Data doesn’t always stay in neat rows and columns. Sometimes one row holds a whole list, like an array of tags or a set of IDs. That can work well in formats that don’t follow a fixed structure, but it doesn’t line up with how SQL expects each column to hold a single value. If you need to search, join, or filter based on the items inside that list, you’ll need to break it apart. This process is called flattening. It turns a single row with a list into multiple rows, each with one item from the list. PostgreSQL (and other array‑aware dialects such as BigQuery) handles this with two features working together. UNNEST pulls apart the list, and CROSS JOIN attaches each value to the rest of the original row. The way this works comes down to how SQL handles functions that return multiple rows and how it repeats data across joins.

Breaking up arrays with CROSS JOIN and UNNEST

Some columns end up holding full arrays instead of single values. That happens when data comes from APIs, logs, or JSON imports. SQL will store them, but to group, filter, or join the items inside, you’ve got to unpack them first. That’s where UNNEST and CROSS JOIN come in. UNNEST pulls an array apart into rows. CROSS JOIN repeats the rest of the row to match the number of unwrapped values. Together, they let you take nested or packed-in values and treat them like they were stored flat all along.

What UNNEST Does by Itself

UNNEST is a special kind of function. It doesn’t return a single value like most functions. Instead, it returns multiple rows, which the engine treats like a temporary table. That makes it a “table function,” and it behaves more like a data source than a single-cell value.

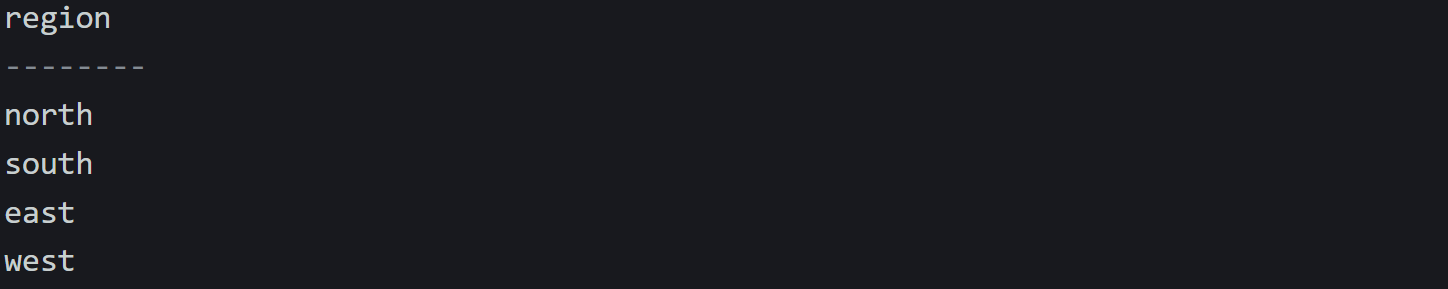

Start with something small to see it in action.

This gives:

That one expression just created four rows, all from a single array. SQL treated each item in the array as a separate output row. This is different from something like string_to_array, which creates a single array result, or array_length, which gives one number. With UNNEST, each part of the array becomes a record you can interact with like any other row in a query.

The function can also work with arrays of numbers or dates:

Or:

Those return one row per value. Nothing else is attached to the result because you’re not pulling from a base table. You’re just calling a function. This makes it useful for quick checks or to generate rows on the fly for use in a larger query.

