Error reporting in C code feels pretty low level compared to many higher level languages. Instead of exceptions, C code relies on function return values and a shared error indicator called errno. That pair controls how libraries announce problems, how applications detect them, and how error messages reach logs or a terminal. When you see how return codes, errno, and helper functions like perror and strerror interact, you get a practical model for writing C code that catches problems early and passes accurate information up the call chain.

Return Codes From C Functions

C code relies on return values to tell the caller how a function call went. Instead of throwing exceptions, a function indicates success, partial work, or failure through a numeric or pointer result. Library writers pick a convention for each function, and callers read that result immediately to decide what to do next. After some practice, you can look at a function prototype and infer how it reports problems in normal use.

Return values matter even for small helper functions. Missing a check can mean writing to a closed file, treating an empty buffer as valid data, or ignoring a partial write to a socket. Error handling in C starts with recognizing which values indicate success and which ones indicate trouble.

Status Values From Standard Library

It is common for standard library functions that acquire some resource to follow a common rule where a non null pointer means success and NULL means failure, and that holds for calls like fopen, malloc, and other functions that allocate memory or open handles.

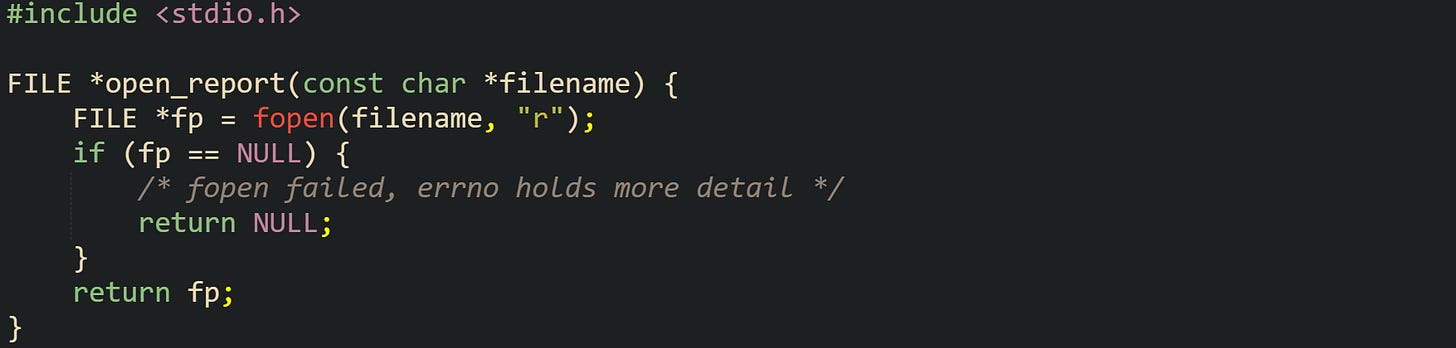

Now let’s take a look at a basic file open helper to see this in action:

That helper wraps fopen and passes its success or failure back to the caller through the FILE * return value. Any caller that receives NULL has an obvious sign that no stream is available and should not try to read or write.

Memory allocation follows the same idea. This helper keeps that rule in one place:

This function can be used to centralize allocation for a component. Code that calls allocate_buffer checks for NULL right away and can log or return an error status to higher layers when no memory is available.

Functions that process buffered I O, such as fread and fwrite, use size based return values instead of pointers. fread returns the number of complete objects read into memory. If that value is smaller than the requested count, the call either reached end of file or saw an error. The only way to tell which case happened is to call feof and ferror. fwrite behaves in a similar way but reports how many objects were written.

Character level functions from <stdio.h> use special markers for errors and end of file. fgetc returns an unsigned char value converted to int on success and EOF on failure or end of file. EOF is usually -1. getc and getchar share the same convention.

