Function calls are at the center of almost every C codebase. Each call hands control from one function to the next, passes arguments, allocates space for local variables, and returns a value when it finishes. This behavior rests on a model that links the C language rules with a specific platform Application Binary Interface (ABI). The language standard describes what compiled C code can rely on at the source level, while the ABI for a given architecture and operating system lays out how arguments, return values, and stack frames move through registers and memory.

Function Call Model in C

Function calls in C live at two levels at the same time. At the source level you write a function type, a name, a parameter list, and a body, and calls appear as expressions that transfer control to that body. Beneath that surface, the compiler maps those rules onto a specific calling convention so that arguments, parameters, and return values line up correctly between caller and callee.

Function Declarations, Definitions

Every C function has a type that combines a return type with an ordered sequence of parameter types. The declaration introduces that type so the compiler can check calls for compatibility, and the definition supplies the body that will execute when the function is called.

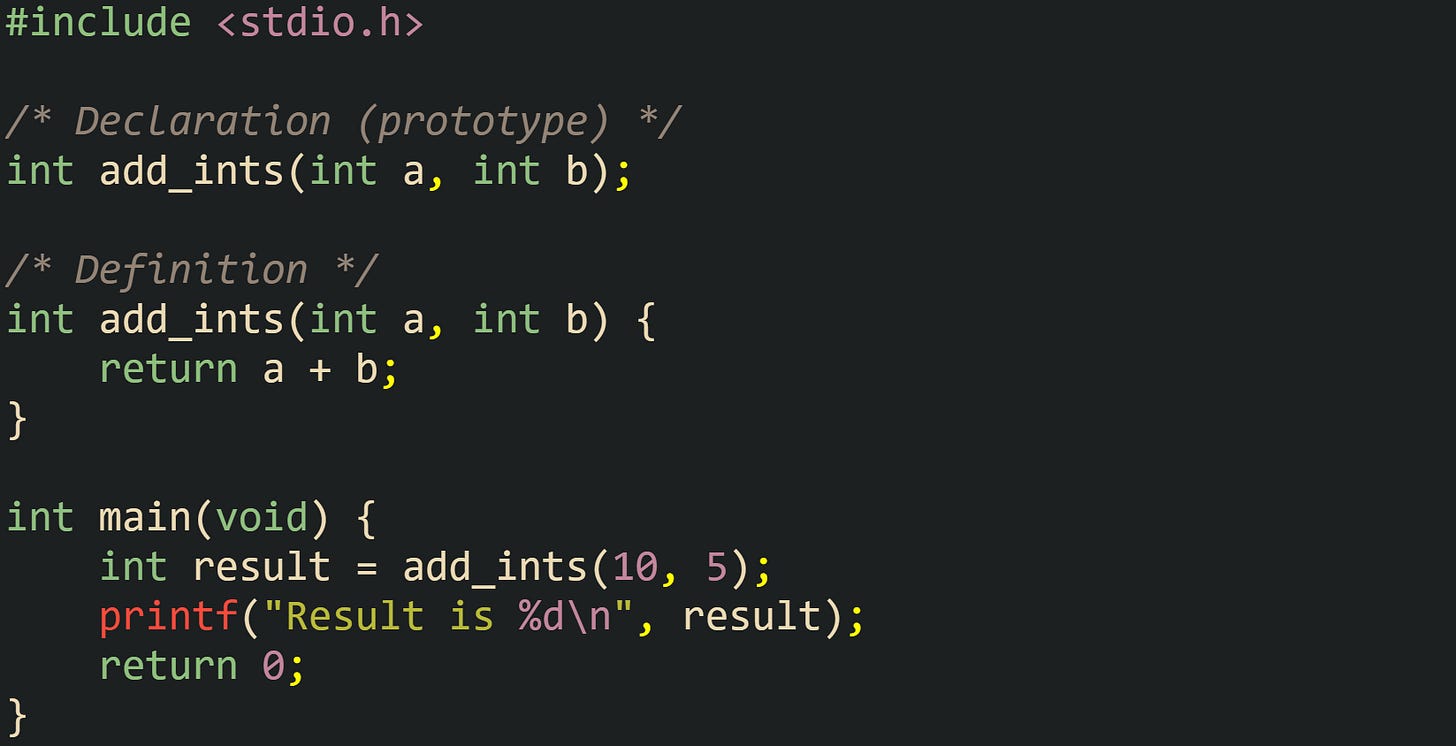

This small example helps visually ground the idea of a prototype and a matching definition:

This pair of declaration and definition tells the compiler that add_ints takes two int parameters and yields an int value. The declaration gives the function type, and the definition must match that type exactly. Parameter names such as a and b help people read the header but do not affect the type, so int add_ints(int, int); declares exactly the same function type as the version with names. When the compiler sees add_ints(10, 5), it can confirm that both arguments are compatible with the parameter list and that the call will produce an int result.

Keeping the prototype visible at the point of call matters for modern C. Under current C standards, a program that calls a function in a source file without any declaration in scope is not a conforming program, because the compiler has no reliable information about the parameter types or the return type. Typical practice is to place function prototypes in header files and include those headers from every translation unit that either defines or calls the function, which keeps types aligned across the whole codebase.

