Floating point math in C tends to confuse beginners, and even developers who feel comfortable with integers and basic arithmetic aren’t immune. Decimal values that look tidy in source code can print with extra digits, comparisons that seem obviously true can fail, and tiny rounding errors can build up across longer calculations. All of this comes from the way float and double store bits in memory and from the IEEE 754 format that represents real numbers in binary on nearly every modern system.

Floating Point Storage In C

In C, floating point values rely on a small set of types and a specific binary layout that most compilers follow. Values that you write as decimal literals in source code end up as binary fractions in memory, and that mapping is what gives float and double their ranges and precision limits. The language standard talks about minimum ranges and digit counts through macros in <float.h>, and most common platforms follow the IEEE 754 formats for those types. When you see how the bits are arranged, a lot of floating point behavior starts to look predictable instead of mysterious.

Float Double Types In C

C treats float, double, and long double as distinct real number types, and the header <float.h> gives numeric limits for each of them. That header defines macros such as FLT_MIN, FLT_MAX, and FLT_DIG for float, along with DBL_* and LDBL_* variants for the other two types. The macros tell you the smallest positive normalized value and the largest finite value for each type, how many base-10 digits you can trust, and how many base-2 digits sit in the fraction. If you want the smallest positive value including subnormals, look at FLT_TRUE_MIN, DBL_TRUE_MIN, and LDBL_TRUE_MIN when they exist. The standard does not force any particular bit layout, but it does require that float cannot be more precise than double, and double cannot be more precise than long double.

On almost all desktop and server platforms, float matches IEEE 754 binary32 and double matches IEEE 754 binary64. That pairing gives float about 6 to 9 decimal digits of precision and double about 15 to 17. The wider double type also spans a larger exponent range, so it can represent very small and very large magnitudes that do not fit into float. Long double can vary across implementations, sometimes matching double and sometimes holding more bits.

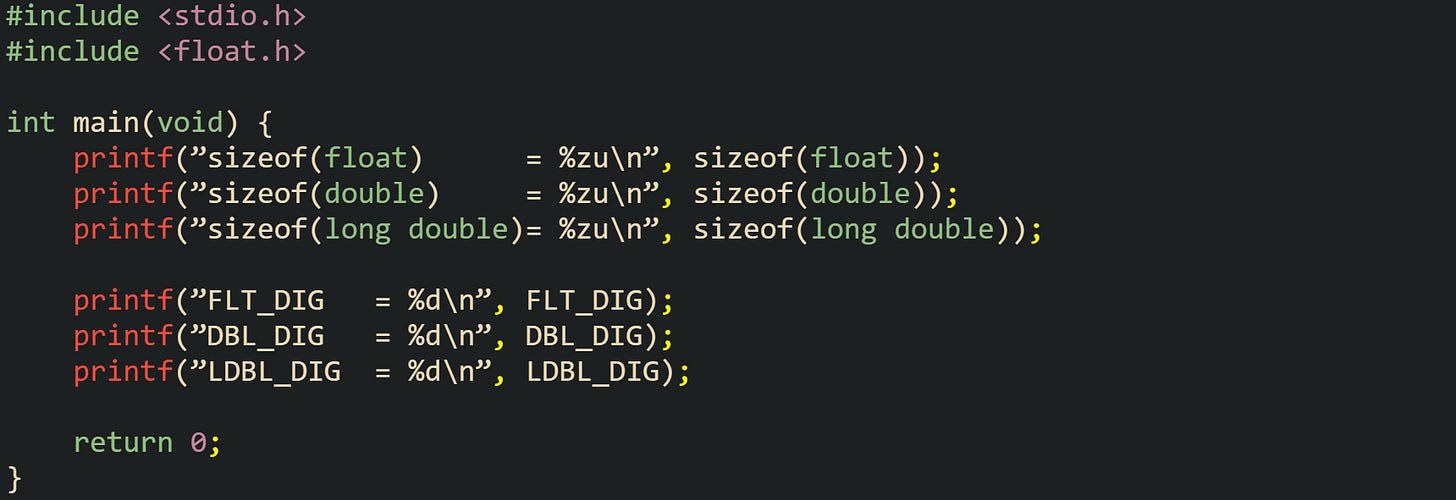

This code prints out sizes and decimal digit counts so you can see how a particular compiler maps these types:

Running that code gives a quick view of how wide each type is on that environment and how many decimal digits you can safely keep for round-trip conversions through text.

