers can keep that pointer beyond the function boundary and still have valid storage, as long as they eventually call free on the returned value.

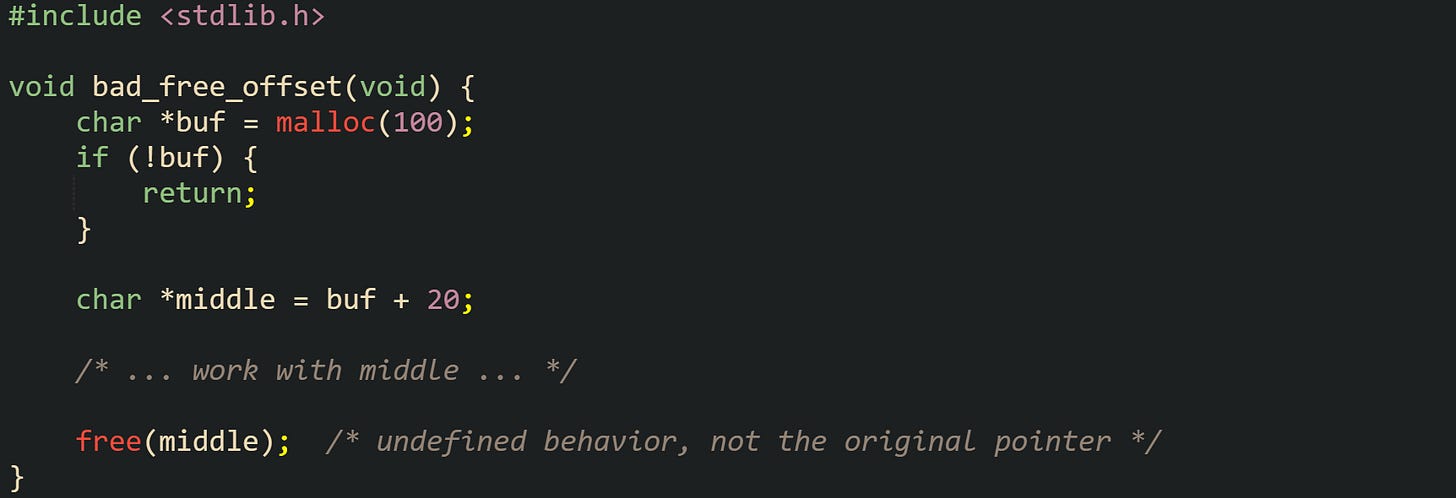

Returning a pointer to stack storage breaks lifetime rules, and compilers cannot reliably stop that mistake at compile time:

Pointer p holds an address from the stack frame used by bad_pointer, but that frame no longer belongs to the caller. Any later stack activity can reuse that slot, and reading through p triggers undefined behavior. Heap storage avoids this problem by separating object lifetime from call depth.

Static objects also interact with heap pointers. A static pointer can hold a heap address for as long as the process runs, and the data behind that pointer only goes away if free is called.

Here static storage holds the pointer rather than the integers themselves. The integers live on the heap between init_numbers and release_numbers, and shared_numbers keeps track of their address across calls.

Allocation Functions

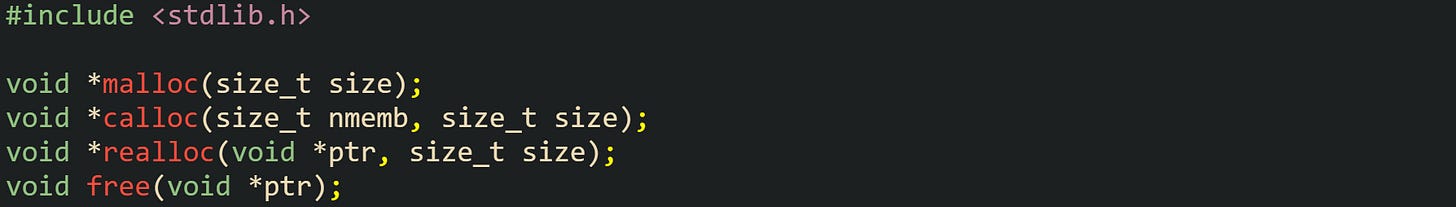

The four standard allocation functions in <stdlib.h> form the central interface to the heap. They share the same size type, size_t, and all except free return void *, so the caller can convert the pointer to any object type that fits in the block. Their prototypes look like this:

The function malloc requests a specific number of bytes. The allocator searches its internal data structures for a free block large enough for that request, possibly splits a larger free block, or extends the heap if needed. The return value is either a pointer to at least that many bytes of uninitialized storage or NULL on failure. Bytes in the new block have indeterminate values until the code writes to them.