Older C code sometimes relies on an older standard form of function definition where parameter types appear after the function header. Many compilers still accept that form, but C23 removed it, so new code should stick with prototype style definitions.

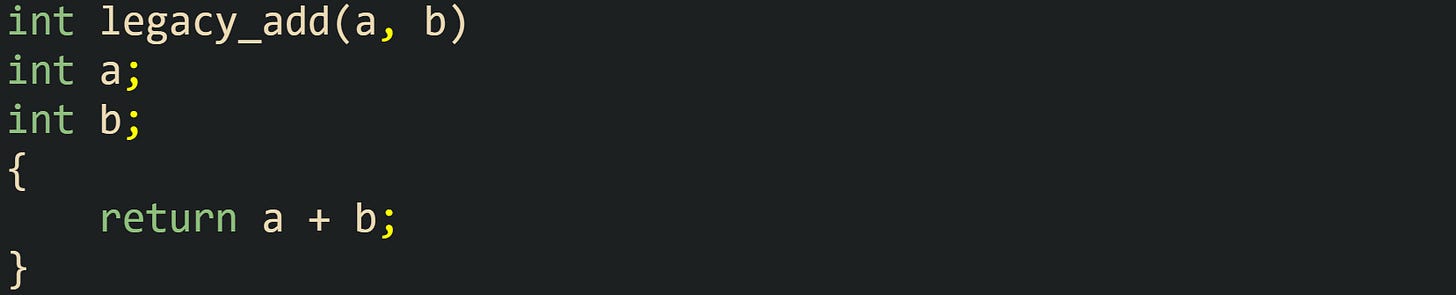

Legacy syntax from older projects can look like this:

This form describes legacy_add as a function that takes two int parameters and returns an int, but the syntax splits the parameter list from the parameter declarations. Modern C places parameter types directly inside the parentheses in the function header, which makes the function type easier to read and gives the compiler all the type information at one point. When working with mixed codebases where some files still use this style, developers typically migrate toward prototypes as code is updated, so every call site has an explicit declaration available.

Argument Evaluation, Parameter Passing

At the language level, a function call is an expression where a function designator or function pointer appears before a parenthesized list of argument expressions. Those argument expressions are evaluated first, their results are converted to parameter types, and then execution continues in the body of the called function with parameters initialized to those converted values.

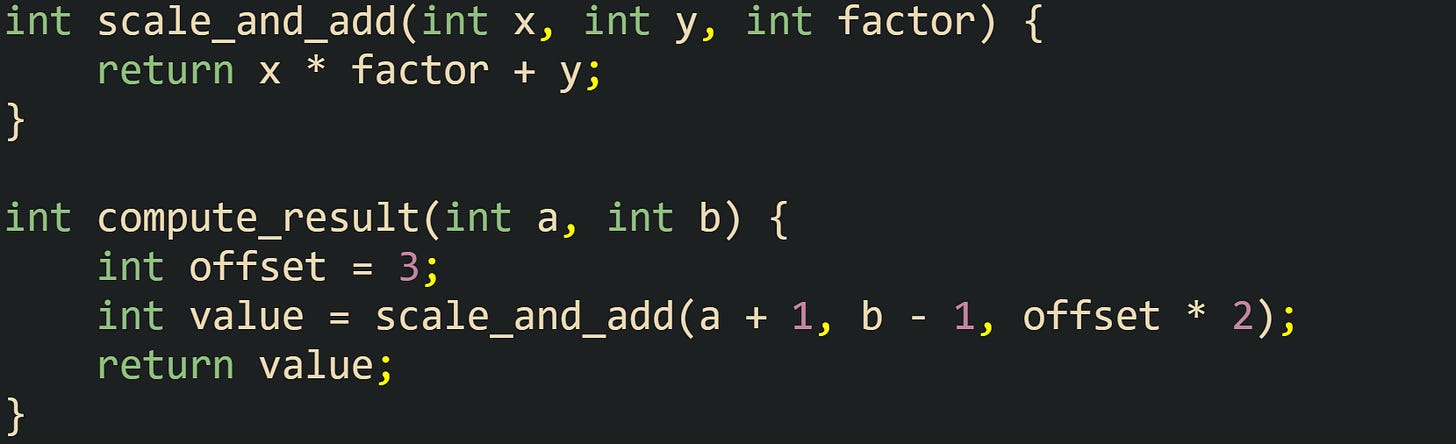

Take this short numerical example that makes the evaluation steps easier to see:

The call to scale_and_add uses three expressions as arguments. Each expression is evaluated completely before the body of scale_and_add begins. The C standard allows the compiler to choose the order in which those three expressions are evaluated, so one implementation can evaluate a + 1 first, while another can start with offset * 2. All that matters at the language level is that every argument expression is finished before control enters the called function and that side effects from those expressions have taken place.

This flexibility in evaluation order becomes important when argument expressions modify shared state. Code where one variable is updated more than once inside a single call can fall outside the rules the standard guarantees.

