Fast exponentiation shows up whenever code needs to raise numbers to large powers without spending a lot of time on repeated multiplication. Java provides Math.pow and BigInteger.pow (with an int exponent), but many developers only run into the idea that makes these calls fast much later in their learning. At its core, fast exponentiation uses binary arithmetic to turn a long chain of multiplications into a compact run of squaring steps with a few well chosen extra multiplies.

Fast Exponentiation Basics

Generally speaking, fast exponentiation rests on a small set of ideas, but those ideas sit on top of more familiar ground. Most people first meet integer powers as repeated multiplication, where a value like 3^5 just means 3 * 3 * 3 * 3 * 3. That maps nicely to a loop in Java, so it feels natural to write code that walks through the exponent and multiplies the base again and again. Once exponents grow large, that basic plan turns into a long stretch of work, and it becomes easier to see why a different structure helps. Before getting to the faster method, it helps to anchor that comparison in a solid view of the slow one and in the algebra that makes the faster one valid.

Naive Exponentiation With Loops

Naive exponentiation describes any method that treats b^e purely as repeated multiplication. When someone writes 2^10 on paper, many readers think of ten copies of the number 2 being multiplied. Translating that idea directly into Java leads to a loop that starts with 1 and keeps multiplying by the base until the loop has run exp times. That translation is direct and maps well to the mental picture of “do this multiplication exp times”.

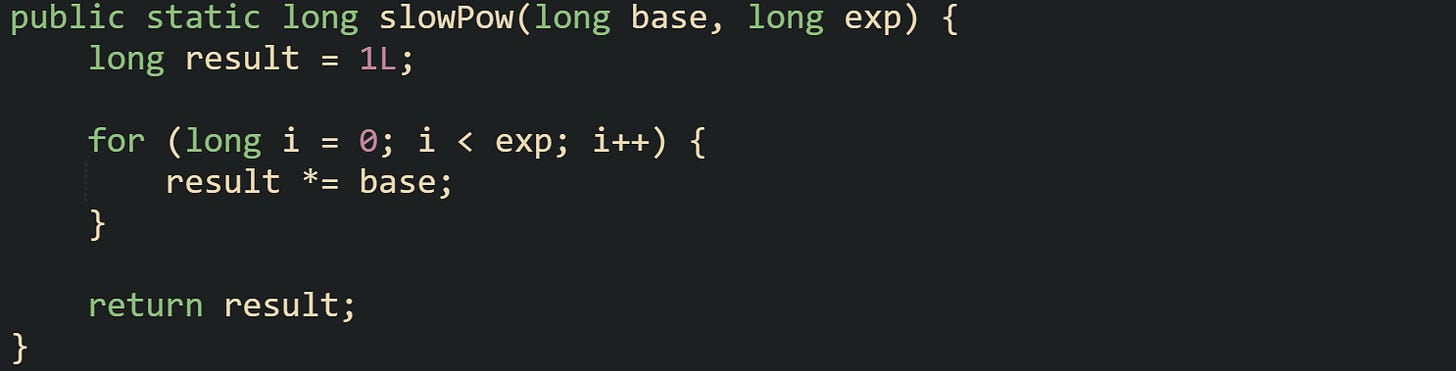

A first cut at that kind of method for non negative exponents can look like this:

This method uses result as an accumulator. The loop variable i walks from zero up to one less than the exponent, and every pass multiplies result by base. After the loop finishes, result holds base raised to exp, as long as the intermediate products stay inside the range of long.