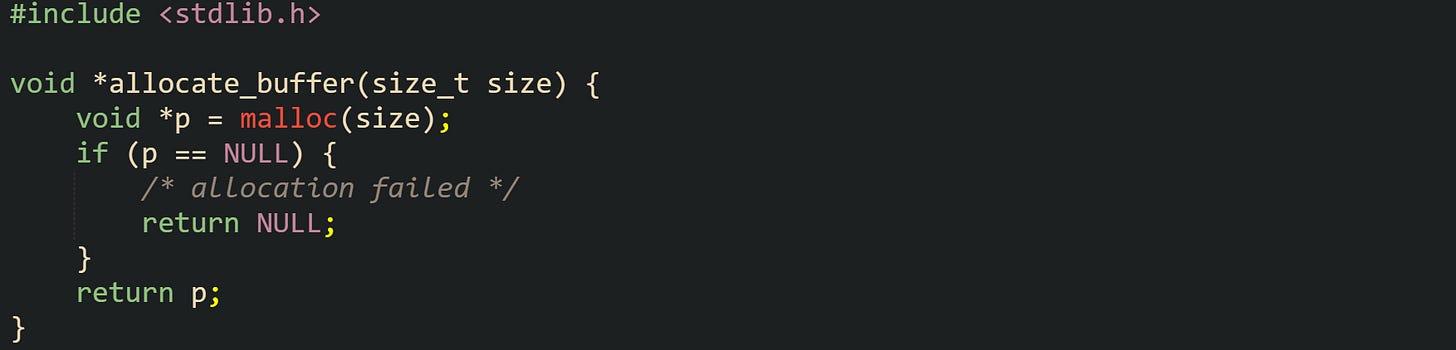

Take this example helper that reads a configuration character and makes use of that convention:

This helper reads one character and then maps the three possible outcomes into different results. Callers can treat -1 as a read failure, -2 as end of file, and any other value as a valid character.

Different parts of the standard library settle on different status conventions, but they tend to share two ideas. Special pointer values such as NULL signal failure for pointer returns, and numeric functions pick one or more special values to indicate errors or special conditions. The documentation for each function spells out those values, and the caller is responsible for checking them right away.

Interpreting Negative Results

System level I O on Unix like platforms uses file descriptors and the type ssize_t for many calls. Functions such as read, write, and send return a signed size that tells you how much work completed. Positive values represent counts, zero has a special meaning, and negative values mark errors.

The classic example is read:

In that code, the function reads characters one by one until it sees a newline, runs out of space, hits end of file, or reports an error. Three different return ranges from read control that loop. Negative values leave the helper with -1 to flag the error, zero marks end of file, and a positive value means a character arrived and can go into the buffer.