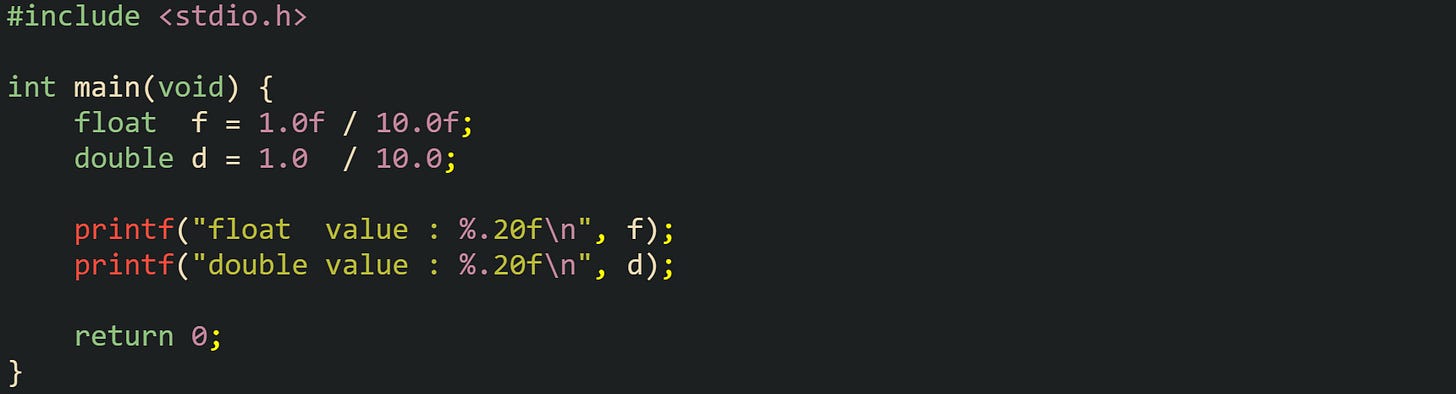

Precision differences stand out when the same mathematical value is stored in both float and double. Let’s see how that looks with an example that stores one tenth in both types and prints them with many decimal places:

Output from this kind of run tends to show that the double line keeps a longer string of correct digits before the rounding error becomes visible. The float line loses accuracy sooner, which comes directly from the smaller number of fraction bits in the IEEE 754 binary32 layout.

IEEE 754 Layout For Float

IEEE 754 binary32, which usually backs the C float type, uses 32 bits split into three fields. One bit holds the sign, eight bits hold a biased exponent, and twenty-three bits hold the stored fraction. Normal numbers in this format have an implicit leading 1 in the fraction, so the actual significand has 24 bits of precision even though only 23 appear in memory. The exponent uses a bias of 127, so a stored exponent value of 127 corresponds to a true exponent of 0.

The value of a finite, normal binary32 number can be written as: value = (−1)^sign × 2^(exponent − 127) × 1.fraction_bits.

Special combinations of exponent and fraction bits cover zeros, infinities, and NaNs. When the exponent is all zeros with a fraction of all zeros, the value encodes positive or negative zero, depending on the sign bit. The same exponent with a nonzero fraction yields subnormal values that sit very close to zero and give a gradual underflow instead of an abrupt jump to zero. If the exponent is all ones with a fraction of all zeros, the value represents positive or negative infinity, and the same exponent with a nonzero fraction encodes NaN values that stand for results like 0/0.

