Built on HTTP/2 and Protocol Buffers, gRPC gives Java services a binary contract that moves quickly between processes. Spring Boot supplies auto configuration, configuration binding, and health checks around that transport. Through a community starter, Spring based projects host gRPC servers that expose methods defined in .proto files and share generated stubs with Java clients. Those clients call the services with per call deadlines and metadata carried in headers and trailers, matching how current libraries handle timeouts and context data.

Setting Up gRPC In A Spring Boot Project

To run gRPC inside a Spring Boot application, you start by adding the right libraries, then plug in code generation so .proto contracts turn into Java classes, and finally point the embedded gRPC server at a port that other processes can reach. Spring Boot handles lifecycle and configuration, while gRPC focuses on the HTTP/2 transport and binary messages. The result is a single Spring Boot jar that opens an HTTP/2 listener and exposes strongly typed services backed by regular Spring beans.

Project Dependencies For Spring Boot gRPC

Most Spring Boot gRPC projects today build on Java 17 or later and Spring Boot 3, with gRPC Java handling HTTP/2 framing and stub support. For a Maven build, the first step is to add the Spring Boot starter, the gRPC Spring Boot starter from net.devh, and the core gRPC Java libraries that provide stubs, Protocol Buffers support, and the Netty based transport.

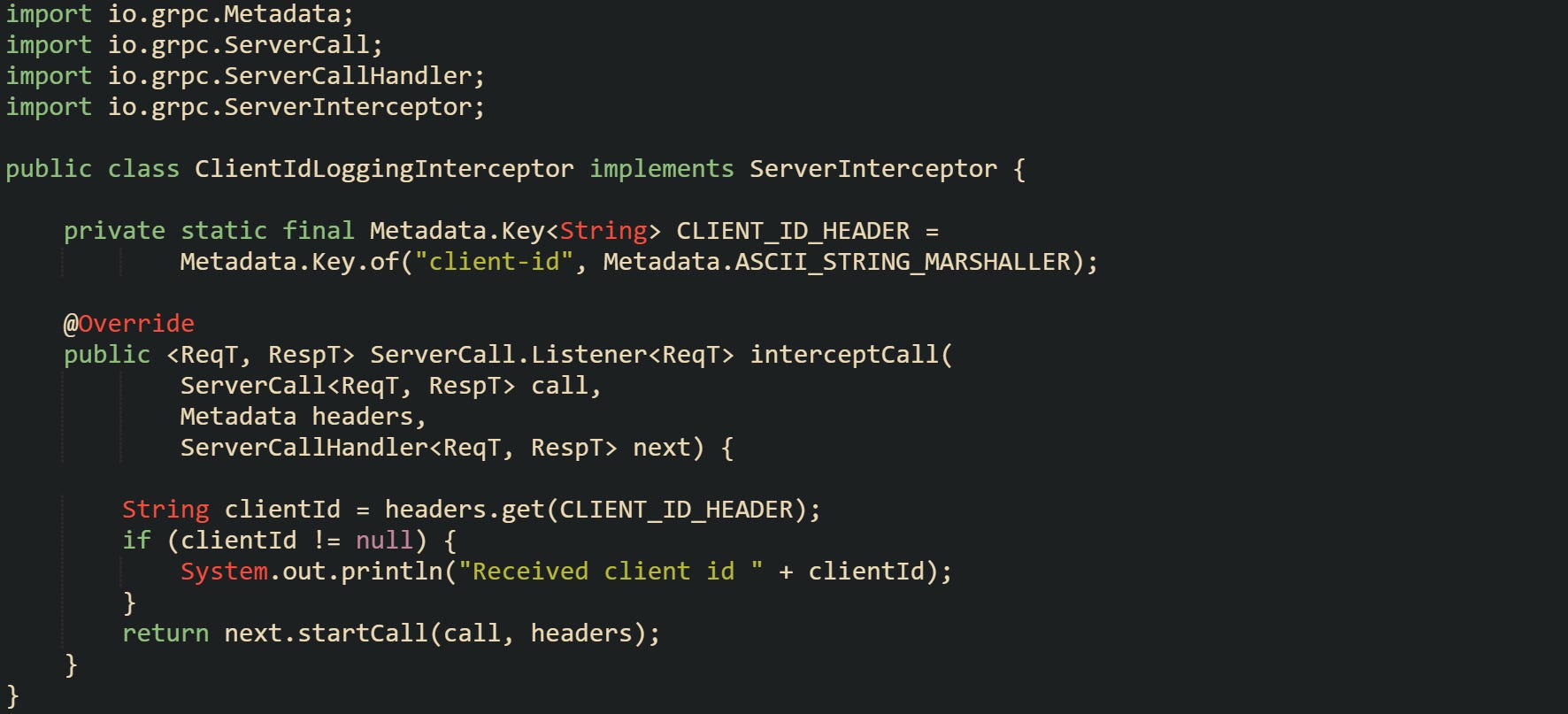

Typical pom.xml dependency entries look like this:

This set of dependencies pulls in Spring Boot, the gRPC server integration, optional client configuration, and the basic gRPC Java stack so that a Spring context can host a gRPC server and clients in the same process if needed. The grpc-server-spring-boot-starter artifact glues gRPC Java into the Spring Boot lifecycle and currently ships in the 3.1.0.RELEASE line for Spring Boot 3 based applications.