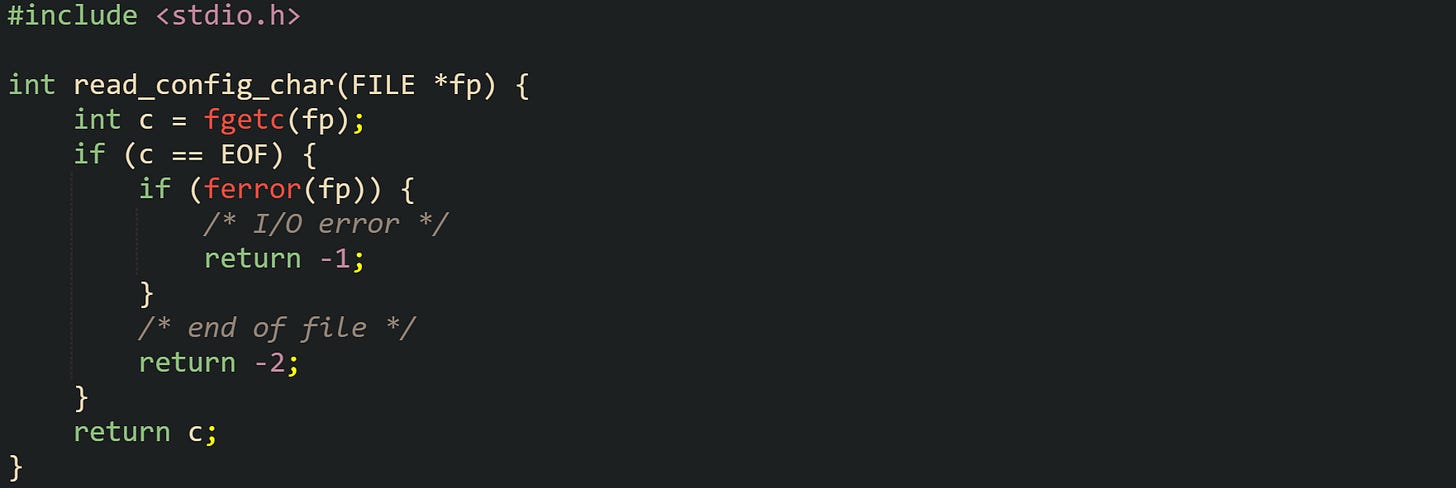

write has a very similar contract but focused on sending bytes instead of reading them. It can write fewer bytes than requested even when nothing went wrong, so code that needs to send an exact amount in one go must loop until all bytes leave the buffer or an error occurs.

This helper keeps calling write until all bytes are sent or a problem stops progress. Negative values pass an error back to the caller, and positive values reduce the number of bytes left.

Many other POSIX calls use the same signed size convention. Socket functions such as send and recv, as well as I O functions for pipes and terminals, all return ssize_t and use negative values for errors. That shared rule makes it easier for C code to handle different I O sources through the same helper functions.

Common Return Code Checks

Practical error handling in C depends on checking return values immediately and keeping that logic close to the call that can fail. Waiting several lines or several function calls before inspecting a status value can leave code in a state where it already tried to use a bad pointer or an invalid descriptor.