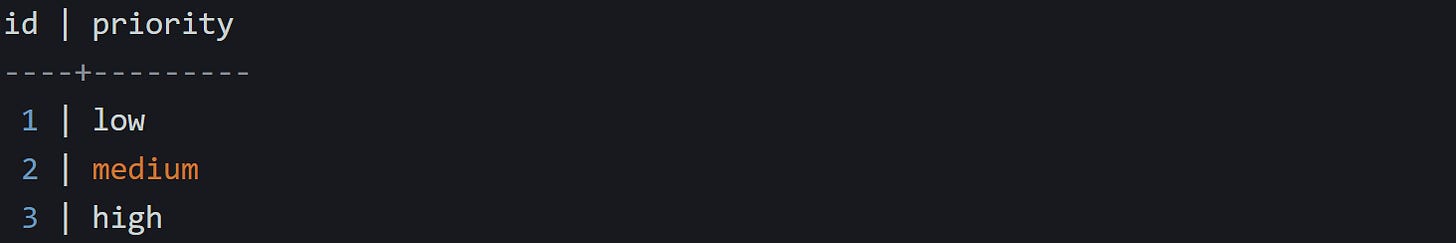

If you want to work with multiple arrays in sync, you can pass several of them to UNNEST at once. It will return rows by position, matching the first item in each array together in row one, then the second in row two, and so on.

Result:

This is a great way to treat parallel arrays as a single stream of rows. If the arrays aren’t the same length, PostgreSQL fills the gaps with NULL, so you will want to account for that in whatever comes next.

How CROSS JOIN interacts with UNNEST

UNNEST gives you rows, but only from the array you pass to it. If you want to pull arrays from a column in a real table and expand each one next to its row, you need to bring in a join. CROSS JOIN is the cleanest way to do that. It attaches every row from one side to every row from the other. But when you pair it with UNNEST, the number of rows is limited to just the length of the array being unwrapped for that specific row.