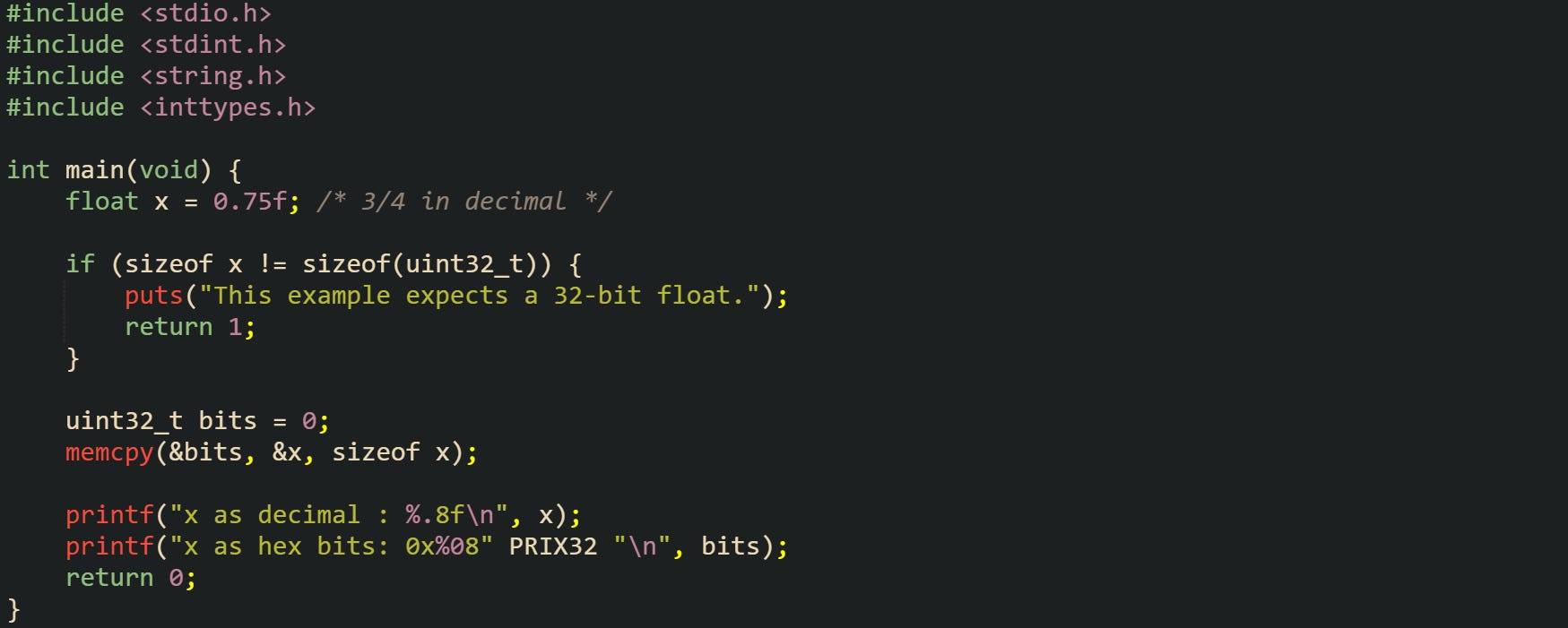

Inspecting the raw bits for a float helps connect this theory with data you can see. When your platform uses IEEE 754 binary32 for float (so sizeof(float) == 4), you can copy the bytes into a uint32_t and print that integer in hexadecimal:

The value 0.75 has an exact representation in binary, so the arrangement of bits maps neatly to a specific exponent and fraction. Comparing the hexadecimal bits against an IEEE 754 binary32 layout table lets you see the sign bit, the biased exponent, and the stored fraction field for this float value. That connection between the printed hex value and the mathematical form sign × 2^exponent × significand is the bridge from raw bytes to numeric behavior.

IEEE 754 Layout For Double

IEEE 754 binary64, which usually matches the C double type, extends the same structure to 64 bits. One bit still holds the sign, eleven bits hold the biased exponent, and fifty-two bits hold the saved fraction. Normal values again have an implicit leading 1 in the significand, so the precision reaches 53 bits even though only 52 are stored. The exponent uses a bias of 1023, so a stored exponent of 1023 represents a true exponent of 0.

Finite, normal double values follow a similar expression: value = (−1)^sign × 2^(exponent − 1023) × 1.fraction_bits.

Special exponent combinations mirror the float case. All zeros in the exponent with a zero fraction give signed zeros, while the same exponent with a nonzero fraction yields subnormal values. All ones in the exponent with a zero fraction encode infinities, and all ones with a nonzero fraction encode NaNs. That structure lets arithmetic operations produce results for overflow, division by zero, and invalid operations in a consistent way across different implementations.