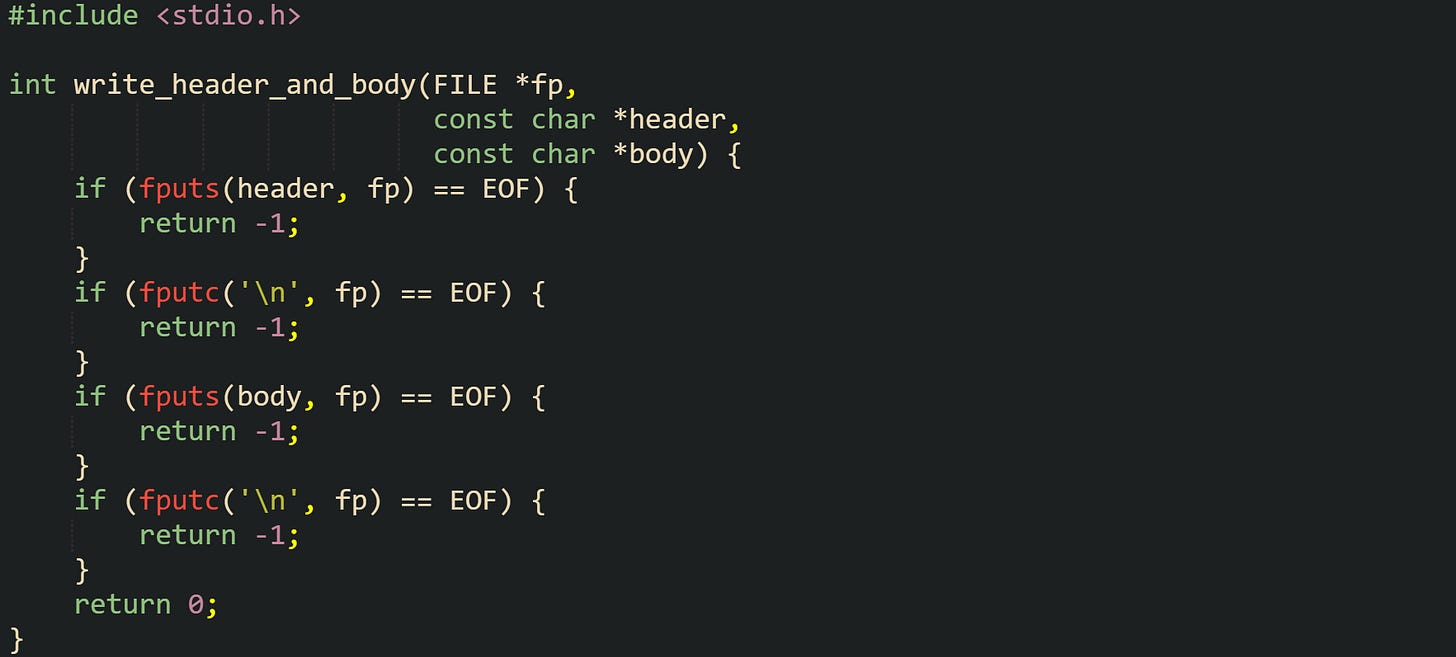

Short helpers make these checks easier to write and easier to review. Callers that want to write one record to a file can delegate the detailed return value handling to a helper and only read a single status from that helper.

For this function, it treats any failure from fputs or fputc as a failure for the entire record write. Higher level functions can pass that status up to their callers without repeating the low level checks.

When several operations share one resource, such as a stream or a socket, it is common to collect their return values into a single status code. That way, the caller can test one result instead of many separate flags.

With this routine, it treats the header and body as a single unit. Any failure in the sequence returns -1. Nothing fancy happens here, but the structure is predictable, and the caller can handle success or failure with a single if statement.

Return code checks also interact with resource release. When a function opens a file, allocates memory, and then writes data, it should release those resources if a later step fails. Common practice is to jump to a final label and return a single status at the end of the helper, so that every exit branch frees what needs to be freed and reports the same kind of status to callers.

errno Based Error Reporting

Libraries in C, and many POSIX calls rely on a shared error indicator named errno so callers can learn why a function failed. Return values tell you that a problem happened, while errno holds a numeric code that points to the specific reason. That combination makes it possible to distinguish missing files from permission problems, memory exhaustion from invalid arguments, and many other cases that would look the same if you only checked a return code.

The symbol errno lives in <errno.h> and behaves like a global integer, but modern implementations arrange it so that each thread has its own copy. Thread local storage keeps error information separate for concurrent threads, while the source code still reads and writes errno as if it were a single variable. That detail matters in multi threaded C, because one thread should not overwrite an error that belongs to another.

Functions that follow this convention set errno to a positive error number when they fail. Callers read errno right after a call reports an error through its return value and ignore it after successful calls.

How errno Is Set

The header <errno.h> defines errno as a macro that refers to a modifiable int. That macro usually expands to an expression that reads or writes memory that belongs to the current thread. Code that runs in a single thread can treat it as a simple global integer, while threaded code still gets one error slot per thread.

Portable code does not assume that library functions reset errno on success or leave it unchanged. It treats errno as relevant only after a function reports failure through its return value.

