Gradle builds for large Spring Boot projects can grow from a few seconds to several minutes as modules, tests, and plugins accumulate. Gradle 9.0 changes that balance by treating the configuration cache as the preferred execution mode while still keeping the familiar build cache, parallel execution, and the usual dependency management model in place. For Spring Boot 3 and 4, the official Gradle plugin supports Gradle 9 and works with the configuration cache, so these features are safe to rely on for projects that run on Java 17 through 25.

Gradle Build Behavior in Large Spring Boot Projects

The Gradle build process follows a regular sequence, and large Spring Boot projects put that structure under stress. A small demo app barely touches the limits of the tool, while a multi module service platform with hundreds of thousands of lines of code forces Gradle to evaluate many build scripts, apply many plugins, and coordinate a wide set of actions before a single class file is produced. To tune performance later, it helps to know where that time goes and how Gradle 9 changes the balance between configuration work and execution work for these projects.

Gradle Build Lifecycle in Large Projects

Every Gradle build run follows the same high level flow, even when the command line only shows a short message and a summary at the end. The initialization phase decides which projects belong to the build. The configuration phase reads the build scripts for those projects, applies plugins, creates the build actions, and builds the execution graph. The execution phase runs those actions, such as Java compilation, test execution, packaging, code quality checks, and publishing. In a small codebase this flow finishes quickly, so configuration time barely registers. In a large Spring Boot project, the configuration phase can take a noticeable share of the total time, because Gradle has to touch many separate project directories and scripts before the main work can even start.

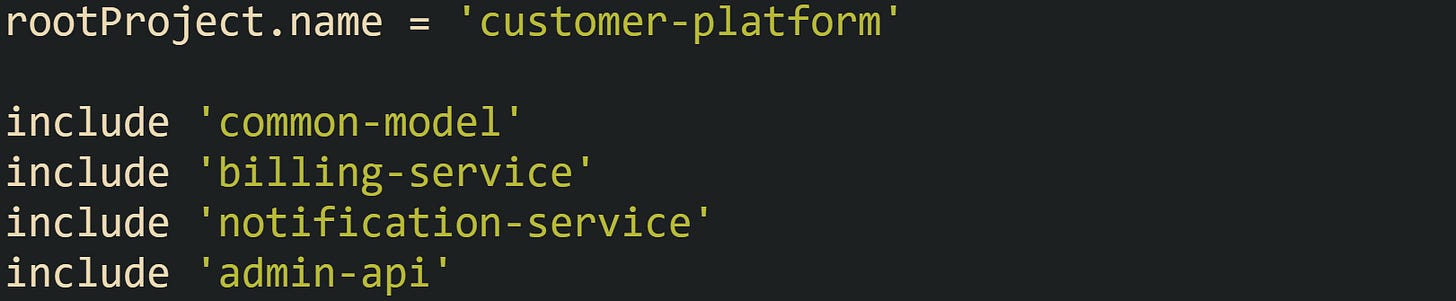

Typical multi project Spring Boot builds connect modules through the settings.gradle file in the root directory. That file tells Gradle which subprojects exist, which is the main assembly project, and sometimes how project names map to directory names. Initialization reads this file before configuration begins, so any change here can affect the entire build structure.

Take this example of a multi project settings file:

Gradle now knows it has four subprojects plus the root project. During the configuration phase it will read build.gradle for common-model, billing-service, notification-service, admin-api, and the root project, apply the declared plugins, and register all the build actions that those scripts define.

Each Spring Boot module usually applies the Java plugin and the Spring Boot Gradle plugin, and often the dependency management plugin as well. These plugins add many build actions to the project, such as Java compilation, test execution, bootJar, and configuration processing. When dozens of modules share this pattern, the number of actions grows, and Gradle must configure all of them before the execution phase can start.

