You don’t need a full programming structure like if-else to add conditional logic to a query. The CASE expression lets you write logic directly in your SELECT, WHERE, and ORDER BY clauses without extra code or table joins. It checks each condition in order and returns the first matching value. This makes it nice for shaping output based on the data itself, particularly when building reports, applying filters, or changing how columns appear based on context.

Writing Conditions With CASE

Conditional logic inside a query gives you control over how each row behaves without having to restructure your entire dataset or write multiple versions of the same query. CASE is SQL’s built-in expression for doing just that. It lets you define a set of checks and return values depending on which one passes. This all happens row by row, during the query’s execution, without needing a separate loop or control structure like if-else.

What makes CASE useful is how it fits directly into the query. You’re not writing external logic or wrapping queries in application code just to do something simple like label a value or shift a result. You just build the condition into the statement, and SQL handles it as part of the normal query evaluation.

You can use CASE to build readable, repeatable conditions inside SELECT, WHERE, ORDER BY, or even GROUP BY clauses. And since it works with both text and numbers, you’re not limited to just one kind of output.

Basic Structure

The CASE expression starts with the keyword CASE and ends with END. In between, you list out one or more WHEN conditions. Each WHEN is followed by a THEN value, which is what gets returned if that condition matches. You can add an ELSE at the end to catch anything that didn’t match, but SQL won’t complain if you leave it out. In that case, unmatched rows just return NULL.

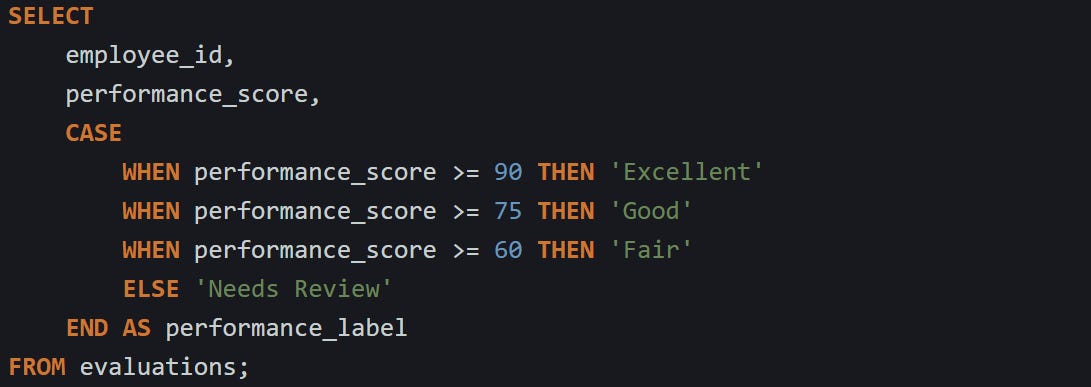

Here’s what a basic version looks like when you’re assigning categories based on a numerical score:

Each row is checked from top to bottom. SQL starts with the first WHEN, then keeps moving down until it finds one that’s true. As soon as it does, it stops and uses the value from that THEN. If none of the WHEN conditions are true and you included an ELSE, that value is returned instead. If there’s no ELSE, SQL will just return NULL for that row.

There’s no limit to how many WHEN clauses you can include, but readability is still important. Once your logic grows past a few checks, breaking it out into separate queries or functions might be better, but that depends on your case.

Searched CASE vs Simple CASE

There are two types of CASE expressions: searched and simple. A searched CASE gives you the most flexibility. You write full conditions for each WHEN, and they can be as detailed or as short as you want. That’s the kind used in the performance score example.