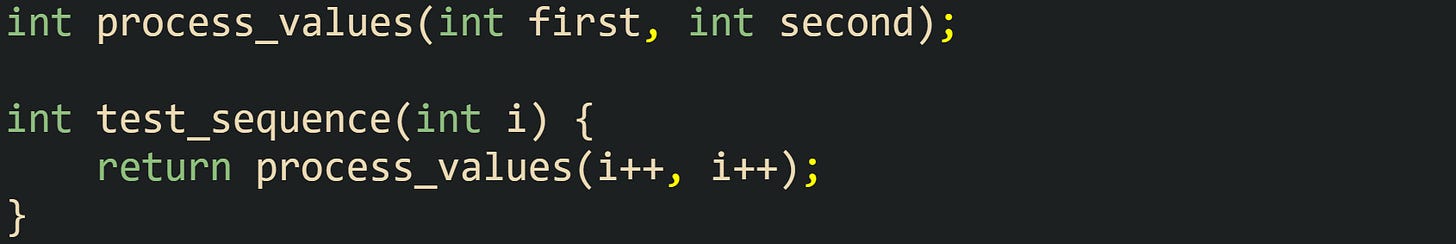

Side effects on a single variable can be seen in code like this:

Both arguments to process_values update i, and because the two increments are not sequenced with respect to each other, the C standard treats this call as undefined behavior rather than as a valid call with an unspecified order. Code that relies on that expression is not valid C, so the compiler is free to assume it never happens and the program can misbehave in ways that go beyond returning different values from test_sequence. Safer code in that situation updates i in a separate statement, or uses distinct temporary variables, so each argument to a function call touches shared state no more than one time.

Argument values themselves pass through conversion rules before becoming parameter values. Arithmetic types follow the integer promotions and usual arithmetic conversions, pointers can convert to compatible pointer types where the standard allows that, and qualifiers such as const follow the qualification rules. Function types that end with a variable argument section, as in the printf declaration int printf(const char *fmt, /* variable arguments */);, treat arguments in that trailing part with special promotion rules so float values are promoted to double and small integer types such as char or short are promoted to int. From the body of the function, parameters behave like auto variables that have already received their initial values before the first line of the body executes.

Return Values From The C Language View

From the language perspective, a C function either produces a value for its caller or returns no value at all. Functions with a nonvoid return type carry one or more return statements whose expressions can be converted to that type, and callers may store or use the result wherever an expression of that type is permitted. Functions with void result type indicate that no value flows back.

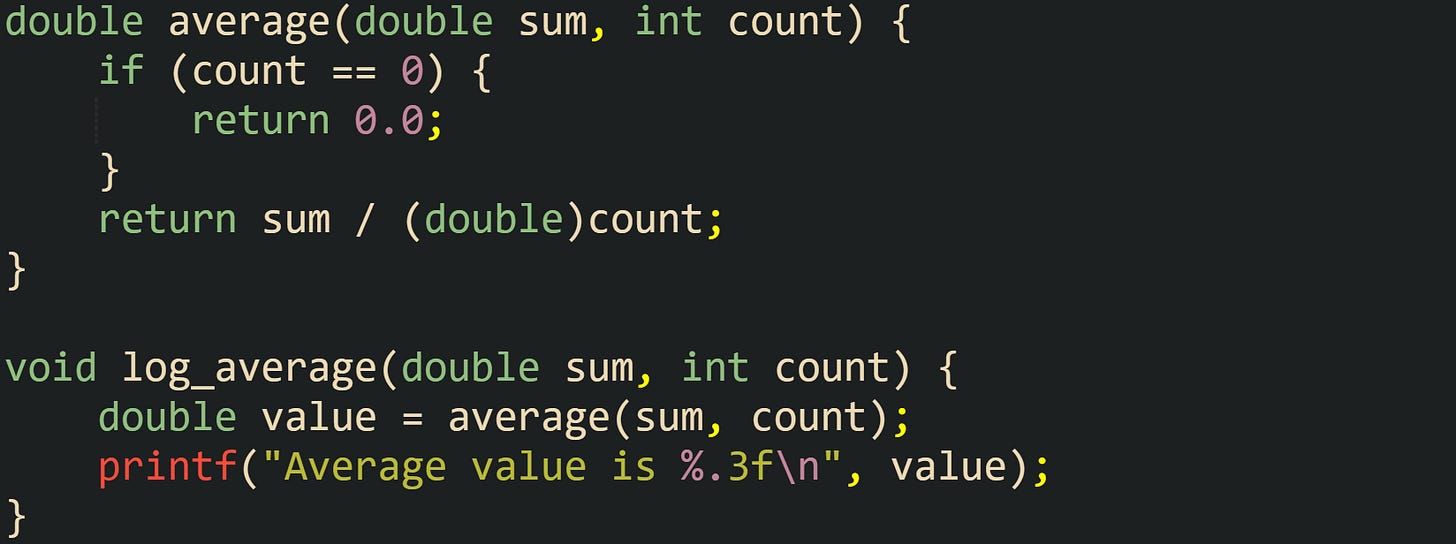

One common case is a numeric result based on parameters:

The function average has return type double, so every return statement in its body must carry an expression that can be converted to double. In the first branch the literal 0.0 already has type double. In the second branch the expression sum / (double)count has type double after the cast, so it also matches the return type. The caller log_average treats average(sum, count) as an expression of type double, assigns that value to value, and passes it along to printf. A function with nonvoid return type that reaches the closing brace of its body without executing a return statement has undefined behavior according to the C standard, so compilers warn about such functions when warnings are enabled. One special case is main, where reaching the end of the function has the same effect as return 0; in modern C standards.

