Production databases tend to carry queries that feel slow even on strong hardware, and index hints give database engineers a direct way to override the optimizer when its choices do not match the actual data distribution or traffic behavior, so engineers can steer specific statements toward index plans that trim I O and response time.

How Index Hints Affect Query Plans

Index hints sit inside query text and tell the optimizer how to treat specific indexes. Without hints, the engine reads statistics, builds several candidate plans, and picks the one that looks cheapest in terms of I O and CPU cost. With hints, that search space narrows, because certain indexes are pushed to the front or removed from the options entirely. MySQL and SQL Server both follow this broad idea, even though their hint syntax and details differ.

These hints do not turn off the optimizer. The engine still has to decide join order, join algorithms, sort strategies, and many other details. Hints mainly control which access routes are allowed for a table, such as a full scan, a seek on an index, or a scan of a covering index. That makes them a precise tool for queries where the planner repeatedly picks an index that works poorly with real data statistics.

What Query Optimizers Do

Database engines treat a text query as a starting point for building an execution plan. The first step turns the string into a parsed tree, which records tables, columns, predicates, and join conditions in a structured form. That tree may expand views and inlineable subqueries so that the optimizer can reason about a single, unified plan instead of many smaller fragments. After parsing, the optimizer reads metadata. It checks which indexes exist on each table, what columns those indexes contain, and what kind of statistics are available on base tables and indexes. Histograms and density values stored with statistics give the planner a way to estimate how many rows match a predicate such as status = 'ACTIVE' or order_date >= '2026-01-01'. Those row count estimates drive almost every later decision, because they determine how much work each part of the plan must do.

When metadata and statistics are in hand, the planner starts building alternative plans. One candidate may scan an entire table and apply a filter to every row, while other candidates seek into selective indexes and touch only a small slice of the data. Further variation appears around join order and join type. The engine can join customers to orders in more than one sequence, and it can choose nested loops, hash joins, or merge joins based on estimated row counts and sort properties.

Indexes enter this process as access options for a table. One table that has three secondary indexes and a clustered index presents several possible access patterns, including a full scan of the clustered index and different seek or scan patterns on each secondary index. Without hints, the optimizer weighs all of them and keeps the ones that look most promising. With hints, that list shrinks, which guides the final plan toward specific indexes.

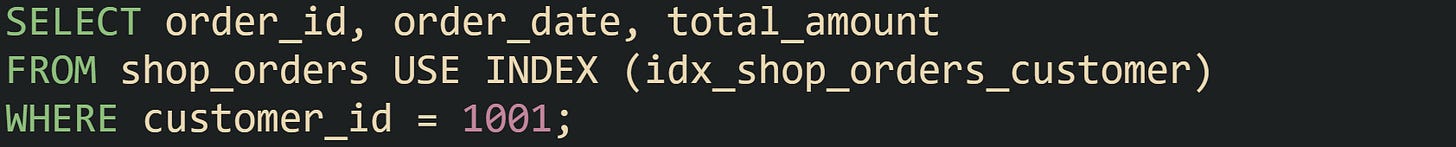

MySQL offers hints such as USE INDEX, FORCE INDEX, and IGNORE INDEX inside the FROM clause. These apply to SELECT and UPDATE statements and to multi table DELETE statements, and they can also be scoped to phases like join planning, ordering, or grouping. Newer MySQL releases also document index level optimizer hints meant to replace these, with USE INDEX, FORCE INDEX, and IGNORE INDEX expected to be deprecated in a future release. Here is a small example with USE INDEX:

This query still goes through normal planning, but the hint tells MySQL to favor idx_shop_orders_customer for access to shop_orders and to push other indexes to the side for this statement.

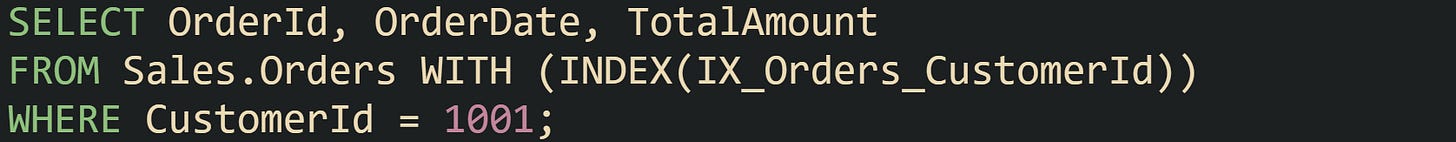

SQL Server applies table hints by placing WITH (hint options) immediately after the table name. One common form is the INDEX hint that directs planning to a specific index identifier or name:

That hint does not fully lock down the plan, yet it steers the optimizer toward IX_Orders_CustomerId when it decides how to read Sales.Orders. Other parts of the plan, such as join choices and sort operations, still come from the usual cost based process.

Index Selection With Statistics

Statistics sit at the core of index choice. Each index and base table can have statistics objects that record how values are spread across the column domain. Histograms on columns such as status can reveal that only a small fraction of rows use a value like 'PENDING_REVIEW'. Density values for a composite index on (customer_id, order_date) can show how many different combinations exist in the table. Planners rely heavily on these numbers when they decide which index to use.

When a predicate references columns with up to date statistics, the engine can estimate selectivity for each index that covers those columns. If a filter on customer_id and order_date is expected to match only a small band of rows, a composite index on those columns looks attractive. If statistics indicate that almost every row matches a predicate, the planner may prefer a scan, because seeking into an index would just add overhead without much benefit.

