Execution Context and Call Stack in JavaScript

See how JavaScript organizes and runs your code

There’s more happening behind the scenes when you run JavaScript code than it may appear from the outside. Every time a function is called, a system is in place to determine what runs next, how data is passed around, and how the program keeps track of what’s going on. Two important concepts that manage all of this are execution context and the call stack. Today I’ll walk you through what they are, how they work together, and what actually takes place each time you run or return from a function.

How Execution Contexts Work in JavaScript

When JavaScript runs a script or when a function is invoked, it creates something called an execution context. The execution context serves as a container that holds everything JavaScript needs to run that specific block of code. This context is how JavaScript tracks variables, functions, and important references during execution.

What Happens Inside an Execution Context

Each execution context is like a snapshot of the environment in which the code runs. When the JavaScript engine creates an execution context, it prepares the environment for running the code. It checks the variables, the functions, and determines the value of this at that moment. It also sets up the scope chain, which allows the code to access variables from different levels of the call stack.

This process happens in two phases. During the creation phase, JavaScript scans the code, hoists declarations, and allocates memory for every variable and function it finds. During this stage the engine allocates memory for every declaration: var variables are set to undefined, function declarations are bound to their function objects, and let/const variables stay un-initialised in the temporal dead zone until control reaches them. In the execution phase, JavaScript starts running the code line by line.

The Global Execution Context

The global execution context is created when you run your script. Every JavaScript file or script you load starts with this global context. It’s where all global variables and functions are defined. The global context stays active throughout the entire script’s execution and is important for understanding how the system begins working. At the top level in non-strict code, this refers to the global object (window in a browser). In strict mode and inside ECMAScript modules, this is undefined. In Node’s REPL, the non-strict rule applies. Inside a CommonJS module, the top-level this is the empty object returned by module.exports. Any functions declared globally can be accessed from anywhere in the code. The global context stays for the lifetime of the page (in browsers) or the process (in Node). It disappears only when that environment itself ends.

Function Execution Contexts

Every time a function is called, a new execution context is created specifically for that function. This context is distinct from the global one. It handles the function’s own variables, parameters, and the value of this inside the function’s scope. It isolates the function’s environment, preventing it from interfering with the rest of the code outside the function.

When you call a function, JavaScript creates a new context and pushes it onto the call stack. This new context includes the function’s parameters, local variables, and the code within the function. These variables are stored in what’s called the variable environment. The function can directly use its own parameters and local variables, and through lexical scope any variables that exist in its outer contexts.

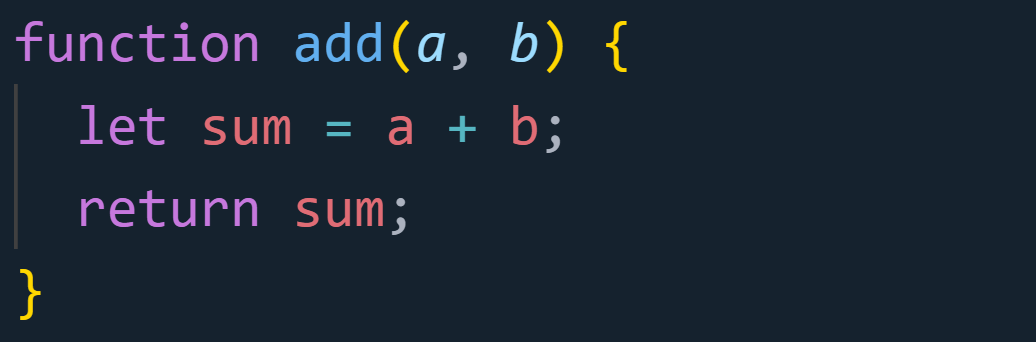

For example, let’s consider this function here:

When add(2, 3) is called, the JavaScript engine creates a new execution context for the add function. It sets up a, b, and sum as local variables inside that context. The function runs and returns the sum, and after that, the context is removed from the stack.

Variable Environment and Lexical Scope

Each execution context has its own variable environment, which keeps track of the variables and functions declared within it. For functions, this environment stores the parameters, treating them as local variables. Every function execution context operates within its own environment, so it doesn’t mix with others. A concept linked to the execution context is lexical scoping. This means that the position of functions and variables in the code determines how they are accessed. JavaScript first looks for variables within the current context. If they’re not found, it checks higher in the scope chain, looking through surrounding contexts all the way to the global context.