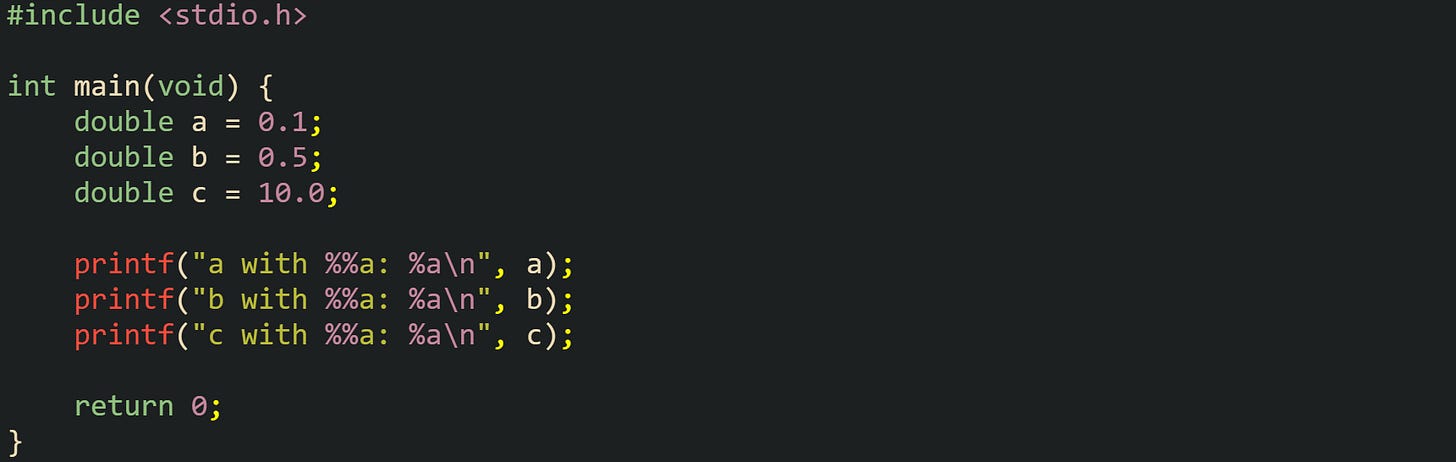

A practical way to see how double stores certain literals is to print them with the %a format from printf. That format writes the value as a hexadecimal significand with a binary exponent, which lines up closely with the IEEE 754 representation:

Hexadecimal output like this reveals exactly which binary fraction sits behind each decimal literal. Values such as 0.5 come out with tidy powers of two in the exponent, while values such as 0.1 show a more complicated fraction in hex, which reflects the fact that they do not have finite binary expansions.

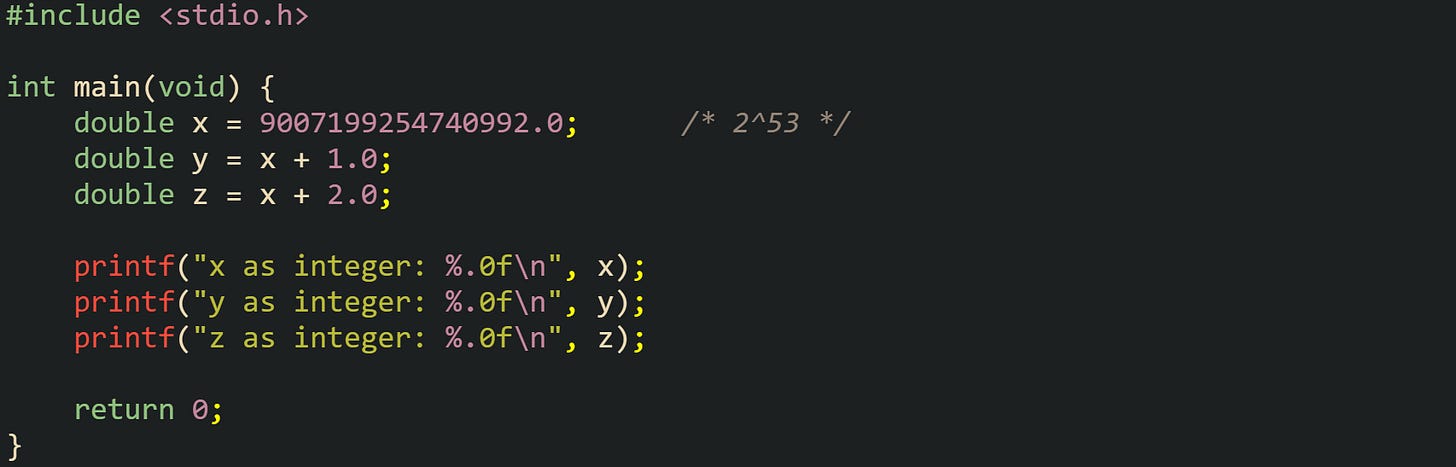

One important property of binary64 is how it handles integers. All integers from 0 up to 2⁵³ can be represented exactly in a double. Past that point, not every integer can be stored without loss, because the gap between neighboring representable values grows larger than 1. This example code marks that boundary:

Printing these values as integers makes the jump visible. The values around 2⁵³ no longer sit exactly one unit apart in double space, and some neighboring integers share the same binary64 representation. That behavior follows directly from the fixed 53-bit precision of the significand and the way IEEE 754 distributes representable values across the number line.