Problems appear when statistics no longer match reality. Data can change dramatically after a bulk load, seasonal spike, or archival process. Skewed distributions can also confuse the planner. Think about a flag column with values that are almost always zero, apart from a tiny active slice. Queries that focus on the rare slice can perform well with a selective index, while queries that touch the common slice behave badly if the engine misjudges how many rows will match.

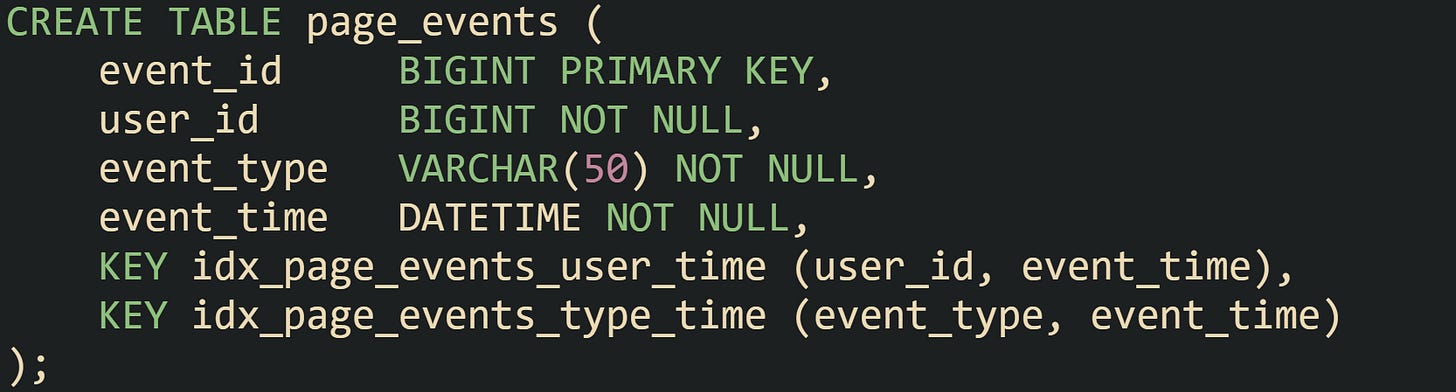

Let’s take a look at a MySQL example of this, say we are working with a logging table that holds web events:

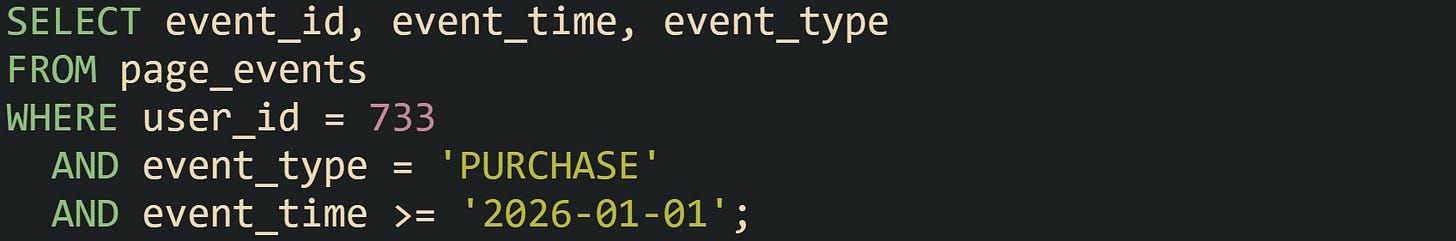

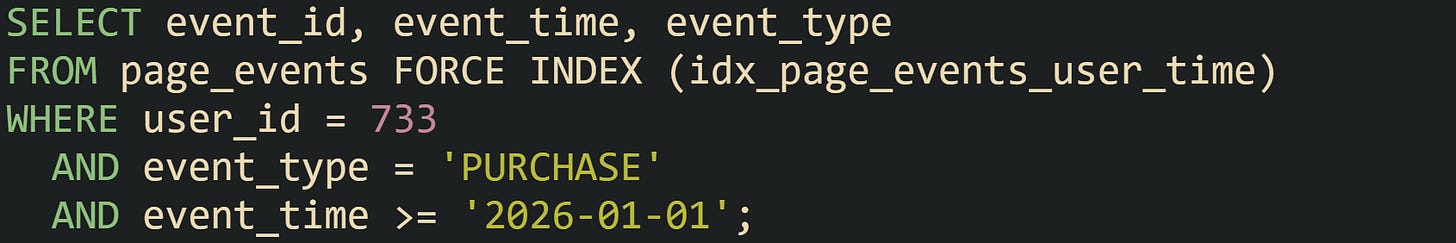

Suppose most rows have event_type = 'PAGE_VIEW', while rare events such as event_type = 'PURCHASE' form a tiny minority. One query that hunts for recent purchase events by a single user can be:

If statistics on event_type and user_id do not reflect the true distribution, MySQL may misjudge which index will touch fewer rows. The planner may pick idx_page_events_type_time when that index leads to many more reads than a targeted seek on idx_page_events_user_time for this query shape. Index hint use can nudge the engine toward the composite index on user_id and event_time.