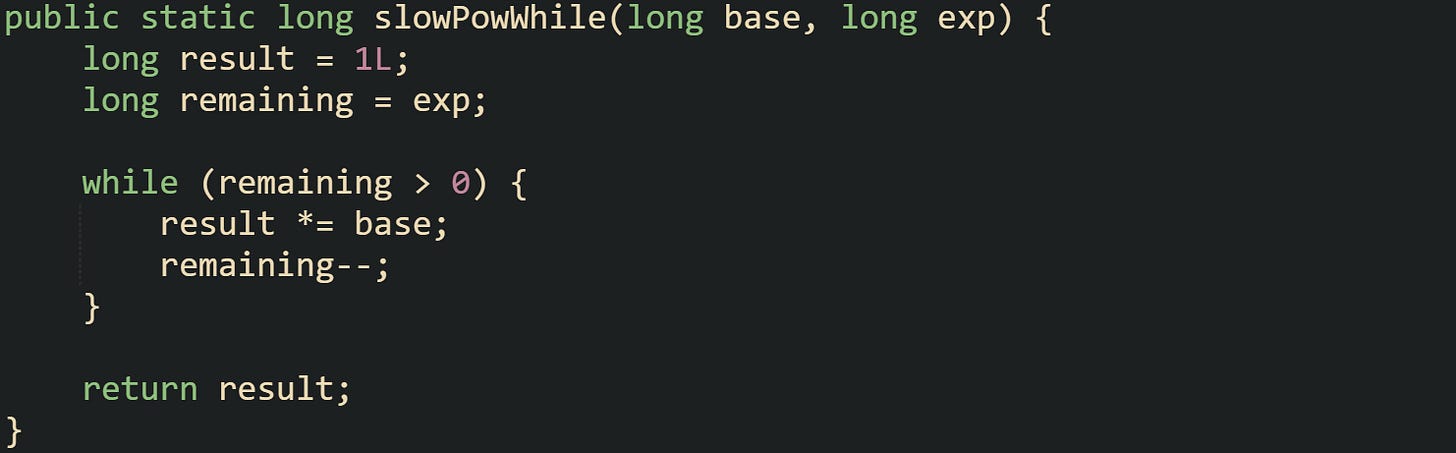

The while loop expresses the same idea in a slightly different style, which some developers find easier to adapt when they experiment with extra conditions or logging.

This version moves the loop counter into a variable named remaining, which counts down toward zero. That name reflects the fact that each pass burns one unit of exponent until none are left. The behavior is the same as the for loop version, and performance characteristics match as well.

Both of these methods have the same scaling behavior. For an exponent of 10, they perform ten multiplications. For an exponent of 1_000, they perform one thousand multiplications. In general, the number of multiplications grows in direct proportion to the exponent. Written another way, the work cost grows on the order of exp. That scaling becomes painful with large exponents. A call like slowPow(2, 1_000_000_000L) would ask the runtime to carry out one billion separate multiplications, not counting the loop overhead. Even with modern hardware and a highly optimized JVM, that kind of workload for a single exponentiation call lands far outside practical bounds.

The naive loop also has trouble when callers work with BigInteger values. Repeated multiplication on large integers is much heavier than multiplication on long, so a method that treats each unit of exponent as one more multiply becomes even less attractive. These concerns motivate a method that still respects the algebra of exponents but reuses work more effectively.

Idea Behind Repeated Squaring

Repeated squaring enters the picture from a basic algebra rule about exponents. When two powers share the same base, the exponents add, so b^a * b^c equals b^(a + c). That identity lets a large exponent be built out of smaller ones in a flexible way. Binary representation of the exponent provides a very structured way to split it into a sum of powers of two, and that structure guides the repeated squaring method.

Take the exponent 13 as a running example. Written in binary, 13 turns into 1101. Reading those bits from right to left, the least significant bit represents 1, the next one 2, then 4, then 8. Only the positions with a 1 contribute to the sum, so 13 becomes 8 + 4 + 1. Translating back to exponents, that gives: b^13 = b^(8 + 4 + 1) = b^8 * b^4 * b^1.

Those component powers can be built by squaring. Starting with b^1 gives a base point. Squaring that value once yields b^2. Squaring b^2 yields b^4. Squaring b^4 yields b^8. With those three squaring steps, the code has reached the largest power of two less than or equal to 13. Multiplying the selected powers that correspond to the 1 bits in the exponent reconstructs b^13.

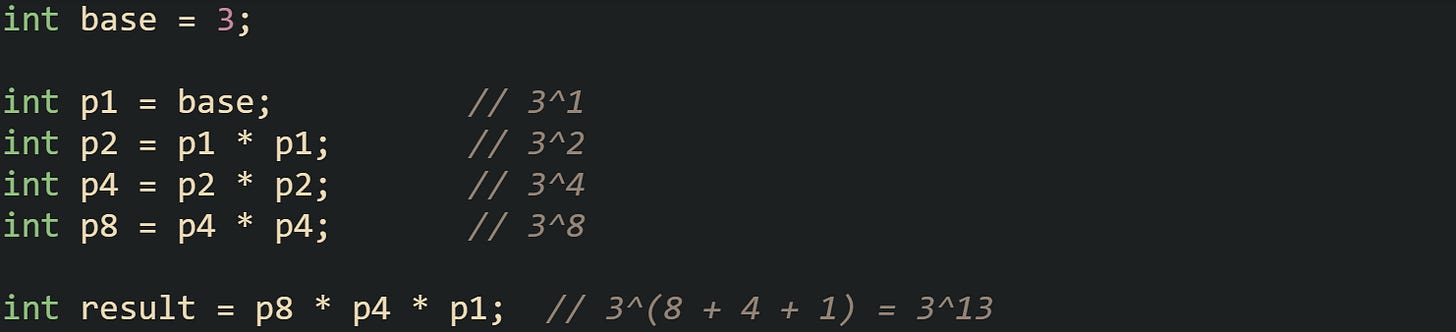

The sequence looks like this:

This small code fragment hard codes the powers, but it mirrors the general idea. Each squaring step doubles the exponent, and only the powers that correspond to 1 bits in the binary form of the exponent have to be multiplied into the final result. For 13, those are 1, 4, and 8. If the exponent had been 12, with binary form 1100, the final product would involve b^8 and b^4, but not b^1.

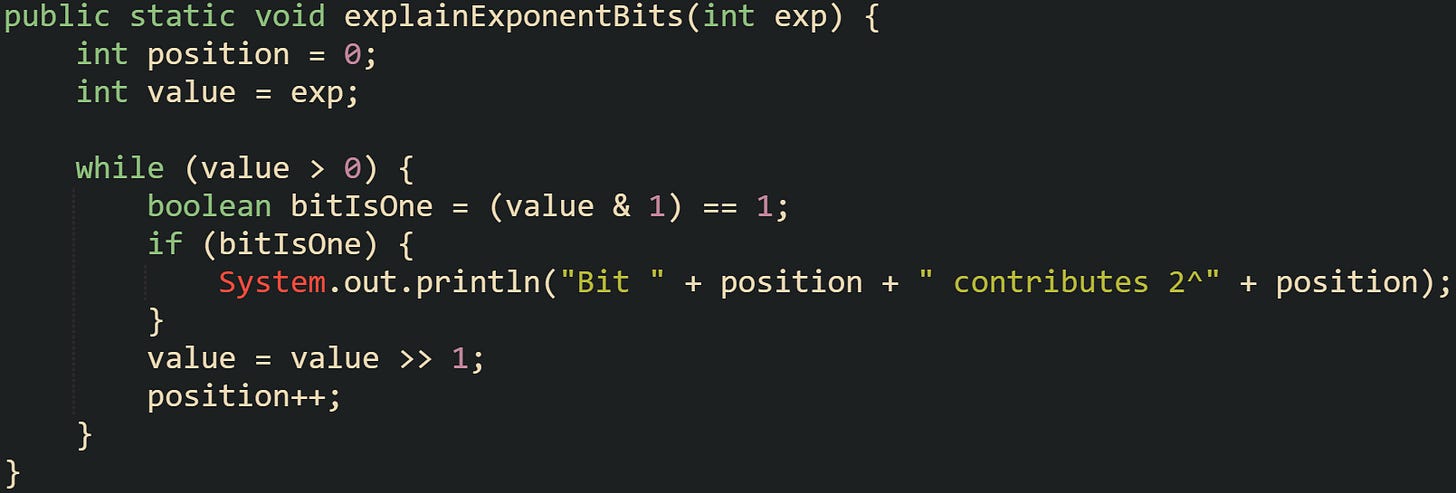

A more general view uses bit operations to walk through the exponent without writing out every case by hand. The core observation is that the least significant bit of an integer can be checked with a bitwise and operation against 1, and shifting the exponent right by one bit moves focus to the next position.

Calling explainExponentBits(13) walks across the bits of 13, starting at the least significant bit. The method prints a line only for positions where the bit is 1, and that series of lines matches the powers of two that add up to the original exponent.

Repeated squaring relies on this same information to decide when to multiply. While the algorithm runs, it maintains a current power of the base that doubles with each squaring step, along with a running result that starts at 1. Whenever the bit check reports 1, the running result picks up an extra factor equal to the current power. The current power then squares, and the exponent shifts so the next bit moves into place.

The big change is that the number of squaring steps and bit checks grows with the number of bits in the exponent, not with the exponent’s numeric value. A value near one billion has around thirty bits in binary form, so repeated squaring needs roughly thirty multiplications for the squaring steps and at most thirty more for the selected powers. That count stays tiny compared with the billion multiplications required by a naive loop, which is why repeated squaring sits at the heart of fast exponentiation.

Fast Exponentiation in Java Step by Step

Fast exponentiation logic turns into concrete Java code with only a few moving parts. The core idea is still the same binary view of the exponent, but now that idea gets expressed as a loop, some bit checks, and a pair of variables that evolve together. One variable keeps a running result, and the other keeps a current power of the base that keeps squaring. As the loop walks through the bits of the exponent, the code decides when to multiply the result by that current power and when to skip. From there it is natural to branch out into negative exponents and modular arithmetic, while still keeping the same structure.