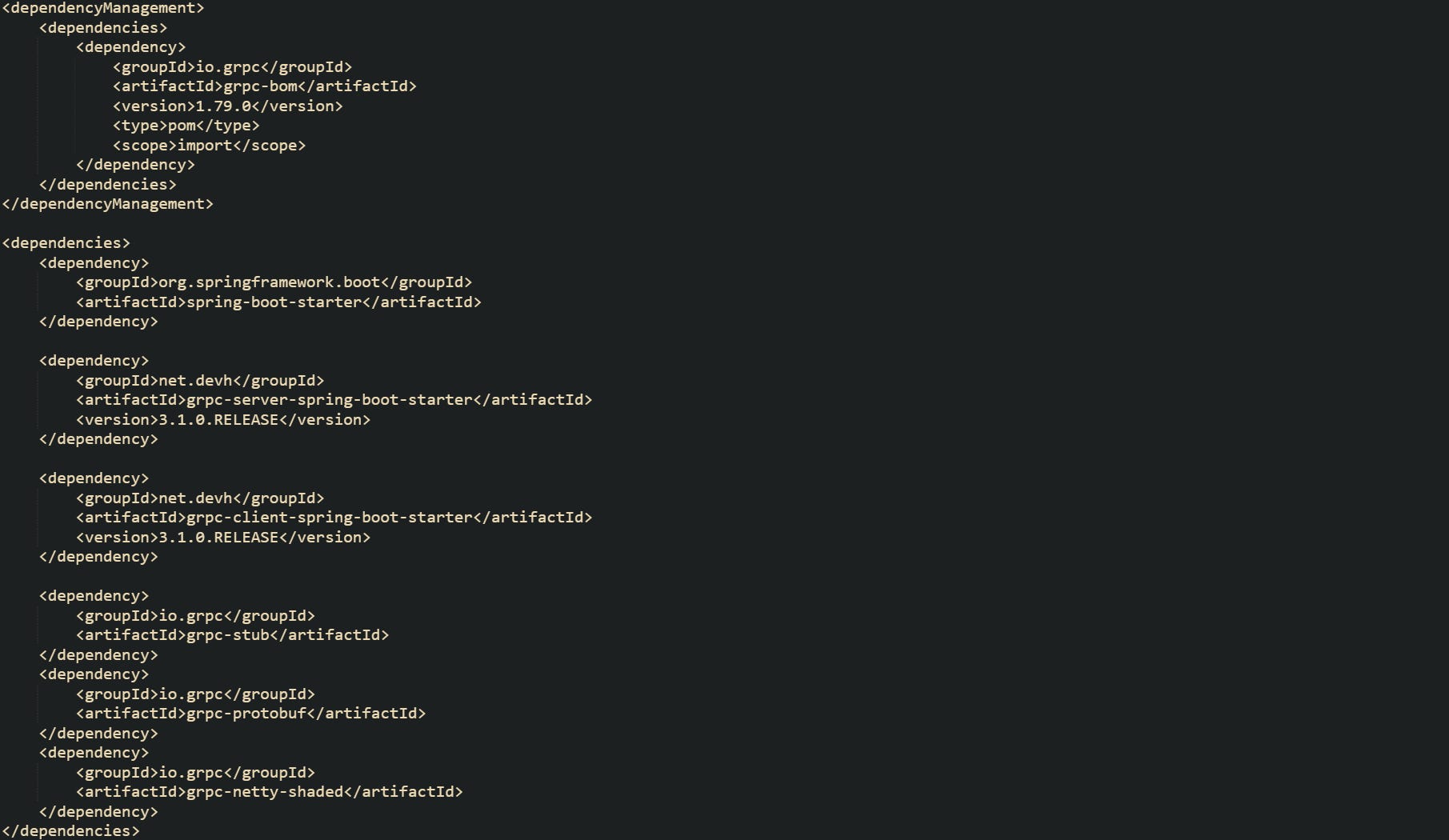

Code generation for .proto files usually runs as part of the Maven build, and the protobuf-maven-plugin from org.xolstice.maven.plugins is a common choice for that work. Take this plugin configuration that hooks protoc and the gRPC Java code generator into the compile phase:

With this plugin in place, Maven runs protoc during compile, writes Java sources for messages and service stubs into the generated sources directory, and then the normal Java compiler step picks them up like any other source files. The coordinates shown here refer to current releases of the Protocol Buffers compiler and the protoc-gen-grpc-java plugin in Maven Central.