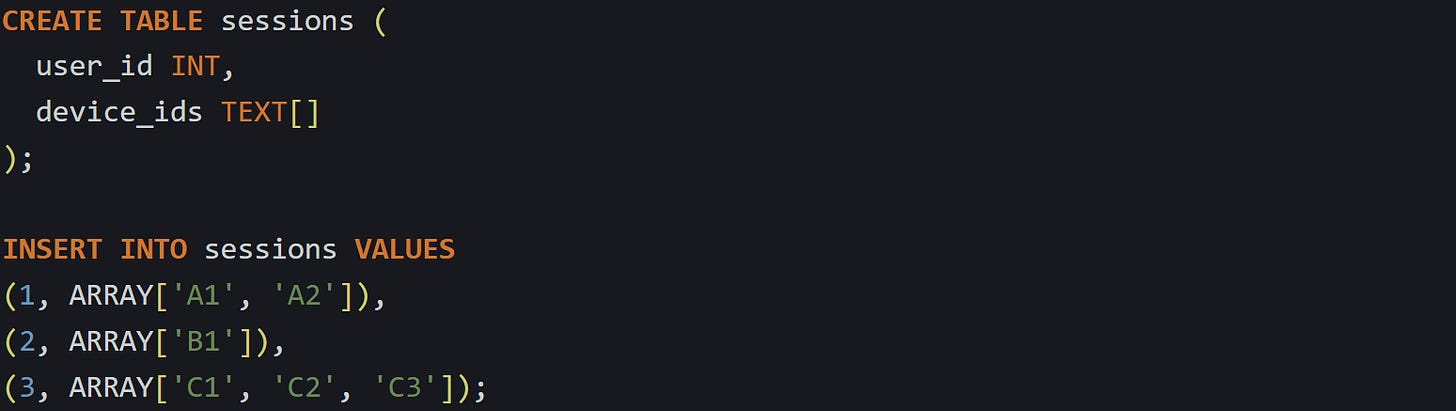

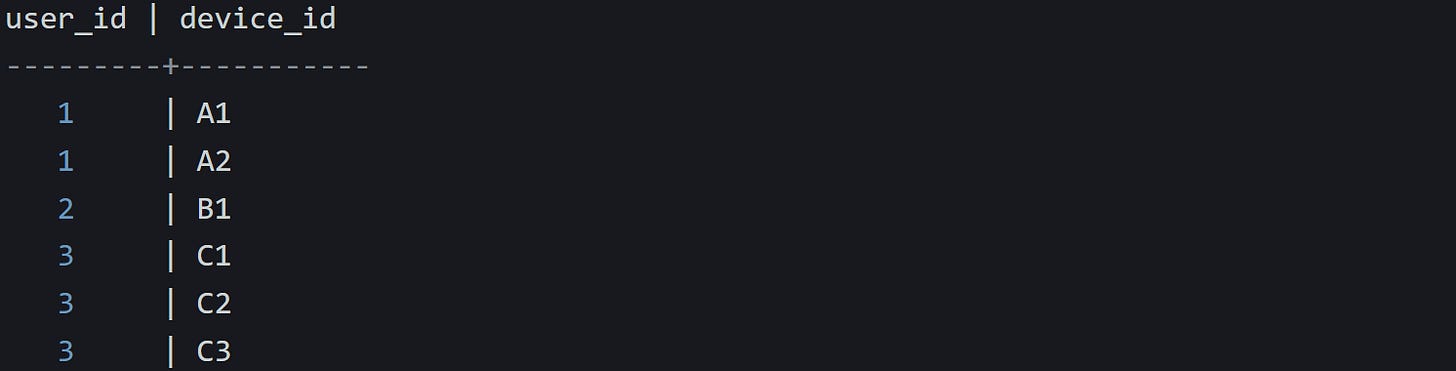

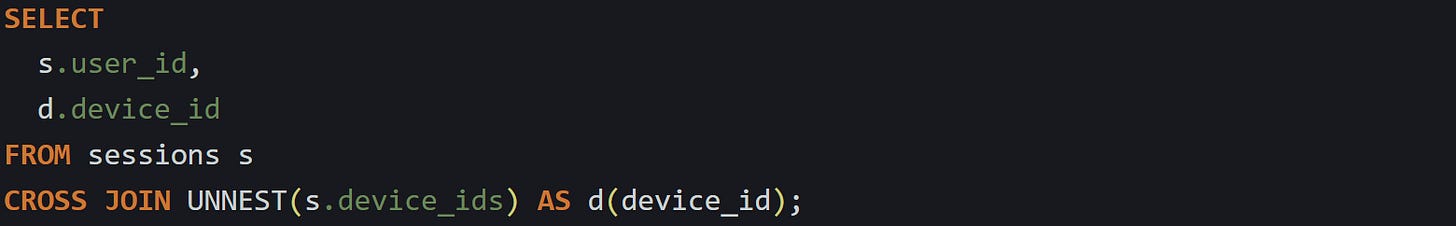

Say you’ve got this table:

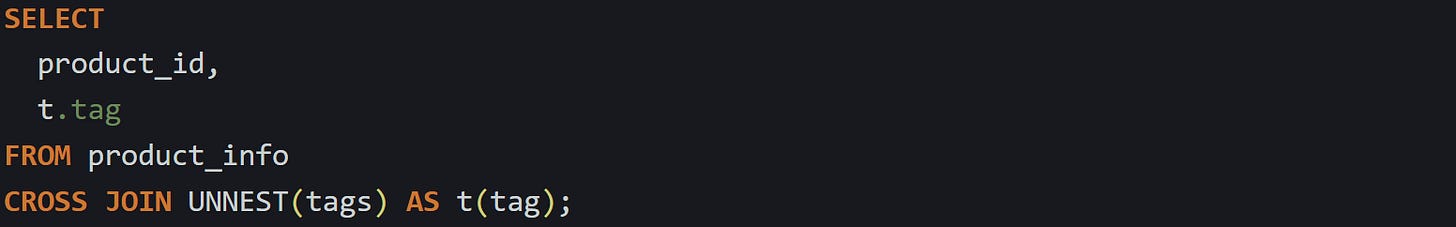

Now you want one row per device, keeping the user_id with each:

You’ll get:

Behind the scenes, SQL reads each row, unwraps its device_ids array, then creates one row for each item inside that array. The original row is duplicated as needed. Each unwrapped value gets its own copy of the data on the left. This is different from a normal CROSS JOIN, where every row on the left is joined with every row on the right. Here, UNNEST is treated as a dependent expression. It’s evaluated once per input row. This behavior is technically “lateral,” but with CROSS JOIN UNNEST(...) you don’t need to say that explicitly.

The nice part is you don’t have to worry about keeping things in sync. SQL takes care of lining up each value with its source row.