Common Behaviors In Floating Point Math

Rounding and comparison rules drive most of the surprises that new C developers run into with floating point values. Decimal literals that seem harmless on the page turn into nearby binary fractions, and the small difference between the value you expect and the value stored in memory can show up during arithmetic, loops, and comparisons. Output formatting choices add another layer, because printf can either reveal those tiny gaps or hide them behind a short decimal string. The same IEEE 754 layout that gives float and double their wide range also limits how precisely they can represent base-10 numbers, and that tradeoff shows up in day-to-day code.

How Rounding Errors Show Up

Binary floating point stores numbers as sums of negative powers of two. That structure works perfectly for values like one half or one quarter, but a decimal value such as one tenth requires an infinite binary fraction, so the stored value ends up as the closest representable neighbor. The same idea applies to many other decimal fractions that look tidy in base 10 but have no finite expansion in base 2.

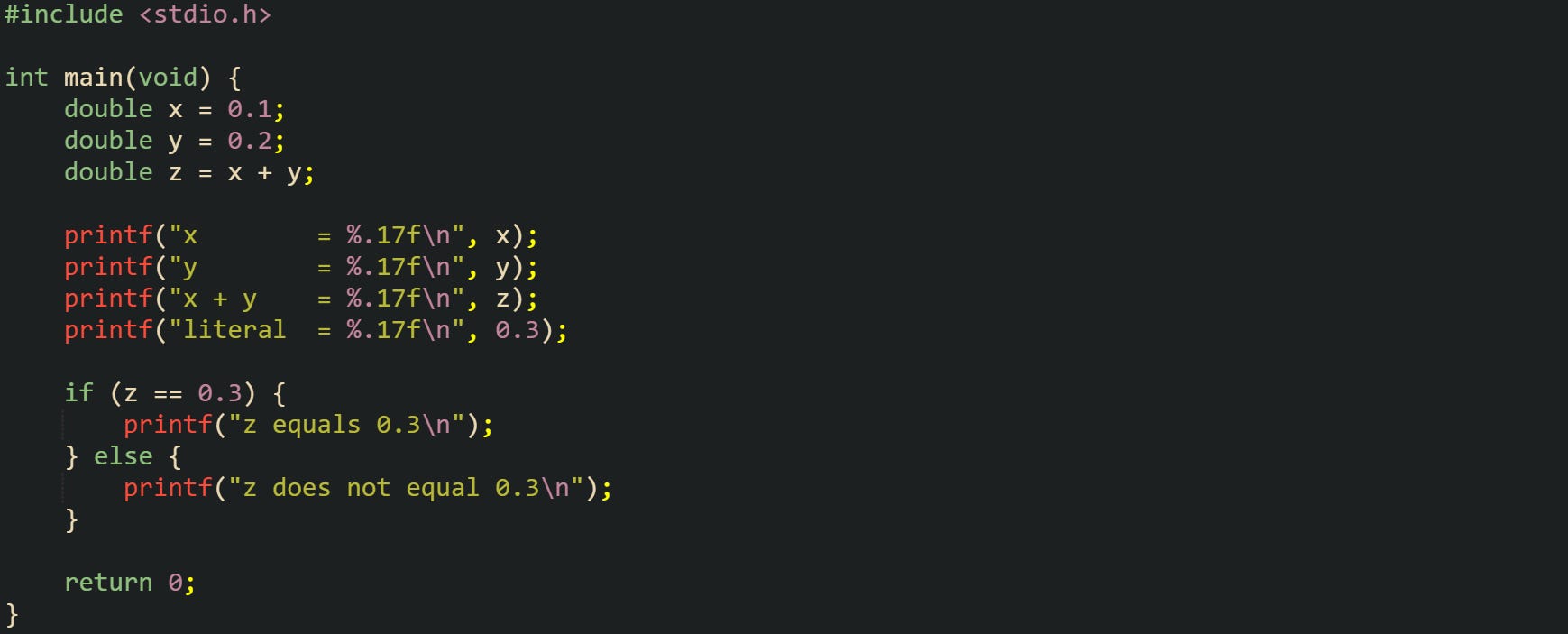

One of the most common examples uses 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3. Those decimal literals do not map exactly to binary32 or binary64, so they land on nearby values instead. That tiny offset is enough to affect equality comparisons and printed output when the format string shows enough digits.