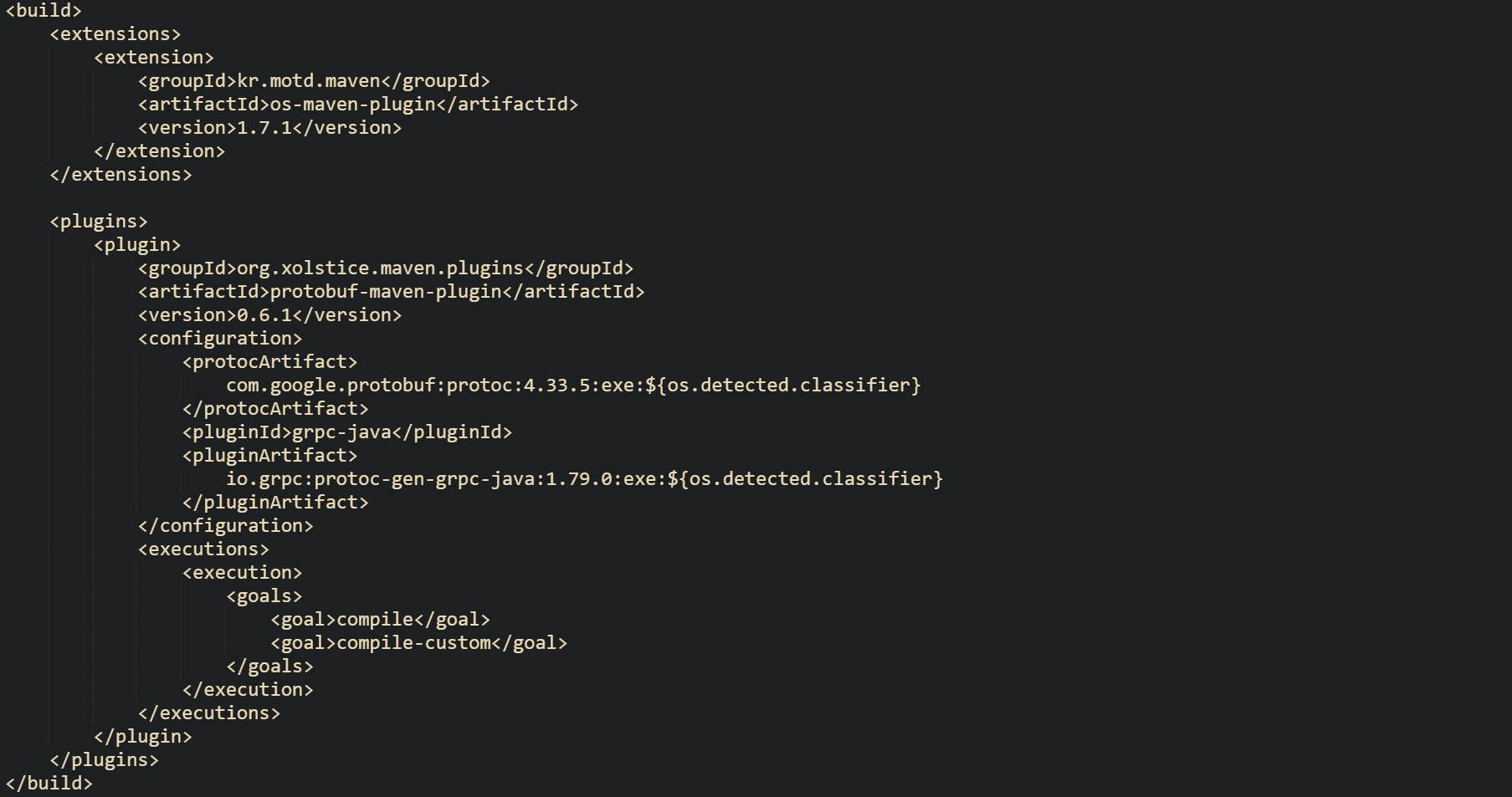

The gRPC Spring Boot starter opens its own Netty based server that sits beside the embedded HTTP port from Spring Web, and its port number comes from regular Spring configuration properties. One common choice in application.yml is a dedicated port such as 9090:

After this property is in place, the Spring Boot process listens for gRPC traffic on port 9090 while the usual HTTP endpoint from spring-boot-starter-web can stay on port 8080 or any other value you configure. The starter reads these properties through Spring Boot’s configuration binding, so changing the gRPC port is just a matter of editing the YAML and restarting the application.

Proto Contracts With Generated Java Code

Service contracts in gRPC live in .proto files that define messages and services in a language neutral way, and those files sit under src/main/proto so the Maven plugin can find them during a build. From that single definition, the generator emits Java classes for request and response types along with a *Grpc class that contains base classes for servers and client stub factories.

