Go handles large numbers of connections by leaning on its runtime. Beneath the surface of goroutines and channels runs a system that talks directly with the operating system’s event notification features. At the center is the netpoller, which parks goroutines when I/O would block and resumes them when the OS reports readiness or completion for the I/O handle. That coordination between Go’s runtime and system calls like epoll, kqueue, or IOCP is what lets Go scale smoothly when networks get busy.

Type Parameters in Go

Generics in Go arrived with version 1.18, after years of debate and design work. The goal was to let developers write functions and data structures that work across different types without giving up type safety or runtime speed. Instead of relying on reflection, the compiler does the heavy lifting by creating specialized versions of functions and types based on type parameters. This makes generic code feel natural to use while still producing efficient machine code.

Compile Time Specialization

Type parameters are placeholders that let you describe what kind of values a function or type should work with. During compilation, Go substitutes real types and generates stenciled code based on each type’s GC shape, and when a constraint needs it, passes small dictionaries for operations like comparisons or method calls. In many cases the result performs like hand-written code, but some cases carry a little overhead. That’s an important distinction from reflection, which often carries runtime cost.

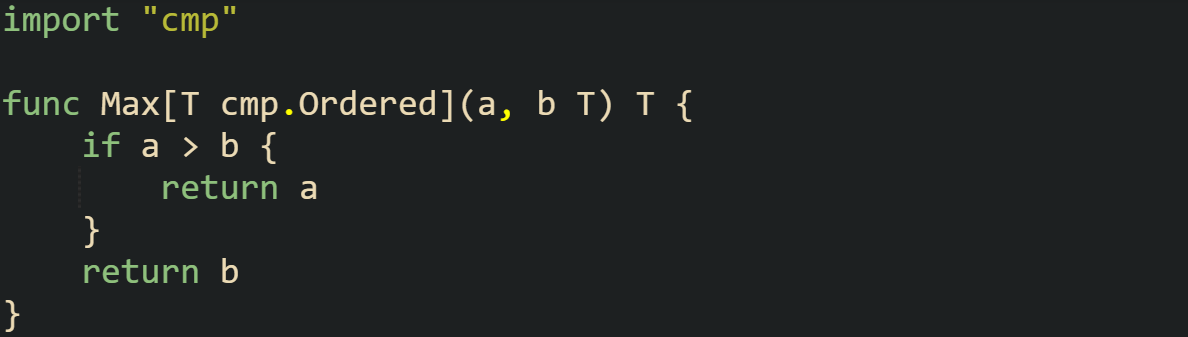

Take a sorting helper as an example:

Calling Max(5, 9) generates a version where T is int. Calling Max("blue", "red") generates another version where T is string. Both are compiled separately. You write one function, but the compiler turns it into two highly specific functions in the background.

