Memory safety in Go relies on strict rules that control how memory is wiped before code reads from it. The language defines how every type starts at a well defined zero state, and the runtime allocator follows that contract for fresh allocations and for memory that gets recycled, so bytes from old values are not exposed to new ones. That behavior covers both stack variables and heap objects, from small integers to composite structs and slices, and keeps the starting state of new values predictable for all code that works with them.

Zero Values In Go Allocations

In Go, memory that back values always comes from somewhere inside the runtime allocator or from stack space the compiler arranged. New memory in Go does not appear with leftover bytes from earlier activity. Language rules say that any fresh variable or heap object begins in a zeroed state that matches its type, and allocator logic follows that rule whenever new storage is set up. That promise applies to global variables, locals on the stack, and heap allocations requested through helpers such as new and make, so code that reads a value for the first time always sees a predictable starting state.

Language Rules For Zero Values

Go defines a zero value for every type, and that rule lives at the language level, not just in the runtime implementation. Numeric types use 0, 0.0, or 0+0i, booleans use false, strings use "", and reference types such as slices, maps, channels, pointers, functions, and interfaces use nil. Composite types apply the same idea to their parts, so arrays contain zeroed elements and structs zero each field according to its type. Code that declares a variable without an explicit initializer still receives a fully defined value. A declaration such as var n int or var ready bool does not translate to literal assignments at the source level, yet the compiler arranges for the storage behind those variables to be zeroed before the first read. That behavior extends to package level variables, to locals in functions, and to fields inside composite types.

That output shows count and ready with valid values and prints a Session with every field zeroed, including a nil slice in Numbers. No assignment is needed to reach this state, because the language demands that every declared variable starts with the zero value for its type.

Zero values also appear when code uses composite literals that omit some fields or elements. Go allows writers to specify only the fields they care about, and any field left out receives its zero value automatically. Arrays and slices built from literals also fill unspecified elements with zeros.

That printout shows Limits.Hard as 0 and every entry in Flags as false. Composite literals do not escape the zero value rule, they just layer explicit initializations on top of a base where everything already starts at zero.

Stack allocated locals follow the same model. When a function declares a struct or array variable, Go treats that storage just like heap storage with regard to initialization. Compiler generated code may group several zeroing operations together into one block, or optimize away some zeroing when it proves that a variable always receives an explicit value before being read, yet safe Go code cannot observe bytes that were never initialized to a legal value for the type.

