Java Scope, Part 4 — try-with-resources and Catch Blocks

Where scoped variables vanish after cleanup

This is part four in the series on Java scope. Part one took a quick look at how try and catch work with scope, but that was just the basics. This part gives them the space they need. try-with-resources, catch, and finally each create their own boundaries, and those rules can cause trouble if you’re not paying attention. They don’t act like regular blocks, and they clean up faster than most people expect.

I think this one matters a lot for beginners. You run into this kind of code everywhere, and the way scope works inside these blocks isn’t always obvious. Getting a feel for it early builds a foundation that makes the rest of Java a little easier to work with.

If you want to start from the beginning, here’s part one:

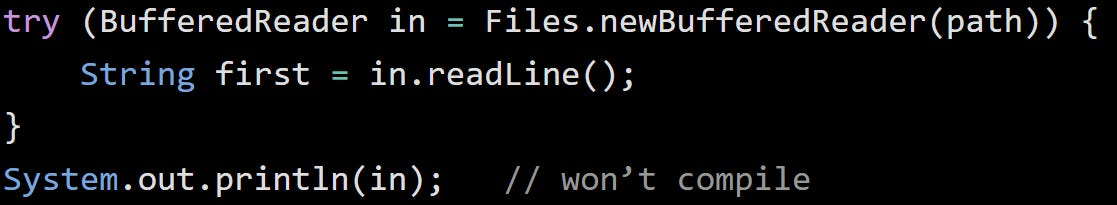

The Resource Header Is Its Own Bubble

Java treats the header of a try-with-resources block as its own small scope. Anything you declare there is closed and discarded as soon as the block finishes.

That variable only exists while the try block runs. After that, Java shuts it down and clears it out. You won’t be able to reach it in catch, finally, or anywhere outside that block. It's already gone.

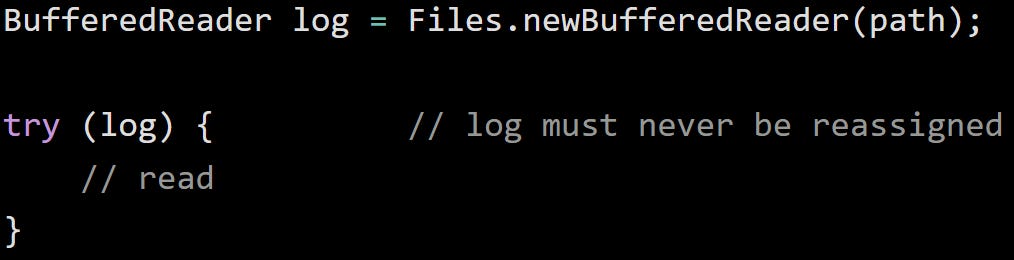

Java 9+ Lets You Reuse an Existing Variable (var needs Java 10)

Before Java 9, the only way to use the resource header was to create something new inside it. Now you can pass in a variable, but there’s a catch. It has to stay unchanged.

This works because log doesn’t get reassigned. The stream is closed at the end of the block, so while the variable is still in scope afterward, it now refers to a reader that’s already closed.

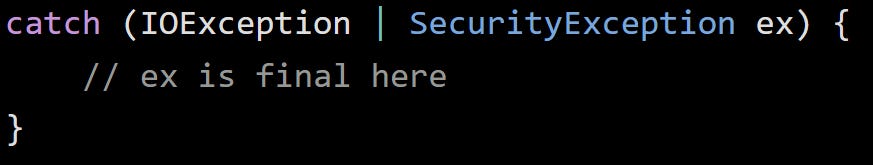

A Multi-Catch Parameter Is Frozen

You’ve probably seen catch blocks that handle more than one exception. When they do, Java gives you a shared variable, but it locks it down tight. That way, you don’t end up changing it and confusing what exception you’re actually dealing with.

You can’t assign a new value to ex, and that’s by design. It’s the same rule you ran into with lambdas back in Part 3. After Java picks a value for something like this, it expects it to stay put.

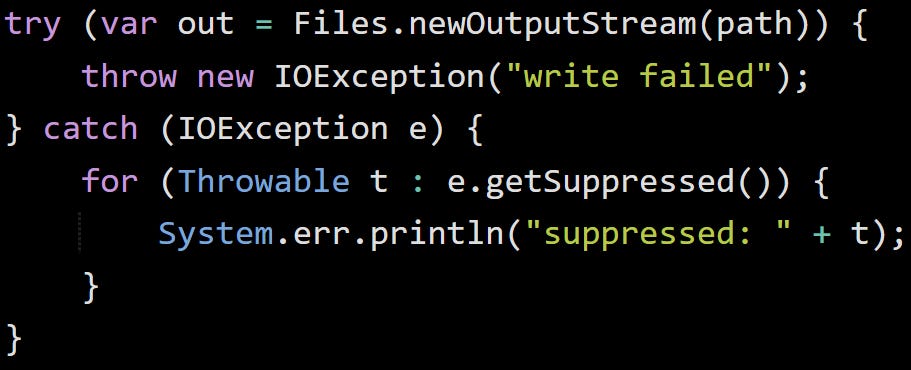

Suppressed Exceptions Still Show Up

This one took me a bit to appreciate. When something throws inside the try and then the cleanup code throws again, Java doesn’t throw away either one. It gives priority to the first, but it keeps the second hidden inside the first.

You don’t get direct scope access to both, but nothing’s lost. That second exception gets tucked away, and you can still pull it out during debugging. Java wants you to have the full story without needing extra tricks.

Quick Scope Reference for try, catch, and finally

When you declare a resource in the try header, it’s only around for the try block. You won’t be able to use it in catch or finally, and Java closes it for you right after that block runs.

Anything created inside the try body stays in that block too. The other sections don’t get to see it.

The exception parameter inside catch only exists while that block runs. It’s gone right after.

If you need something to last across all three blocks, declare it before the try. Part 1 already showed that trick with regular blocks, and it works the same way here.

Conclusion

Variables in the header or catch aren’t meant to last. Java cuts them off fast to keep the flow clean. If something disappears when you thought it’d still be there, chances are it was scoped too tight. These rules haven’t changed in years, but they still trip up code that tries to reuse a name or reach across blocks.

Next up is nested classes and anonymous types. They pull values from outer scopes in weird ways and don’t always follow the same pattern.