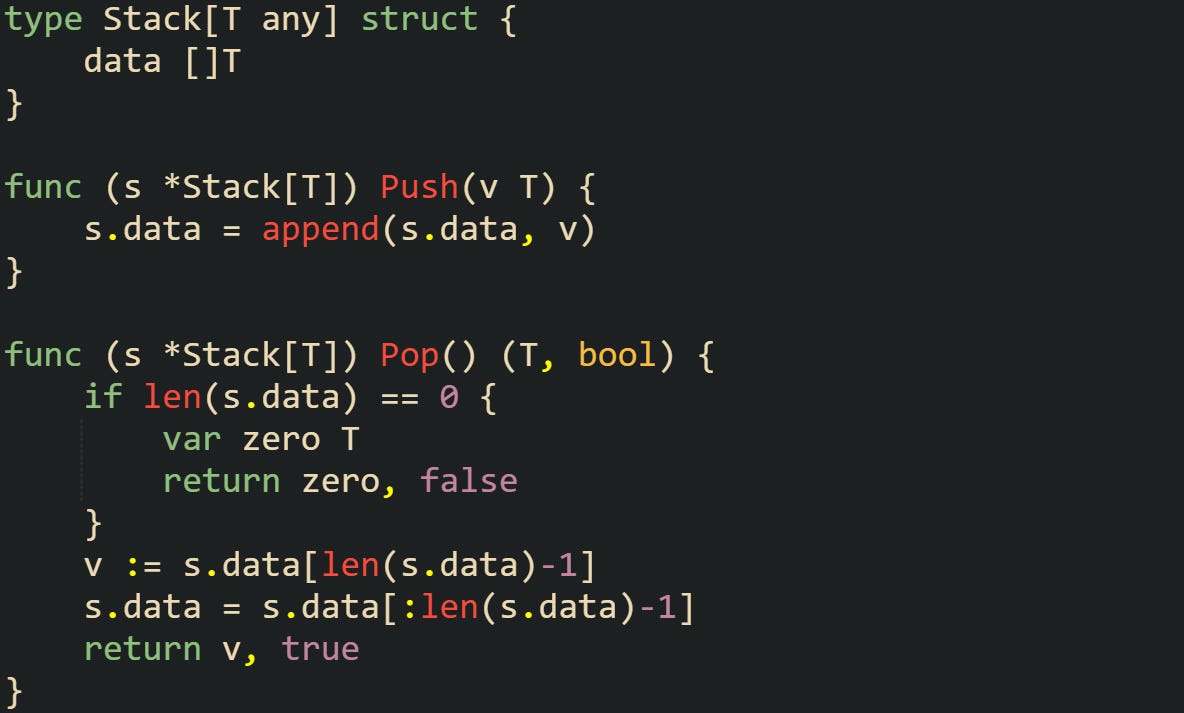

This behavior isn’t limited to standalone functions. Generics also apply to user-defined types. Imagine building a stack structure:

Creating Stack[int] or Stack[string] gives you two distinct stacks at runtime, both type-safe and both compiled to direct machine code. There’s no reflection involved, and when work is done directly on T there’s no interface conversion, so performance stays predictable.

Generics with Interface Constraints

Specialization only works properly if the compiler can reason about what operations are valid on a type. That’s where constraints come in. A constraint describes what a type parameter is allowed to do. The simplest constraint is any, meaning “accept everything.” More interesting constraints define specific operations that must be supported.

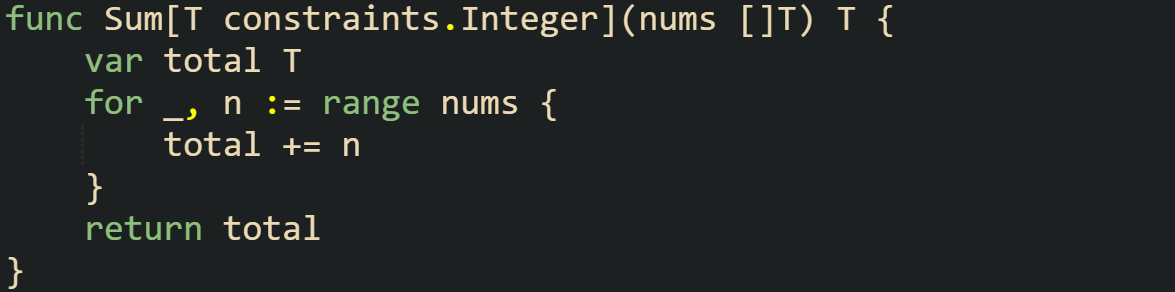

This function only compiles when T is some integer type like int or int64. If you try to pass []float64, the compiler refuses because float64 doesn’t satisfy the constraints.Integer contract. That guarantee means you don’t need runtime checks.