That hint tells MySQL to center its plan on idx_page_events_user_time for access to page_events. The predicate on event_type still applies, but now it filters rows that already passed the user_id and event_time filter driven by the composite index.

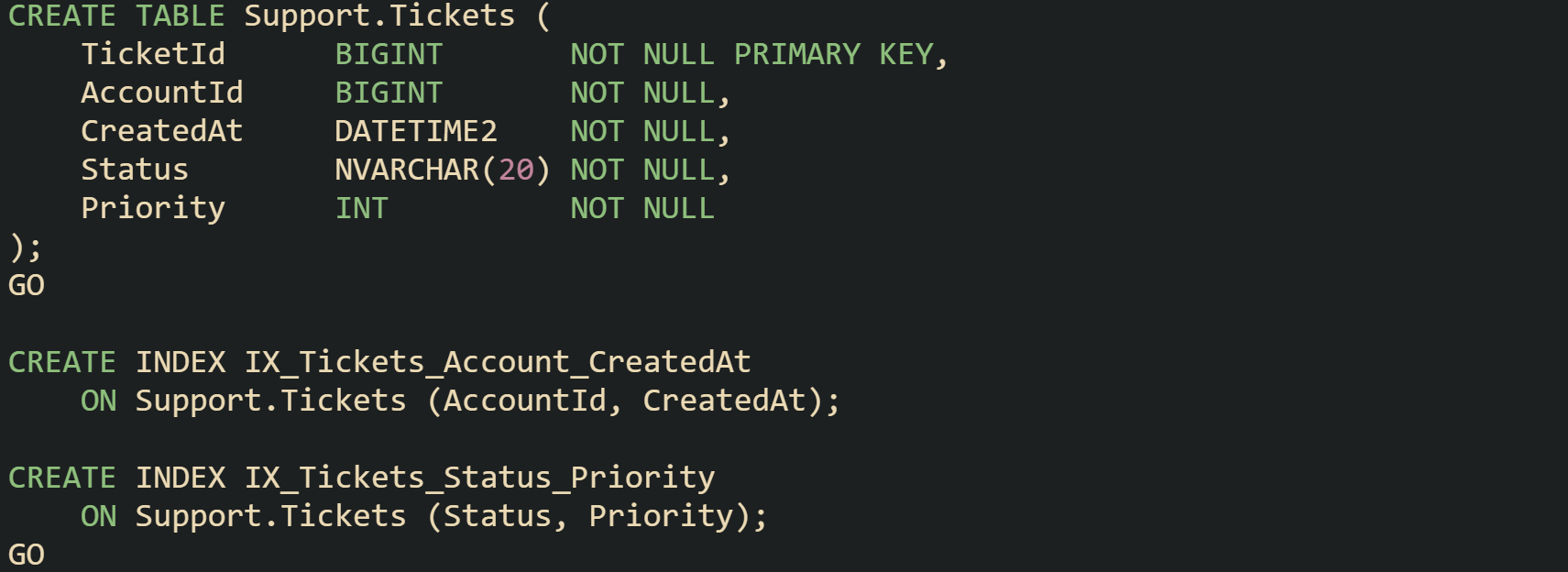

SQL Server runs into the same category of problem. Say there is a table for support tickets:

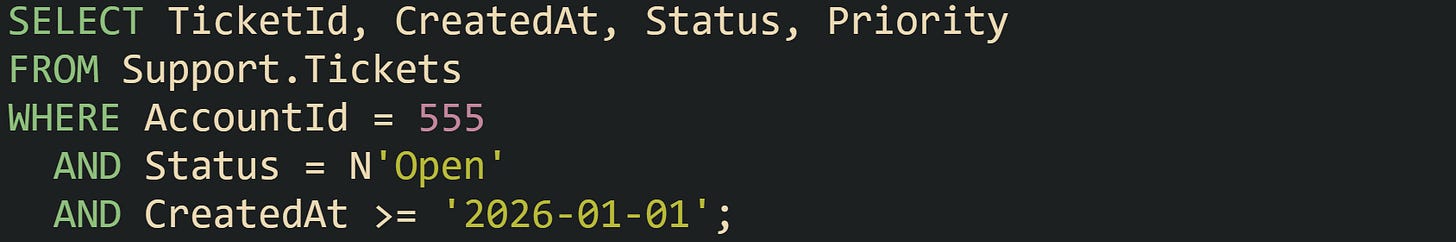

Think about a report that focuses on open tickets for a single account in a recent date range:

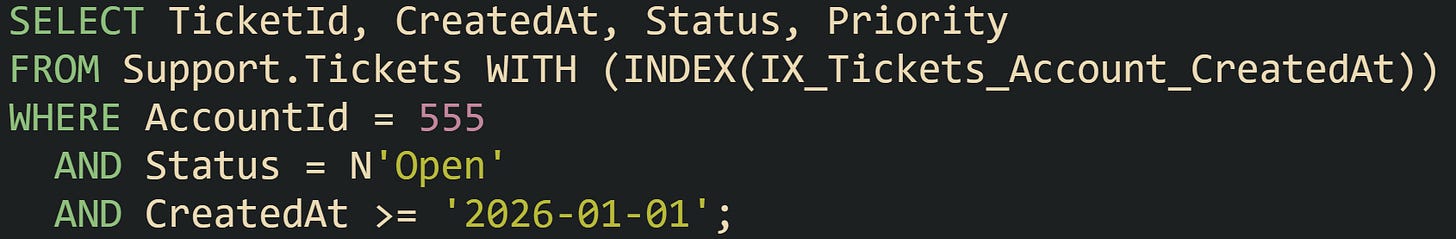

Depending on statistics, SQL Server may gravitate toward IX_Tickets_Status_Priority and then apply the AccountId filter as a residual predicate. If that index leads to a large scan, a table hint can direct the engine back toward the composite index centered on AccountId:

This version tells the optimizer to base access on IX_Tickets_Account_CreatedAt. The statistics on that index still matter, but the hint removes other indexes from the competition for this table inside this query.