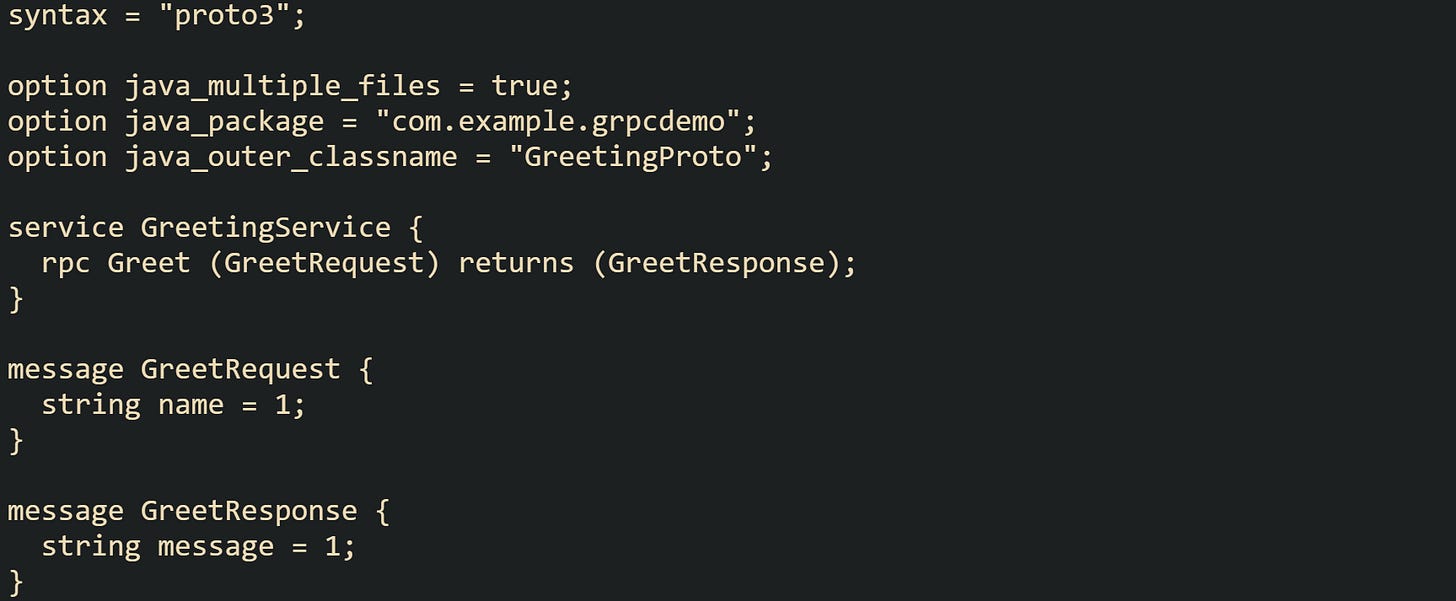

To make this make a bit more sense, let’s look at a small greeting contract for a testing server and client integration:

The syntax = "proto3" line selects the modern Protocol Buffers syntax, while the java_package and related options steer the generated classes into the com.example.grpcdemo namespace and group them under an outer class named GreetingProto. The service block declares a GreetingService interface with a unary Greet method that accepts a GreetRequest and returns a GreetResponse, and the two message blocks define the actual fields that travel on the network.

During mvn compile, the plugin runs, invokes protoc with the gRPC plugin, and writes Java sources such as GreetRequest, GreetResponse, and GreetingServiceGrpc into the target tree listed as generated sources for the build. Inside GreetingServiceGrpc, gRPC Java adds the base class GreetingServiceImplBase for servers and static factory methods like newBlockingStub and newFutureStub for clients.

Server side code in Spring Boot extends GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceImplBase and annotates the class with @GrpcService so the starter can register it.

The @GrpcService annotation marks this class as a server bean that the starter discovers at startup, and the overridden greet method reads the name from the request, builds a response message, and completes the stream with onNext followed by onCompleted. Each incoming gRPC call to GreetingService.Greet is routed by the generated glue code into this method, so the only work inside the handler is business logic and response construction.

Java Clients For gRPC Services

Client side code takes the service contract that lives in the generated *Grpc classes and turns it into outbound calls over HTTP/2. Java callers need a channel that knows how to reach the Spring Boot gRPC server, a stub constructed from the generated code, and then optional extras such as deadlines and metadata for each request. Those pieces work the same way whether the caller is a plain Java application or another Spring Boot service in the same cluster.

Client Stubs Over Managed Channels

Most Java clients start from a ManagedChannel built with ManagedChannelBuilder, then ask the generated *Grpc helper for a stub that wraps that channel. The stub handles marshalling and unmarshalling of messages, while the channel manages the underlying HTTP/2 connection and stream creation for calls. gRPC Java treats this structure as the core client side model for the library.

This client opens a plaintext channel to localhost on port 9090 and then creates a blocking stub that maps directly to unary RPC calls. The call to stub.greet wraps the GreetRequest in an HTTP/2 stream, waits for the GreetResponse, and then returns control to the caller with the decoded message. gRPC Java documents this pattern as the normal way to connect to a server from a Java process.

Many Spring Boot applications use the grpc-client-spring-boot-starter module so that stubs can be injected by name instead of created by hand. The starter brings an @GrpcClient annotation that marks a field or setter for a managed stub, and configuration properties point that logical name at a real address.