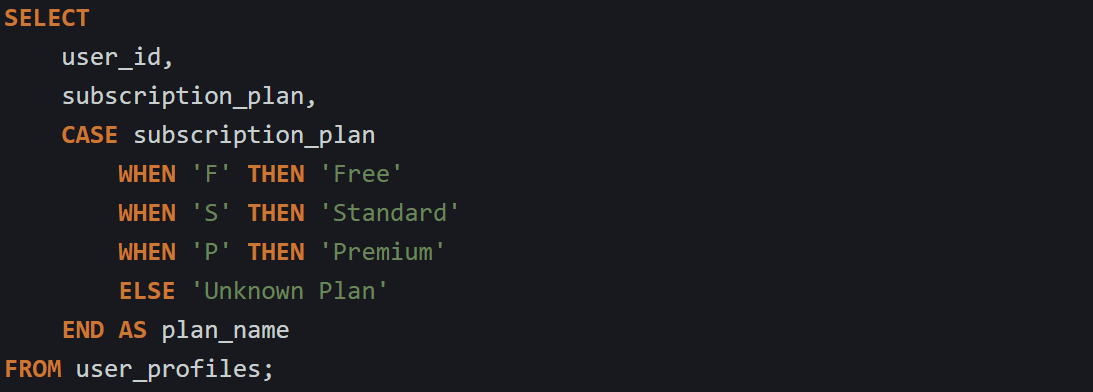

A simple CASE works a bit differently. Instead of writing full conditions, you give SQL a single value to compare against, and then write possible matches. Think of it like a switch statement in other languages.

Here’s what that looks like:

This is easier to read when you’re working with a fixed list of known values. You’re not writing full comparisons, just checking if one value matches any of a set. But you can’t add complex logic inside each WHEN like you can with a searched CASE. SQL just compares each WHEN to the original value and returns the matching THEN. Internally, both styles of CASE are evaluated the same way. The database runs each condition top to bottom until one matches. The difference is only in how you write them and what you’re comparing. You can’t mix styles though. If you start with CASE column_name, every WHEN has to match a possible value of that column. If you start with just CASE, you’re writing full conditions.

Simple CASE is great when you have status codes, categories, or any other field where the value is fixed and doesn’t need extra checking. Searched CASE gives you more flexibility and handles logic where you’re combining fields or checking ranges.

Returning Static and Computed Values

What you return from a CASE expression isn’t limited to plain text or fixed values. You can return any expression that SQL can compute. That includes numbers, strings, dates, math functions, or even results from other functions.

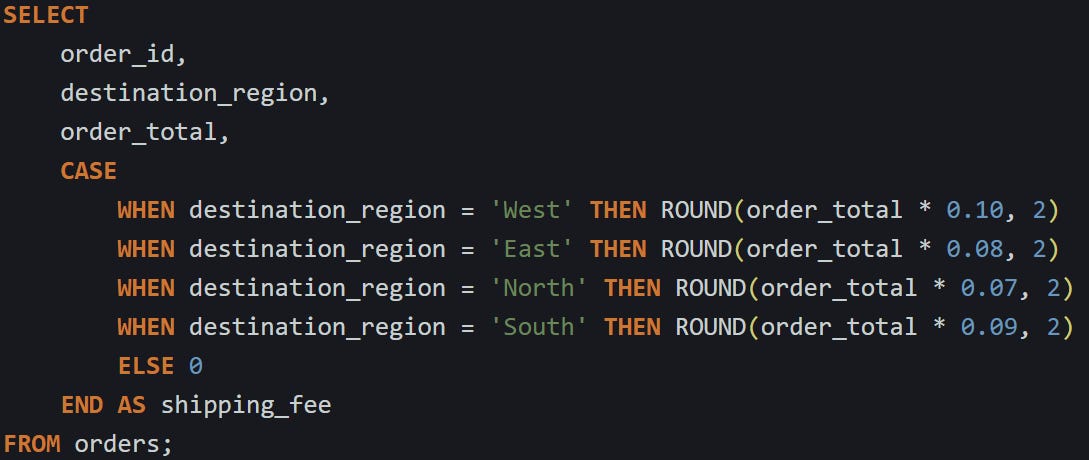

Take a look at this example that calculates shipping fees based on region:

Each region has a different percentage fee, and that’s applied directly within the THEN part of each condition. SQL does the math as part of the evaluation, and you get the final result as a column in your output. This works the same way for more complex logic too. You can combine values, call string functions, format dates, or use case-specific business rules to shape the output. CASE doesn’t limit what’s inside the THEN, as long as it results in a value.

The only restriction is that all THEN and ELSE expressions must return the same type, or types that SQL can implicitly convert to match. You can’t return a string in one and a number in another unless SQL knows how to merge them. If the types don’t line up, you’ll get an error or an implicit cast you didn’t expect.