When a function has result type void, it still can perform side effects but cannot contribute a value to expressions. Logging routines give a simple example of void results:

Calls to print_header and print_footer appear as full statements, such as print_header();, and any attempt to assign print_header() to a variable or combine it with arithmetic would be rejected, because the expression has no value. Void functions commonly handle logging, output, or updates to objects that reach them through pointers. C also supports returning large objects by value, such as structures that group multiple fields. From the language point of view this works in the same way as scalar return values, where the function constructs a structure and presents it to the caller as a complete value.

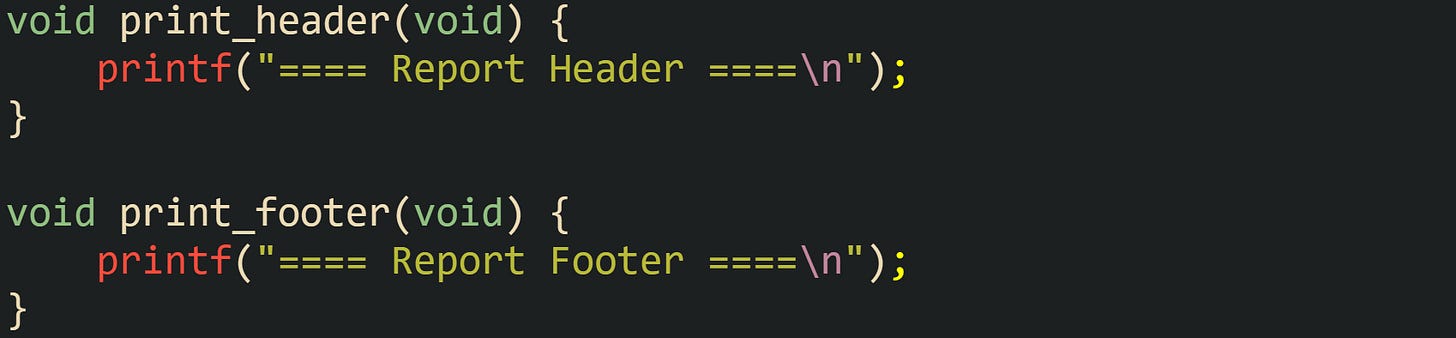

Structure returns in C can take this form:

The make_stats function declares a local Stats object, assigns fields, and returns that object by value. The caller can write Stats report_stats = make_stats(10.0, 25.0, total_sum, total_count); and receive a fully initialized Stats instance. How this value travels back to the caller, whether through registers or through a hidden pointer to caller allocated storage, is outside the language description, but at the C level the guarantee is that the caller obtains a Stats result that matches the values assigned in the function body.

Stack Frames, Calling Conventions, Function Pointers

The C language view of function calls describes arguments, parameters, and return values in terms of types and expressions. Compiled code adds another layer, where every call follows rules laid out by the platform ABI so that different object files and libraries can call one another safely. That lower level view introduces stack frames, register conventions, and rules for how function pointers are used to jump to code addresses that are only known at run time.

Stack Frames For Local Data

Most C implementations keep a call stack in memory where active calls are arranged in a last in, first out order. Each call has a stack frame that holds the bookkeeping data and local storage needed while that function runs. The frame can cover items such as saved registers and the memory reserved for local variables and compiler generated temporaries. The return address can be stored on the stack or kept in a link register and saved to the stack only when needed by the ABI and the compiler.

Consider a function that scans an array and accumulates a sum:

On a typical 64 bit system, the frame for sum_array holds storage for the two local variables total and index, and may also hold saved copies of registers plus any compiler generated temporaries. When sum_array is called, the calling code transfers control to the entry point. The prologue of the function then adjusts the stack pointer to carve out space for the frame and may store a frame pointer to make access to locals easier. Near the end of sum_array, the epilogue restores saved registers, moves the stack pointer back, and branches to the stored return address so that the caller continues executing after the call expression.

Not every function needs the same shape of frame. Extremely small functions can be compiled so that parameters live only in registers and there is no dedicated frame pointer. Recursion and nested calls still work, because each active call reserves its own space on the stack and the return address for each call sits above that frame in memory. When the call tree grows deeper, more frames sit on the stack. Returning from calls unwinds those frames in reverse call order, which matches the way C function calls are written and evaluated.

Local arrays and larger objects extend the same idea. A function that declares a buffer as an array with automatic storage gets a frame large enough to hold that array and the other locals. Accesses to that storage are compiled into stack relative loads and stores. When the function returns, the frame goes away and that storage cannot be used any more, which is why returning a pointer to a local array or a local scalar variable leads to undefined behavior.