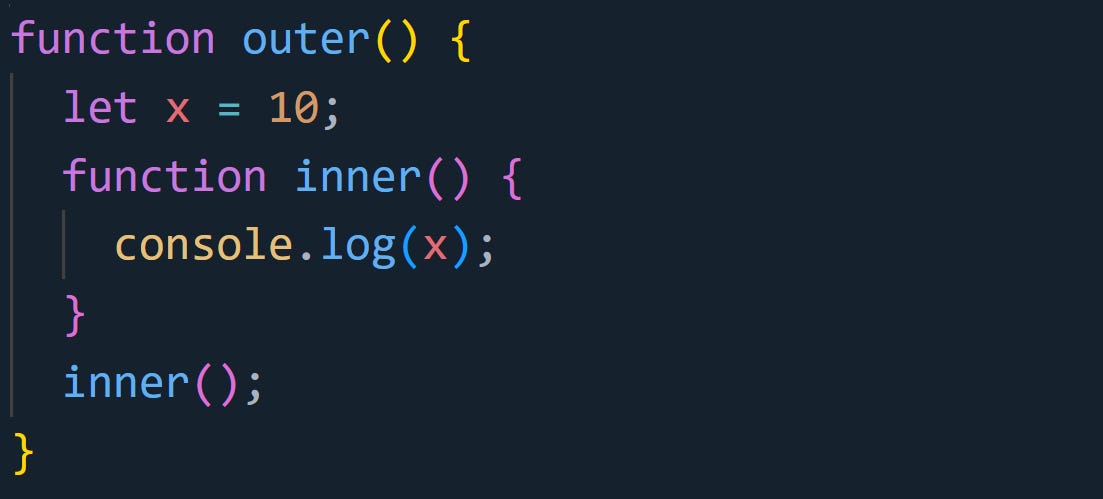

Here’s an example:

As inner() is called, JavaScript doesn’t find x within the local context of inner. It then moves up the scope chain to the outer function’s context, where it finds x. This is an example of lexical scoping in action. The inner function can access variables from the outer function because of how the execution context was created.

What Happens When a Function Returns?

After a function finishes its execution, its context is no longer needed. JavaScript pops the context off the stack; the memory tied to its local variables becomes eligible for garbage collection once nothing else references them. If the function returns a value, that value is passed back to the caller, and the context is fully discarded. The local environment is released unless something outside the function still holds a reference (for example, via a closure).

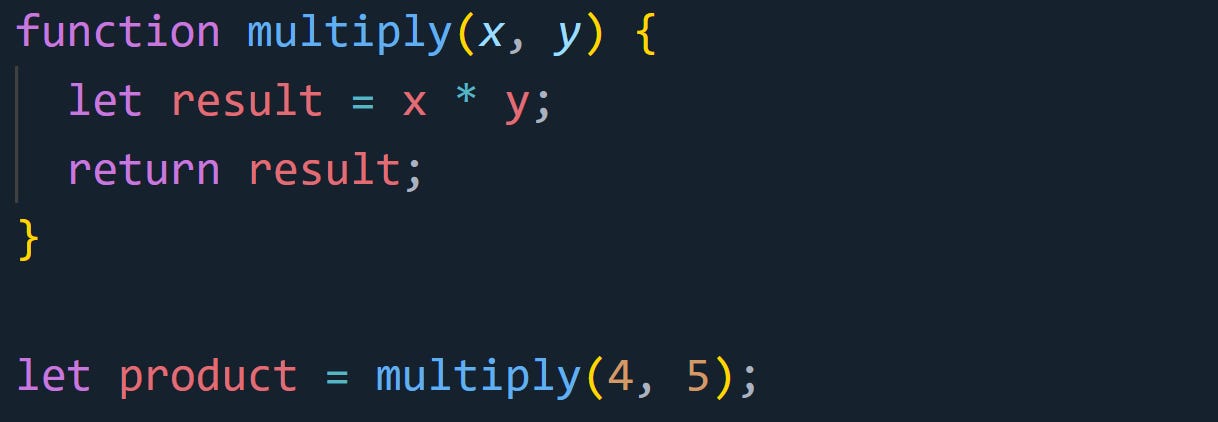

Let’s take a look at this:

When multiply(4, 5) is called, a new execution context for the function is created. The function runs, returns 20, and then the context is removed from the stack. The returned value is assigned to the product variable, and after the function finishes, its execution context is discarded.