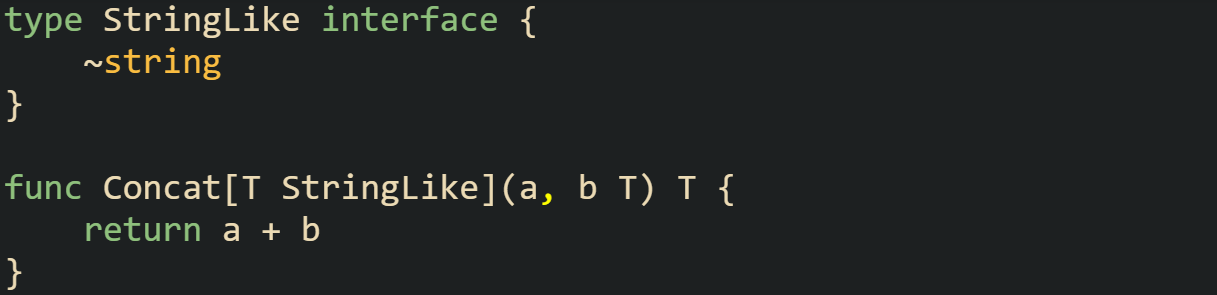

Constraints can also describe structural requirements. Go supports approximation through the tilde operator, which says “accept types that behave like this base type.” For example:

Even a user-defined type with string as its underlying type works with Concat. That gives flexibility without dropping type safety.

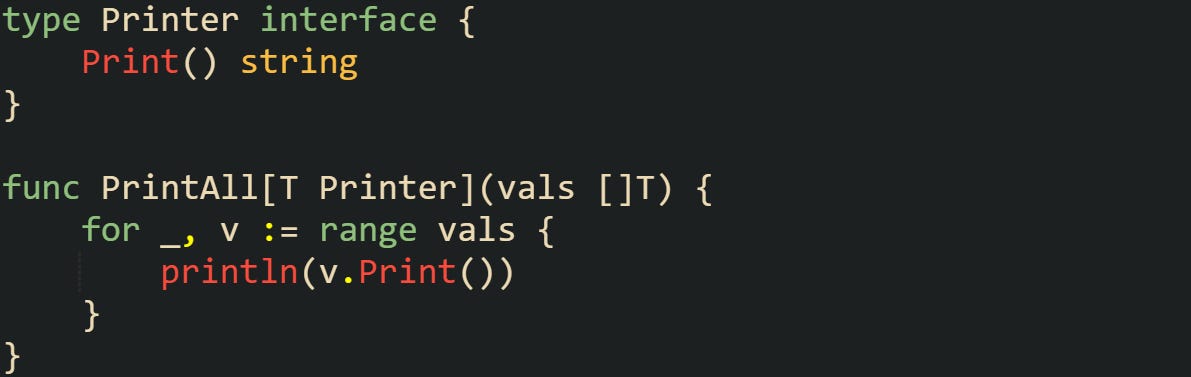

Some constraints involve multiple methods, effectively allowing generic code to depend on interfaces. Imagine a simple printer interface:

Any type that implements Print can be passed to PrintAll, and the compiler generates code that calls Print directly on each element. No runtime reflection, no guesswork.

These mechanisms make generics expressive while keeping the safety and efficiency developers expect in Go.

Go Runtime Network Poller

Goroutines feel light enough to create by the thousands, but the reason that scales well has everything to do with how Go ties itself into the operating system. The runtime doesn’t block threads on I/O. Instead, it hands that work to a netpoller that listens to file descriptors and wakes goroutines only when something is ready. That design keeps threads free for work and makes it practical to juggle so many concurrent connections.

The Netpoller Abstraction

The netpoller is an internal layer inside the Go runtime that decides when a goroutine can safely resume after calling a blocking operation. Its job is to connect the world of goroutines with the I/O readiness notifications offered by the host system. When a goroutine makes a system call like Read, the runtime checks if data is already buffered. If not, the goroutine is parked and its interest in that file descriptor is registered with the netpoller. The poller itself runs in a loop, waiting for the operating system to report readiness.

You can see how this affects code indirectly with a simple echo server.

Each Read here might block in a traditional threaded model, but in Go the goroutine is paused while the netpoller watches that socket. When the kernel says more data is available, the goroutine is placed back on a run queue.