This run typically prints x and y as values close to 0.10000000000000001 and 0.20000000000000001, while x + y appears near 0.30000000000000004 and the separate literal 0.3 appears just below 0.3. The comparison at the end reports that z is not equal to 0.3, which surprises newcomers who expect exact base-10 behavior.

The spacing between neighboring floating point values is not constant across the number line. Near 1.0, double precision values sit very close to one another, while far from 1.0 those gaps widen. Macros such as FLT_EPSILON and DBL_EPSILON from <float.h> give the distance between 1.0 and the next larger representable value for float and double. That distance acts as a local step size for the format near 1.0.

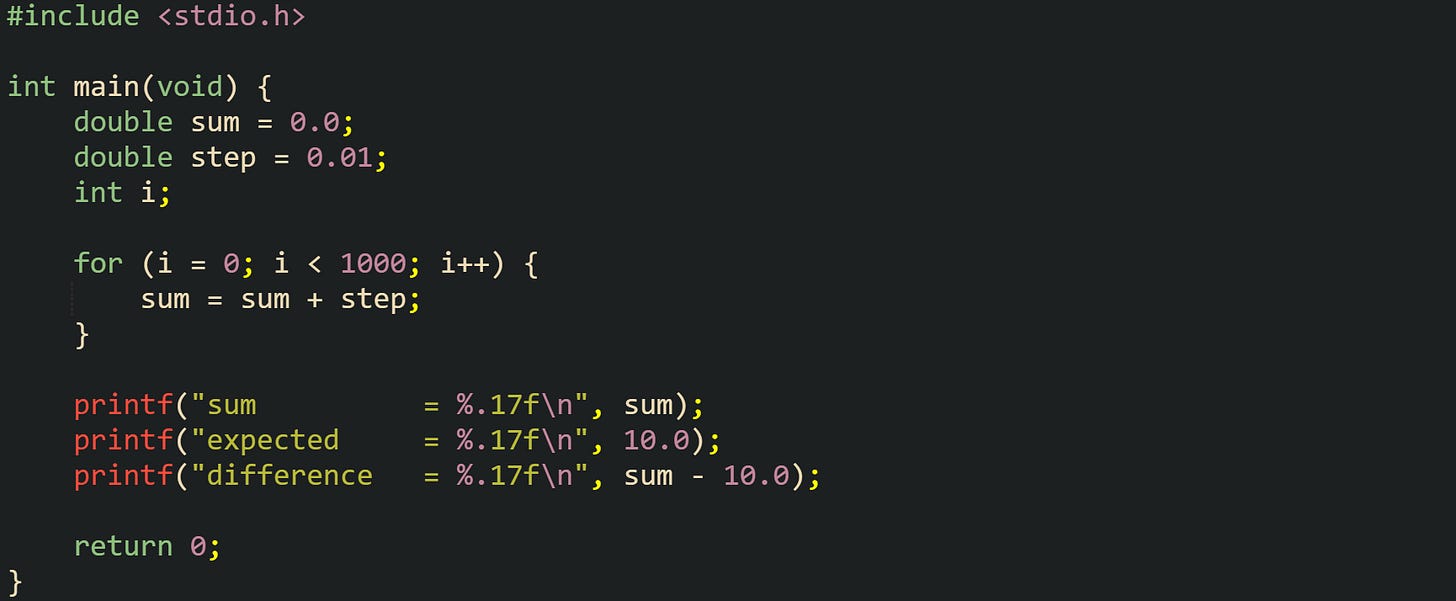

Rounding effects accumulate when a loop adds a small value to a running total. After enough iterations, the total can drift a little from the exact arithmetic result, because each addition rounds to the nearest representable value.

Output from this example tends to show a sum value very close to 10, but not exactly equal. The reported difference lands near a small positive or negative number, often on the order of 1e-13 for double. Every addition in the loop rounds to the nearest representable value, and the small rounding errors do not cancel perfectly, so the final result carries a tiny mismatch compared with exact arithmetic on real numbers.

Subnormal numbers form another corner of rounding behavior. When a value gets very close to zero, the exponent reaches its minimum, and further scaling happens by shifting bits inside the fraction field. That region near zero has fewer effective precision bits, so relative error grows, and operations that push values into or out of the subnormal range can change precision in ways that catch people off guard. For everyday application work, this mostly appears as values snapping to zero a little earlier than expected when magnitudes are extremely small.