The Lifecycle of Execution Contexts

To sum it up, the lifecycle of an execution context involves creating it, executing the code inside it, and removing it once the code finishes. This behind-the-scenes system is how JavaScript keeps function calls, scope, and this binding organised.

JavaScript creates a new execution context for every function call and even for the global environment. These contexts are temporary and created as needed, helping the program run efficiently. The call stack works with these contexts by pushing and popping them as functions are called and completed.

Call Stack Manages Execution

The call stack is one of the most important parts of JavaScript’s execution process. Without the call stack, JavaScript wouldn’t know which function is currently active or what to do next when a function finishes. The call stack organizes function calls and keeps the program running smoothly.

What the Call Stack Does

In simple terms, the call stack is a structure where each function call is placed in order. Each time a function is called, its execution context is added to the stack. When the function finishes, its context is removed, and the engine moves to the next function that’s still on the stack. The stack follows the last in, first out (LIFO) principle, meaning that the most recently called function will be the first one to finish.

When a function calls another function, a new context is pushed onto the stack. As each function finishes, its context is popped off the stack, and the engine moves on to the next function that was called earlier.

Simple Step-by-Step Example of the Call Stack

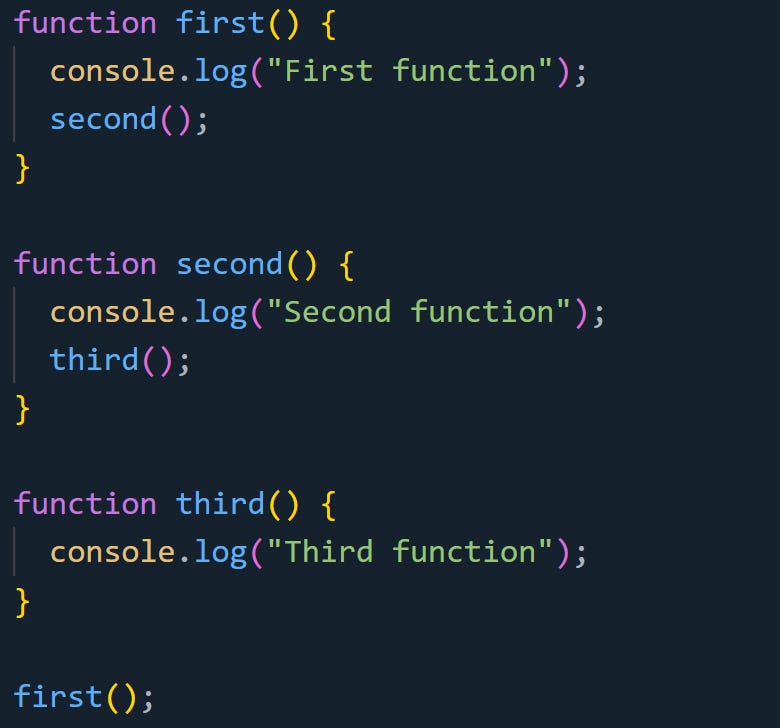

Let’s break it down to see what it looks like:

The code starts running and the JavaScript engine begins with the global execution context, which is always the starting point. This context represents the overall environment in which the program operates. From there, when first() is called, the engine creates a new execution context specifically for first() and adds it to the top of the call stack. At this moment, the stack now holds the global context at the bottom and first() on top.

As the first() function runs, it calls second(). To handle this, a new execution context for second() is created and pushed onto the stack above first(). The engine now shifts its focus to second(), where it runs and calls third(). Another context is created for third(), which sits on top of second() in the stack.

After third() finishes its execution and logs its message, its context is popped off the stack. The engine then goes back to second(), which completes its task and removes its own context from the stack. Once second() is done, the engine returns to first(), which finishes its final tasks and is removed from the stack as well.

With all functions completed and their respective contexts removed, the call stack is empty, signaling the end of the program’s execution.