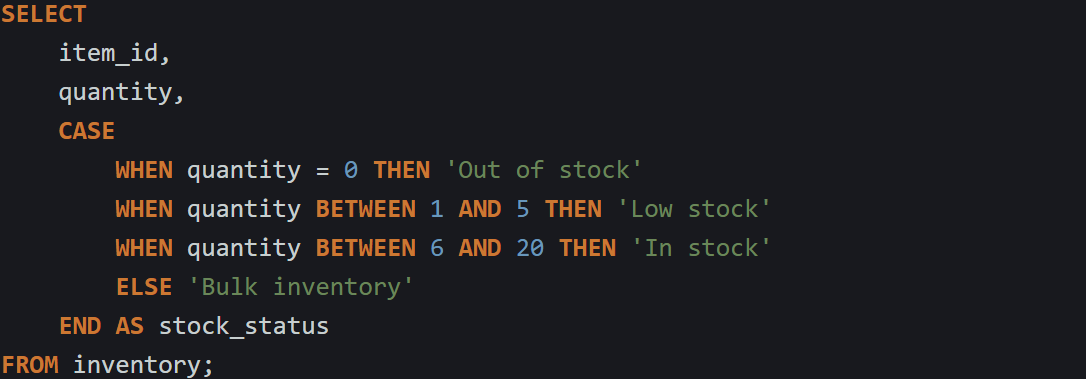

Here’s another one that returns formatted messages based on quantity:

CASE makes it easy to write messages like this based on rules that might otherwise take a lot of branching code. The whole point is to keep logic close to the data without extra structure.

It’s also worth remembering that CASE is just an expression. You can use it anywhere SQL lets you write a value. You don’t need special syntax to call it. It returns a value just like a column or a function call. That’s what makes it fit naturally into a query, especially when you need logic that depends on the row itself.

Advanced Logic With Nested CASE And Column Rewriting

When your logic begins to branch in more than one direction or the same field depends on multiple pieces of data, CASE still holds up. You can start combining expressions inside each other, apply different rules based on related columns, or rewrite values inline without adding joins. These patterns come up a lot in report queries, UI tables, and data cleanup tasks where you want to adjust what’s shown but don’t want to change the stored data.

CASE expressions keep working row by row regardless of how complex they get, which gives you a way to scale up logic without adding procedural structures or extra queries. It all comes down to how you layer the expressions and where you place them in your statement.

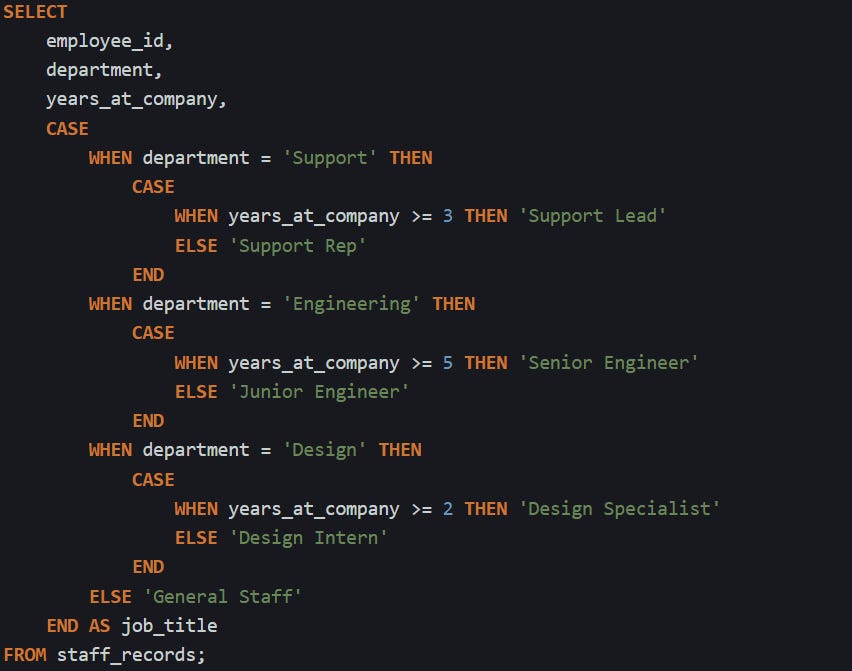

Nesting CASE Inside CASE

Sometimes a decision depends on a second detail that only matters once the first condition is already met. That’s where nesting comes in. You can put a full CASE expression inside another, usually inside a THEN, though it also works inside WHEN if needed.