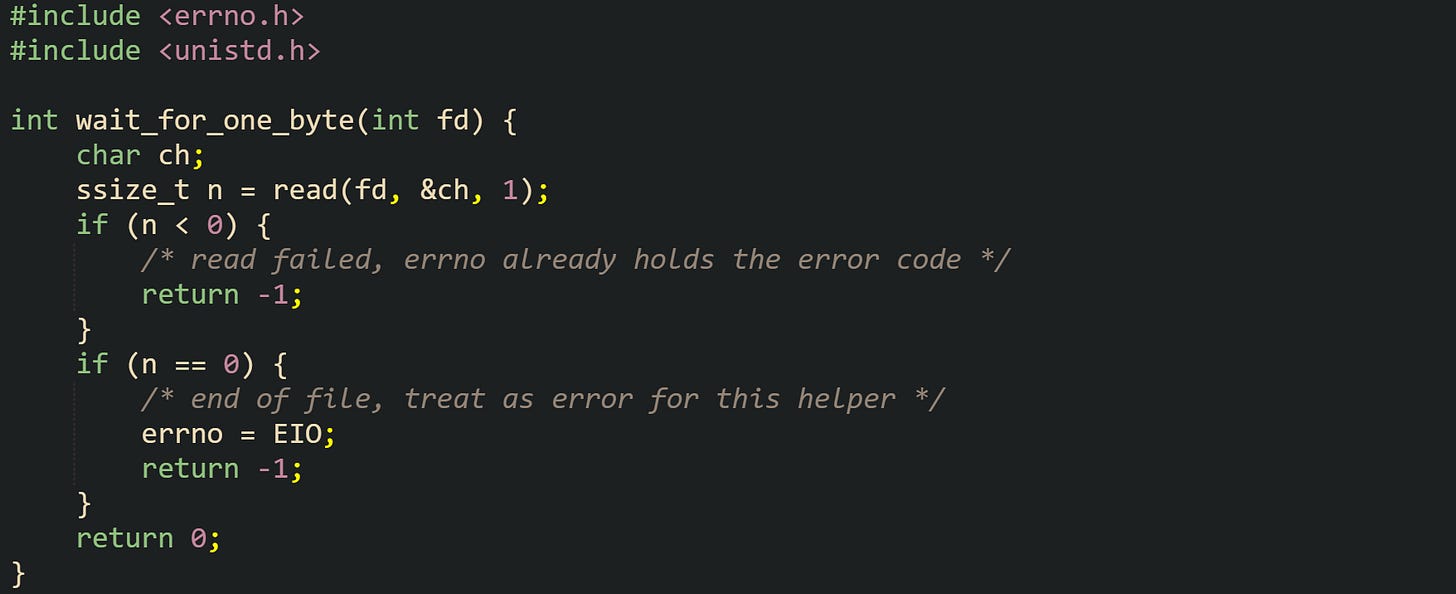

Let’s see a helper that wraps a system call and passes failure information up the chain:

This helper sets no new error code when read succeeds and returns zero. The original errno from the caller remains untouched in that case. When read fails with a negative result, errno already contains a code such as EINTR, EIO, or EBADF. When end of file appears where this helper expects more data, the helper assigns EIO so callers can see a consistent signal that the stream closed too early.