How the Stack Controls Synchronous Execution

JavaScript executes the call stack synchronously, meaning it processes one line of code at a time, in the order it appears. The call stack is what keeps track of this process, so one function is fully executed before moving to the next.

This is why, in a synchronous program, each function waits for the one before it to finish. The function at the top of the stack is the one that is running. When it finishes, it’s removed, and the engine moves on to the next function in line.

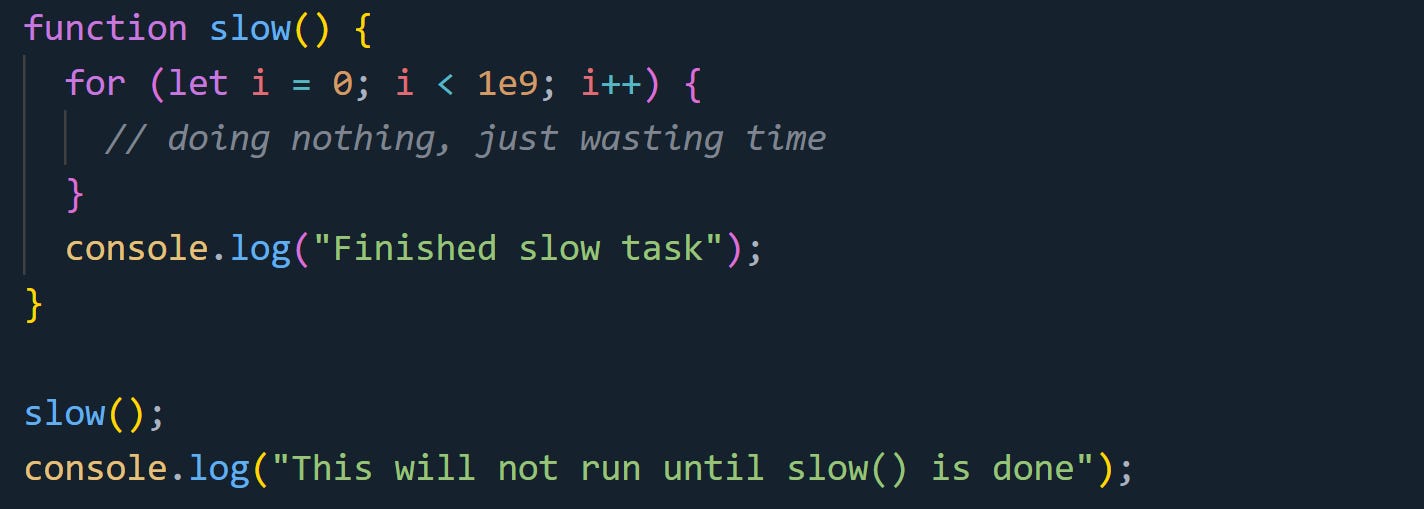

If you have a function that runs a long loop or does a heavy calculation, it will block the stack until it finishes. This means other code can’t be executed until that function has completed. This is why performance can suffer if there are long-running tasks. To solve this, JavaScript allows you to break tasks into smaller pieces or run them asynchronously.

Here’s a look at how this blocking behavior works:

JavaScript can’t execute console.log("This will not run until slow() is done") until the slow() function has finished. The JavaScript thread stays busy until slow() completes, so nothing else can run.