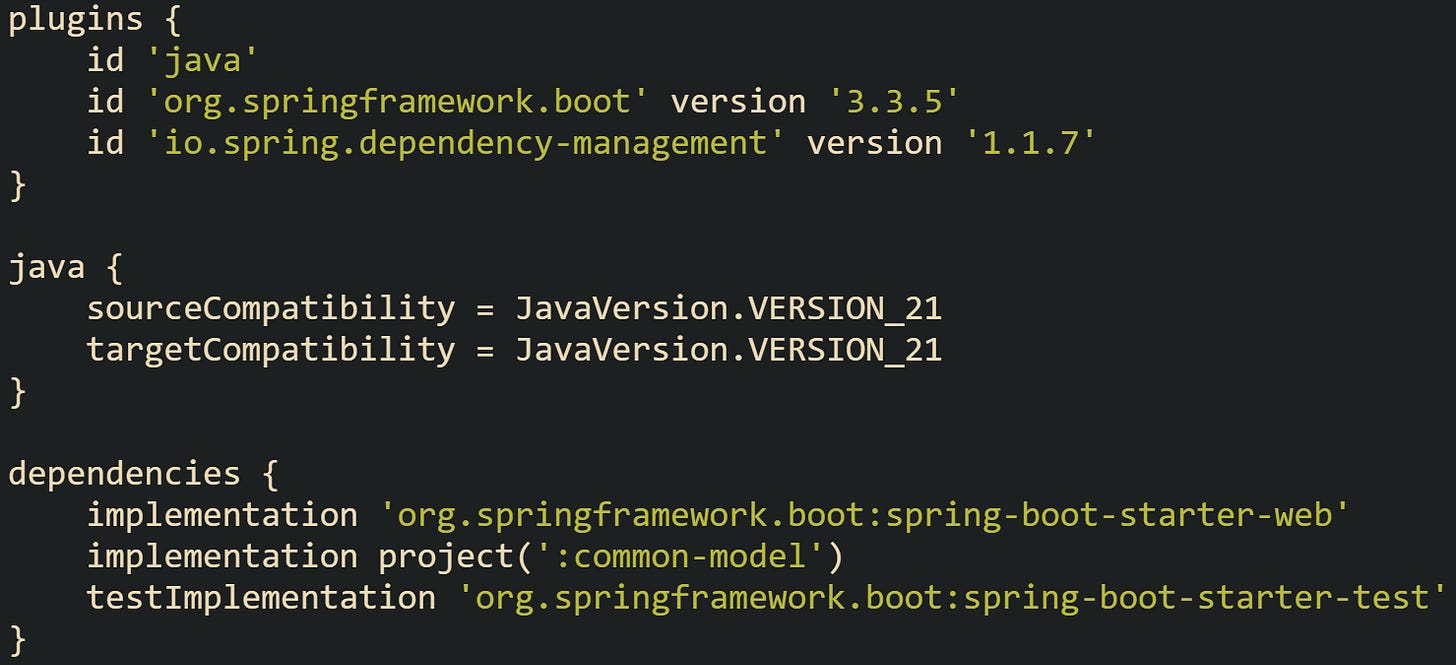

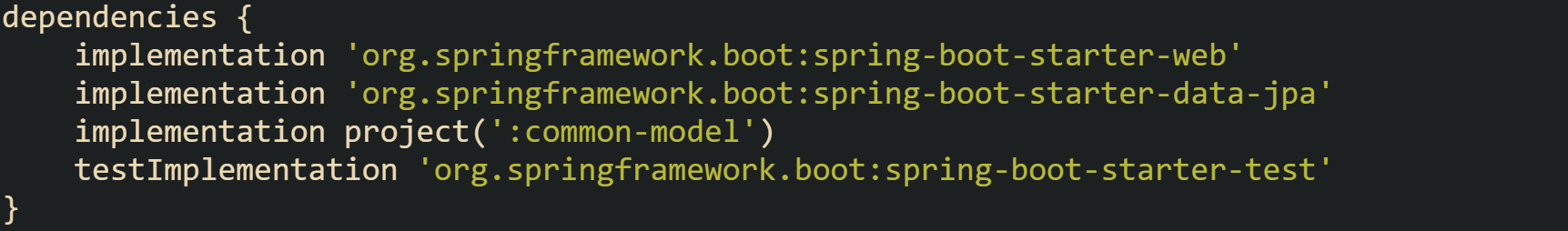

This Spring Boot module build script reflects that structure:

The plugin section creates the main build actions for this module, while the dependencies section affects which jars Gradle resolves for the compile and test classpaths. When similar scripts exist across many modules, configuration time grows because Gradle must execute these build scripts, talk to the plugin code, and build the internal model for each project.

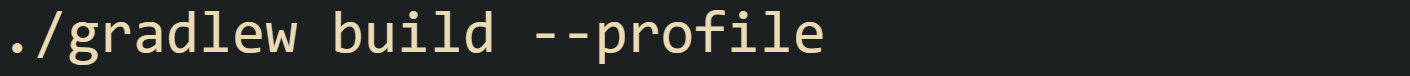

Developers sometimes want to see how much time configuration consumes compared to execution. Gradle has a profiling mode that produces an HTML report with separate timing for configuration and execution. Running a build with profiling turned on gives solid numbers for a given project layout and hardware.