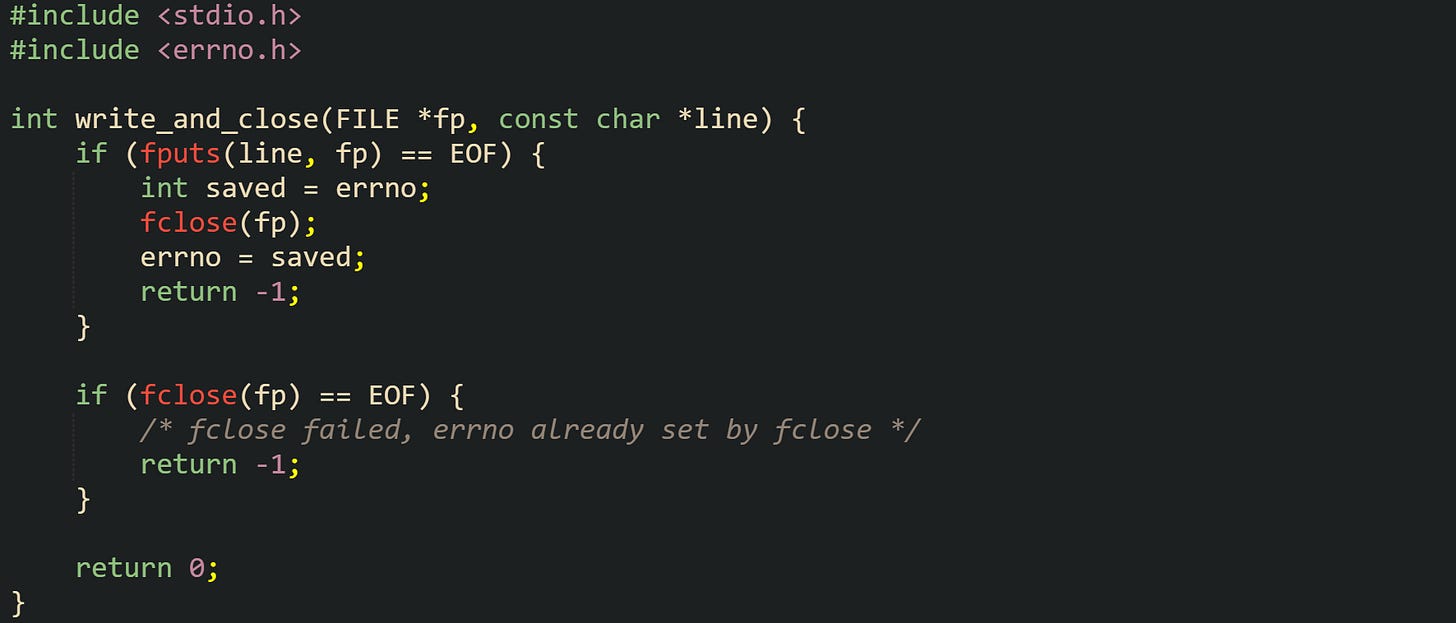

Code that needs to perform several operations before returning may need to preserve errno across internal clean up work. Many library calls can set errno, even when they are only freeing resources, closing file descriptors, or formatting text. To keep the original error visible, helpers often copy errno into a local variable, run clean up, then restore the saved value before returning.

Here, the helper preserves the error from fputs while still closing the stream. The caller that checks the return value and then reads errno after a failure will see the error code that caused the write to stop, not a later one that came from fclose. That small pattern of saving and restoring errno helps keep error messages accurate when several functions run as part of one higher level operation.

Static analysis tools can examine this style of code and flag suspicious uses of errno, such as reading it without any failing call on that path, or overwriting it before the caller has a chance to react. That automated pass complements testing and code review, especially in large C code bases.

Presenting Errors To Users

User facing messages usually need prose, not just a number. The C library offers helper functions that translate errno values into human readable strings, which can then be written to logs or to standard error. Those helpers make it easier to keep messages consistent for the same error codes across a project.