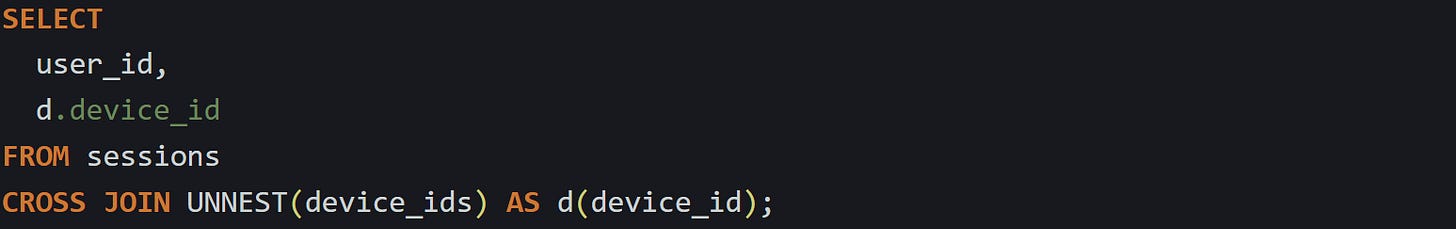

The names can get a little clunky, so you can alias both the UNNEST result and its columns like this:

That makes the query a bit easier to read, especially when you’re unpacking more than one field.

This pattern is common in reporting, analytics, and anywhere JSON-like data ends up in your relational model. Instead of splitting arrays in your app, or storing them in separate tables, you let the database unwrap them directly and treat them like a stream of values. CROSS JOIN UNNEST(...) works best when each item in the array should be treated like its own row. It’s fast, readable, and works well with filtering, grouping, and joins that follow. If you’ve got a table where one column holds a list, and you want to make each item first-class in your query, this is the tool to reach for.

What happens when the array is empty or NULL

Flattening array values works well when there’s actually something to unpack. But that doesn’t happen every time. Some rows have no values in the array, and others don’t have an array at all. These cases affect what comes out of UNNEST, and SQL treats them differently. That’s important when you expect one output row for every input but end up with some missing.

An empty array still counts as an array. A NULL does not. That difference drives how SQL decides what to do next.

Empty arrays produce no rows

If a row contains an empty array and you try to unwrap it, nothing comes out. The engine doesn’t return a NULL or a placeholder. It skips the row completely, that’s exactly how UNNEST behaves when it has nothing to work with.

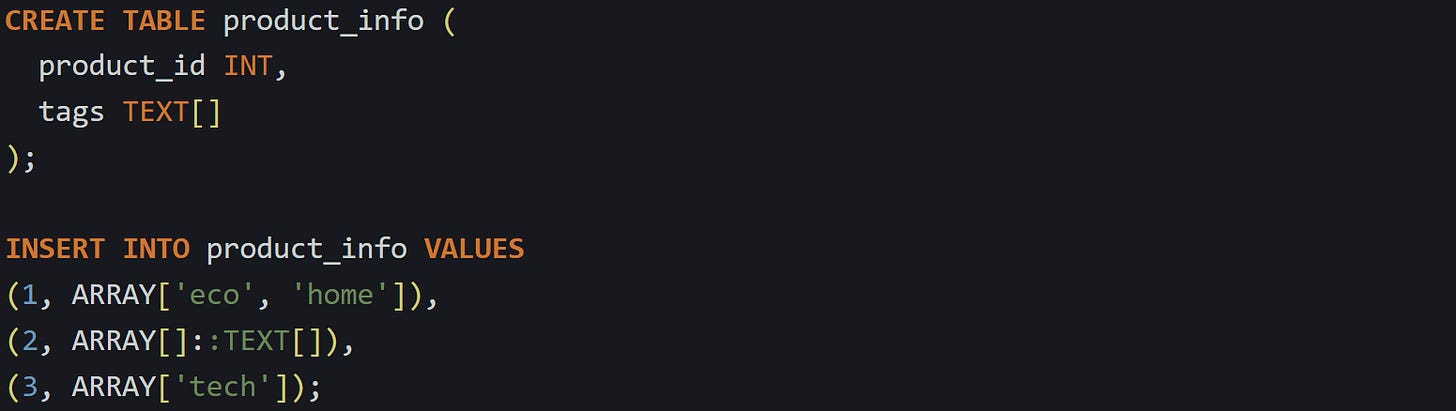

Here’s a simple case. You have a table that tracks product categories, where each product may belong to several tags:

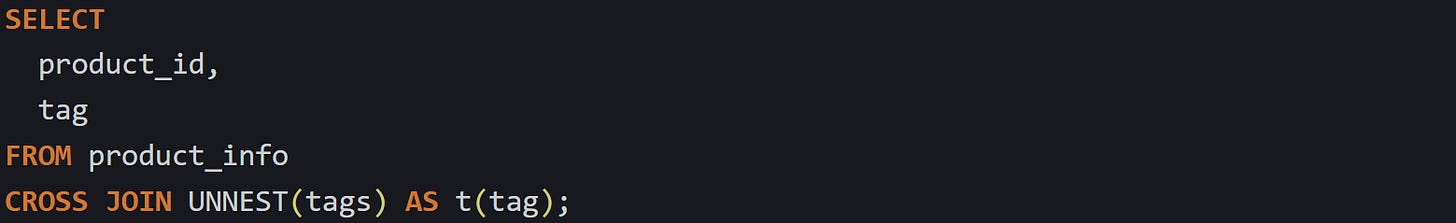

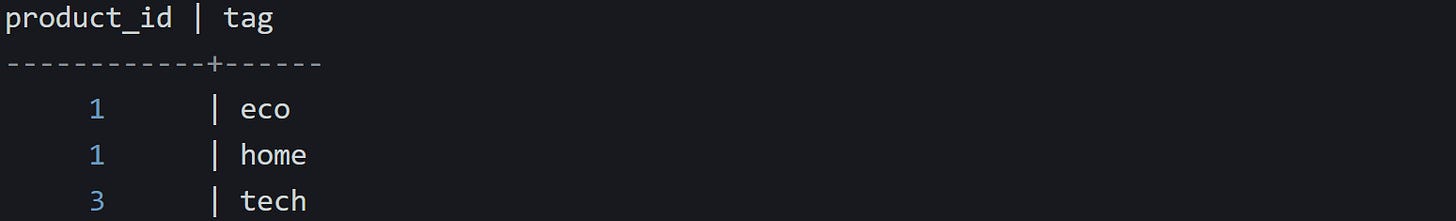

Now flatten the tags:

And the result:

Product 2 is gone. Its array was empty, so UNNEST returned nothing, and CROSS JOIN had nothing to attach to. This can throw things off when you’re expecting every product to show up in the result. If you need that row to stay visible, you can use a lateral join that keeps the original row and adds a NULL if there’s nothing to unwrap.

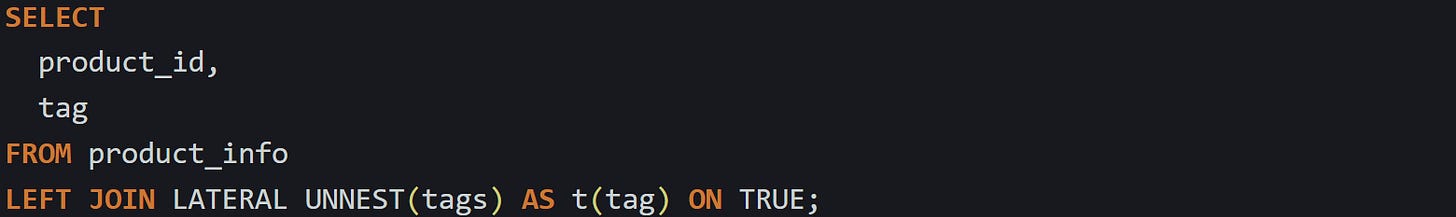

Here’s how that works:

Now you get this:

This keeps all rows from the table, even when the array is empty. It adds a NULL in place of the missing tag so you can still see that the product was there. That makes totals easier to match, or joins more consistent later on.

NULL arrays behave differently

Empty arrays don’t return any rows, but at least they exist. A NULL array is missing entirely. SQL sees it as an unknown value, so it doesn’t try to unwrap anything and just skips it.