Many compilers and libraries allocate slightly more than requested and use part of that extra space to track the size and status of each block. That metadata stays hidden from ordinary C code, which only sees the pointer handed back.

Function calloc behaves like malloc with two important differences. It takes an element count nmemb and an element size size, allocates space for nmemb objects of size bytes each, and sets all bits in the allocated block to zero. If the mathematical product nmemb * size is not representable as a value of type size_t, calloc returns NULL. This behavior works well when code wants an array of integers that all start at zero.

Take this example that uses calloc to allocate and print an array of integers:

Each element prints as zero because calloc has already set every byte in the block to zero. On typical two’s complement machines without unusual padding bits, that bit pattern corresponds to the integer value zero for each array element.

Function realloc adjusts the size of an existing allocation. When growing an allocation, the allocator first checks if there is free space directly after the current block. If enough space is available, the block can be expanded in place. If not, a new block is allocated, data from the old block is copied up to the smaller of the old and new sizes, the old block is freed, and the new address is returned. Shrinking a block can leave extra space that the allocator marks as available for future allocations.

This code grows an array of integers with realloc:

The variable values always holds the active pointer for the array. Temporary pointer tmp receives the result of realloc, and only after checking for NULL does the code overwrite values. If realloc returns NULL while new_count is nonzero, the original block is still valid and must be freed before the function returns.

Function free releases a block so the allocator can reuse its storage. The call has defined behavior only when ptr is either NULL or a value previously returned by malloc, calloc, realloc, or aligned_alloc that has not yet been freed. Calling free on anything else, or calling it twice on the same allocation, produces undefined behavior. Passing NULL is always allowed and has no effect.

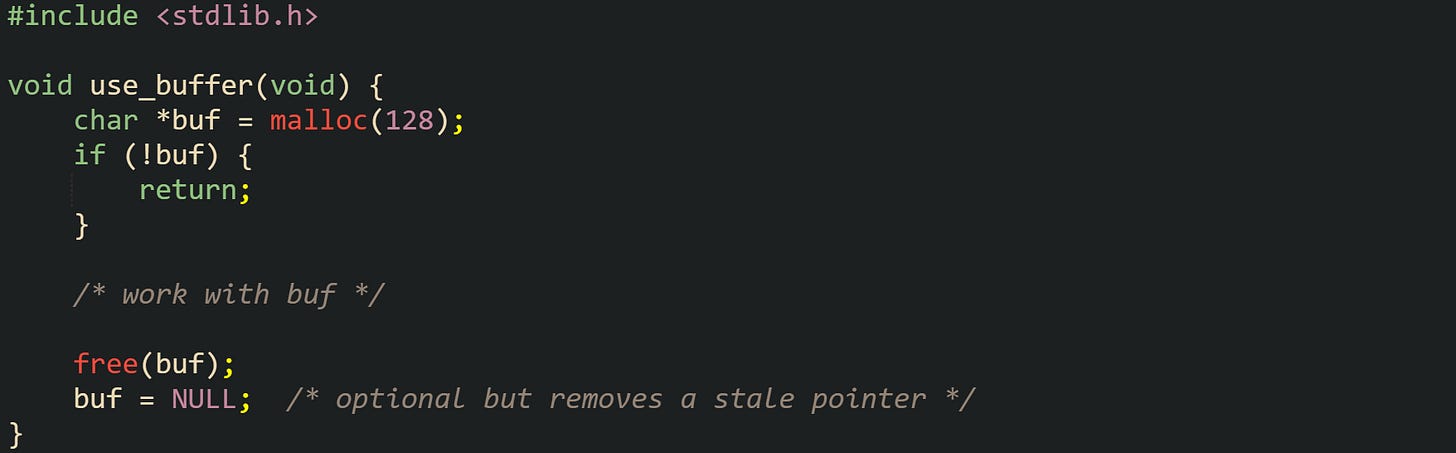

This helper allocates a buffer, works with it, then releases it:

Setting buf to NULL after free does not change allocator behavior, but it removes a stale address from the variable and turns any later free(buf) call into a harmless no-op.

Modern C standards also add aligned_alloc for situations where extra alignment is required. This function takes an alignment value and a size and returns a block whose address is a multiple of the alignment, subject to restrictions such as the size being a multiple of that alignment. Many projects still rely entirely on the basic four functions, because standard malloc already meets the needs of most types.

Alignment With Pointer Types

Heap allocators must return pointers that satisfy alignment requirements for the object types stored in their blocks. Alignment means that addresses for objects of a given type follow certain boundaries in memory, so hardware can access them efficiently. On mainstream C implementations, malloc returns a pointer that is suitably aligned for any object type with fundamental alignment, including standard arithmetic types and pointer types.