Iterative Square Multiply Method

Many fast exponentiation routines in Java follow a style called square and multiply, written with a compact loop that works through the exponent one bit at a time. Instead of looping as many times as the exponent value, the code loops as many times as there are bits in that exponent. For a long exponent that can mean at most sixty three passes, even when the numerical value is very large.

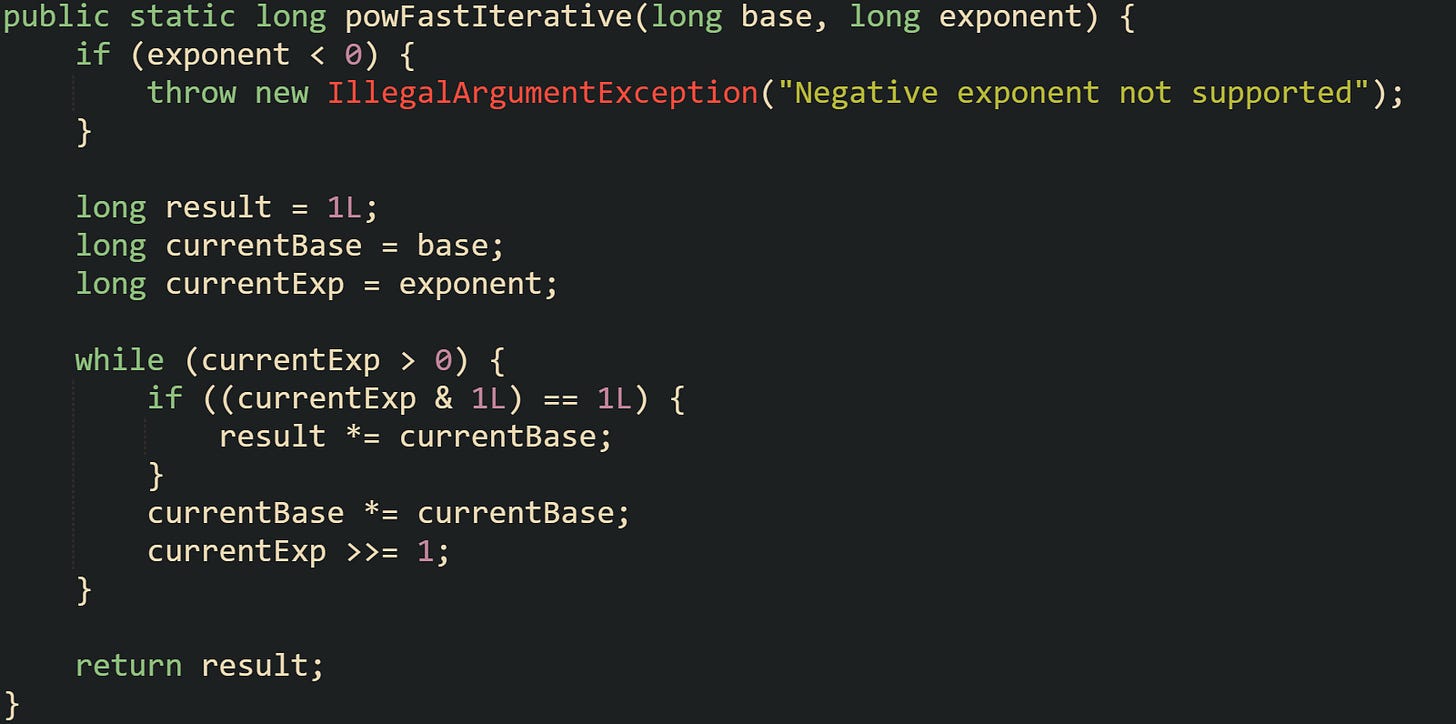

A basic version for non negative exponents with long arithmetic can look like this:

This loop reads the exponent from right to left in binary form. The expression currentExp & 1L checks the least significant bit. When that bit equals 1, the method multiplies result by currentBase, which at that moment holds some power of the original base. After that check, the code squares currentBase, moving to the next power of two, and shifts currentExp right by one bit so the next iteration focuses on the next bit.

For a call such as powFastIterative(3, 13), the loop passes through exponent bits that match the 1101 binary form of 13. The first iteration sees a 1 in the lowest bit, multiplies result by 3, then squares the base to 9 and shifts the exponent. Later iterations pick up the contributions from 3^4 and 3^8 where the bits are set, and skip 3^2 where the bit is zero. By the time currentExp reaches zero, the combined effect matches 3^13.