Argument Passing In Common ABIs

C source code stays mostly the same across machines, but generated code must follow very specific habits when moving arguments into a call and returning results. Modern platforms publish ABI documents that specify which registers hold the first few arguments, how the stack pointer must be aligned at call time, and which registers a function is allowed to overwrite without saving. Compilers on that platform follow those rules so that binaries compiled at different times and with different settings can still call the same functions and exchange data correctly.

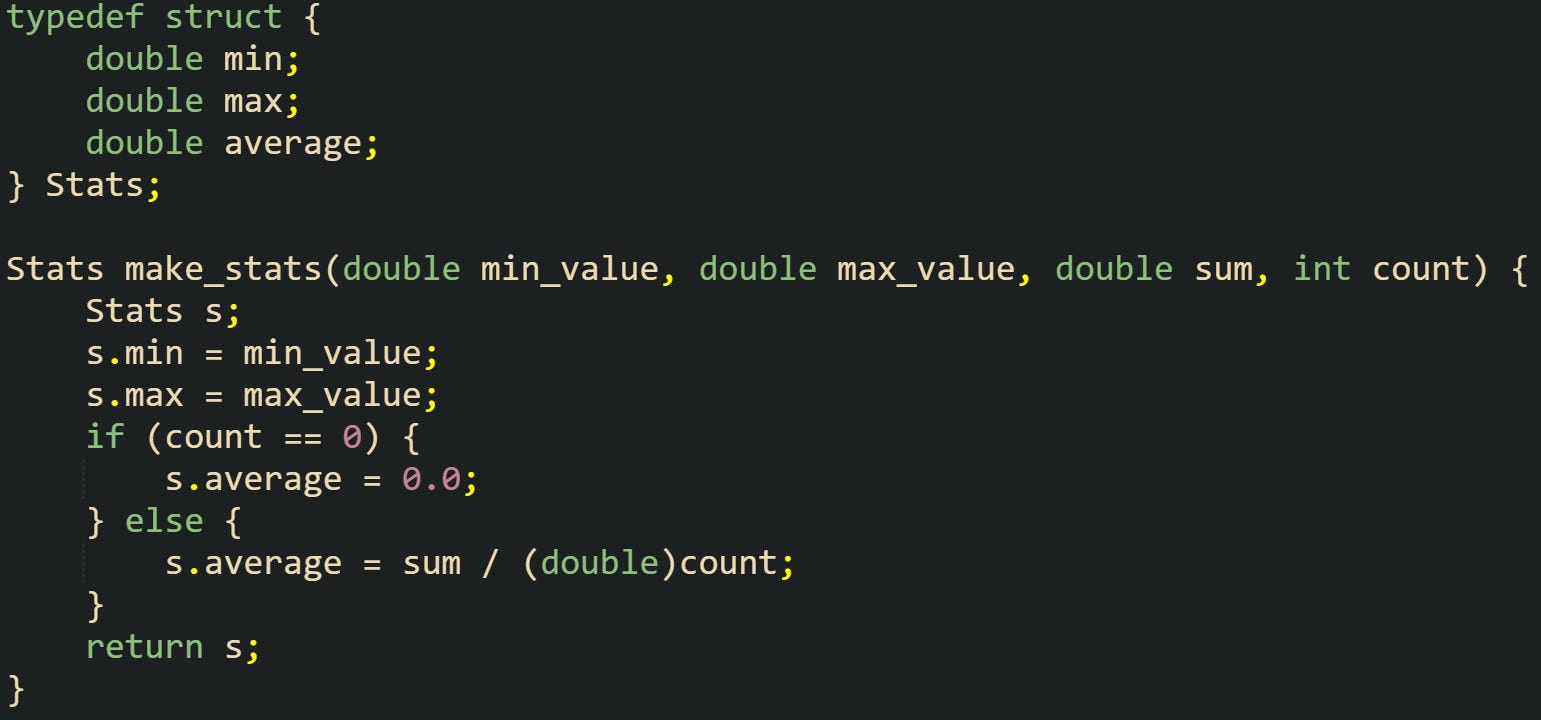

Take this short function with three integer parameters, as it gives a good point of reference:

On a system that follows the System V AMD64 ABI on x86 64 hardware, the caller places x, y, and z into general purpose registers before control enters add_three. At the entry point, the callee treats those registers as holding the parameter values and is free to copy them into stack slots or into other registers as part of its own work. On Windows x64, a different set of registers carry the first four integer or pointer arguments, but the basic idea matches, with a fixed order of registers and a spillover to stack memory if there are more parameters than available registers.

Floating point arguments have similar rules, but use a bank of floating point or SIMD registers on platforms that provide them. When a function has both integer and floating point parameters, the ABI for that platform spells out which registers carry which parameters and how the compiler should assign them. Any arguments that do not fit in the prescribed registers land in stack slots above the current frame, and the callee reads them from those locations. The caller and callee do not need to coordinate manually, because both sides were compiled from C sources through the same ABI rules.