This Gradle command runs a build with profiling turned on:

The generated report lists the configuration time for each project and the execution time for the main build actions. Long configuration times often point to heavy plugin use, complex build logic in buildSrc or included builds, or a situation where many build scripts run even when the requested tasks touch only a small part of the project tree.

Spring Boot projects also tend to have richer testing layouts than small libraries. There may be separate source sets for unit tests, integration tests, and contract tests, or even separate Gradle modules dedicated to different layers of testing. Every extra source set and module adds configuration load and creates more actions in the execution phase. When a shared module changes, that update can trigger extra compilation work and extra test work in many dependents. Gradle’s caching and parallel execution features exist to reduce this repeated work, but they still depend on the lifecycle described here, with a heavy configuration step followed by a dense execution step.

Effects of Gradle 9 on Spring Boot Builds

Gradle 9.0 introduces a major change in how configuration time is handled. Earlier Gradle versions treated the configuration cache as a more experimental feature that needed special flags and careful review. With Gradle 9, configuration cache is treated as the preferred execution mode, but it is still opt in for existing builds. New projects created with gradle init have it enabled by default, while existing builds still need to turn it on explicitly through org.gradle.configuration-cache=true in gradle.properties or by passing --configuration-cache on the command line. The idea is that after Gradle finishes configuration for a given set of requested build actions, it can serialize that configuration state, store it on disk, and reload it later instead of running all the configuration logic again.

Spring Boot’s Gradle plugin has kept pace with these changes and now supports Gradle 9, including configuration cache. That means a modern Spring Boot 3 or 4 project can take full advantage of configuration cache without rewriting the entire build. The main limits show up when third party plugins or custom build logic do things that configuration cache does not allow, such as starting external processes or reading environment variables in ways Gradle cannot track as inputs. Those cases need adjustments so Gradle can record all the necessary information and reload it safely.

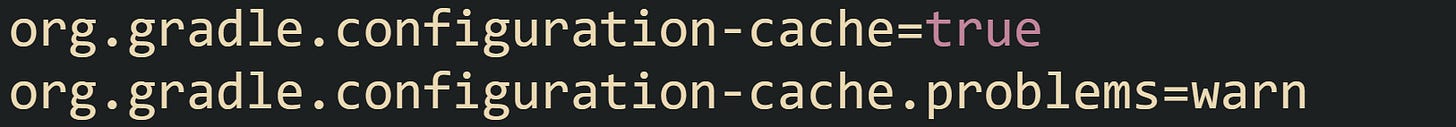

A simple Gradle 9 gradle.properties file in the root project can turn configuration cache on and give Gradle permission to log problems as warnings during a migration period.

This gradle.properties snippet turns configuration cache on for Gradle 9 builds:

This configuration tells Gradle to record configuration state and reuse it on later runs, while still reporting any features that do not work with configuration cache yet. Large Spring Boot builds benefit most when developers repeat the same frequent commands, such as build, test, or bootJar, many times during a day, because configuration cache avoids full configuration on these repeated runs when inputs have not changed.

Gradle 9 still relies on the build cache to reduce execution time, and it pairs well with configuration cache by shortening work in the execution phase while configuration cache shortens work in the configuration phase.

Parallel execution remains available in Gradle 9, particularly helpful for multi project Spring Boot builds where many modules do not depend on each other. When developers add the --parallel flag or set org.gradle.parallel=true in gradle.properties, Gradle can run build actions from independent projects at the same time on machines with several cores. Configuration cache and build cache still apply in that mode, so large builds often gain from a mix of all three features.

Gradle 9 also requires a modern Java runtime. The tool itself runs on Java 17 through Java 25, which lines up with the Java range Spring Boot 3 and 4 expect for application code. Keeping Gradle and Spring Boot on the same JDK version cuts down on subtle compatibility issues, allows modern language features in both build logic and application code, and removes the need for separate JDK installations just to run the build.

Practical Gradle Optimizations for Large Spring Boot Projects

Large Spring Boot builds spend time in very predictable places. Some of that time goes into configuring many projects, some goes into compiling and testing code that has not really changed, and some goes into resolving wide dependency graphs. Gradle 9 gives several tools that help with each of these pressure points. Build cache cuts down repeat work in the execution phase, configuration cache cuts down repeat work in the configuration phase, parallel execution spreads independent build actions across CPU cores, and dependency trimming keeps classpaths from growing without control. When these features are set up with care, large multi module projects start to behave much more politely during day to day development as well as in CI.