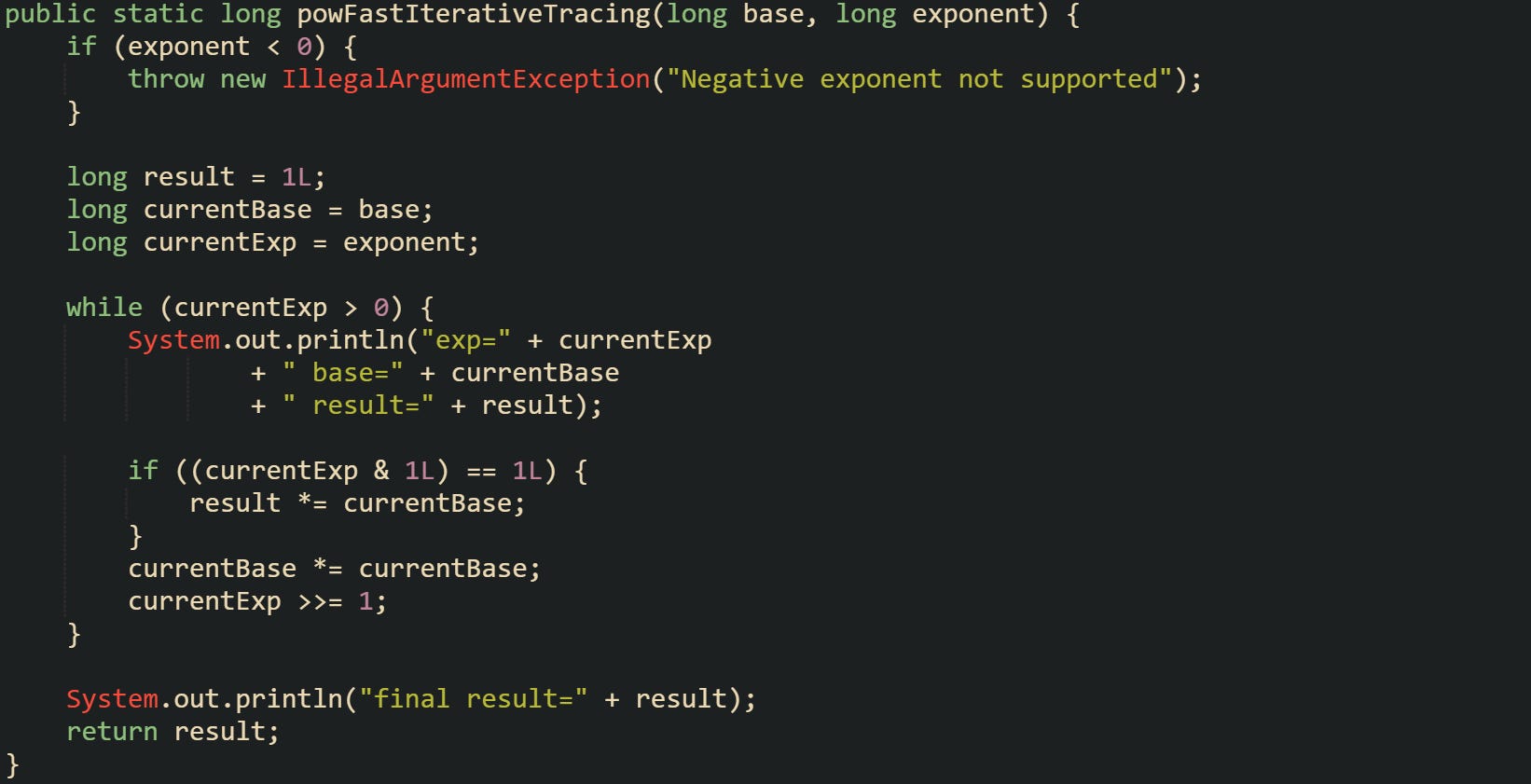

Sometimes it helps to see how the internal variables evolve. A small variant that logs state can give that view during learning or debugging.

Printed output from this method makes the algorithm less abstract, as it echoes the exponent bits and how they influence the running result. For large exponents, the output grows in proportion to the number of bits, not the exponent value itself, which reflects the same time saving that the algorithm brings.

Lots of projects work with non negative exponents, so an early guard against negative values keeps the method focused. When later sections extend the idea to other exponent ranges or numeric types, the same core pattern of bit checks, squaring, and shifting still sits at the center of the logic.