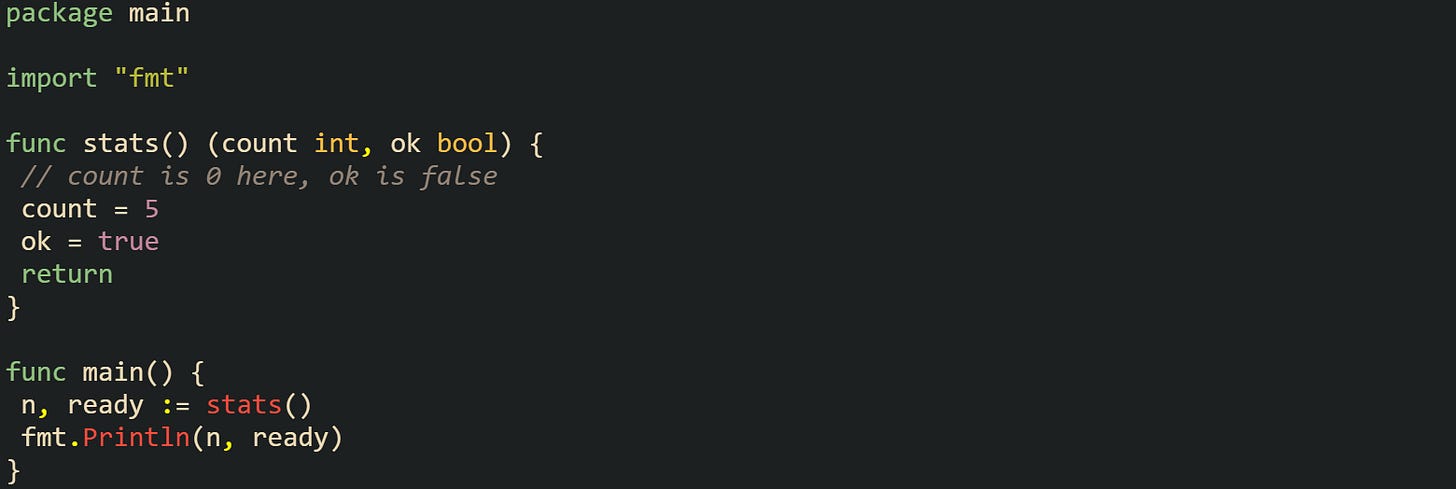

One more aspect of the language rule appears in function parameters and return values. Parameters are initialized with values passed from the caller, and return variables declared with named results start life at the zero value for their type, then receive assignments before the function returns. That means a function such as func stats() (count int, ok bool) begins with count equal to 0 and ok equal to false as soon as the call enters the function body, even before any line in the body executes.

That convention keeps function results consistent with the rest of the language and removes any special case where a named result would start in an undefined state.

Heap Allocation Behavior For Zeroing

Heap allocations rely on the runtime allocator to provide storage that already matches the zero value contract. Go organizes heap memory into arenas, then into pages, and then into spans that hold objects of a single size class. When new(T) or make for a slice, map, or channel leads to a heap allocation, allocator code picks a span for the right size and hands back a slot from that span.

Internally, allocator code centers on runtime.mallocgc. That helper receives the object size, type information, and flags that describe what kind of allocation is needed. One of those flags controls whether the new object must be zeroed before use. Allocator metadata on each span tracks if free slots are already known to hold zeros or if they still carry old data. When a span is marked as needing zeroing, mallocgc calls memclrNoHeapPointers to clear the object memory before the pointer goes back to Go code. At that stage the slot is not yet a live heap object from the collector’s point of view, so zeroing with memclrNoHeapPointers does not need pointer bookkeeping, and later writes that store real pointers run through the standard write barrier.

Objects that contain pointers always pass through zeroing on allocation. Pointer fields form the graph that the garbage collector traces, so any stale pointer bits left in a fresh object would confuse reachability analysis. Type information passed into mallocgc tells the runtime where pointer fields sit inside an object. That type information is recorded in heap metadata so the garbage collector can scan pointer fields later, while allocation-time zero-initialization happens before the object becomes type-safe. Functions such as typedmemclr and memclrHasPointers get used when zeroing memory that is already type-safe, and they can run write-barrier logic so the garbage collector sees pointer slots cleared when required. Objects with no pointer fields give the runtime some room to adjust zeroing strategies for performance, yet the language promise about observable behavior still holds. A type like struct{ A int64; B float64 } contains only numeric data, so the collector does not need those bytes for reachability. Allocator code can sometimes rely on the operating system to provide zero filled pages for fresh spans and can skip redundant writes when metadata already records that a span contains zeros in all free slots. From the point of view of Go code, a newly allocated value of such a type still reads as 0 for every field until user code writes something else.

Heap allocation helpers at the language level build on top of this machinery. Calling new(T) allocates storage for a single T, initializes it to the zero value through mallocgc and related helpers when it needs heap space, and returns a pointer. Escape analysis can let the compiler place that storage on the stack for short-lived values, but the initialized state seen by Go code stays the same. Calling make([]T, n) creates a slice backed by an array of length n that starts with every element set to the zero value for T, with placement again decided by escape analysis. Same helper logic sets up map and channel headers with zero values for their internal fields, though maps and channels manage their own internal storage further inside the runtime.

Those prints show a Job from new with every field zeroed, a queue slice where all three elements have zero values for each field, and a non nil map header that still holds no entries. Heap objects under those values carry zeros in their storage, and Go code reaches them only through pointers or headers that obey the same zeroing rules.