Here’s an example that labels employees by both department and experience level. The job title changes depending on which branch they’re in, but each branch has its own experience threshold.

Every nested CASE expression only runs if the outer WHEN matches, so you're not checking every possible combination for every row. This makes it easier to manage categories that follow different rules but still belong to the same column in the output. SQL doesn’t do anything special here, it just evaluates each layer step by step. When the outer condition is true, it steps into the inner CASE and checks that too. There’s no difference between nesting two CASE blocks and putting them side by side. The main reason to nest is when a second decision only applies in a limited situation.

You can keep nesting deeper if your use case calls for it, though once you go more than two layers deep, it’s probably worth asking whether a lookup table or a different approach might help keep things readable.

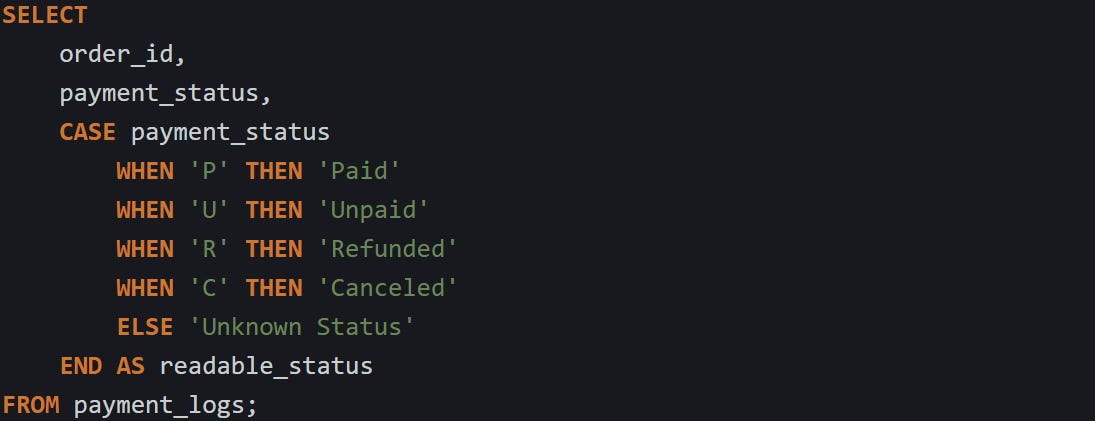

Rewriting Column Values Without Joins

A lot of tables use short codes, numeric flags, or other shorthand fields to keep data small and efficient. That’s fine for storage, but not always great for queries that return results to humans. You can clean up the output without touching the original values by rewriting them with CASE.

This is common when the possible values are stable and well known. Instead of doing a lookup join to another table just to expand codes into readable terms, you handle the replacement directly in the SELECT.

This saves you the overhead of a join, and for fields that don’t change much, it’s more convenient. CASE is stored inline and travels with the query, which makes the logic easier to maintain when your data is flat.

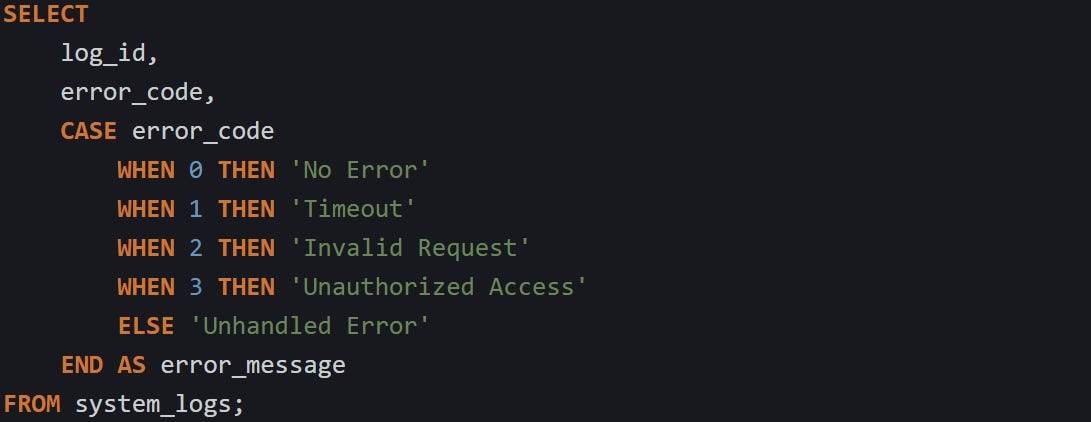

Some systems also use numeric flags, and CASE is just as helpful there. Here’s an example with error codes:

The database engine handles this kind of CASE expression the same way it does any other. There’s no memory structure or function call. SQL runs each condition row by row and matches it with the first rule that applies.

This pattern works best when you’re dealing with a small number of fixed codes. If your replacements change often or are driven by user-defined data, then a join is usually the better option. But for stable systems where the mapping is part of the logic, CASE works well.

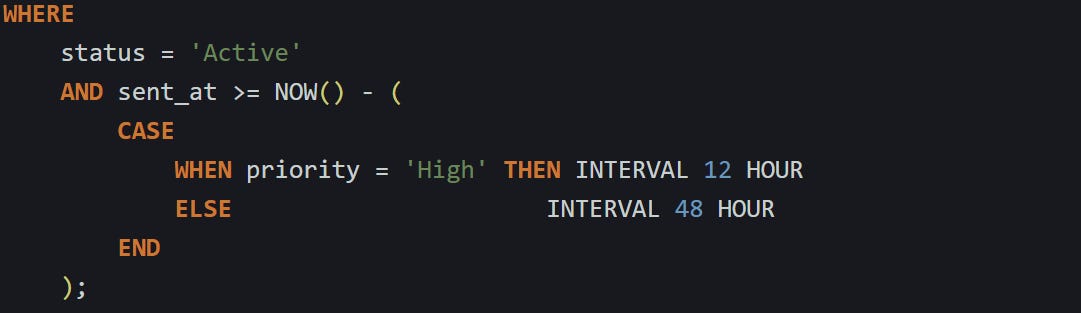

CASE In WHERE And ORDER BY Clauses

CASE isn’t limited to SELECT clauses. You can use it wherever SQL allows a value, and that includes WHERE and ORDER BY. This opens up a few useful patterns where the logic itself decides how to filter or sort the rows.

Every mainstream SQL engine lets you embed a CASE expression directly in a WHERE clause, as long as it resolves to a Boolean result, so you usually don’t need to rewrite it as a long OR block.

This means that high-priority messages get a tighter window, while others use a wider one. Without CASE, you’d have to write multiple queries or UNION different conditions, which isn’t always efficient or clean.

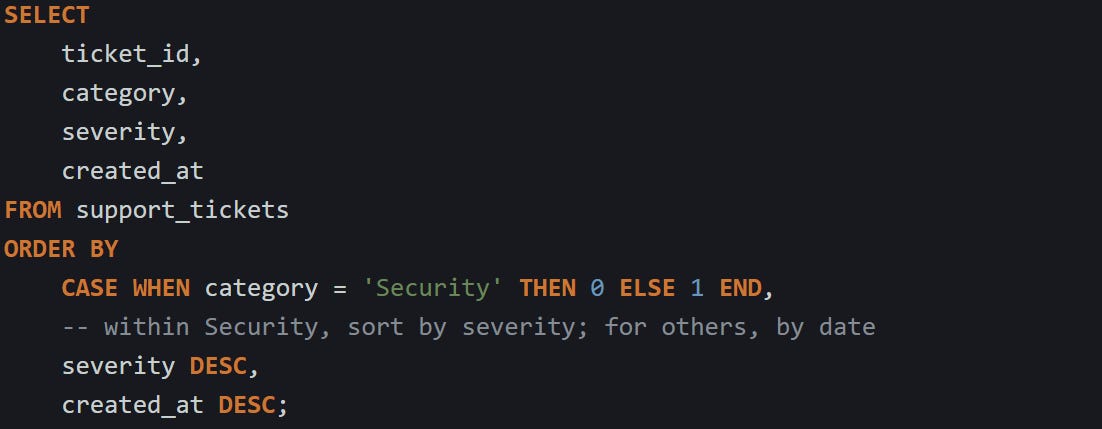

You can also use CASE in ORDER BY to control how rows are sorted based on the content. This is helpful when different types of rows should use different sort logic.