Misaligned pointers can cause slower access or even hardware faults on some architectures. Heap allocation shields callers from most of those concerns by always returning pointers that meet alignment constraints for these common types.

Now let’s see an example that allocates an array of structures on the heap:

Pointer p refers to storage that the allocator has aligned for struct sample. The compiler can assume that p[0].x sits at an address suitable for double, and p[0].y sits at an address suitable for int, without any extra work from the caller.

The C standard defines a type named max_align_t whose alignment is at least as strict as that of any scalar type with fundamental alignment, and requires that malloc return pointers aligned suitably for that type. Any block large enough to store a single max_align_t object can also store any int, double, or pointer without violating alignment constraints.

Some specialized data structures, such as those that depend on cache line alignment or vector instruction alignment, need addresses that go beyond the guarantees of malloc. For those situations, aligned_alloc in C11 and later provides aligned storage when the requested size follows the rules laid out by the standard, and several platforms also offer posix_memalign or vendor-specific allocation functions. When that level of control is not required, standard malloc is sufficient for ordinary scalar types and structures built from them.

Heap Memory Errors

Heap allocation breaks the tight link between object lifetime and stack frames, which opens the door to bugs that never arise with plain local variables. Blocks obtained from malloc, calloc, or realloc can outlive the functions that created them, move when resized, and disappear only when the allocator sees a matching free call. When code loses track of a pointer, calls free multiple times, or accesses memory after it has been released, the allocator’s internal view of the heap no longer matches what the surrounding code expects. That mismatch turns into leaks, random crashes, and data corruption that can be hard to track down without tools.

Memory Leaks In C Code

Leak bugs occur when a block from malloc, calloc, or realloc is still marked as in use by the allocator, but every reachable pointer in the process has stopped referring to it. The bytes remain reserved inside the heap, yet no part of the code can hand that block back to free. Long-running services and utilities that allocate inside loops feel this problem strongly, because each lost block accumulates in the heap and never returns to the allocator’s free lists.