Risks Of Forcing Index Choices

Hints that steer index choice help with stubborn slow queries, yet they bring tradeoffs that are easy to overlook. Every hint hard codes an assumption about data distribution, workload habits, and index layout. As months pass, tables grow, data skews change, and administrators add or drop indexes. That hint can later turn into a liability when those assumptions no longer hold. Limited flexibility is one of the biggest side effects. Without hints, the optimizer can generate different plans for different parameter values, storage layouts, or statistics states. It can pick a selective index for rare values and a scan for common ones. With a forced index, that freedom shrinks. The planner must keep the hinted index in the plan, even for parameter values that would benefit from a different route through the table.

Schema changes get more awkward when index hints spread through application code, because dropping or renaming a hinted index affects not only the optimizer’s choices but can also cause queries to fail at parse time, forcing database engineers to comb through code bases and stored procedures to update or remove those hints before they can safely adjust index definitions.

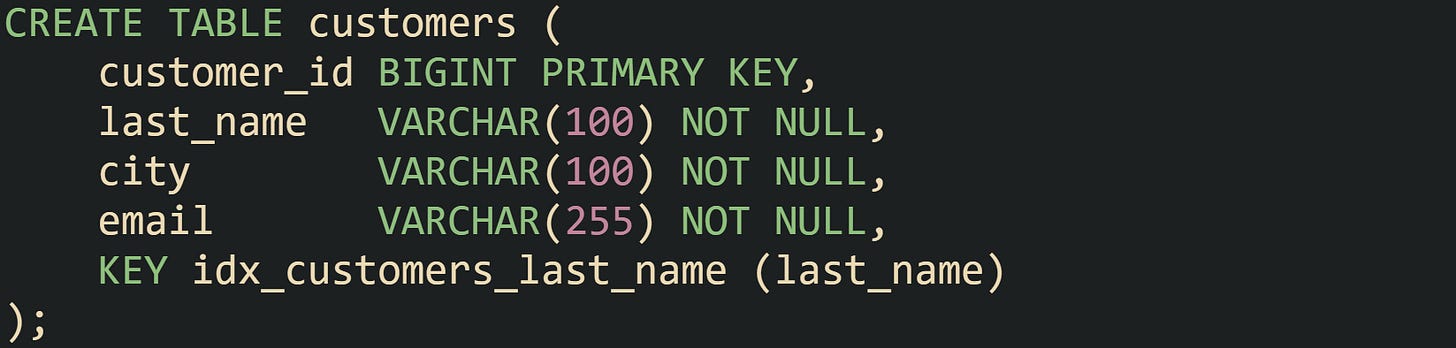

Say we work with a customer table in MySQL that once relied on a narrow index on last_name to support specific reports:

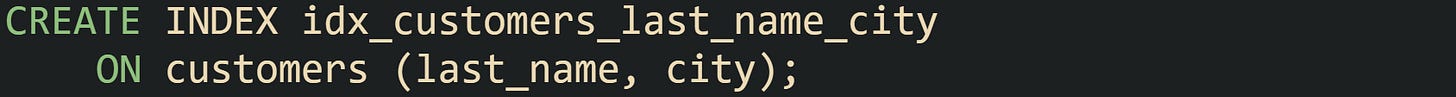

At some point new reporting needs lead to a wider composite index.

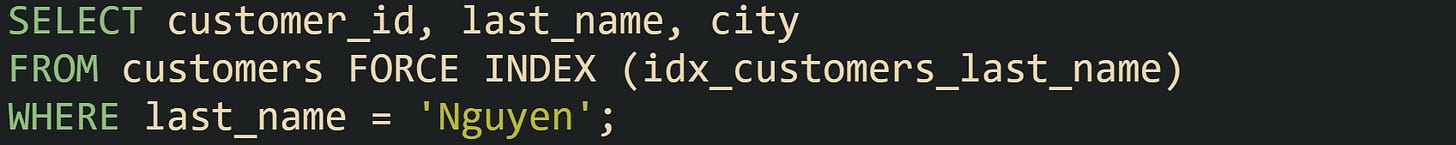

If an early version of the reporting query had a hint like this:

And later the engineering group decides to drop idx_customers_last_name because idx_customers_last_name_city serves modern reporting better, that hint turns into a problem. Dropping the index without touching the query causes MySQL to raise an error, because the hint now references an index that no longer exists.

SQL Server faces similar issues with long lived table hints. Index hint use that names a specific index id or name needs a code change whenever index definitions move. Hint heavy code bases tend to slow down index tuning work, because every change requires coordination between database administrators and application developers.

For these reasons many engineering groups reserve index hints for specific pain points, document them carefully, and revisit them during major schema or workload changes. Better index choices, fresher statistics, and query rewrites usually carry less long term risk than a broad wave of forced index selection across an entire application.