In this, security-related tickets are sorted by severity, while everything else is sorted by date. This kind of mixed sort logic can be hard to express without CASE, but it’s handled natively, though the expression can prevent an index on the sorted columns from being used. The database evaluates the CASE for each row, figures out the result, then sorts accordingly.

If you do embed CASE in a WHERE clause on engines that allow it, make sure the expression resolves to a Boolean condition, not a label or string.

Shortcuts Using CASE With Booleans

CASE pairs naturally with boolean expressions. You’re often checking flags, conditions, or simple on-off states, and CASE gives you a way to turn those into usable values or indicators inside your query.

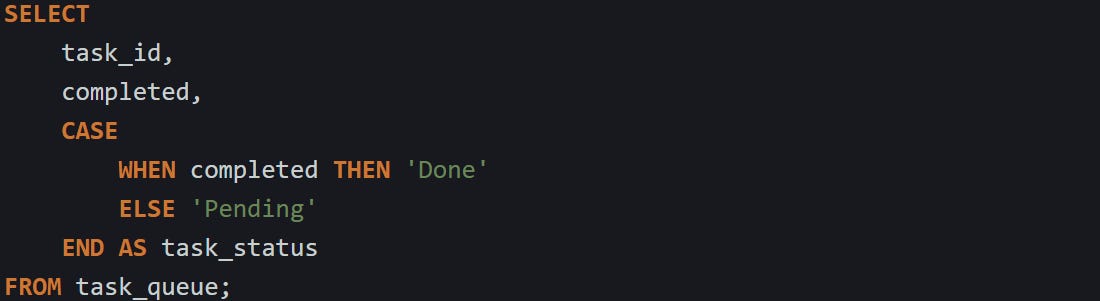

Sometimes the check itself returns true or false, and you just want to turn that into a number or label.

You don’t have to write = TRUE if the column is already a boolean. SQL accepts the bare column name as a condition, and if it holds a true value, the WHEN clause matches.

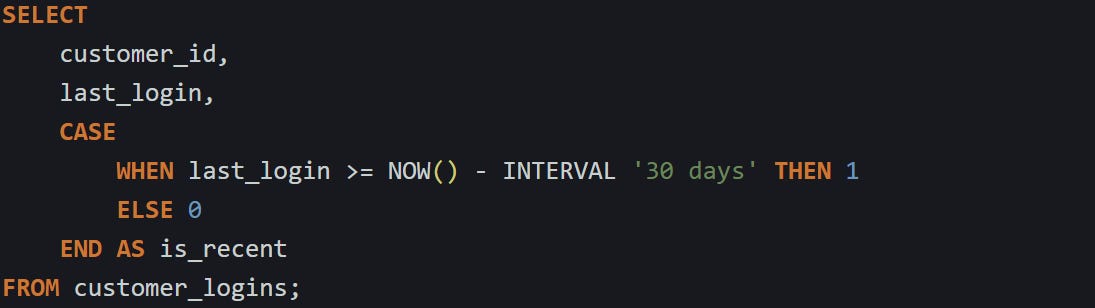

Another common use is returning numeric flags that you can later group by, count, or filter on.

This gives you a simple way to tag records without making structural changes to the table or adding computed columns. It also lets you pipe the result straight into other queries, reports, or dashboards.

CASE doesn’t change behavior when working with booleans. It still reads top to bottom, picks the first match, and returns the value tied to that condition. When the input is already boolean, though, the conditions get shorter and easier to scan. And if you’re only working with two states, you can switch to the simple form: CASE completed WHEN TRUE THEN 'Done' ELSE 'Pending' END, this keeps the code short without losing the required WHEN.

Conclusion

CASE gives you a way to shape your results right where the data lives. It moves through the checks you give it one at a time and returns whatever matches first. That happens for every row, right during the query. You can nest conditions, swap out codes for labels, switch how records are sorted, or add logic to filters without jumping through extra steps. It’s built into how SQL runs, so it doesn’t need special rules to work. You write the logic, and the database runs it with the rest of the query, row by row, without extra layers.