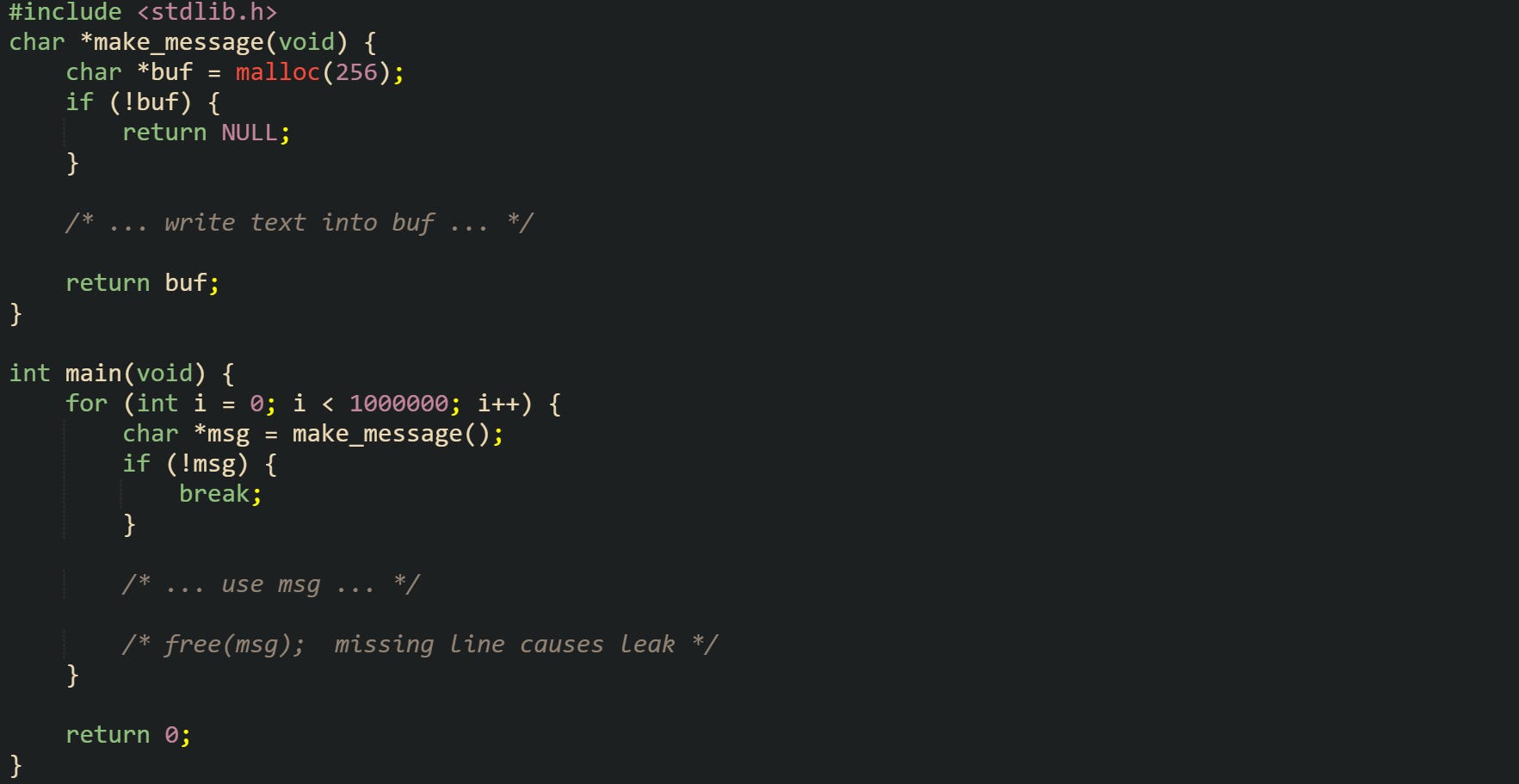

One common leak grows out of a helper that allocates memory, returns a pointer, and leaves it up to the caller to free that pointer. If the caller forgets to free it on every control-flow branch, the allocator keeps losing blocks. Take this code with a leak that accumulates in a loop:

Control flow looks very ordinary, but each loop iteration allocates a fresh 256 byte block and never frees it. The local pointer msg goes out of scope at the end of the loop body, so the process loses its only handle on that memory. After a lot of iterations, total heap usage climbs by large amounts, and the allocator still treats every one of those blocks as active.

Error handling contributes to leaks in a similar way. Functions that allocate several objects and return early on failure must release everything allocated so far, or callers inherit the leak silently. The next code block has two separate allocations with matching free calls on error:

This code guards against leaks by freeing everything that has been allocated when a later step fails. Leaving out the matching free calls on those early returns would leave heap blocks stranded whenever allocation of name or scores fails.

Global or static pointers can hide leaks too. Processes that allocate memory into a global array and never free it before exit still leak, although in many environments the operating system reclaims all memory when the process finishes. Long-lived daemons, servers, and tools that run for days do not get that safety net during their lifetime. Their leak profile depends on how carefully they balance allocations with calls to free.

Tools like valgrind on Linux, the address sanitizer in modern compilers, and platform specific leak detectors watch allocations and deallocations and report any blocks still reachable only from internal allocator structures at process exit. Those tools also record stack traces at the point of allocation, which gives a direct route back to the parts of the code that lost the pointers.

Invalid Free Operations

Heap allocators expect very specific values in calls to free and realloc. Errors start when code passes pointers that do not match blocks under allocator control. Double frees, use after free, freeing stack addresses, and freeing pointers into the middle of allocations all fall in this category. Each one violates allocator assumptions and leads to undefined behavior.