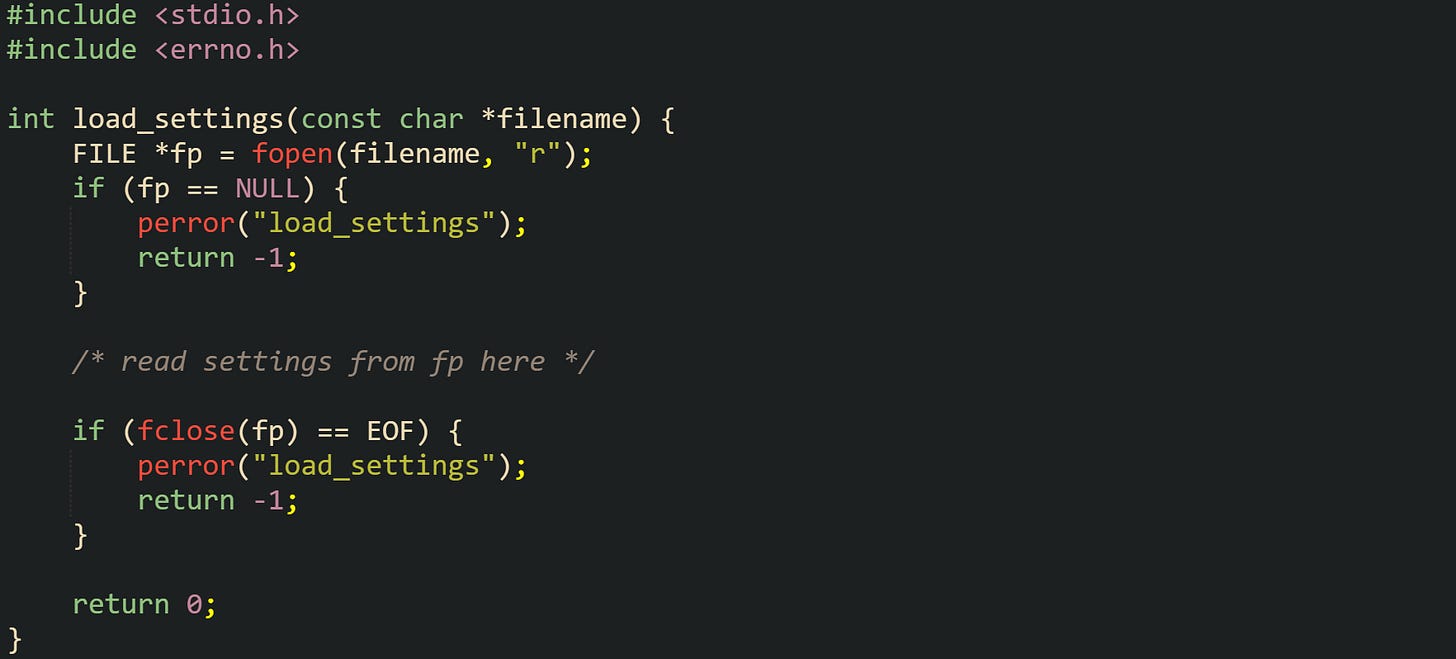

The function perror in <stdio.h> reads the current value of errno, prints a prefix that you supply, then appends ": ", an error string, and a trailing newline to the standard error stream. That behavior gives short, regular messages for common problems such as missing files or permission failures.

In that example, the helper uses perror at two different points but passes the same prefix string. An error during fopen or fclose produces messages that begin with load_settings and end with standard library text such as No such file or directory or Bad file descriptor, depending on the problem. That pattern is common for small tools that want consistent diagnostic lines without writing custom formatting code for each error.