On Arm AArch64 platforms, C functions follow another widely used calling convention. Integer and pointer parameters fill the general purpose registers in order, starting from X0, while floating point values fill vector registers such as V0. Extra arguments again spill to the stack. That layout lets C code compiled on one machine call C code compiled on another machine of the same family and receive arguments in the right registers, even if the binaries were built with different compilers, as long as both compilers honor the ABI description.

Return Values Through Registers, Memory

Return values travel back to the caller by a mix of registers and memory, based on type and size. ABIs divide return types into several groups, such as small integers and pointers, floating point scalars, small aggregates, and larger aggregates that need more storage than fits in a handful of registers.

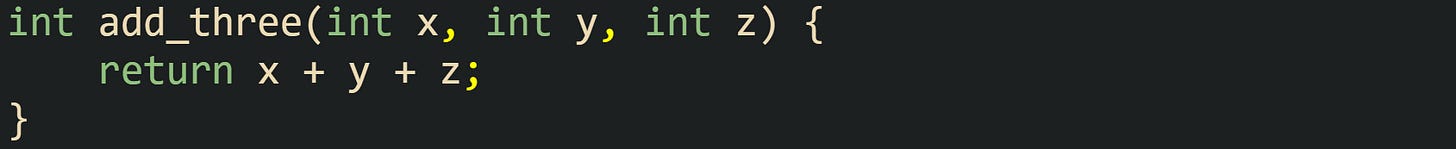

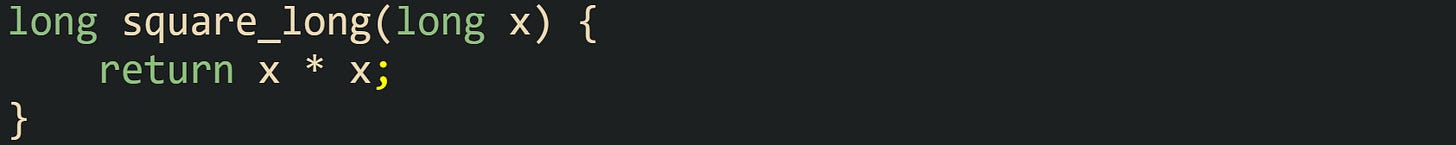

A scalar integer case is the most compact. Now, lets see a function that squares a long integer:

On common 64 bit ABIs, the caller places x in a register before the call and expects the result in a designated return value register. For System V AMD64 and Windows x64, that register is typically RAX. The compiled code for square_long reads the parameter, computes the product, leaves the result in the return register, and executes a return instruction. Control jumps back to the call site, and the caller reads the register that holds the result and continues its own work.

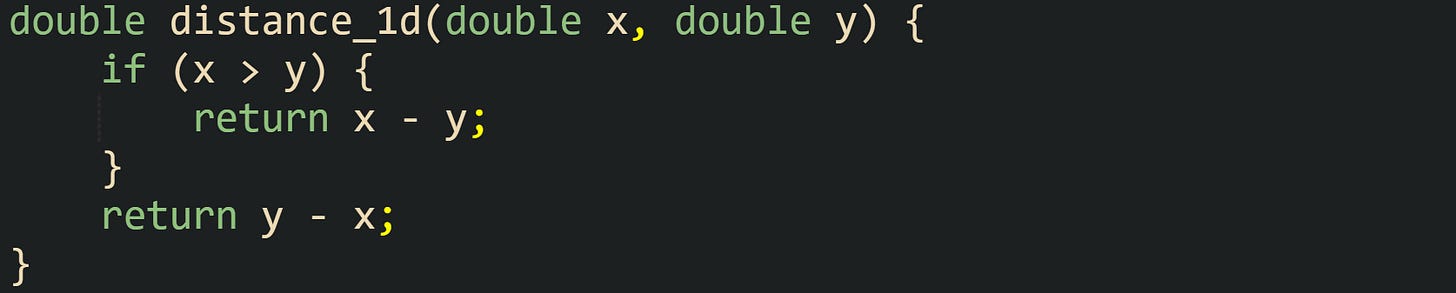

Floating point return values use a separate register bank. Like this function:

This returns its double value in a floating point or vector register that ABI documents specify, such as XMM0 on x86 64 or V0 on AArch64. Callers treat that register as holding the result, so a call expression to distance_1d slots naturally into larger floating point expressions in C.

Aggregates such as structures and unions add a few more branches to the ABI rules. Small aggregates that fit into a limited number of registers can be split across those registers at return time. Larger aggregates use a calling convention trick where the caller passes a hidden pointer to memory reserved for the result, and the callee fills that memory instead of placing the result directly into a register.