Call Stack and Errors

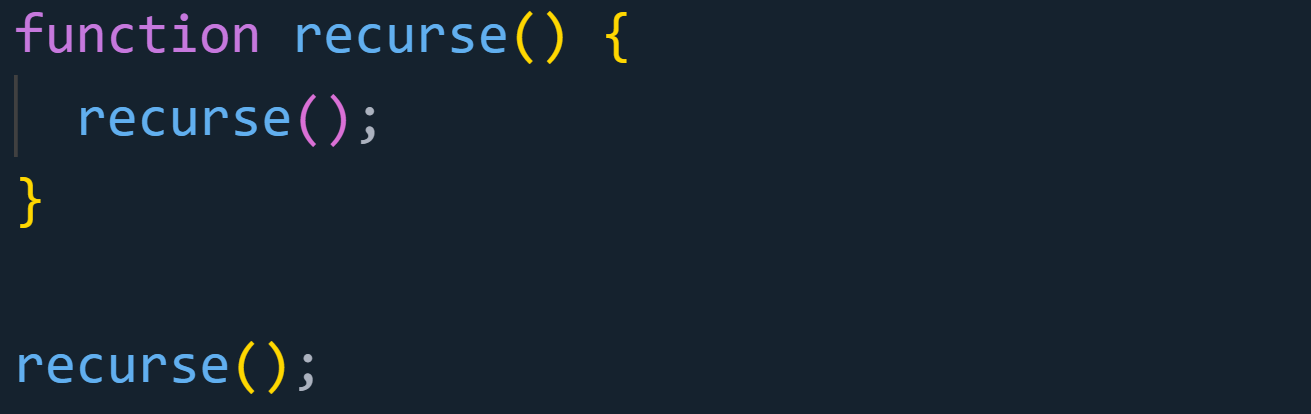

Sometimes, the call stack runs into trouble if too many function calls are made without returning. This can lead to a stack overflow error. This happens most commonly in recursive functions where there is no condition to stop the recursion.

Here’s what that can look like:

recurse() calls itself repeatedly, each time adding a new context to the stack. But because there’s no end condition, the stack keeps growing until it runs out of space, resulting in a stack overflow error. Give recursive functions a clear exit condition to prevent this.

Managing the Stack with Asynchronous Tasks

While the call stack handles synchronous code, JavaScript also has ways to manage tasks that take time to complete, like waiting for a response from a server or processing user input. Instead of blocking the call stack with these tasks, JavaScript offloads them using mechanisms like the event loop.

For example, when using setTimeout or making an HTTP request, JavaScript doesn’t add these tasks to the call stack right away. Instead, the engine registers the work with the host (browser/Node) and puts the callback in a task queue. When the call stack is empty, the event loop pulls the next task from the queue and pushes its callback onto the stack.

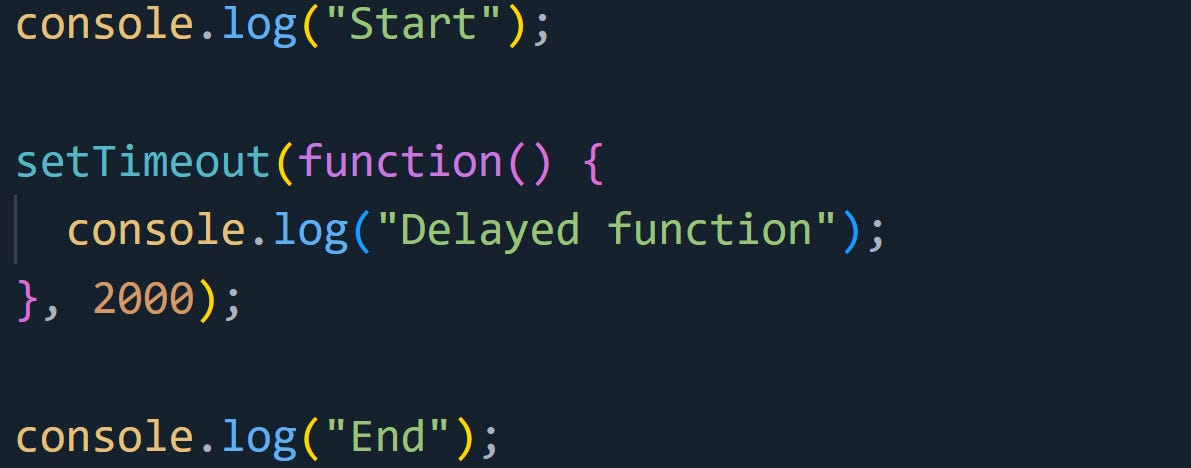

Consider this example with setTimeout:

In this one, “Start” and “End” are printed first. The setTimeout callback isn’t added to the call stack immediately. Instead, it goes to the event loop, which waits for the specified time (2 seconds in this case) before pushing the callback onto the stack for execution. This allows JavaScript to continue executing other code without delay.

Conclusion

The call stack and execution context work together to control the flow of JavaScript code. Every time a function is called, a new execution context is created and placed on the call stack, so the engine knows which function is currently active and how to handle it. As functions complete, their contexts are removed, keeping everything organized and in the right order. This system is behind everything JavaScript does, from variable tracking to determining which function runs next.