Interface Nil Checks in Go

A common area of confusion in Go comes from how interfaces behave with nil. Many developers expect an interface set to nil to act the same as a plain nil pointer, but that assumption doesn’t hold. The reason lies in the way Go stores both type and value information inside an interface.

Mechanics of Interface Nil Checks

Interfaces in Go are more than a placeholder for values. They keep track of two pieces of information at the same time: the type of the stored value and the value itself. This structure explains why comparing an interface to nil sometimes gives results that surprise developers. To see why, it helps to look at how the Go runtime arranges the pieces that make up an interface.

How Interfaces Are Stored in Memory

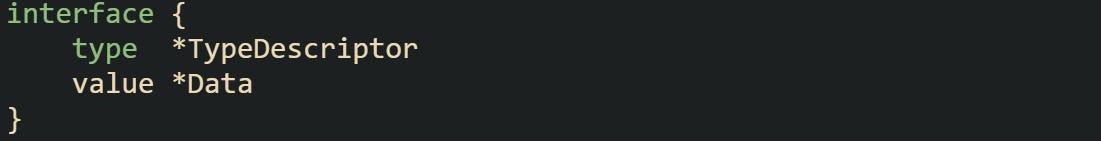

Internally, an interface has two fields. One is a reference to a type descriptor that tells the runtime what kind of value is inside. The other is a pointer to the actual data. Only when both are unset is the interface equal to nil. If the type descriptor has a value but the pointer does not, then the interface is still considered non-nil because it carries type information.

This can be pictured like a small structure, even though it’s hidden inside the runtime:

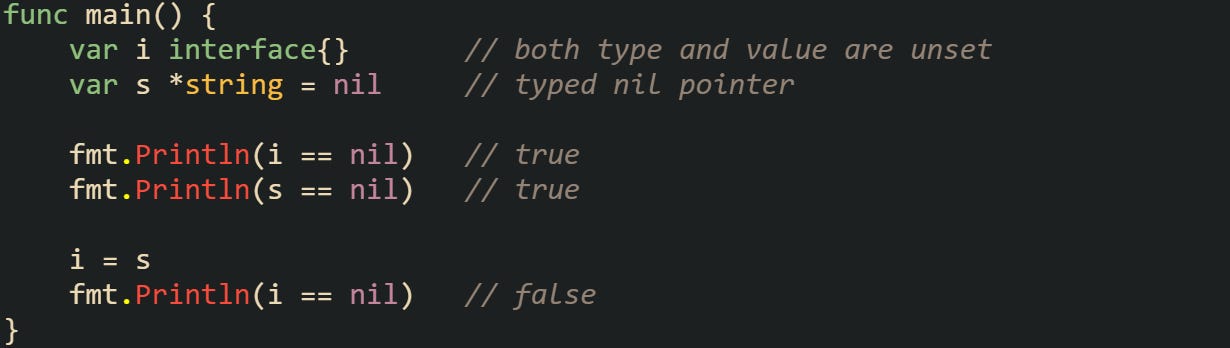

A quick test with code shows how this works:

The last print statement returns false because the type *string is stored in the interface even though the actual value is nil.

You can also print the type held inside the interface with %T to see what Go has stored.

The output confirms that i has a *string type attached. That type information is why the interface doesn’t behave like a plain nil.