Build Cache Configuration for Spring Boot Modules

Build cache centers on reuse. Gradle looks at the declared inputs for a build action, such as source files, compiler arguments, classpath entries, and some environment details. If those inputs match a previous run, Gradle can restore outputs from cache instead of running the same action again. Local cache keeps those outputs on the same machine, while a remote cache lets many machines share them.

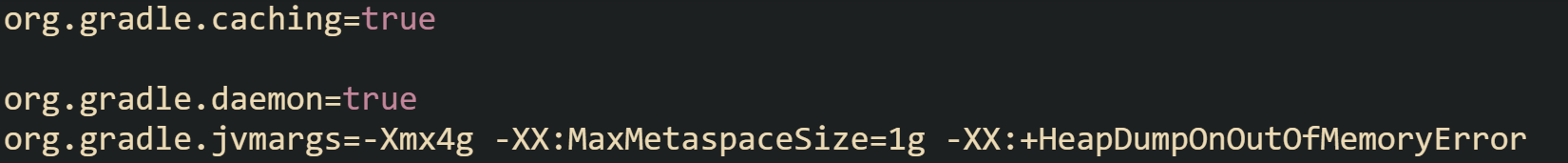

Most Spring Boot projects start with local cache. At the root of the build, a gradle.properties file usually carries that switch, because properties there apply across all modules.

One common gradle.properties layout that turns on caching and keeps the Gradle daemon ready for reuse looks like this:

That configuration line for org.gradle.caching activates Gradle’s normal build cache behavior. The daemon and JVM settings give Gradle enough memory space for multi module builds and keep process startup overhead from repeating more than needed during a busy day of edits and builds. Local cache entries live inside the Gradle user home and Gradle manages eviction and reuse there.

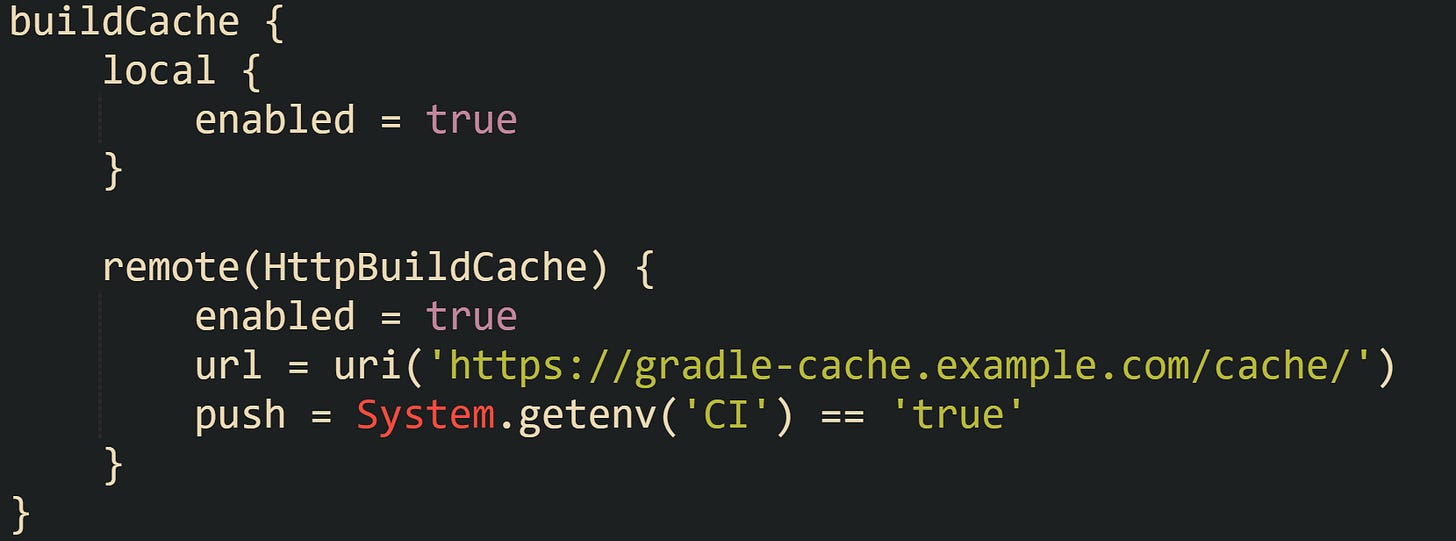

Shared codebases with many developers or a strong CI presence usually see greater benefit when a remote cache enters the picture. Remote cache lets one machine pay the cost for a heavy build action and then many other machines reuse that output. Gradle supports an HTTP based remote cache, configured in the root level settings.gradle.