Integration with epoll, kqueue, and IOCP

Different operating systems provide different event mechanisms, so Go adapts itself to the environment it’s compiled on. Linux gives the runtime epoll, macOS and BSD offer kqueue, while Windows relies on IOCP. Each of these interfaces reports readiness for many file descriptors at once, making them ideal for scaling servers.

On Linux, epoll_wait is called by the poller thread to block until one or more file descriptors have something to report. When a connection becomes ready, epoll passes back an event structure. The runtime then marks the goroutine waiting on that descriptor as runnable. That goroutine is placed into the scheduler’s run queue so it can be picked up by any available thread. This handoff means threads don’t sit idle while waiting on I/O, and the system can keep serving new work without being tied up by stalled connections.

Kqueue operates similarly but has its own event filter model. A call to kevent blocks until a registered event, like readability or writability, fires. Go abstracts that difference so that goroutines don’t care what operating system they run on.

Windows handles things differently through IO Completion Ports. Instead of readiness, IOCP reports completion of overlapped operations. The Go runtime has to integrate with this model carefully, making sure overlapped I/O requests map correctly to goroutines waiting on sockets.

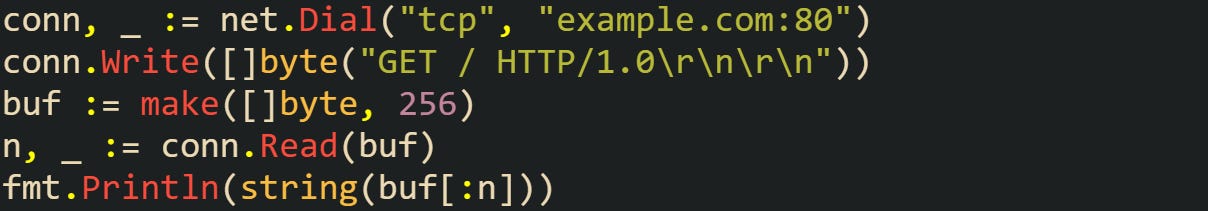

A quick example shows how portable this feels to the developer even while the runtime adapts under the surface:

That short snippet triggers epoll on Linux, kqueue on macOS, and IOCP on Windows without a single code change on the developer’s part.

How Goroutines Sleep and Wake

Parking and waking goroutines is the next piece of the puzzle. When a goroutine calls into a network operation and data isn’t ready, the runtime records which file descriptor it’s interested in and removes it from the active run queue. The scheduler treats it as asleep. The poller waits in a blocking system call like epoll_wait. After the kernel says the descriptor is ready, the runtime moves the goroutine back into the run queue. No spinning or busy waiting is involved.

To picture this in practice, think about a server handling thousands of connections where most clients send data sporadically. Without the netpoller, threads would be stuck waiting, wasting resources. With the poller, the cost of having idle connections is minimal, because goroutines representing them are simply parked.