Hands On Index Hint Examples

Query tuning makes more sense when you see the shape of an actual table, an actual query, and the plan that the optimizer picks. Index hints come into play when those plans stay slow even after you create reasonable indexes and let statistics update. The examples here stay focused on read queries, because those are common in reporting and web backends, and they give you a direct way to see how hints tie into EXPLAIN output and execution plans.

MySQL Index Hint On A Read Query

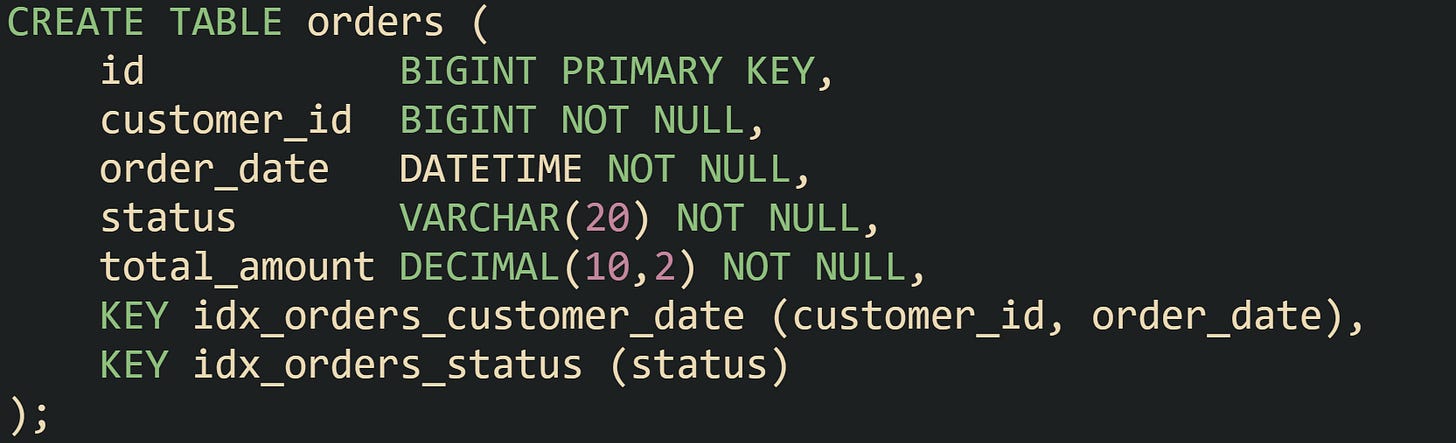

You will often see MySQL applications track customer purchases in a table that grows every day. Indexes help keep recent history queries fast, but the optimizer still has choices that do not always line up with how the data is distributed. As one case, take this table that records orders from an online store:

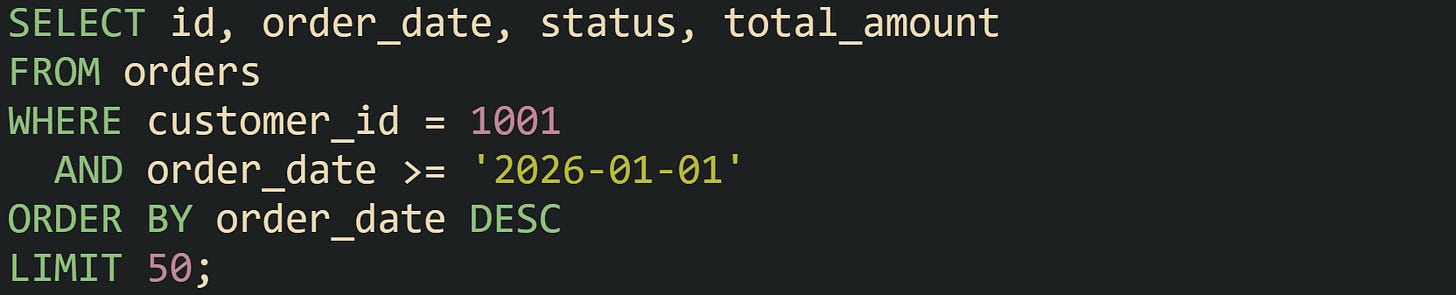

Assume most traffic comes from screens that show recent orders for one customer at a time. A read query can look like this:

On a large table with a good composite index, a plan that seeks into idx_orders_customer_date, walks back through recent dates for that customer, and stops after 50 rows keeps I O relatively low. That path lines up with the filter and the sort order. On some data sets, though, MySQL estimates that many rows will match and quietly chooses a full table scan.