Handling Negative Exponents

Negative exponents change the story, because b^(-e) equals 1 / b^e when b is nonzero. That identity turns a negative exponent into a reciprocal of a positive exponent, and the same fast method for positive exponents still applies. The only difference lies at the edges, where the code must decide when to flip the result into 1 / value.

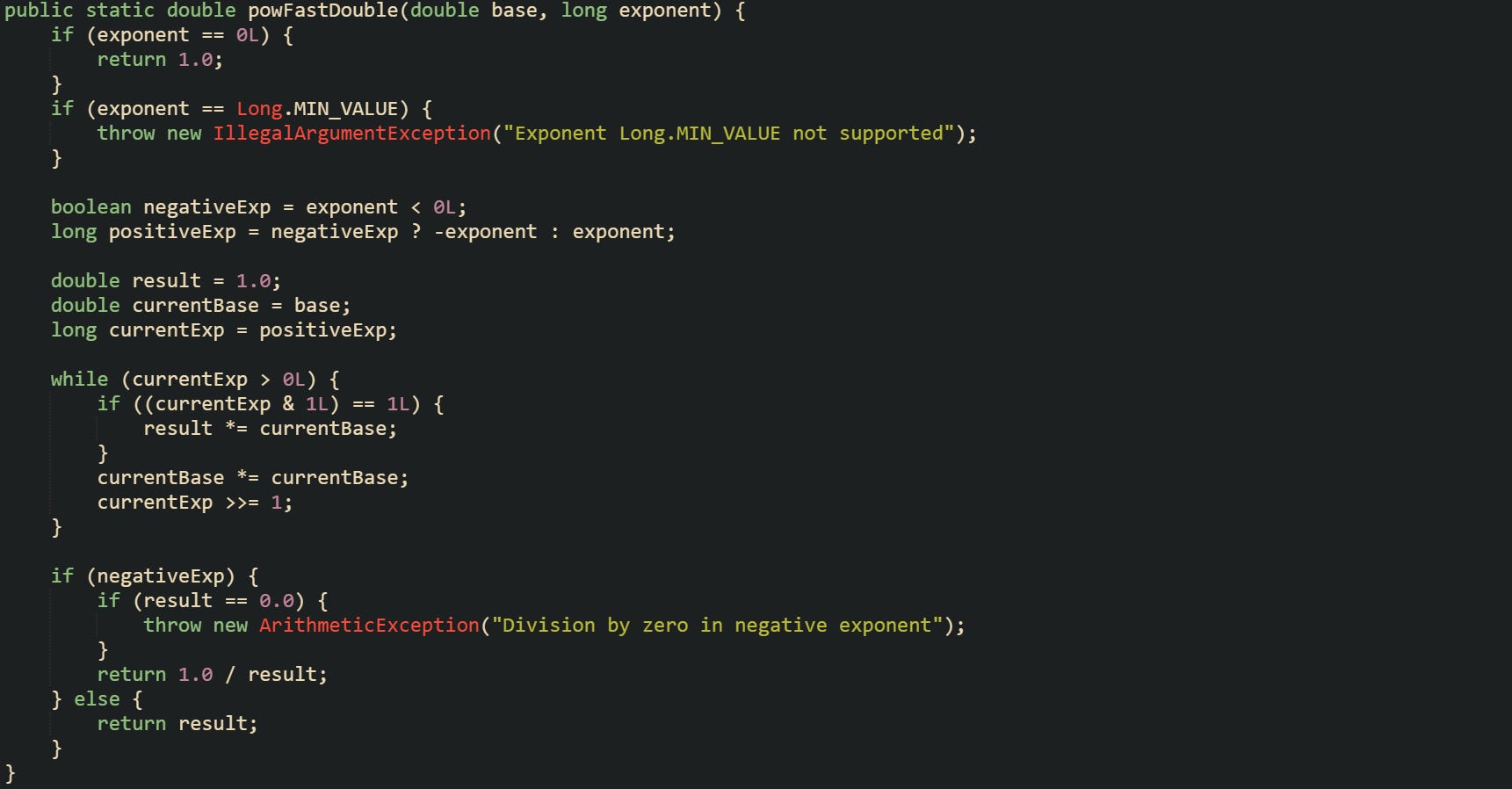

For integer types such as long, negative exponents naturally lead outside the integer world, because division brings fractions into play. Many Java developers move to double for that case, which trades exact integer values for floating point approximations. A fast exponentiation routine that handles negative exponents with double arithmetic can look like:

Logic inside the loop follows the same pattern as the integer method. The main difference sits in the preparation and the final step. The method records whether the original exponent was negative, rejects the Long.MIN_VALUE case where a negation would overflow, flips other negative exponents to positive values for the bit walk, and then either returns result directly or returns its reciprocal. A small guard against division by zero protects the case where a negative exponent meets a base that leads to a zero result after rounding.