Why Nil Inside an Interface Is Not Always Nil

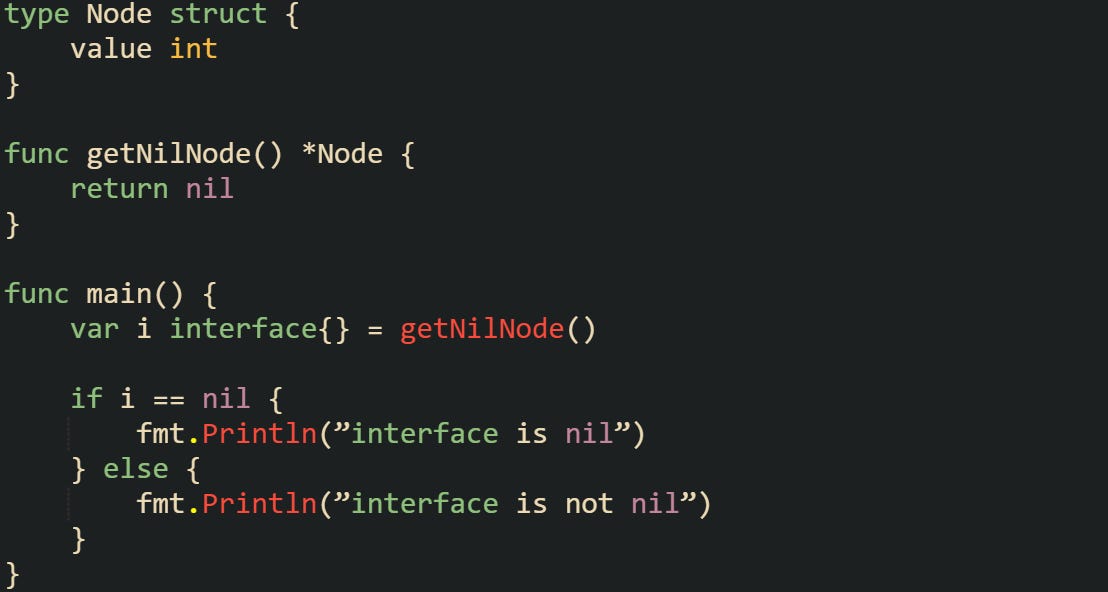

It’s common to store a typed nil inside an interface and then expect a comparison to succeed. Because the type is still attached, the interface won’t evaluate as nil. This is one of the main ways developers run into unexpected results.

This prints “interface is not nil.” The function handed back a nil pointer of type *Node, but the interface holds that type, so the check fails.

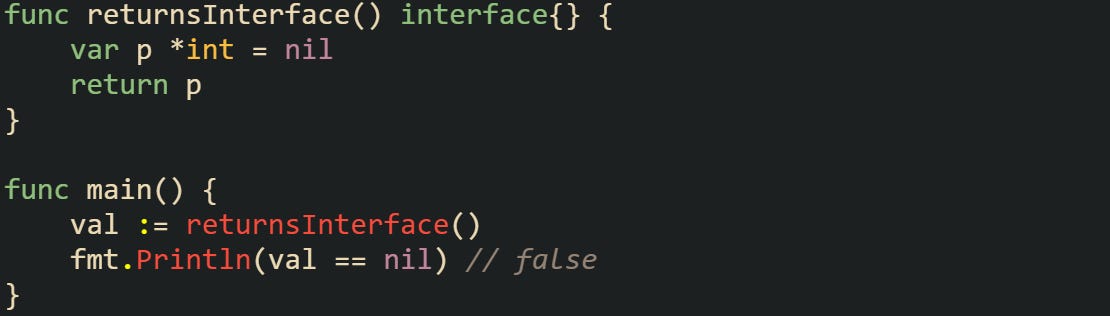

The same behavior appears when returning values that are expected to be interfaces. A function may return a nil pointer wrapped in an interface, and the caller won’t see it as empty.

The pointer itself is nil, yet the interface is not, because it still has type data for *int.

Proper Checks for Interface Nil

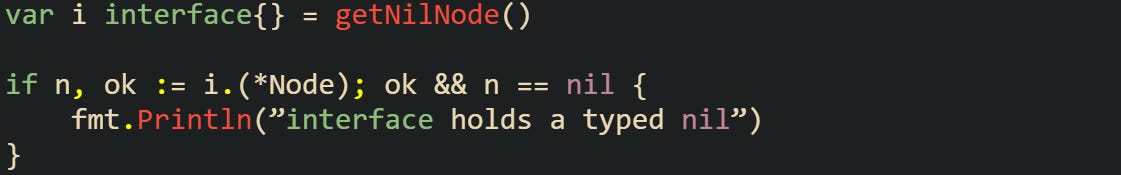

The safe way to handle this situation is to look inside the interface and compare the stored value directly. Type assertions are the most common tool for this. They let you grab the underlying value and then check it.

The type assertion confirms that the interface holds a *Node, and the check against nil verifies the pointer itself has no data.

Practical Cases of Nil Interfaces

The details of how interfaces hold type and value pairs become important in real projects. Developers don’t usually think about the runtime layout of interfaces while writing code, but these mechanics influence how checks against nil behave. A few common patterns make this behavior stand out, and they tend to appear in areas like error handling, assignments, and more advanced checking strategies.