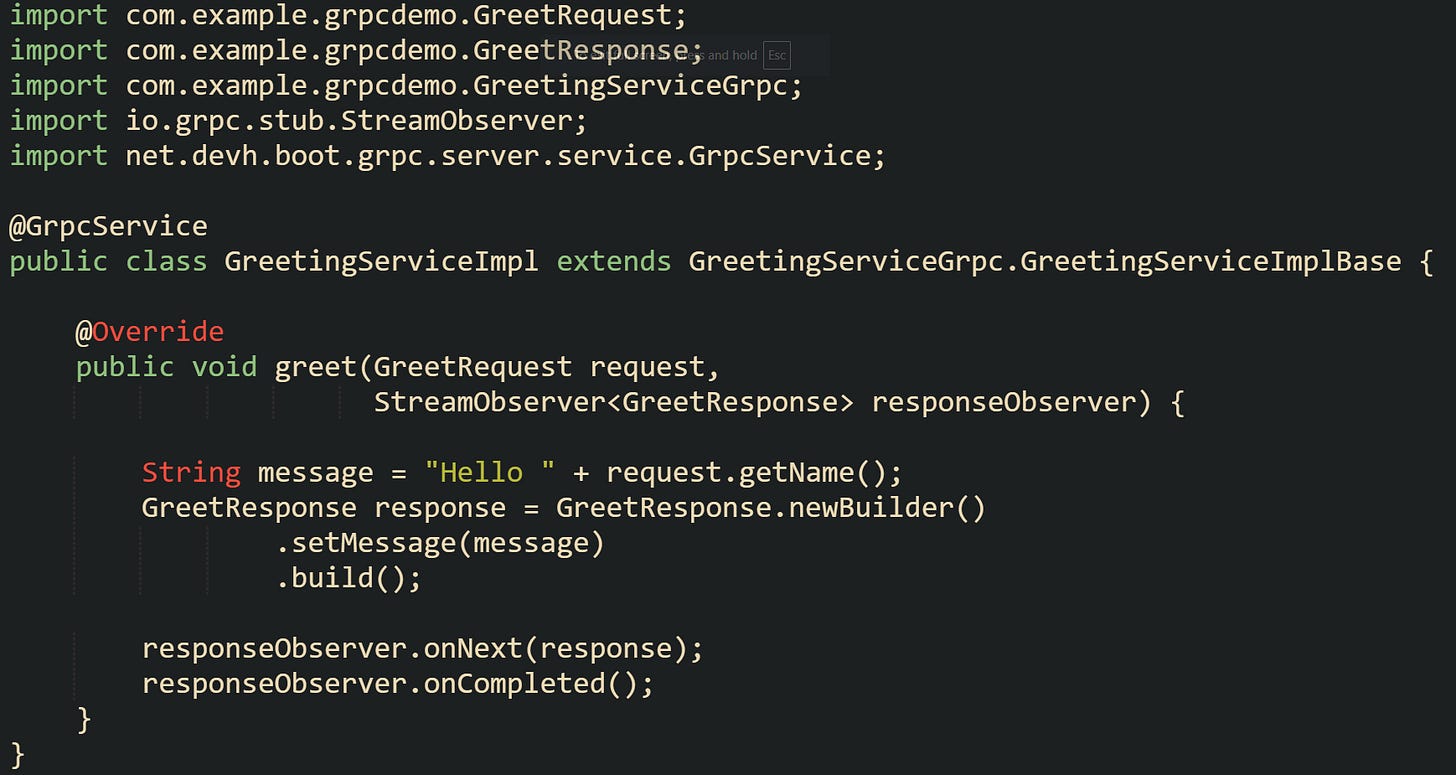

Now let’s look at a small service bean that calls GreetingService through an injected stub:

Here the @GrpcClient("greeting-server") annotation asks the starter to create and manage a channel named greeting-server with settings taken from application.yml, then build a blocking stub from that channel. Calls to greetFromClient in this Spring bean become gRPC client calls under the covers, with connection reuse and connection configuration handled through the starter.

Deadlines On Client Calls

Timeout behavior for gRPC calls is controlled through deadlines, which are time bounds specified on the client and propagated to the server. A deadline is a point in time when the client is no longer willing to wait for a response, and that value travels through the grpc-timeout header to every hop that participates in the call.

On the Java side, stubs carry deadlines through the withDeadlineAfter and withDeadline methods, and generated stubs surface withDeadlineAfter directly as a convenience on the stub.