Most general purpose code that needs real number exponentiation leans on Math.pow, which already handles many corner cases and numeric subtleties. Fast exponentiation by hand tends to appear in places where the exponent is integral, the base might be integral, and the developer wants tight control over overflow, rounding, or performance.

Fast Exponentiation for Modular Arithmetic

Many practical uses of fast exponentiation sit inside modular arithmetic. Expressions like base^exponent mod m show up in cryptography, random number generators, and number theory utilities. The goal there is not the raw value of base^exponent, which can grow enormous, but that value reduced modulo some integer m. Fast exponentiation blends very naturally with this world, because the loop already centers on multiplying and squaring, and each of those steps can fold through a modulus before the values grow too large.

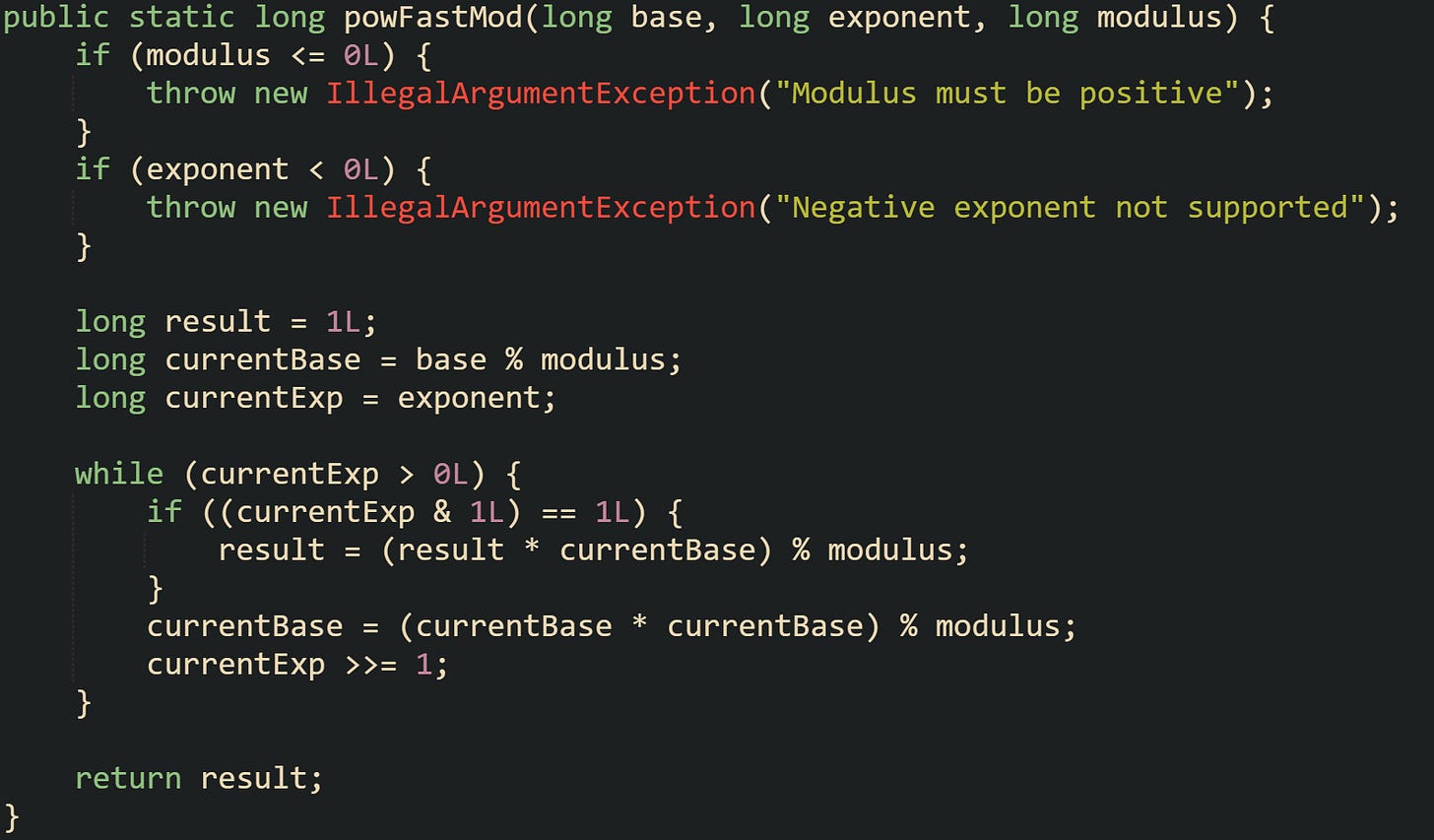

Modular exponentiation with long values typically keeps the same square and multiply structure while wrapping each multiplication with a modulus operation.