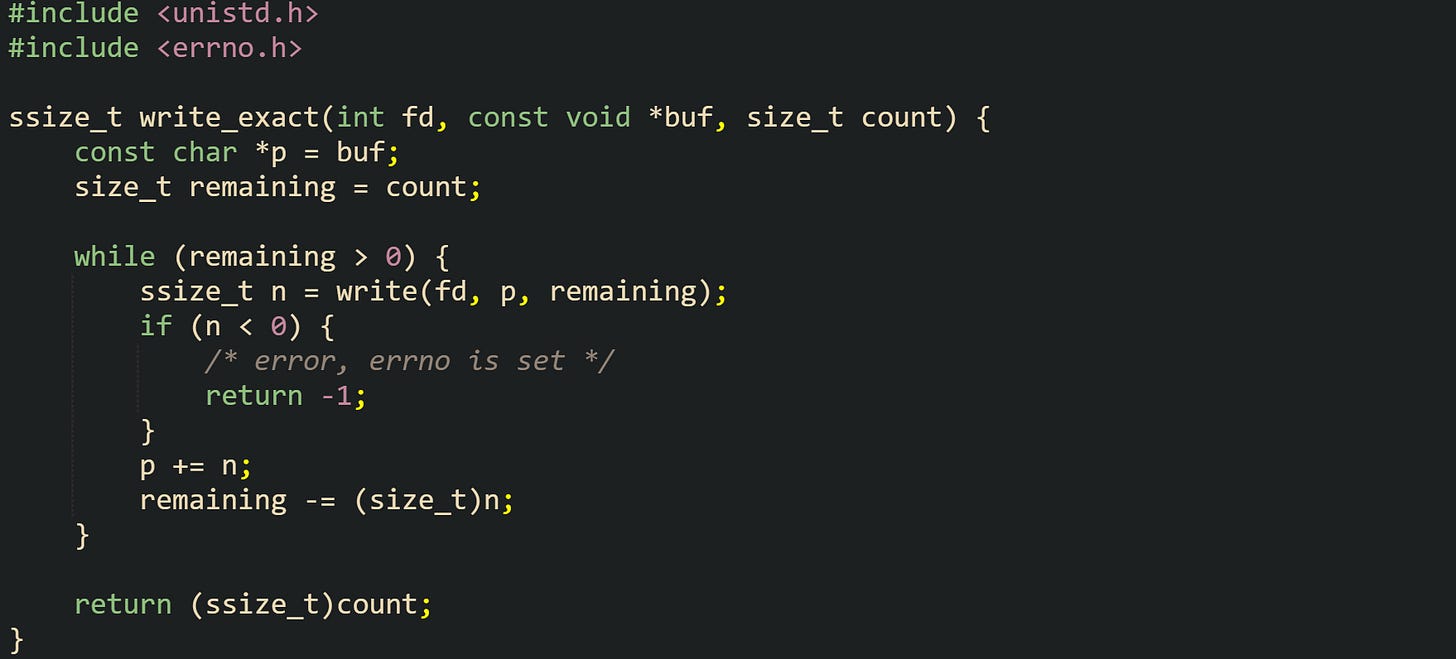

For more control, strerror in <string.h> maps an integer error code to a pointer to a static string. Code can then feed that pointer into fprintf, logger functions, or other formatting layers. Because strerror can change errno internally on some platforms, a frequent pattern is to copy errno first, then call strerror with the saved value.

This helper turns any errno value into a compact log message that names the operation, shows the numeric code, and prints the string returned by strerror. A caller that just saw fread, fwrite, or fsync fail can call log_file_error("fsync") while errno still holds the relevant value and get a consistent entry in a log file.

Threaded C applications that need fully thread safe error strings can use variants such as strerror_r or strerror_l where available. These functions avoid returning pointers to shared static buffers and instead write into caller supplied buffers or depend on locale objects. Details for those variants live in POSIX and platform manuals, but the high level idea is the same: turn an errno code into a readable string that can be reported without losing information in concurrent code. Static analysis tools help by warning when caller code passes buffer sizes that are too small or ignores return codes from those variants.

Conclusion

C error handling rests on two main tools, return values from functions and the shared errno indicator that explains why a call failed. When code checks status results right away, preserves errno where needed, and turns error codes into readable messages with helpers like perror and strerror, problems are easier to trace from the original library or system call up through higher level helpers. Static analysis tools fit into that idea by pointing out missed checks and risky errno use, so even low level C code can report failures in a precise and consistent way.

![#include <unistd.h> #include <errno.h> ssize_t read_line(int fd, char *buf, size_t maxlen) { size_t i = 0; while (i + 1 < maxlen) { char ch; ssize_t n = read(fd, &ch, 1); if (n < 0) { /* error, errno is set */ return -1; } if (n == 0) { /* end of file */ break; } if (ch == '\n') { break; } buf[i++] = ch; } buf[i] = '\0'; return (ssize_t)i; } #include <unistd.h> #include <errno.h> ssize_t read_line(int fd, char *buf, size_t maxlen) { size_t i = 0; while (i + 1 < maxlen) { char ch; ssize_t n = read(fd, &ch, 1); if (n < 0) { /* error, errno is set */ return -1; } if (n == 0) { /* end of file */ break; } if (ch == '\n') { break; } buf[i++] = ch; } buf[i] = '\0'; return (ssize_t)i; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!-Bfe!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7e12ae1f-5e03-44f9-88e7-86d13573c505_1758x910.png)

![#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> #include <errno.h> void log_file_error(const char *operation) { int saved = errno; const char *msg = strerror(saved); fprintf(stderr, "[file] %s failed with %d (%s)\n", operation, saved, msg); } #include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> #include <errno.h> void log_file_error(const char *operation) { int saved = errno; const char *msg = strerror(saved); fprintf(stderr, "[file] %s failed with %d (%s)\n", operation, saved, msg); }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!sGYH!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8289a714-0318-4f9a-8f63-f3f7f5a7712b_1775x424.png)