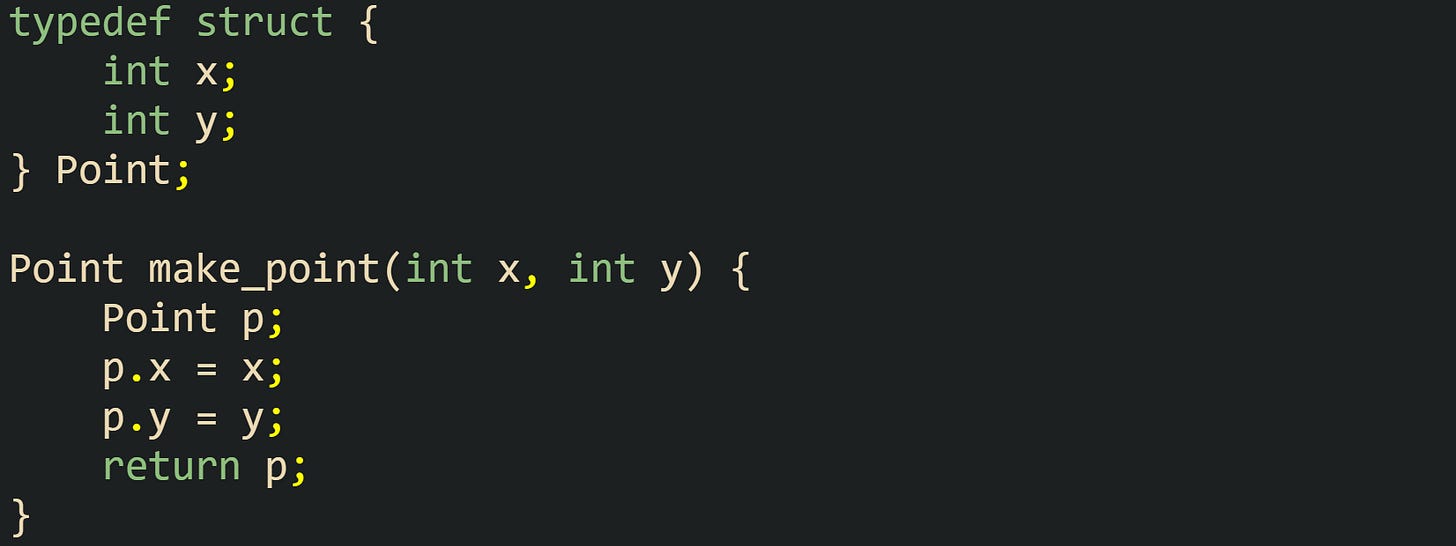

One way to see this from C code is to use a structure that groups multiple values:

To the C caller, make_point acts like any other function. A call like Point p1 = make_point(3, 7); receives a complete Point value. The ABI rules decide if that Point travels back through two integer registers or through a memory buffer referenced by a hidden pointer that the caller sends in. That choice does not change how callers write the code. The only visible behavior is that the fields p.x and p.y hold the values written inside make_point when control returns to the caller.

Very large structures normally return through a hidden caller provided result pointer, so the callee writes into caller storage instead of returning the value only in registers.

Function Pointers Within The Call Model

Function pointers connect C source to ABI call rules in a direct way. A function pointer variable holds a code address that acts as the entry point for a function with a given type. When C code calls through that pointer, the compiler uses the same argument passing rules and return value rules as a direct call, but arranges the branch as an indirect jump to the stored address.