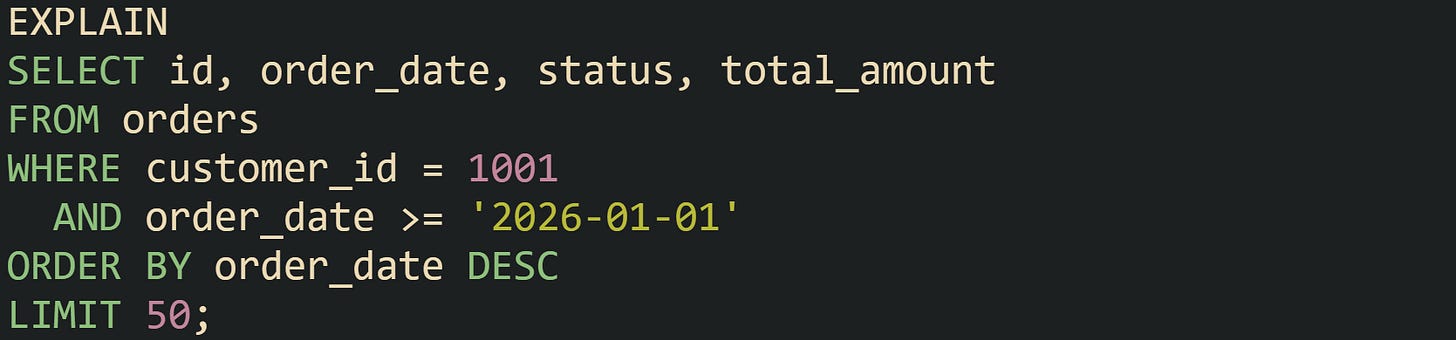

Running EXPLAIN on the same text makes that choice easier to see:

One run against a table with about a million rows can produce a row that reports type = ALL, rows = 1000000, and an Extra field that mentions a filesort. That combination means the engine walks the whole table, applies the filter to every row, sorts the survivors on order_date, and finally discards all but the first 50. On modest hardware that kind of plan can sit in the few hundred millisecond range whenever the buffer pool does not already hold the needed pages.

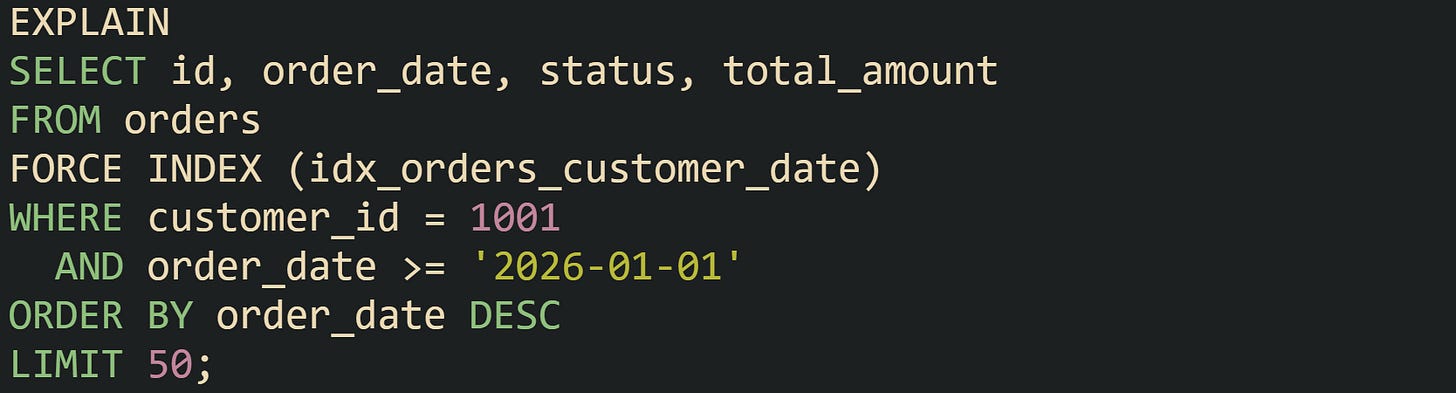

Index hints give you a way to push the optimizer toward the composite index. The hint becomes part of the query text and stays under version control with the rest of the application.

With that hint in place, EXPLAIN tends to report type = range or ref, the key column moves to idx_orders_customer_date, and the rows estimate drops sharply, sometimes into the low hundreds on realistic data. That change reflects a new access route where MySQL seeks directly into the slice of the index that matches customer_id = 1001 and the date range. The engine still has to read base table pages for the selected rows, yet it avoids touching the entire table and also avoids sorting all matching rows in memory or on disk.

On a basic test instance with data in that range, queries that follow the hinted plan can land in the tens of milliseconds, because they only read the portion of the index that satisfies the filter and sort requirements. Timings always depend on hardware and load, but the mechanical reason stays the same. The hint makes the optimizer treat the composite index as the primary route into orders and narrows the number of candidate plans that involve full scans.

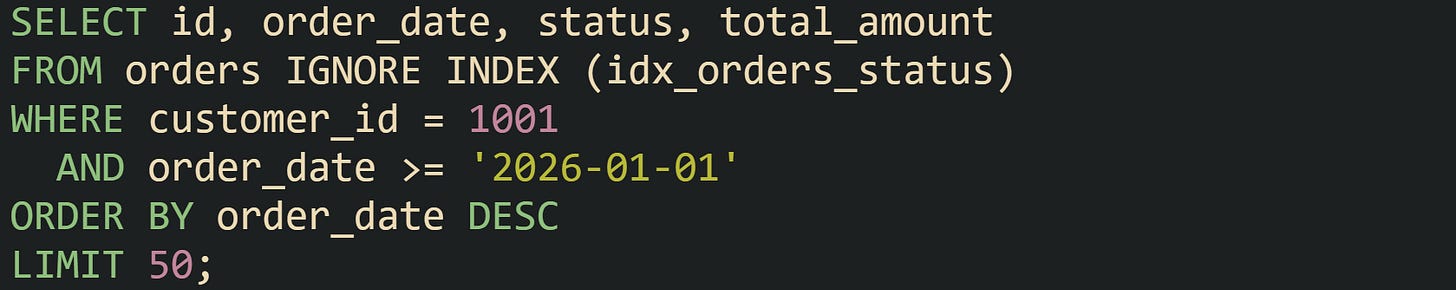

MySQL also supports the reverse move, where you tell the optimizer to ignore one or more indexes that tend to drag plans in the wrong direction. Queries that suffer from an unhelpful status index can be written like this:

That change forces the planner to treat idx_orders_status as unavailable for the duration of that statement. The remaining choices still go through cost based planning, but the hint removes one distracting option from the search space, which can guide MySQL toward access paths built on idx_orders_customer_date without fully locking it into a single index name.