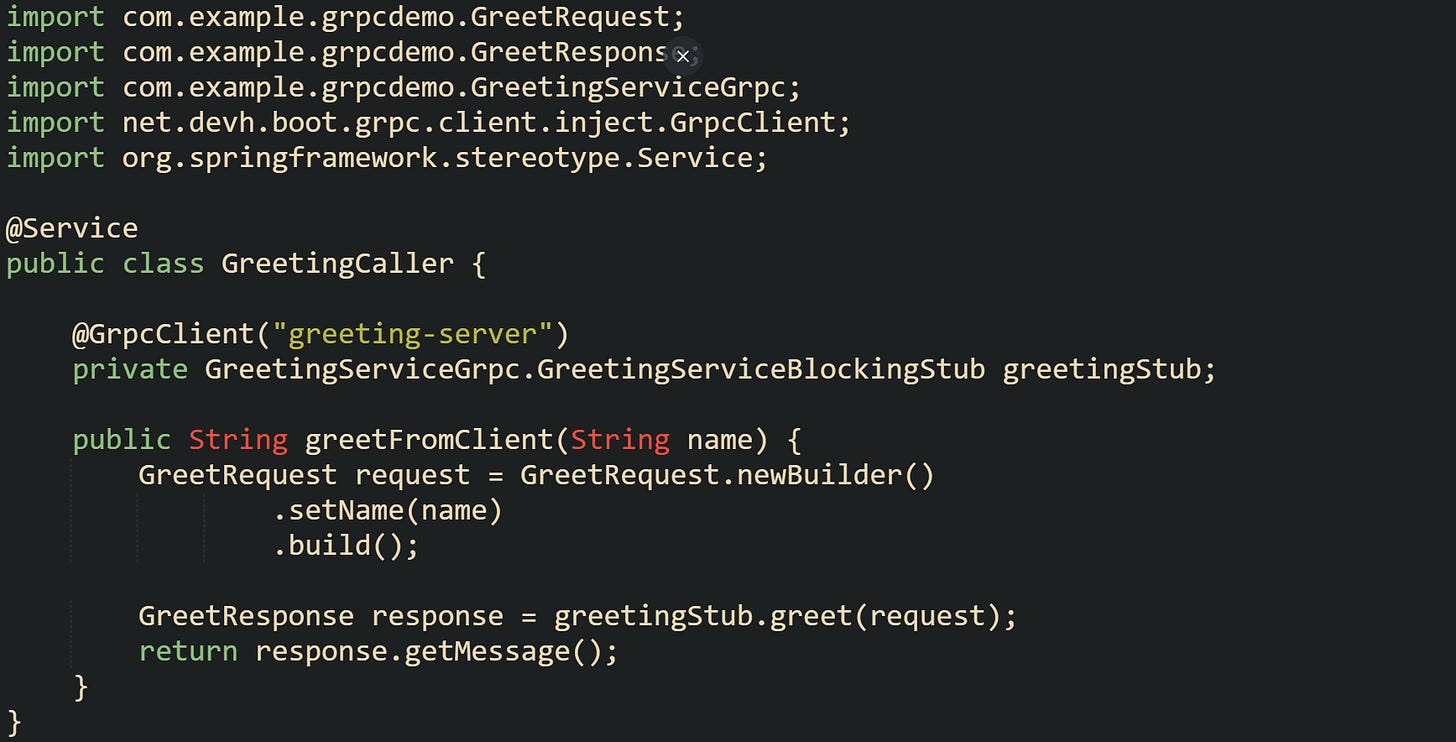

A short blocking client that sets a deadline for each call can look like this:

This client first creates a base stub on the channel, then derives a new stub with an 800 millisecond deadline. Any call made through that derived stub carries the deadline value to the server, and if the server handler does not finish in time, gRPC Java raises a StatusRuntimeException with DEADLINE_EXCEEDED. There is no universal default deadline, so clients set explicit values that fit their own services

Applications that have many call sites sometimes wrap this logic in a helper method so call sites do not repeat withDeadlineAfter everywhere. You can also make a small helper that centralizes a one second budget on a shared stub:

This helper holds a base stub that usually comes from a ManagedChannel or an injected @GrpcClient field and wraps each call in a fresh stub with an explicit deadline. Deadlines cascade through nested calls, so setting them near the call site keeps that cascade under control.

Metadata For Context Information

Metadata carries extra information such as authentication tokens, trace identifiers, or shard hints alongside the main protobuf messages. Metadata maps directly onto HTTP/2 headers and trailers and can carry both ASCII text values and binary blobs tagged with a -bin suffix. Java clients work with metadata through the io.grpc.Metadata type and client interceptors. The MetadataUtils helper in gRPC Java builds interceptors that attach headers to every call on a stub, and this interceptor based structure works well for dynamic headers that depend on the call context.