Two details stand out in this method. The base moves through base % modulus at the start, so values feed the loop already reduced into the modular range. Then every time the code multiplies result by currentBase, or squares currentBase, it applies the modulus again. That repeated reduction keeps values bounded by the modulus, although long overflow can still arise if the intermediate multiplication exceeds the range of long before the modulus step reduces it.

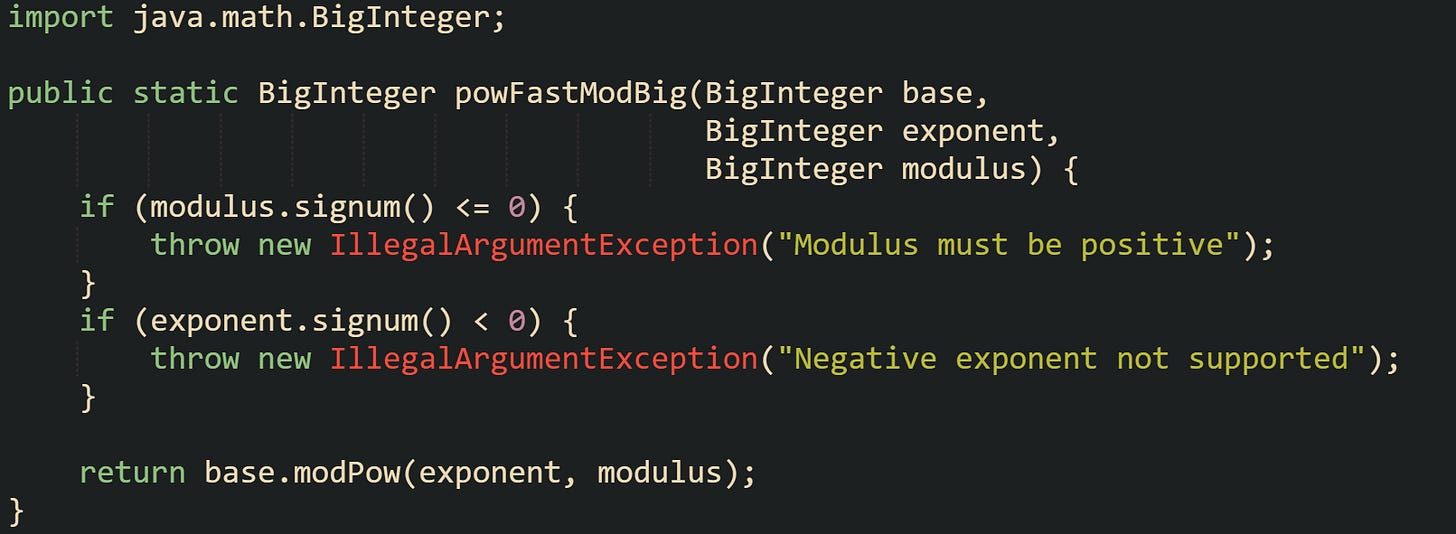

For larger integers, such as those used in modern public key cryptography, most projects switch to BigInteger. That type supports arbitrary precision integers and carries its own modular exponentiation helper. Code that needs base^exponent mod m with very large values can rely on that helper directly.

Here, the method delegates the heavy lifting to BigInteger.modPow. Internally, modPow follows a strategy based on exponent bits and square and multiply logic, extended with algorithms that handle very large integers and choose efficient multiplication routines. From the caller’s point of view, the method still matches the mental model built earlier, where the exponent breaks into powers of two and only the powers with 1 bits contribute to the final product inside the modular world.

Conclusion

Fast exponentiation in Java ties binary exponents directly to a short, repeatable set of steps, where bit checks decide when to multiply and squaring drives the base through powers of two. Naive loops grow work in proportion to the exponent value, while square and multiply grows with the number of bits, which keeps the cost low even for very large exponents. The same mechanics carry over when the code moves from long to double, or from plain arithmetic to modular arithmetic with long and BigInteger, so the picture stays consistent whether the goal is Math.pow style behavior, exact integer powers, or BigInteger.modPow for large modular exponents.