That same settings.gradle file can combine local cache with a basic HTTP remote cache:

This arrangement keeps the local cache in place while also pointing Gradle at a shared cache node. CI builds push entries so that a main pipeline can populate the cache with outputs from full builds on main branches. Developer machines then draw from both local and remote caches, which takes pressure off repeated full builds when branches share much of their code.

Not every build action is a good candidate for caching. Actions that draw on random values, current time, or network calls that change frequently give unstable results. Gradle’s input tracking shields the build from unsafe reuse in those cases by skipping cache entries that do not meet its rules. Compilation and most test runs in Spring Boot projects sit on the safe side, so they usually benefit from cache reuse without surprises.

Configuration Cache in Gradle 9 for Spring Boot Builds

Configuration cache tackles a different problem. Gradle spends a real amount of time walking through every project, applying plugins, and wiring build actions together before any compilation or tests can start. Large Spring Boot projects can see that phase take several seconds or more, particularly when many modules each apply the Spring Boot plugin and several other plugins. Configuration cache gives Gradle a way to do that work a single time for a given request, store the result, and reload it quickly in later runs.

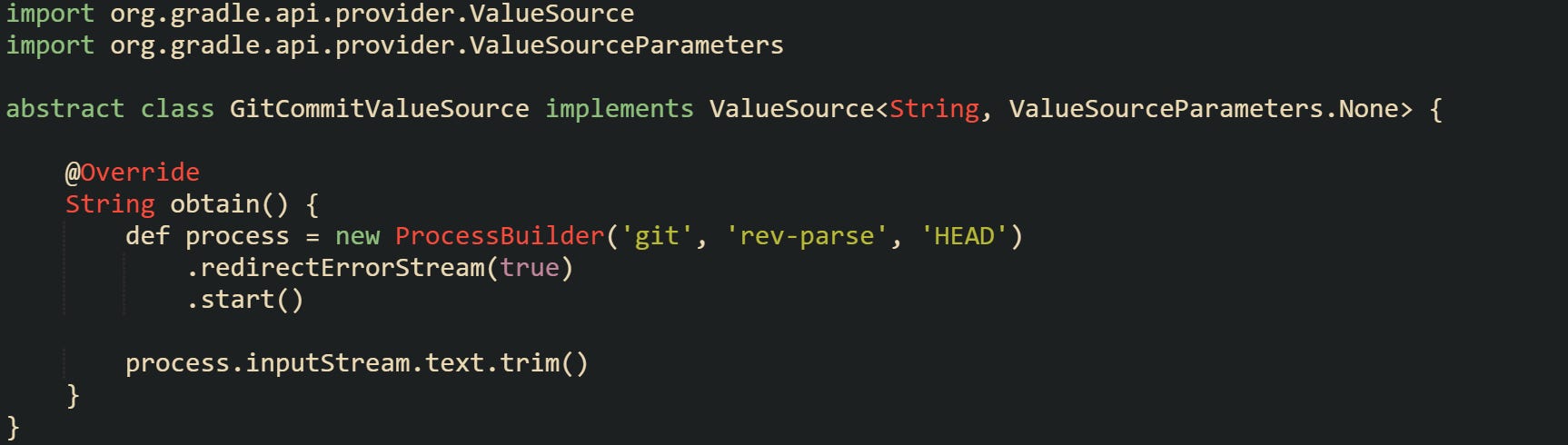

Spring Boot projects on Gradle 9 that already turned configuration cache on at the property level gain more benefit by making sure their build logic respects configuration cache rules. Gradle needs to know all inputs to configuration. Direct calls to external tools, unrestricted environment lookups, or static global state during configuration can break cache reuse. Those cases need to be reworked so Gradle can see what configuration depends on.

One pattern that fits Gradle 9 uses value sources for data such as Git commit identifiers. That keeps external process calls in a controlled, cache aware zone instead of scattering them across build scripts.

Value source code that reads the current Git commit id and exposes it to build scripts can look like this:

Build scripts that wire this extension into projects can read the gitCommit provider as part of version strings or metadata without breaking configuration cache rules. Gradle understands that this value comes from a value source, and it can track the relationship between configuration cache entries and the commit id.