Now, let’s update the table and give product 4 a NULL in the tags column:

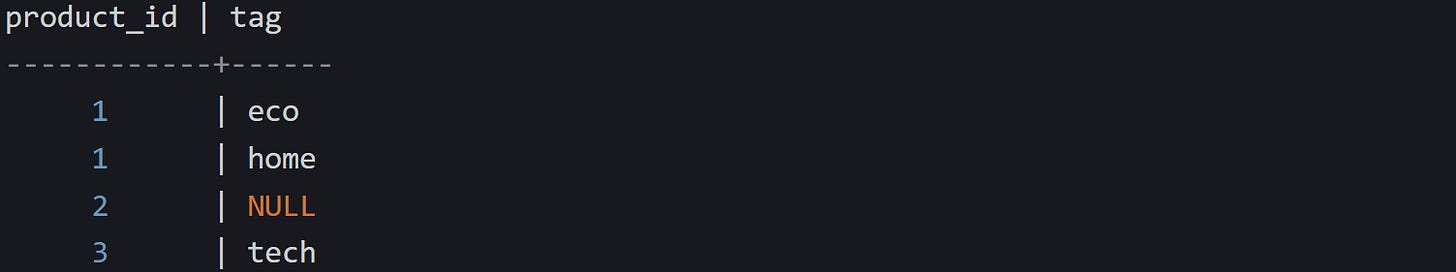

Run the same flattening query:

And product 4 disappears just like product 2. But the reason is different. Here, the array didn’t exist, so the function had nothing to call. SQL doesn’t return an error. It just returns nothing at all.

You can make this easier to handle by treating NULL arrays as if they were empty. COALESCE lets you do that by replacing the NULL with an empty array before UNNEST runs.

Try this:

Now product 4 behaves the same way as product 2. It’s skipped quietly if it has no values, without causing an error or returning broken output. You get a cleaner result that still respects missing data.

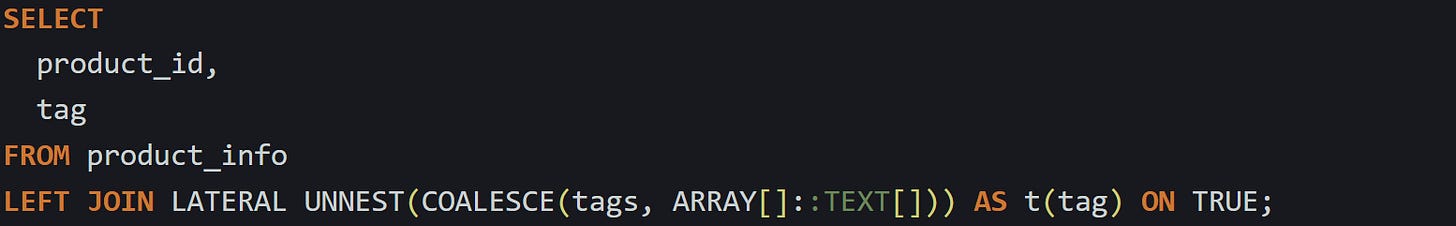

If you want to keep every row no matter what, combine COALESCE with a lateral join:

This gives a full picture. Every product appears. If the tags are missing or empty, tag shows up as NULL. If the array has values, you get a row for each one. That makes the output reliable and predictable no matter how the data looks. SQL doesn’t try to guess what you meant. It evaluates what’s there and gives results based on that. If there’s something to unpack, it will. If not, it won’t. With a few small changes, you can tell it how to treat the edge cases so they behave the same as the rest.

Conclusion

Flattening arrays with CROSS JOIN and UNNEST works by turning each item in the array into its own row and repeating the rest of the data to match. SQL handles this through a mix of table function behavior and row-by-row processing, which makes the unpacking reliable and direct. Empty arrays and NULL values follow their own rules, but with the right join and a small adjustment like COALESCE, you stay in control of what shows up in the result. It’s a useful pattern when one column holds a list and you need each part of it to work like real rows.