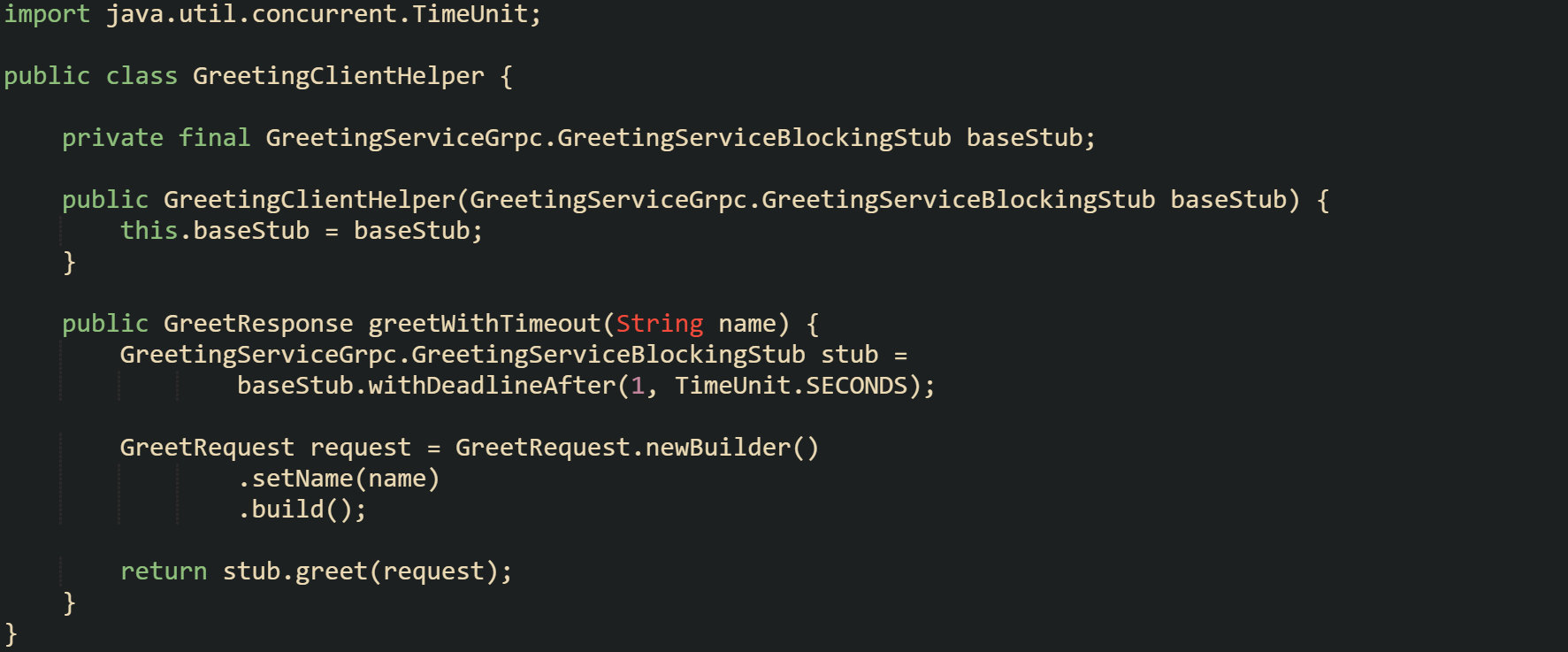

This client sends a client-id header on every call and keeps the rest of the call flow the same as earlier in the section:

In this, the client builds a Metadata instance, sets the client-id header, and then uses MetadataUtils.newAttachHeadersInterceptor with withInterceptors to produce a stub that adds that header to every call. The gRPC Java workshop and mailing list discussions show this interceptor pattern as the preferred way to attach headers for each call site.

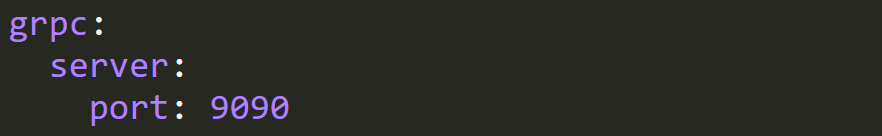

On the server side, metadata arrives through the Metadata parameter on the interceptor chain and can be inspected before the handler runs. This server interceptor logs the client-id header before passing the call on to the service implementation:

This interceptor runs on the server before the actual service implementation, reads client-id from the incoming headers when present, and passes control down the chain. The same Metadata object can also carry trailing information back to the client, which is useful for structured error details and tracing.

Conclusion

gRPC with Spring Boot turns .proto contracts into generated Java types, maps those types onto server beans through @GrpcService, and exposes them on an HTTP/2 listener backed by Netty. On the other side of the connection, Java clients build channels and stubs from the same generated classes, then control call behavior with deadlines and metadata so timeouts, headers, and trailers travel with each request. The mechanics stay grounded in a short sequence of steps where you add the starter and code generation to the build, define services and messages in .proto files, implement server methods on the generated base classes, and call those methods through stubs that carry time budgets and context for each RPC.

![import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetRequest; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetResponse; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetingServiceGrpc; import io.grpc.ManagedChannel; import io.grpc.ManagedChannelBuilder; public class GreetingClient { public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException { ManagedChannel channel = ManagedChannelBuilder .forAddress("localhost", 9090) .usePlaintext() .build(); GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceBlockingStub stub = GreetingServiceGrpc.newBlockingStub(channel); GreetRequest request = GreetRequest.newBuilder() .setName("Alex") .build(); GreetResponse response = stub.greet(request); System.out.println("Response message " + response.getMessage()); channel.shutdownNow().awaitTermination(5, java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit.SECONDS); } } import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetRequest; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetResponse; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetingServiceGrpc; import io.grpc.ManagedChannel; import io.grpc.ManagedChannelBuilder; public class GreetingClient { public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException { ManagedChannel channel = ManagedChannelBuilder .forAddress("localhost", 9090) .usePlaintext() .build(); GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceBlockingStub stub = GreetingServiceGrpc.newBlockingStub(channel); GreetRequest request = GreetRequest.newBuilder() .setName("Alex") .build(); GreetResponse response = stub.greet(request); System.out.println("Response message " + response.getMessage()); channel.shutdownNow().awaitTermination(5, java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit.SECONDS); } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Acbe!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe7e0037e-f8e7-4305-9559-a505aeece62e_1759x949.png)