Heap allocation for composite literals also leans on the same zero value base. Literal syntax such as &Job{ID: 5} creates a Job value that starts with every field at its zero value and then stores 5 into the ID field, leaving Status and Values unchanged. Compiler generated code turns that pattern into a call to mallocgc plus a short series of stores when the value needs heap storage, or keeps it on the stack when escape analysis proves that safe, but in both cases the visible result matches a manual sequence of declarations and assignments. That combination of language level rules and allocator behavior gives heap values a predictable starting point. New objects from new, make, and composite literals always begin in a state that agrees with the zero value definition for their types, and allocator helpers such as mallocgc, memclrNoHeapPointers, and typedmemclr carry out the low level work needed to keep that contract intact.

Runtime Memory Reuse Behavior

Garbage collection in Go does more than free memory. It also prepares that memory so later allocations do not observe leftover bytes from earlier values. The collector traces which objects are still reachable, marks those objects, and then sweeps through allocation spans that hold heap slots. Any slot that no longer belongs to a live object returns to a free list that the allocator can draw from, but allocator code and collector code cooperate so those slots either already contain zeros or will be wiped before they are handed to new values. This is true for the standard concurrent mark-sweep collector and for the experimental Green Tea collector when it’s enabled with GOEXPERIMENT=greenteagc.

Span Free Lists With needzero Flag

Each span belongs to a size class, and every slot inside that span has the same size, which lets the allocator hand out memory quickly without asking the operating system every time. When sweeping finishes with a span, it has a mix of live and dead objects. Dead objects are turned back into free slots and are placed on a free list or represented as a range of indexes. The span also carries a flag named needzero that records whether free slots in that span still require zeroing before reuse. Allocator code that serves new heap allocations checks this flag and a local needzero decision before calling memclrNoHeapPointers to wipe memory for a returning slot. If free slots are already zeroed, the allocator skips that work.

Sweep has some flexibility about where the actual zeroing happens. One option is to overwrite memory for dead slots during the sweep phase. If sweep writes zeros into all freed objects, then the span can reset needzero to false, and future allocations from that span do not need extra wiping. One option is to leave freed slots untouched during sweep and keep needzero true. Allocator code later sees that the slot comes from a span that still needs zeroing and calls memclrNoHeapPointers on that region before publishing a pointer back to Go code. Both choices lead to the same outcome for allocations, but they trade work between background sweeping and on demand allocation. Green Tea keeps this basic contract but changes the way marking steps through spans, focusing more on spatial locality by visiting objects in nearby memory blocks instead of jumping through pointer chains across the heap. That change affects cache use and collector throughput but does not relax the guarantees about zeroing and safe reuse.

User code cannot see the needzero flag directly, yet the effect shows up in how allocations behave when many short lived objects appear. A loop that builds and discards structures will cause spans to fill, be swept, and then be reused. Even if the same span slot is used first for a User object and later for a Job object, the second allocation will see zeros before any field writes run. That means no string data, IDs, or other bytes from the earlier User value leak into the Job that replaces it in that slot. The allocator accomplishes this either by having sweep set every freed byte to zero ahead of time or by calling memclrNoHeapPointers on the exact region for the new object when allocating from a span that still carries needzero.

This short example helps connect this process visually:

The Record created at the end arrives with ID set to 0 and every byte in Data set to zero. Nothing in the language or runtime gives a path for earlier Data contents from makeAndDrop to reappear in a fresh Record, even though allocation likely reuses spans and perhaps the same slot.

Sensitive workloads add one more wrinkle. runtime/secret is an experimental package that only exists when building with GOEXPERIMENT=runtimesecret. secret.Do wipes registers and stack space used by the call tree before returning, and it tracks heap allocations made inside the call so the runtime can erase that heap memory after it becomes unreachable.

Compiler Driven Zeroing For Slices

Slices bring another angle to memory reuse. A slice header is a small value with a pointer, a length, and a capacity. That header can point at existing arrays on the stack or heap, or it can point at new backing arrays that make allocates. Every time a new backing array arrives from make, that array goes through the same span allocation path as any other heap object and comes out fully zeroed. The compiler sometimes needs to request extra zeroing when growing slices or resetting them, and that work also runs through runtime helpers such as memclrNoHeapPointers and friends.