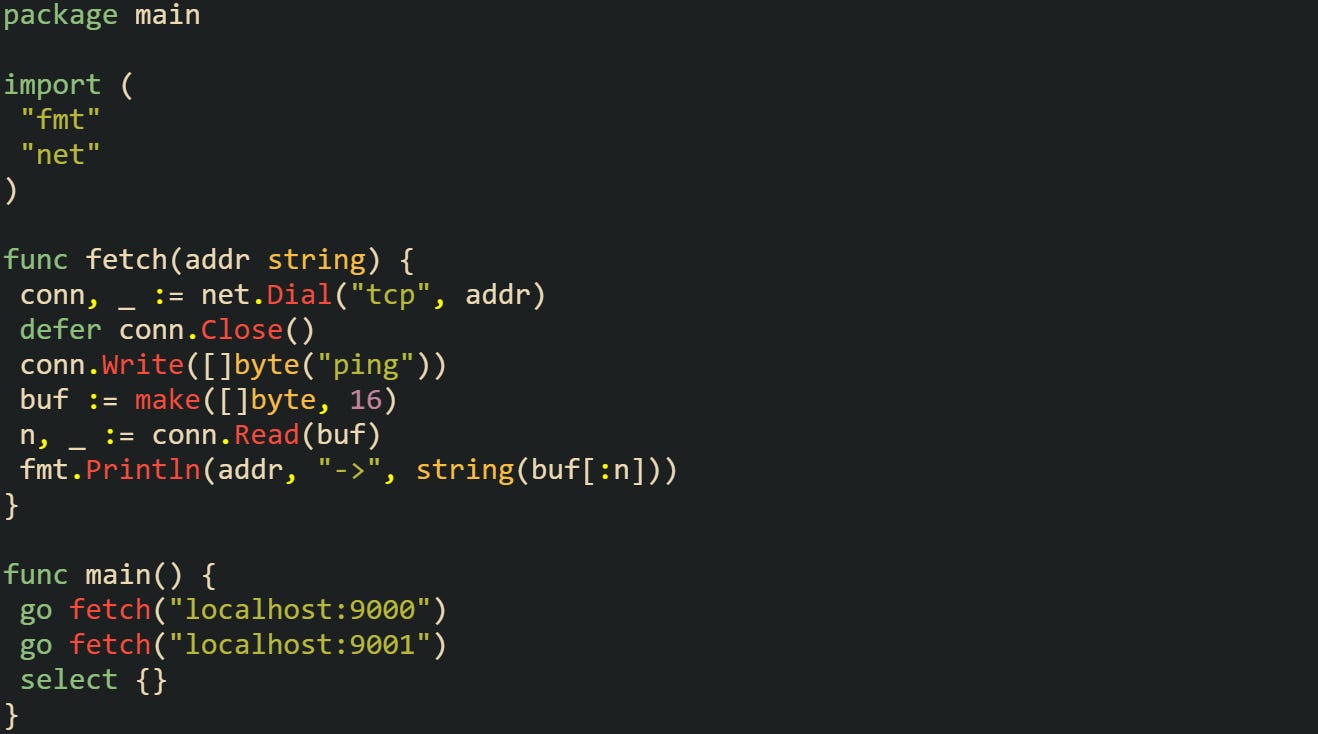

Here’s a short client snippet that relies on this behavior while talking to multiple servers in sequence:

Both goroutines can block on reads, yet no thread is tied up waiting. The poller coordinates with the kernel to wake them independently when each reply arrives.

Poller and Scheduler Cooperation

The Go scheduler doesn’t operate in isolation from the netpoller. They share information to make sure runnable goroutines don’t get stuck waiting longer than they should.

The scheduler’s model is built on M (machine, or thread), P (processor context), and G (goroutine). When the scheduler runs out of goroutines to execute, it calls into the poller to see if any descriptors are ready. If events have arrived, those goroutines are immediately injected into the run queues so threads can pick them up. This tight loop between scheduler and poller keeps latency low. Goroutines that are ready to proceed aren’t left waiting for long scheduler cycles, because the poller wakes the scheduler promptly.

The runtime also takes care to balance how much time is spent checking the poller versus running goroutines. That balance avoids starving goroutines that are CPU-bound while still serving I/O-bound ones quickly.

Runtime Interaction

A more complete look can be taken with a small concurrent chat server.

Every call to Read on the connection relies on the netpoller. Goroutines that don’t yet have incoming data are paused, freeing up threads to handle other connections. When a line arrives, the kernel signals readiness, the poller marks the goroutine as runnable, and the scheduler hands it a thread to continue. To the developer, it feels like straightforward socket reads and writes, but the runtime is coordinating across thousands of descriptors in the background.

Conclusion

Go brings two important mechanics together. Type parameters let the compiler generate stenciled code and, when constraints require it, pass small dictionaries, while the netpoller links goroutines to the operating system’s event system so threads aren’t tied up on I/O. That combination lets Go scale network workloads smoothly while keeping code approachable for the developer.