![import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetRequest; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetResponse; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetingServiceGrpc; import io.grpc.ManagedChannel; import io.grpc.ManagedChannelBuilder; import io.grpc.Status; import io.grpc.StatusRuntimeException; import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit; public class GreetingClientWithDeadline { public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException { ManagedChannel channel = ManagedChannelBuilder .forAddress("localhost", 9090) .usePlaintext() .build(); try { GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceBlockingStub baseStub = GreetingServiceGrpc.newBlockingStub(channel); GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceBlockingStub stubWithDeadline = baseStub.withDeadlineAfter(800, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS); GreetRequest request = GreetRequest.newBuilder() .setName("Kaitlyn") .build(); GreetResponse response = stubWithDeadline.greet(request); System.out.println("Response " + response.getMessage()); } catch (StatusRuntimeException e) { if (e.getStatus().getCode() == Status.DEADLINE_EXCEEDED.getCode()) { System.err.println("gRPC call ran past the client deadline"); } else { System.err.println("gRPC call failed with status " + e.getStatus()); } } finally { channel.shutdownNow().awaitTermination(5, TimeUnit.SECONDS); } } } import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetRequest; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetResponse; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetingServiceGrpc; import io.grpc.ManagedChannel; import io.grpc.ManagedChannelBuilder; import io.grpc.Status; import io.grpc.StatusRuntimeException; import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit; public class GreetingClientWithDeadline { public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException { ManagedChannel channel = ManagedChannelBuilder .forAddress("localhost", 9090) .usePlaintext() .build(); try { GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceBlockingStub baseStub = GreetingServiceGrpc.newBlockingStub(channel); GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceBlockingStub stubWithDeadline = baseStub.withDeadlineAfter(800, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS); GreetRequest request = GreetRequest.newBuilder() .setName("Kaitlyn") .build(); GreetResponse response = stubWithDeadline.greet(request); System.out.println("Response " + response.getMessage()); } catch (StatusRuntimeException e) { if (e.getStatus().getCode() == Status.DEADLINE_EXCEEDED.getCode()) { System.err.println("gRPC call ran past the client deadline"); } else { System.err.println("gRPC call failed with status " + e.getStatus()); } } finally { channel.shutdownNow().awaitTermination(5, TimeUnit.SECONDS); } } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!poVY!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8076c6f8-93dc-42a6-adcc-1fa3c4c3f388_1792x898.png)

![import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetRequest; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetResponse; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetingServiceGrpc; import io.grpc.ManagedChannel; import io.grpc.ManagedChannelBuilder; import io.grpc.Metadata; import io.grpc.stub.MetadataUtils; public class GreetingClientWithHeaders { private static final Metadata.Key<String> CLIENT_ID_HEADER = Metadata.Key.of("client-id", Metadata.ASCII_STRING_MARSHALLER); public static void main(String[] args) { ManagedChannel channel = ManagedChannelBuilder .forAddress("localhost", 9090) .usePlaintext() .build(); try { GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceBlockingStub baseStub = GreetingServiceGrpc.newBlockingStub(channel); Metadata metadata = new Metadata(); metadata.put(CLIENT_ID_HEADER, "java-client-eau-claire"); GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceBlockingStub stubWithHeaders = baseStub.withInterceptors( MetadataUtils.newAttachHeadersInterceptor(metadata)); GreetRequest request = GreetRequest.newBuilder() .setName("Pippin") .build(); GreetResponse response = stubWithHeaders.greet(request); System.out.println("Response " + response.getMessage()); } finally { channel.shutdownNow(); } } } import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetRequest; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetResponse; import com.example.grpcdemo.GreetingServiceGrpc; import io.grpc.ManagedChannel; import io.grpc.ManagedChannelBuilder; import io.grpc.Metadata; import io.grpc.stub.MetadataUtils; public class GreetingClientWithHeaders { private static final Metadata.Key<String> CLIENT_ID_HEADER = Metadata.Key.of("client-id", Metadata.ASCII_STRING_MARSHALLER); public static void main(String[] args) { ManagedChannel channel = ManagedChannelBuilder .forAddress("localhost", 9090) .usePlaintext() .build(); try { GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceBlockingStub baseStub = GreetingServiceGrpc.newBlockingStub(channel); Metadata metadata = new Metadata(); metadata.put(CLIENT_ID_HEADER, "java-client-eau-claire"); GreetingServiceGrpc.GreetingServiceBlockingStub stubWithHeaders = baseStub.withInterceptors( MetadataUtils.newAttachHeadersInterceptor(metadata)); GreetRequest request = GreetRequest.newBuilder() .setName("Pippin") .build(); GreetResponse response = stubWithHeaders.greet(request); System.out.println("Response " + response.getMessage()); } finally { channel.shutdownNow(); } } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KBJ9!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcb8464dd-9ec0-4ebc-be90-9ff6b1040238_1788x926.png)