SQL Server Index Hint Through Table Hints

SQL Server tends to appear in environments that lean on reporting queries and mixed workloads, so table hints interact with a wider range of query plans. Index hints come through the WITH (hint options) clause after a table reference and can nudge the optimizer toward indexes that track business filters more closely than its default choice.

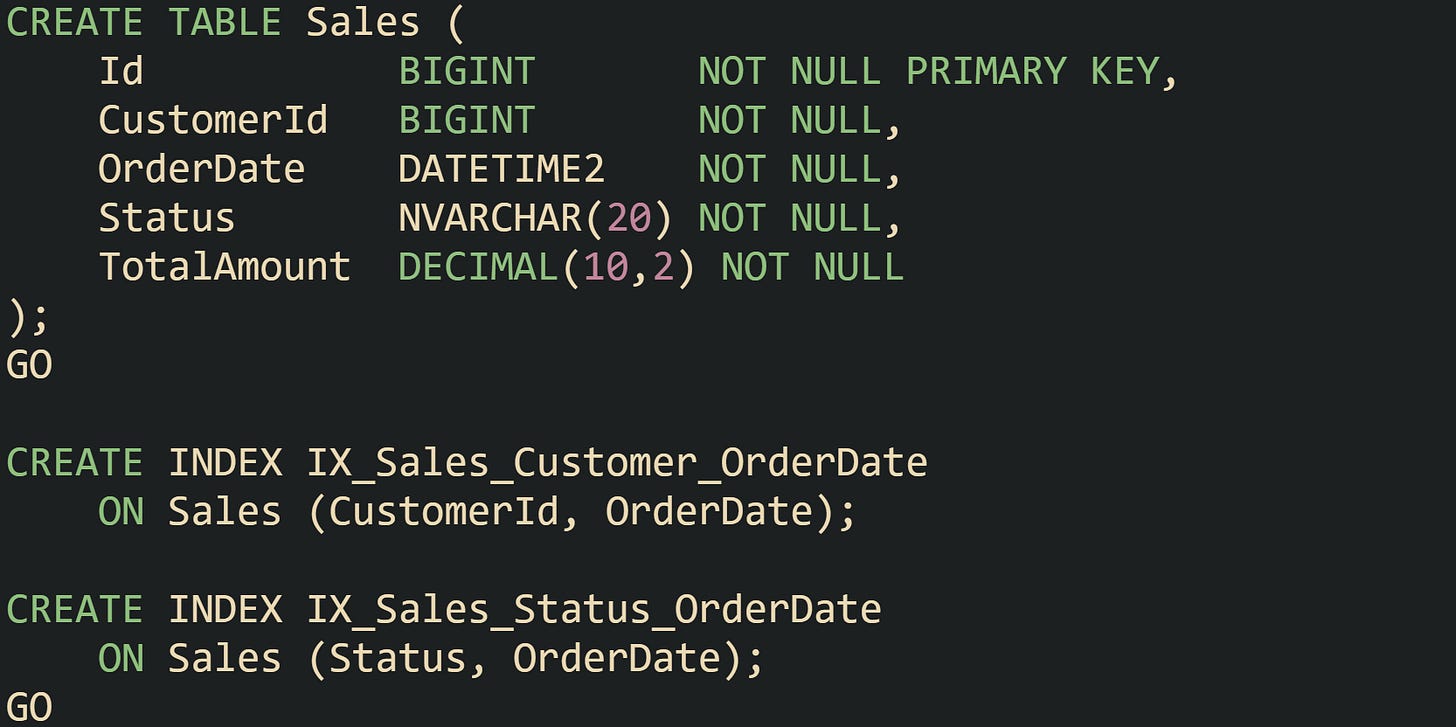

Take this Sales table in a transactional database that feeds dashboards and nightly reports:

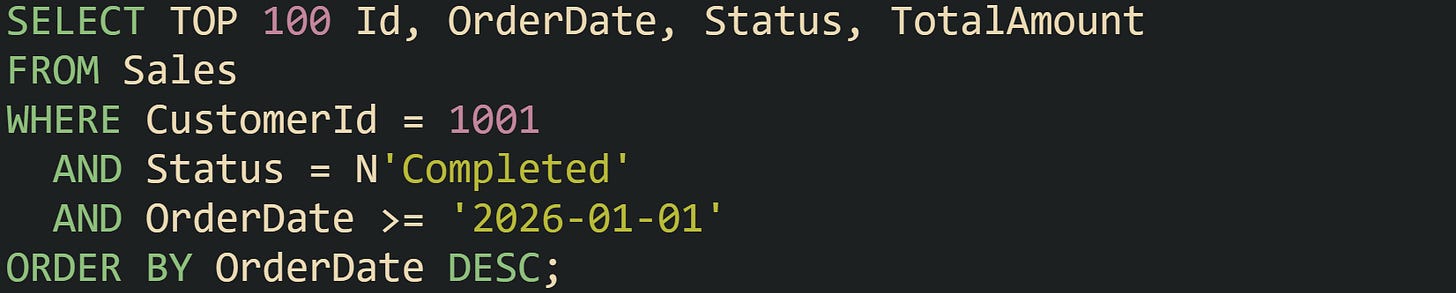

Reporting screens that show recent completed orders for one customer pull from this table with a query similar to the MySQL example but written in T SQL:

An estimated execution plan in SQL Server Management Studio can reveal that the optimizer chooses an index seek on IX_Sales_Status_OrderDate, applies a residual predicate on CustomerId, and performs key lookups into the clustered index to fetch TotalAmount. When nearly every row has Status = 'Completed', this plan ends up touching a large portion of the table, because the first predicate in the composite index is not selective for this workload.

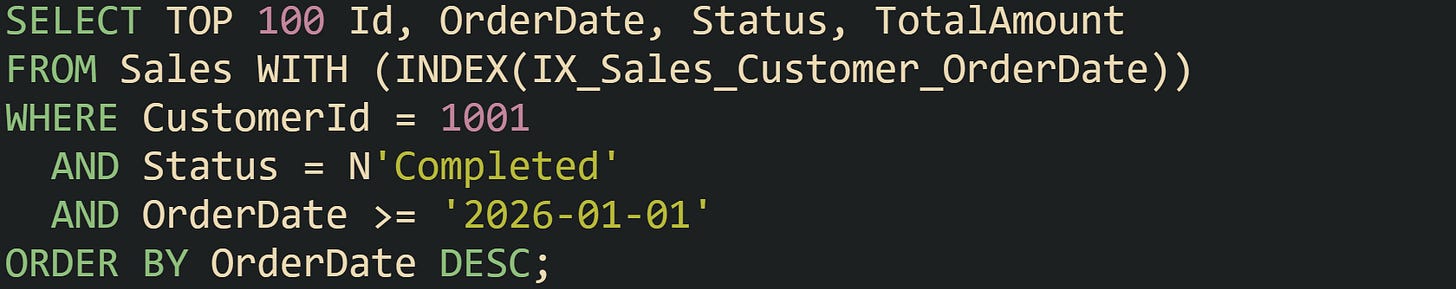

A table hint can steer the engine in a direction that fits the actual filter better. Placing an index hint right after the table name changes the planning step:

Execution plans generated from this text typically show an index seek on IX_Sales_Customer_OrderDate with a range on CustomerId and OrderDate, and then a predicate on Status applied to the index rows that pass the first filter. If the nonclustered index includes Status and TotalAmount as included columns, the engine can satisfy the entire query from the nonclustered index alone, without key lookups back to the clustered index.

On a medium sized table that holds millions of rows, that change can make a visible dent in query time, because the seek on a customer and date range greatly reduces the number of rows that participate in the plan. I O drops, and memory pressure from sorting or buffering rows falls as well, which benefits other queries that share the same instance.

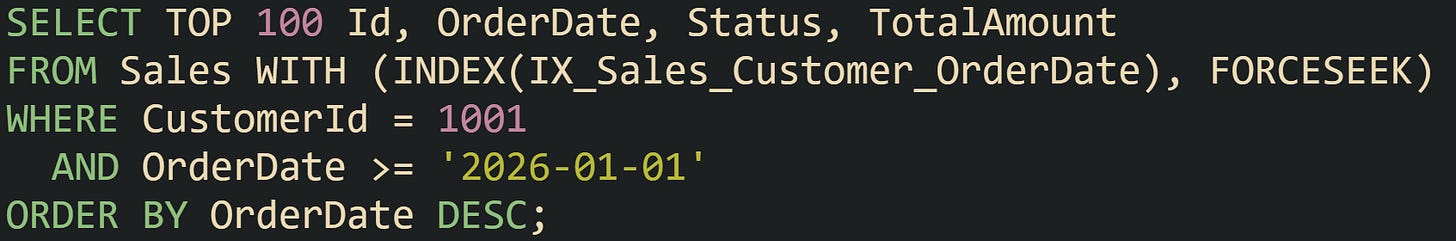

SQL Server also exposes a FORCESEEK hint, which gives a finer tool for encouraging index seeks instead of scans. When a table has a wide index that the optimizer occasionally scans in full, even though a seek would work, FORCESEEK can channel the engine toward the seek operator:

That form keeps the access path centered on IX_Sales_Customer_OrderDate and makes it far less likely that SQL Server will choose a scan on that index for this query. Combined with included columns that cover the select list, the plan can stay small and predictable, which helps when the same query text runs across many tenants or accounts with different data volumes but similar data shapes.

Conclusion

Index hints give you a direct way to influence how MySQL and SQL Server read tables by specifying which indexes the optimizer treats as entry points and how those choices interact with statistics and predicates. With the mechanics and examples in this article, you can map a slow query to its plan, see when the planner leans on a scan or a weak index, and then apply targeted hints or indexing and statistics changes that keep execution plans aligned with the filters and sort orders that matter for real workloads.