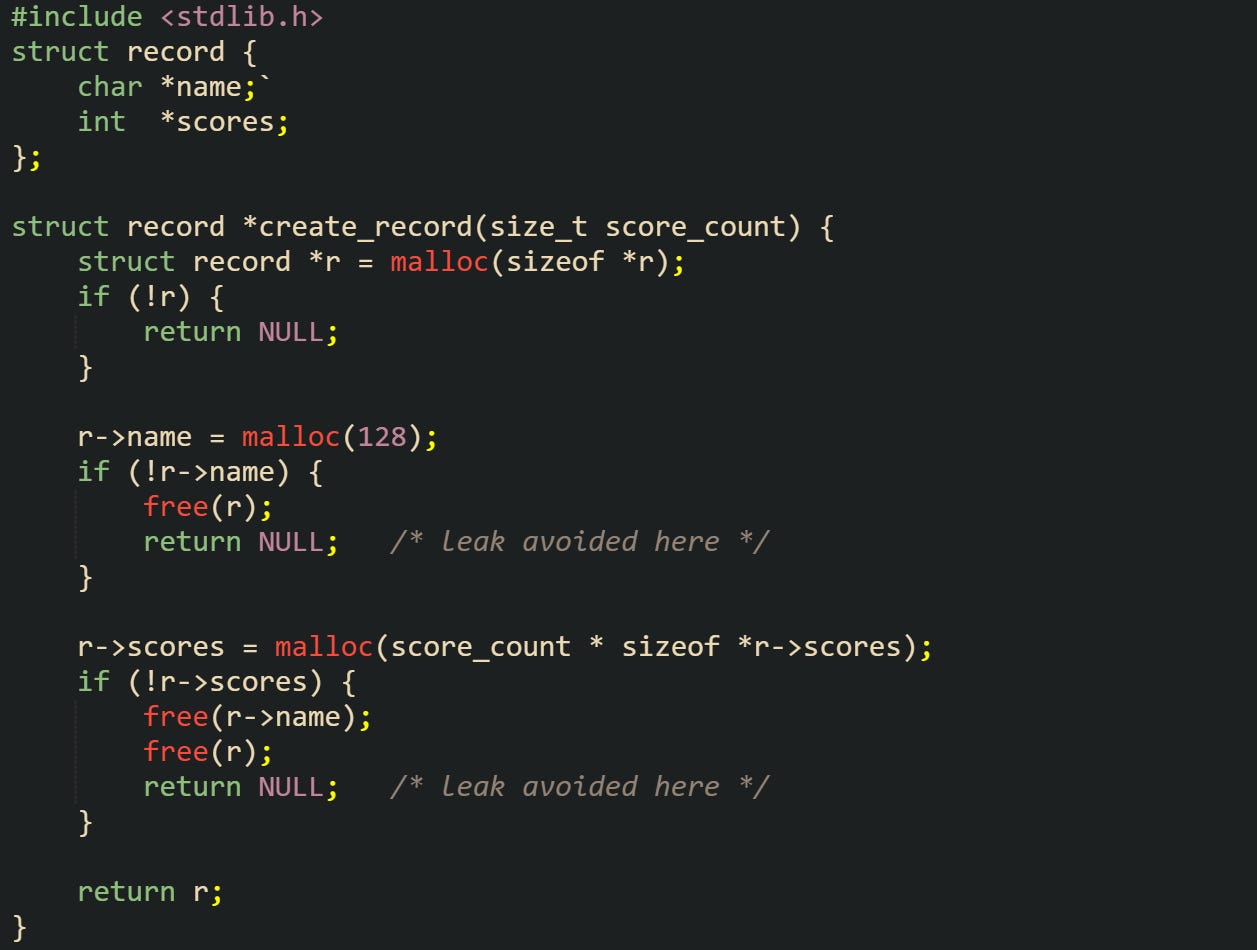

Double free bugs arise when a block that has already been released is passed to free a second time. Plenty of current allocators detect this with runtime checks and abort the process, but there is no guarantee of friendly behavior. Now let’s look at a block that has a minimal double free:

The first free(data) call hands the block back to the allocator. Internal metadata changes to mark the block as available. The second free(data) call passes a pointer that no longer belongs to an active allocation. Allocator code that trusts its own state more than caller input can walk corrupted lists or reuse the same block in two places, leading to very hard to diagnose memory problems.