Comparisons Printing Habits For Beginners

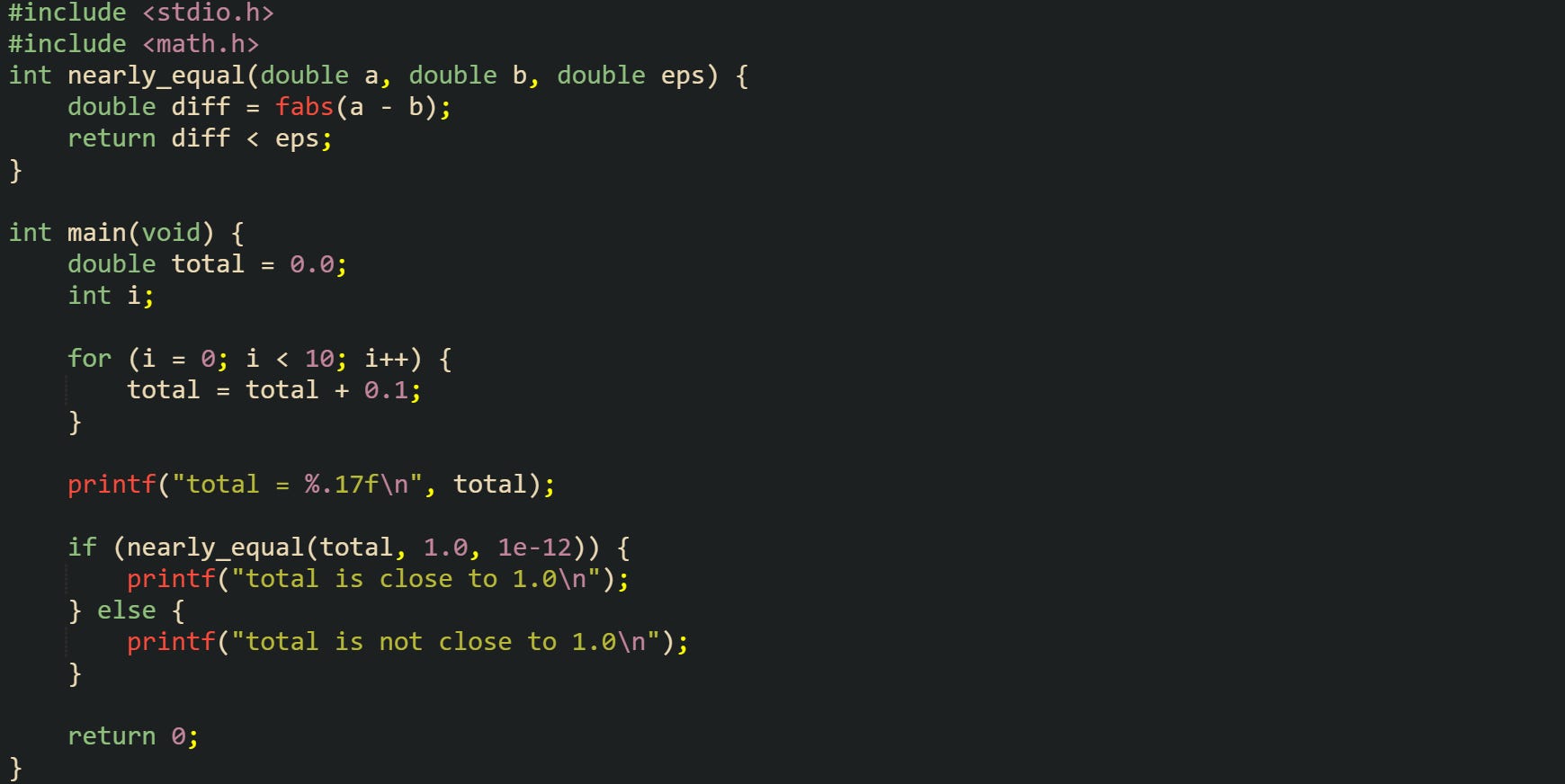

Equality checks that work perfectly for integers tend to fail for floating point values that involve arithmetic. Even when printed values look similar, the bit patterns can differ enough that == returns false. Instead of asking for perfect equality, it is common to check whether two numbers are close within some tolerance that fits the scale of the problem.

One simple good habit is to compare the absolute difference between two numbers to a tiny threshold, sometimes called epsilon in code. The standard library provides fabs in <math.h> to compute the absolute value of a double. Picking an epsilon value that fits your data range is important because too large hides real differences, and too small lets rounding noise trigger inequality.

This style of comparison treats two values as equal when they differ by less than eps. For values near 1.0, an epsilon like 1e-12 works well with double precision. For values around one million or one billion, a relative test that scales the tolerance with the magnitude may be more suitable, for example by comparing fabs(a - b) against eps * fabs(b) plus a small fixed term.