Returning Errors

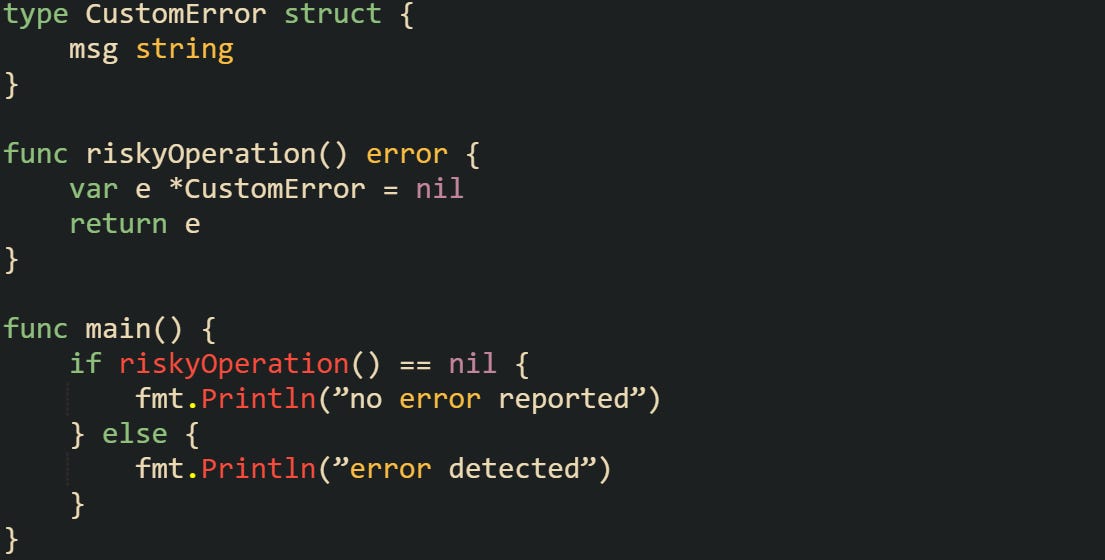

Errors are one of the most frequent use cases for interfaces in Go, and they’re also one of the most frequent sources of confusion with nil. The error type is an interface, so when a function returns a typed nil pointer as an error, the caller receives an interface that isn’t actually empty.

This prints “error detected” because the returned value still carries the type *CustomError. The interface has a non-empty type field, which means it’s not equal to nil.

It’s a subtle behavior that can make error handling unreliable if overlooked. To prevent it, functions should return a plain nil when no error occurs, instead of returning a typed nil pointer. A quick fix is simply returning nil directly rather than a typed variable set to nil.

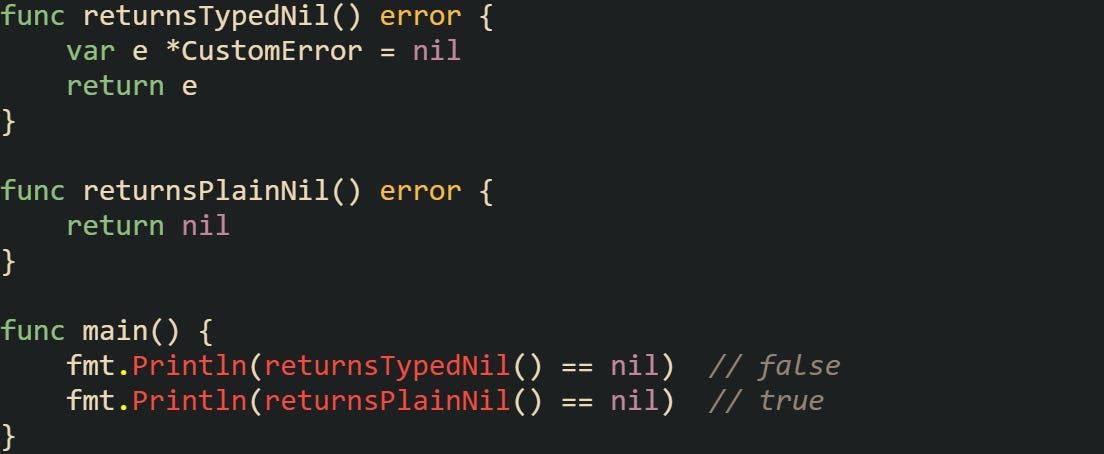

A second scenario can bring the point home by mixing typed and untyped returns:

Only the second comparison evaluates to true, because it returns a nil interface value.