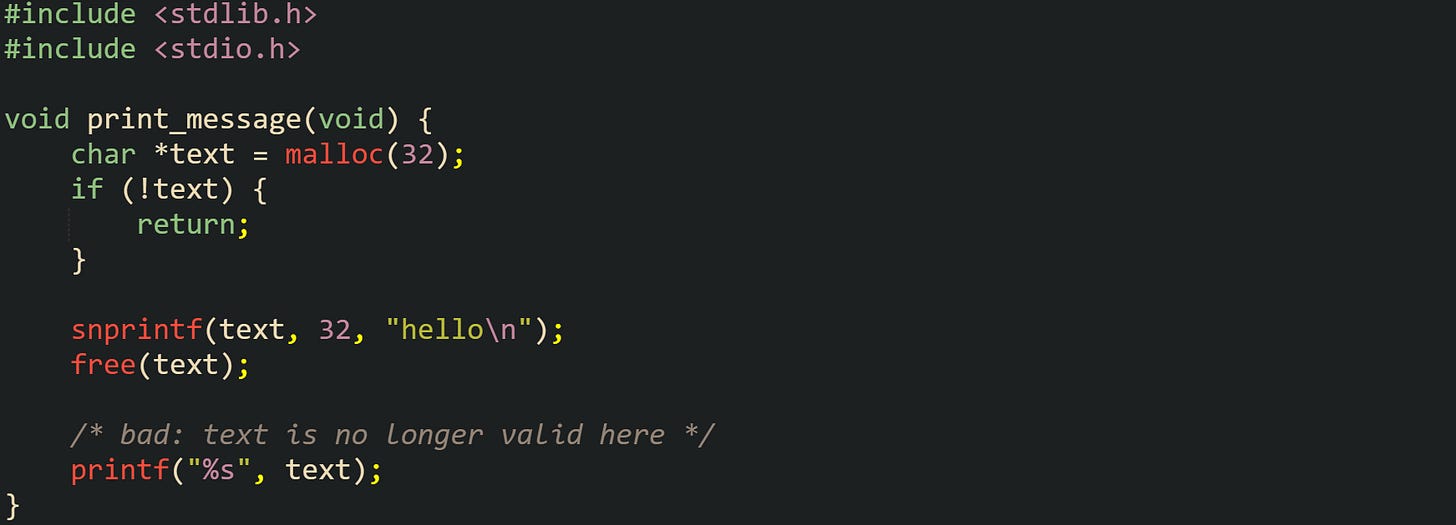

Use after free bugs take a different route. The allocator accepts a call to free, marks the block as no longer in use, and any later access to that memory through old pointers touches storage that may already hold unrelated data. This next example pairs a write and a read with a call to free in between:

Callers sometimes see this function print the expected text, which can give the illusion that nothing is wrong. If the allocator has not yet reused that block, old contents still sit there. Under heavier load, or with different allocator settings, the same call sequence tends to crash, print garbage, or interact badly with other heap activity. Address sanitizers are very good at catching this class of bugs, because they keep shadow metadata that marks freed regions and watch pointers that point into those regions.

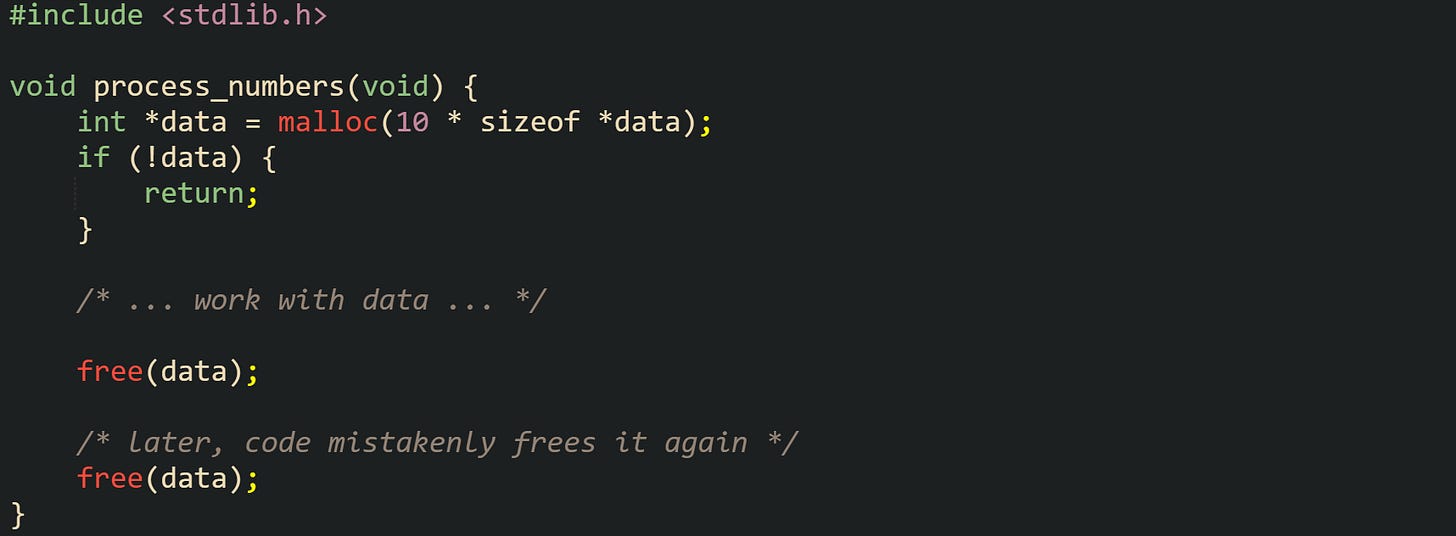

Calls to realloc add a further source of invalid access. When realloc grows a block, it can either keep the block in place or move it to a new location. Old pointer values no longer refer to valid storage when a move happens. For example, take this function that has this sequence and then continues to use the old pointer:

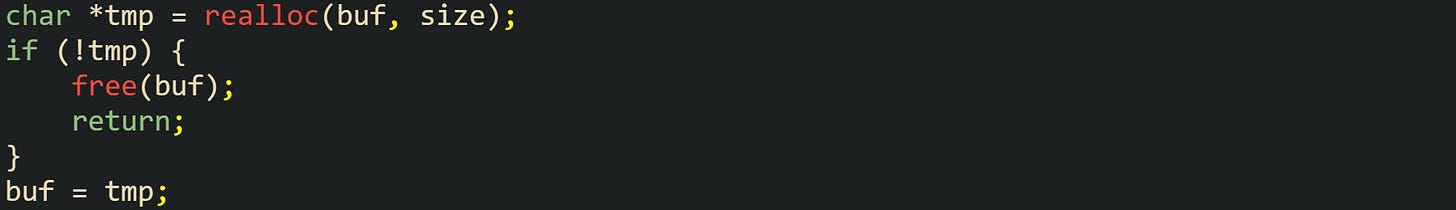

Correct code treats the return value from realloc as the single valid pointer for that block from that point forward. This safer idiom keeps the old pointer in a temporary until success is confirmed, then updates the original variable. This next code has that form:

After that assignment, all future accesses go through buf, which holds either the old address or the new one, depending on how the allocator handled the request.

Freeing memory that never came from malloc and friends is a frequent source of failures. Passing the address of a stack variable or a global object to free leaves the allocator staring at bytes that were never registered as a block. In many implementations, that pointer value ends up being interpreted as a header for a heap block, which leads to immediate corruption of internal lists or trees. Let’s now see a code block that has this mistake with a stack variable:

Pointer p refers to memory on the stack, owned by the current function frame, not to a heap allocation. Passing it to free gives the allocator data that has nothing to do with its block structures.

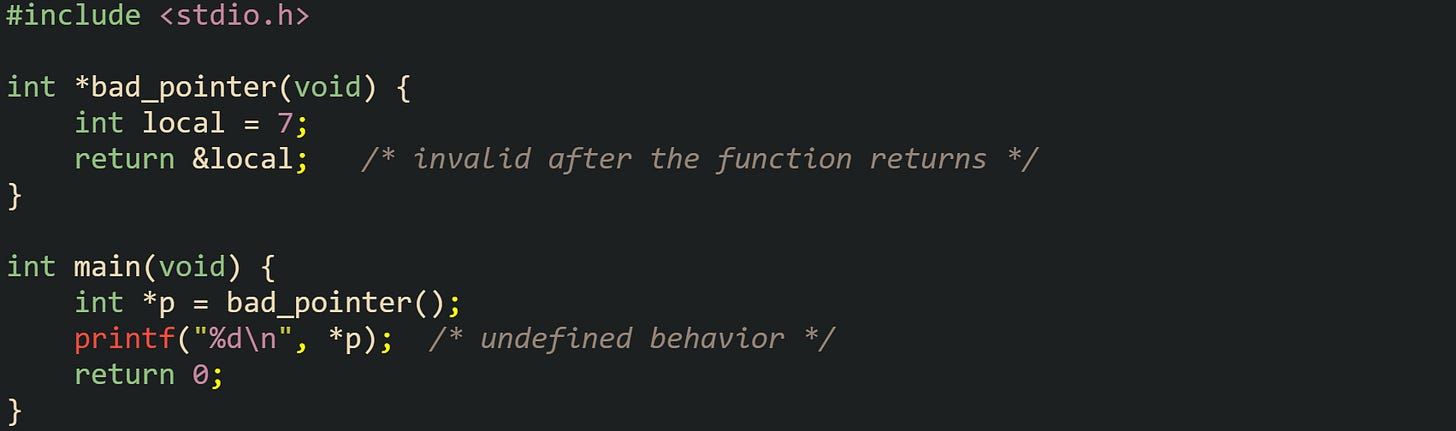

There is also a class of bugs where code passes a pointer into the middle of a valid block rather than the original pointer. The allocator expects the address it handed out, not some interior address. Any arithmetic that offsets the pointer needs to be undone before free is called.

Allocator internals rarely tolerate such input. Internal header placement, guard regions, and free list structures all depend on clients returning exactly the addresses they received.

Practical defenses against these errors include setting pointers to NULL after freeing, avoiding shared ownership of heap pointers between unrelated parts of the code, and relying on tools such as address sanitizers, valgrind, and platform specific analyzers during testing. Those tools track allocations, deallocations, and accesses in parallel with the compiled code and report misuse of heap memory with stack traces that point back to the offending functions.

Conclusion

Dynamic memory in C rests on a small group of functions that manage the heap like malloc, calloc, realloc, and free, and all of the mechanics come from how those calls hand blocks out and take them back. The allocator tracks sizes and lifetimes, while code requests the right number of bytes, holds the returned pointers carefully, and matches each successful allocation with a single free at the right moment. The same rules that let heap blocks support arrays, structures, and buffers that outlive a single stack frame also explain how leaks, double frees, and use after free errors arise when a pointer is lost or misused. Keeping that flow in mind while reading and writing C can help you reason about where bytes come from, how long they stay valid, and when they leave the process again.