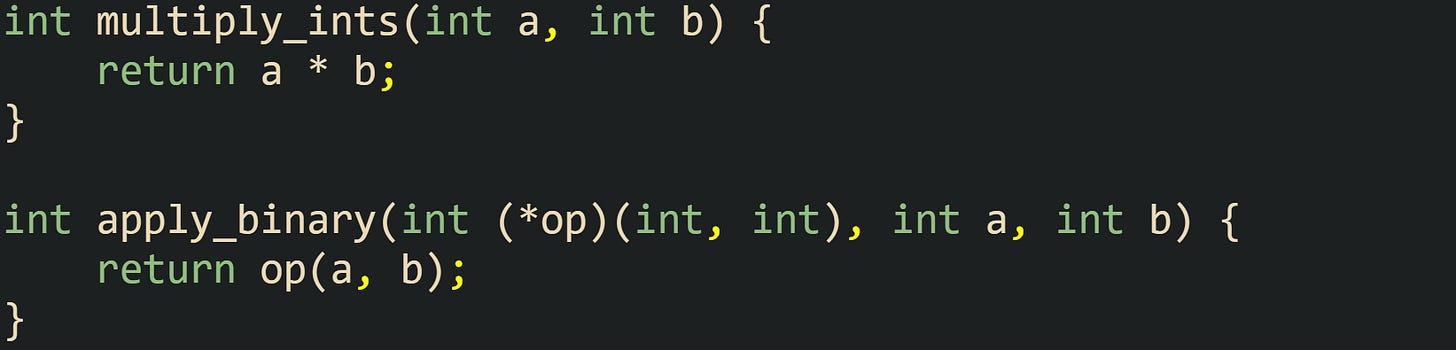

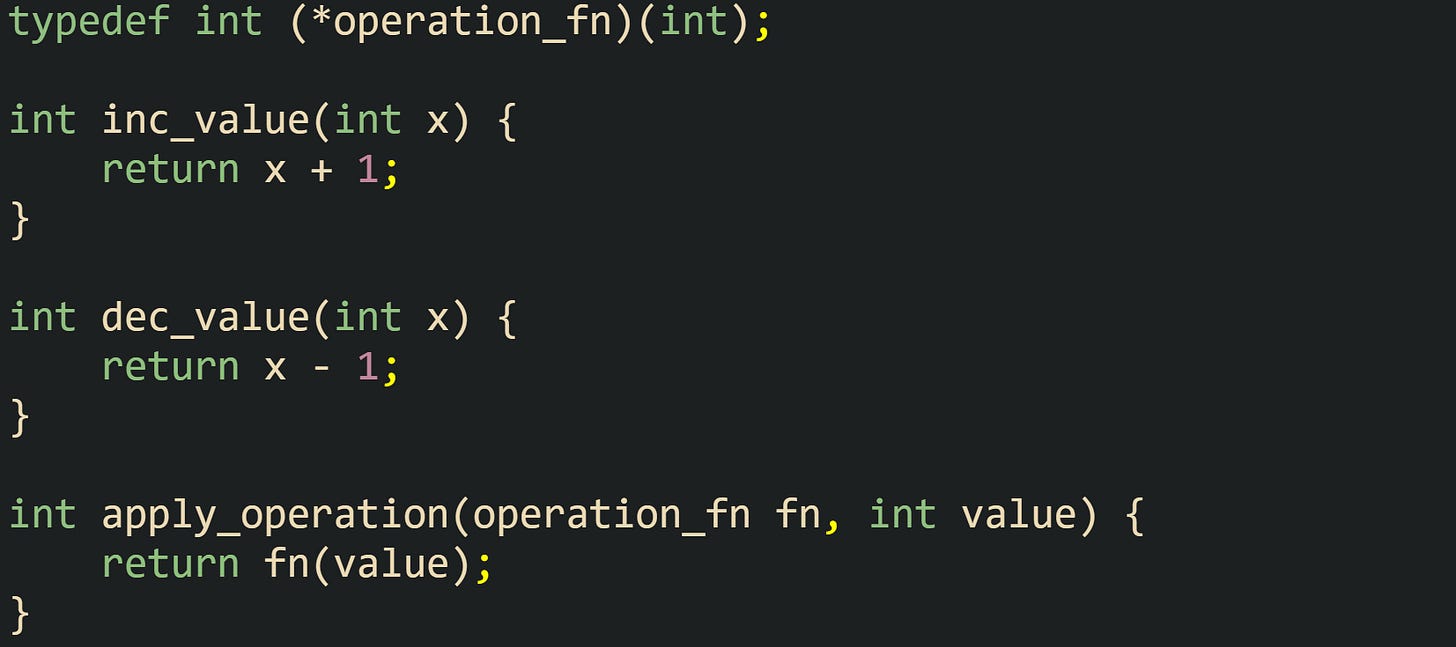

Take this simple arithmetic callback gives a first view:

The type int (*op)(int, int) means pointer to function that takes two int values and returns an int. Assigning multiply_ints to a variable of that type stores the address of the compiled code for multiply_ints. When apply_binary runs, it receives that address as a parameter, sets up the arguments according to the ABI for the platform, and then performs an indirect call through op. The result comes back in the ordinary return register, and apply_binary passes it along to its own caller.

Function pointers work equally well in tables that implement small dispatchers. A table of pointers to functions with matching signatures can represent a set of operations, and an index selects one of them at run time.

With this setup, client code can store addresses of inc_value and dec_value in variables or arrays of operation_fn and choose which function to call based on user input, configuration, or data values. The ABI does not change for indirect calls. Parameter values still travel in the same registers and stack locations, and return values still arrive in the same registers, so the only difference is that the call destination is fetched from memory or a register instead of being encoded as a fixed address in the instruction stream.

Function pointers also interact with library callbacks, where library code accepts a pointer to a user supplied function and then calls it when certain events occur. As long as both sides agree on the function type, the compiler can apply the same calling convention rules and type checks that ordinary function calls receive.

Conclusion

Function calls in C rest on a close link between the language rules visible in source code and the ABI rules that guide how compiled code runs. Arguments move through registers and stack slots into stack frames that also hold local data, while return values travel back in agreed registers or in memory buffers. Function pointers plug into the same calling rules so that indirect calls behave like direct ones from the machine’s point of view. With that model in mind, recursion, callbacks, and cross module calls all reduce to the same sequence of setting up a frame, transferring control, and bringing a result back.

![int sum_array(const int *values, int length) { int total = 0; int index = 0; while (index < length) { total += values[index]; index++; } return total; } int sum_array(const int *values, int length) { int total = 0; int index = 0; while (index < length) { total += values[index]; index++; } return total; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!K-T2!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1569717a-cdb3-419c-942f-cff29683b30f_1639x616.png)

Superb breakdown. The concept of C function calls existing simultaneously at language and ABI level is somethin I hadn't quite articulated before. I spent months debugging a callbackissue in embedded code and only later realized the callee was trashing registers the caller needed, making me wish I'd understood calling conventions this deeply back then. The hidden pointer mechanism for large struct returns is clever too.