Configuration cache entries sit under the .gradle/configuration-cache directory in the root project. When build logic changes in deeper ways, such as new plugins, major refactors in buildSrc, or changes in value sources, deleting that directory forces Gradle to record fresh entries. Later builds then reuse the new configuration state until the next major build logic change.

Parallel Execution in Multi Module Builds

Parallel execution takes advantage of modern hardware by letting Gradle run build actions from different projects at the same time. Multi module Spring Boot builds with dozens of largely independent services gain from this, because many modules can compile and run tests at the same time provided their dependencies do not collide.

Single builds can use parallel execution from the command line by adding the flag Gradle already understands for this purpose.

Developers who work on the same project every day usually prefer a default, so they move that preference into gradle.properties at the root.

Those two forms of configuration tell Gradle to search for build actions from different projects that can run concurrently while still honoring dependencies. Core libraries that many services depend on still need to compile before their consumers, yet unrelated services can make full use of available cores when their graphs do not overlap much.

Parallel execution sits comfortably next to configuration cache and build cache. Configuration cache reduces configuration work that repeats across runs, build cache avoids redo of identical execution work, and parallel execution keeps the CPU busy with independent actions that still remain. Projects that used older features like configuration on demand in past Gradle versions generally move away from that setting in Gradle 9 when configuration cache and parallel execution carry the load instead.

Dependency Trimming in Large Spring Boot Applications

Dependency graphs influence build performance just as much as Gradle settings. Starters in Spring Boot are convenient because one coordinate pulls in a cluster of libraries, but that convenience can lead to very broad compile and test classpaths in a big codebase. Every extra jar adds work for compilation, static analysis, test startup, and even packaging. Trimming dependencies helps Gradle and the JVM spend less time navigating code that is not actually needed for a given module.

Shared modules in a Spring Boot landscape usually do not need the full web stack. Modules that only carry DTOs and utility classes for several services can run with a narrow dependency set, while the actual API modules carry the heavier starters.

Service code that exposes an HTTP API and talks to a database could have dependencies structured like:

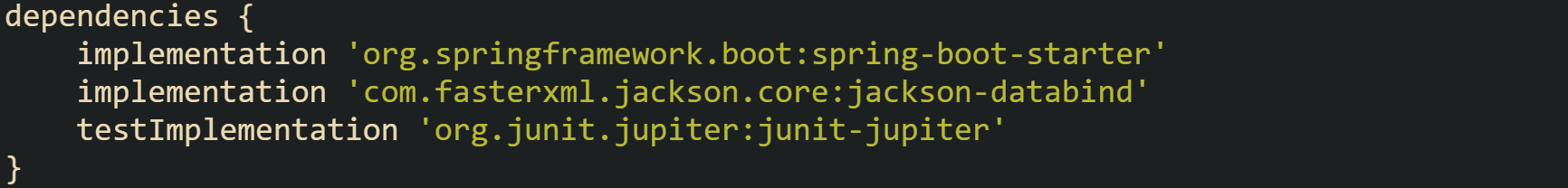

Shared model code that does not open ports or manage database connections can stay much lighter.

That contrast keeps the heavy servlet stack and JPA stack in the service module where they belong, while keeping the shared module focused on core Spring support and Jackson. Compilation of the shared module then processes fewer classes, and every service that depends on it inherits that smaller footprint.

Gradle’s dependency report gives an accurate view of what ends up on each classpath. Spring Boot projects usually care a lot about the compileClasspath for main sources and the runtimeClasspath for production builds, and sometimes about the specialized configurations for integration tests. Developers who want to inspect a module named orders-api can ask Gradle to print its compile classpath dependencies.

The report that comes out of that command lists direct dependencies and transitive ones, points out where version conflicts arise, and makes it easier to spot repeated heavy libraries that sneak in through different starter combinations. Moving some dependencies to runtimeOnly, removing unused starters, or centralizing shared dependencies through a platform or BOM import all help reduce classpath width. Spring Boot’s own BOM, brought in through its Gradle plugin, already keeps versions aligned across starters, so the main job in many projects becomes deciding which starters belong in which module.

Conclusion

Gradle 9 gives large Spring Boot builds a more mechanical way to manage time in both configuration and execution phases. Configuration cache keeps a stored graph ready for reuse, build cache brings back compiled outputs when inputs match so compilers and tests don’t repeat the same work, parallel execution keeps independent modules busy on separate cores, and careful dependency trimming keeps classpaths from growing without bound. Combined in one build, these features turn long multi module runs into smaller, predictable steps that line up with the needs of Spring Boot projects on Java 17 through 25.