![#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> char *make_heap_message(void) { char *msg = malloc(32); if (!msg) { return NULL; } snprintf(msg, 32, "Hello from heap\n"); return msg; } void print_stack_message(void) { char msg[32] = "Hello from stack\n"; printf("%s", msg); } #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> char *make_heap_message(void) { char *msg = malloc(32); if (!msg) { return NULL; } snprintf(msg, 32, "Hello from heap\n"); return msg; } void print_stack_message(void) { char msg[32] = "Hello from stack\n"; printf("%s", msg); }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!JPho!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1ecd18fd-01a7-46e1-80ac-a4d2d1d02aa1_1737x712.png)

![#include <stdlib.h> static int *shared_numbers; void init_numbers(void) { shared_numbers = malloc(5 * sizeof *shared_numbers); if (!shared_numbers) { return; } for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { shared_numbers[i] = i * 2; } } void release_numbers(void) { free(shared_numbers); shared_numbers = NULL; } #include <stdlib.h> static int *shared_numbers; void init_numbers(void) { shared_numbers = malloc(5 * sizeof *shared_numbers); if (!shared_numbers) { return; } for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { shared_numbers[i] = i * 2; } } void release_numbers(void) { free(shared_numbers); shared_numbers = NULL; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!5b2g!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6de79d5c-8b02-4052-b56f-a2646beb1d0e_1732x796.png)

![#include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(void) { size_t count = 4; int *values = calloc(count, sizeof *values); if (!values) { perror("calloc"); return 1; } for (size_t i = 0; i < count; i++) { printf("%d\n", values[i]); /* prints 0 each time */ } free(values); return 0; } #include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(void) { size_t count = 4; int *values = calloc(count, sizeof *values); if (!values) { perror("calloc"); return 1; } for (size_t i = 0; i < count; i++) { printf("%d\n", values[i]); /* prints 0 each time */ } free(values); return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!qUSE!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffa316c0c-2908-46b6-a323-05a62ca84f3b_1740x757.png)

![#include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(void) { size_t count = 2; int *values = malloc(count * sizeof *values); if (!values) { perror("malloc"); return 1; } values[0] = 10; values[1] = 20; size_t new_count = 4; int *tmp = realloc(values, new_count * sizeof *values); if (!tmp) { free(values); perror("realloc"); return 1; } values = tmp; values[2] = 30; values[3] = 40; for (size_t i = 0; i < new_count; i++) { printf("%d\n", values[i]); } free(values); return 0; } #include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(void) { size_t count = 2; int *values = malloc(count * sizeof *values); if (!values) { perror("malloc"); return 1; } values[0] = 10; values[1] = 20; size_t new_count = 4; int *tmp = realloc(values, new_count * sizeof *values); if (!tmp) { free(values); perror("realloc"); return 1; } values = tmp; values[2] = 30; values[3] = 40; for (size_t i = 0; i < new_count; i++) { printf("%d\n", values[i]); } free(values); return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!JZ4v!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F94e37c58-f71c-4e00-ab9f-3f3c1c4f38e4_1793x923.png)

![#include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> struct sample { double x; int y; }; int main(void) { struct sample *p = malloc(3 * sizeof *p); if (!p) { perror("malloc"); return 1; } p[0].x = 1.5; p[0].y = 7; printf("%f %d\n", p[0].x, p[0].y); free(p); return 0; } #include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> struct sample { double x; int y; }; int main(void) { struct sample *p = malloc(3 * sizeof *p); if (!p) { perror("malloc"); return 1; } p[0].x = 1.5; p[0].y = 7; printf("%f %d\n", p[0].x, p[0].y); free(p); return 0; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!G5QI!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0a824001-f70e-40be-bbb4-adca8c54bbac_1782x808.png)

![#include <stdlib.h> void grow_buffer(void) { size_t size = 16; char *buf = malloc(size); if (!buf) { return; } /* ... write data ... */ size = 32; char *new_buf = realloc(buf, size); if (!new_buf) { free(buf); return; } /* bad: buf is used after realloc */ buf[0] = 'X'; /* buf may now be invalid */ new_buf[1] = 'Y'; } #include <stdlib.h> void grow_buffer(void) { size_t size = 16; char *buf = malloc(size); if (!buf) { return; } /* ... write data ... */ size = 32; char *new_buf = realloc(buf, size); if (!new_buf) { free(buf); return; } /* bad: buf is used after realloc */ buf[0] = 'X'; /* buf may now be invalid */ new_buf[1] = 'Y'; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!-fLV!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb859c9f9-8980-49d4-86ea-b394615a7184_1760x770.png)