Let’s consider a helper that grows a slice to a specific length and keeps any existing prefix:

When the make([]byte, n) path runs, the new backing array starts with zeros, so bytes past the copied prefix are already 0. When the early return path runs and buf[:n] re-slices the existing backing array, bytes past len(buf) keep whatever values already lived in that array.

Slice zeroing matters even more when code wants to reuse a buffer across operations. Built-in clear works on slices and maps, setting slice elements to zero values and removing all entries from maps. For slices with non pointer elements, the compiler commonly chooses memclrNoHeapPointers as the helper, which zeroes a range of bytes while skipping pointer bookkeeping. For slices that hold pointers, the compiler emits calls into helpers that understand pointer layouts, such as typedmemclr or memclrHasPointers, so the garbage collector sees that references disappeared from those positions.

That behavior surfaces in pool based buffer reuse.

This pool keeps one backing array inside bufPool. Each call to useBuffer writes over every element, so no old contents survive. The resetAndUseAgain function loops through the slice and writes zeros by hand, but clear on the slice would have the same effect while going through the runtime helpers that know how to treat that memory for garbage collection. Memory for the backing array moves between active code and the pool, yet every reuse runs through writes that prepare the bytes for the next user.

Slices that store pointers call for a different pattern. When a slice holds pointers to objects and code wants those objects to become collectible, zeroing the slice elements matters for more than safety on reuse. It also removes references that keep heap objects alive.

After the loop that sets every element to nil, there are no references left in the slice to keep those Node instances alive. During the next garbage collection, the collector can reclaim those heap objects and eventually reuse their spans. When a new allocation later receives a slot from those spans, span metadata and helpers such as memclrHasPointers guarantee that previous Node pointers will not show up in fresh values.

Conclusion

Go ties language rules about zero values, allocator behavior, and garbage collection into one continuous process that keeps new and recycled memory in a defined state. New variables and heap objects start from type specific zero values, while spans on the heap move through marking, sweeping, needzero flags, and helpers such as mallocgc, memclrNoHeapPointers, and typedmemclr so reused slots are wiped before code can see them. Slice operations, stack handling, and features such as secret.Do apply the same ideas to buffers, stack frames, and short lived secrets, so memory that previously held data for one value is either unreachable or has been overwritten before it is presented as a fresh value again. Those mechanics give Go memory behavior where every observable value either reflects zero initialization or explicit writes, not leftover bytes from unrelated objects.

![package main import "fmt" type Session struct { ID int Active bool Label string Numbers []int } func main() { var count int var ready bool var s Session fmt.Println(count) // 0 fmt.Println(ready) // false fmt.Printf("%#v\n", s) } package main import "fmt" type Session struct { ID int Active bool Label string Numbers []int } func main() { var count int var ready bool var s Session fmt.Println(count) // 0 fmt.Println(ready) // false fmt.Printf("%#v\n", s) }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!rQhy!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Faae8ad4b-526a-403c-9fe5-dff963aa6d93_1551x699.png)

![package main import "fmt" type Limits struct { Soft int Hard int } type Config struct { Name string Limits Limits Flags [3]bool } func main() { cfg := Config{ Name: "worker", Limits: Limits{ Soft: 10, // Hard left out on purpose }, // Flags left out } fmt.Printf("%#v\n", cfg) } package main import "fmt" type Limits struct { Soft int Hard int } type Config struct { Name string Limits Limits Flags [3]bool } func main() { cfg := Config{ Name: "worker", Limits: Limits{ Soft: 10, // Hard left out on purpose }, // Flags left out } fmt.Printf("%#v\n", cfg) }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!2hjD!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F26a4d1b8-02e4-46ad-8210-33f062915c31_1636x754.png)

![package main import "fmt" type Job struct { ID int Status string Values []float64 } func main() { p := new(Job) queue := make([]Job, 3) cache := make(map[int]*Job) fmt.Printf("%#v\n", *p) fmt.Printf("%#v\n", queue) fmt.Println(cache == nil) } package main import "fmt" type Job struct { ID int Status string Values []float64 } func main() { p := new(Job) queue := make([]Job, 3) cache := make(map[int]*Job) fmt.Printf("%#v\n", *p) fmt.Printf("%#v\n", queue) fmt.Println(cache == nil) }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!CBb4!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbc34c1cc-6520-4109-b6e3-b8593a4b652b_1553x664.png)