Interface Assignments

Nil behavior can also trip up developers when assigning values into interfaces. Assigning a typed nil pointer into an empty interface leaves the type attached, which means the interface is not nil.

That single line is enough to puzzle someone new to Go. The type descriptor inside the interface is still *int, so the runtime treats it as non-nil.

Assignments with slices work the same way.

Even though s has no data and prints as [], the type information remains. The slice header inside the interface has a nil data pointer with zero length and capacity, and the interface still carries the []string type, so the interface value isn’t nil.

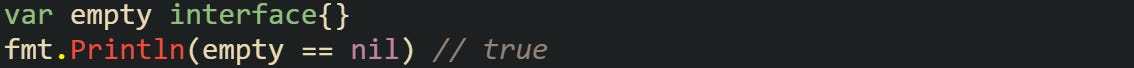

You can see the distinction more clearly by comparing to an empty interface variable that was never assigned:

Here, both type and value are unset, which is why the equality check works as expected.

Practical Check Pattern

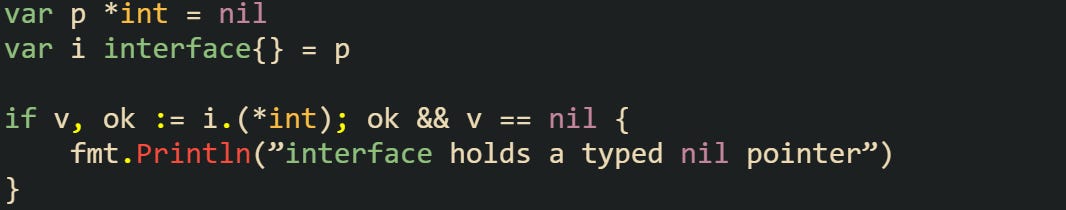

When writing code that deals with interfaces whose contents may be nil, it’s often safer to check the concrete value instead of the interface directly. Type assertions are the most common tool for this.

The type assertion unwraps the interface and makes the pointer check accurate. Without it, the direct i == nil comparison would fail.

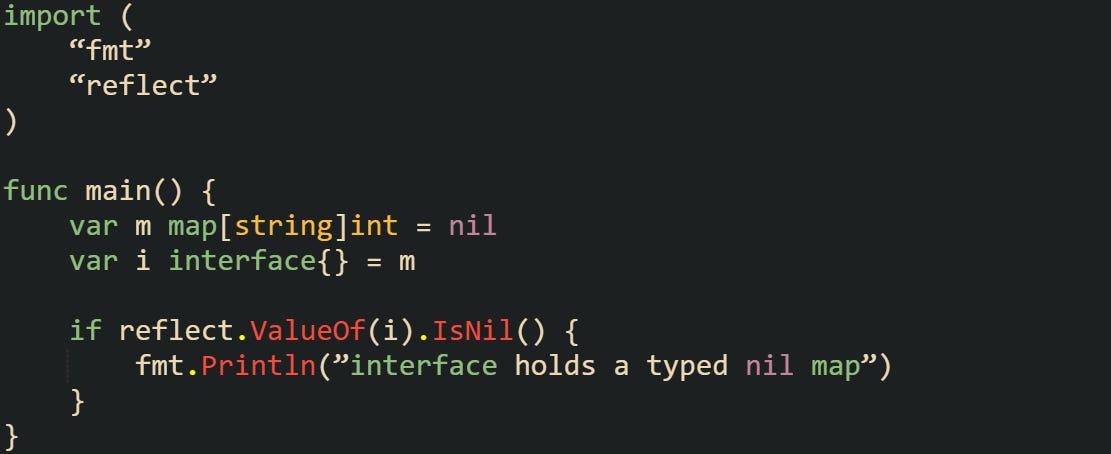

For generic checks where the type isn’t known ahead of time, reflection can help.

Reflection allows the runtime to confirm whether the stored value is nil, even if the exact type isn’t known when writing the code. This isn’t as fast as a type assertion, but it’s flexible for situations where the type can vary.

Conclusion

Interfaces in Go carry both type information and a value pointer, which is why a check against nil can behave in unexpected ways. When only the value is nil but the type is still attached, the interface won’t compare as empty. The safest way to handle these cases is to look at the underlying value through a type assertion or reflection, which makes it clear whether the interface is truly empty or holds a typed nil.