Ordering comparisons can also benefit from a tolerance, especially when a result hovers near a boundary. A condition such as x <= limit can be replaced with x <= limit + eps to avoid random inequality caused by tiny rounding error right near the cut-off value. The same idea applies to lower bounds. These habits do not change how the hardware computes, but they steer control flow away from brittle equality checks.

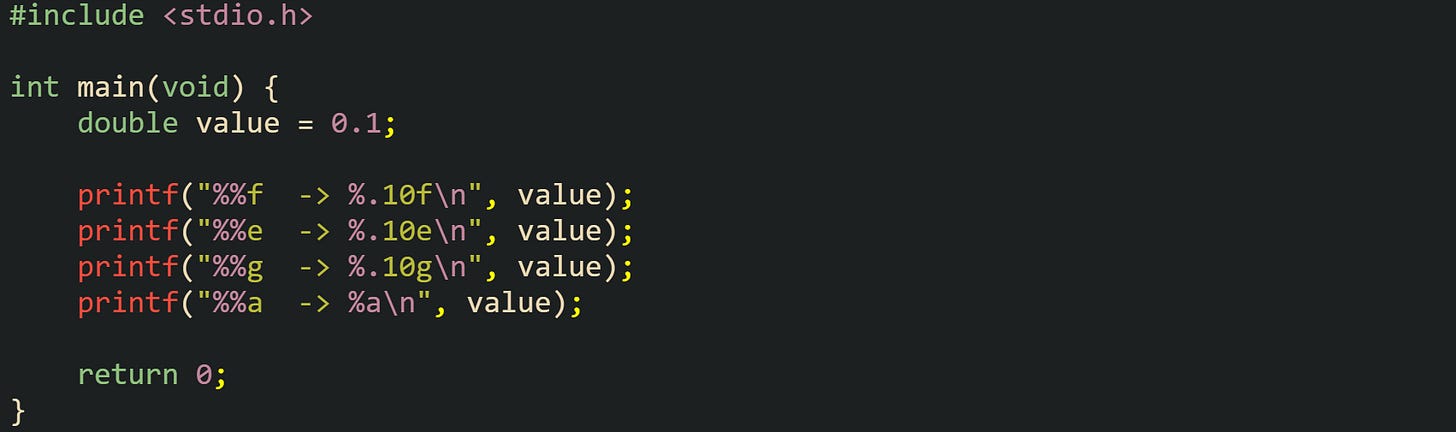

Printing behavior is closely tied to how humans perceive floating point values. Debugging output tends to use formats that reveal the stored value, while user-facing output prefers shorter decimal strings that hide small binary artifacts. The printf family in C supports several floating formats. "%f" prints a fixed number of digits after the decimal point, "%e" prints in scientific notation, "%g" switches between the two and trims unnecessary zeros, and "%a" prints a hexadecimal fraction with a binary exponent that maps directly to the IEEE 754 representation.

Looking at this output gives a sense of how the same stored value can appear very different depending on the format string. The %a form in particular lays out the significand and exponent in a way that matches the binary64 layout, which helps when you want to study rounding behavior closely.

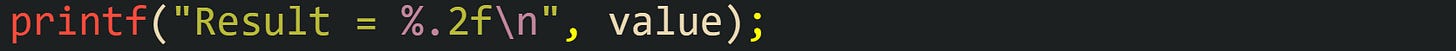

Daily application code usually prints fewer digits for users. Take this for example:

That rounds to two decimal places, which hides tiny binary errors that arise from representing decimal fractions in binary form. Internal calculations still happen in full double precision, but the final display trims the extra digits that are not helpful to a reader.

Input follows similar rules. Functions like scanf with %f and %lf convert decimal text into float and double, rounding to the nearest representable value in the target format. That means feeding the same decimal string back into scanf after printing with enough digits will usually reconstruct the original binary value, as long as the format used for output carried enough precision for a round trip.

Conclusion

Floating point math in C is based on IEEE 754 layouts for float and double, where a sign bit, biased exponent, and fraction field combine to encode real numbers in binary form. That fixed structure explains why decimal fractions such as 0.1 map to nearby representable values, how small rounding errors can accumulate in iterative arithmetic, and why equality checks with == frequently fail after computations. Comparison strategies built around tolerances and printf formats such as %f, %g, and %a follow directly from these mechanics and align output and control flow with the actual bit patterns stored in float and double.