![package main import "fmt" type Record struct { ID int Data [16]byte } func makeAndDrop(n int) { for i := 0; i < n; i++ { r := &Record{ID: i} _ = r } } func main() { makeAndDrop(1_000_000) r2 := &Record{} fmt.Printf("%#v\n", r2) } package main import "fmt" type Record struct { ID int Data [16]byte } func makeAndDrop(n int) { for i := 0; i < n; i++ { r := &Record{ID: i} _ = r } } func main() { makeAndDrop(1_000_000) r2 := &Record{} fmt.Printf("%#v\n", r2) }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!dICA!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F008431e4-04bc-459f-b918-ddcc574fb60f_1554x768.png)

![package main import "fmt" func grow(buf []byte, n int) []byte { if cap(buf) >= n { return buf[:n] } next := make([]byte, n) copy(next, buf) return next } func main() { b := []byte{1, 2, 3} b = grow(b, 8) fmt.Println(b) } package main import "fmt" func grow(buf []byte, n int) []byte { if cap(buf) >= n { return buf[:n] } next := make([]byte, n) copy(next, buf) return next } func main() { b := []byte{1, 2, 3} b = grow(b, 8) fmt.Println(b) }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!EBgK!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F915e00f3-0665-43f8-8cdc-fca274c43bbb_1558x629.png)

![package main import ( "fmt" "sync" ) var bufPool = sync.Pool{ New: func() any { b := make([]byte, 16) return &b }, } func useBuffer(id int) { bp := bufPool.Get().(*[]byte) b := *bp for i := range b { b[i] = byte(id) } fmt.Println("buffer", id, b) *bp = b bufPool.Put(bp) } func resetAndUseAgain() { bp := bufPool.Get().(*[]byte) b := *bp for i := range b { b[i] = 0 } fmt.Println("reset buffer", b) bufPool.Put(bp) } func main() { useBuffer(1) useBuffer(2) resetAndUseAgain() } package main import ( "fmt" "sync" ) var bufPool = sync.Pool{ New: func() any { b := make([]byte, 16) return &b }, } func useBuffer(id int) { bp := bufPool.Get().(*[]byte) b := *bp for i := range b { b[i] = byte(id) } fmt.Println("buffer", id, b) *bp = b bufPool.Put(bp) } func resetAndUseAgain() { bp := bufPool.Get().(*[]byte) b := *bp for i := range b { b[i] = 0 } fmt.Println("reset buffer", b) bufPool.Put(bp) } func main() { useBuffer(1) useBuffer(2) resetAndUseAgain() }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!-16V!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F142a3d09-e8b0-4ef9-b727-777525e6149c_1456x908.png)

![package main import ( "fmt" "runtime" ) type Node struct { Value int Next *Node } func main() { nodes := make([]*Node, 3) for i := 0; i < 3; i++ { nodes[i] = &Node{Value: i} } fmt.Println("before reset", nodes[0]) for i := range nodes { nodes[i] = nil } runtime.GC() fmt.Println("after reset", nodes[0]) } package main import ( "fmt" "runtime" ) type Node struct { Value int Next *Node } func main() { nodes := make([]*Node, 3) for i := 0; i < 3; i++ { nodes[i] = &Node{Value: i} } fmt.Println("before reset", nodes[0]) for i := range nodes { nodes[i] = nil } runtime.GC() fmt.Println("after reset", nodes[0]) }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_nuM!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6b9bd34b-b474-44b0-9bfd-11c42724378b_1652x756.png)

Really solid breakdown of the zeroing guarantees across the entire allocation lifecycle. The needzero flag detail is particularly useful sinec most devs never look at span metadata, and knowing that sweep can defer zeroing to allocation time explains why some profiling shows those memclr calls spiking unexpectedly. I ran into this exact behavior optimizing a buffer-heavy service where we assumed zero-init was "free" until allocator traces showed otherwise, switching to careful buffer reuse cut those costs way down.