Working with text data inside a database means handling typos, spelling changes, or different ways of writing the same thing. Exact matches fall short when small mistakes appear, so fuzzy matching steps in to cover the gap. Major engines provide pattern functions or extensions for approximate matches. In PostgreSQL, ILIKE is a case-insensitive variant of LIKE. levenshtein is available in PostgreSQL through the fuzzystrmatch extension. MySQL and SQL Server include SOUNDEX natively, while PostgreSQL exposes soundex via fuzzystrmatch. Each one has its own mechanics that decide how values get compared and ranked.

How Fuzzy String Matching Works

Fuzzy string matching opens the door to comparing text values in ways that aren’t locked into perfect matches. Instead of treating two strings as completely different because a single letter is out of place, these functions create rules for similarity. Each one relies on its own background process, whether through phonetic codes, edit distance math, or flexible pattern matching.

Soundex Function

SOUNDEX dates back decades and was created to help match English names that sound alike. It’s built in on MySQL and SQL Server, and available on PostgreSQL through the fuzzystrmatch extension. The function works by breaking a word into its first letter and a sequence of numbers that represent groups of consonants. Vowels and certain consonants are ignored, leaving behind a sound-based code. Classic Soundex uses four characters. SQL Server returns four characters, MySQL’s SOUNDEX() can return a longer string unless you truncate it. Words that sound similar share the same code, which allows searches to pick them up together.

When you run it on names, it becomes obvious how it catches differences in spelling.

The result for both is R163. That’s why a search for one often returns the other.

Databases use this technique when phonetic similarity is more important than exact spelling. Imagine a directory where some users typed Smyth instead of Smith. With SOUNDEX, both would land in the same search results.

Queries like this can smooth over many real-world spelling quirks. The tradeoff is that it works best for longer words in English, so very short values or non-English names don’t always match as well.

Levenshtein Distance

In PostgreSQL, levenshtein is provided by the fuzzystrmatch extension, and it measures edits character by character. It measures how many edits it takes to turn one string into another. Edits can be substitutions, deletions, or insertions. That count of edits is the distance. A small distance means the two strings are close to each other, while a large distance means they’re further apart. In the background, the function uses a grid-based algorithm where each cell holds the number of edits required for matching parts of the two strings. The bottom-right cell of the grid tells you the total cost of converting one into the other. That’s why the method is widely used for spell-checkers and typo detection.

The query returns 3, because it takes three edits to go from kitten to sitting.

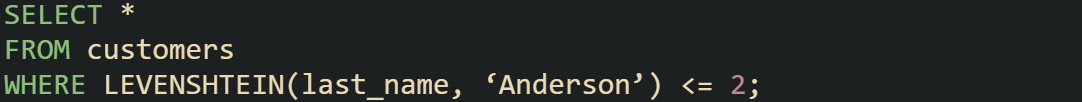

This also works in data queries when you want to allow some tolerance for errors.

This brings in names like Andersn or Andersen, which differ by only a couple of letters.

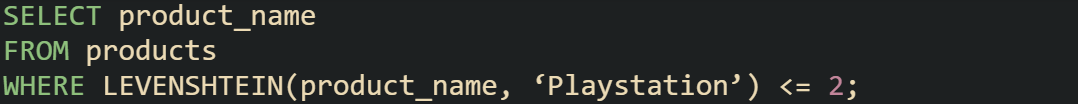

There are times when a second example helps illustrate the practical side.

Running this query can pick up values such as Plastation or Playstaton. It’s heavier to process than SOUNDEX, but it’s more flexible because it isn’t tied to English pronunciation.

ILIKE for Case Insensitive Patterns

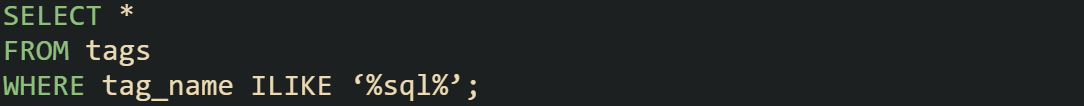

For PostgreSQL, ILIKE doesn’t calculate distances or phonetic codes, but it adds flexibility when case differences or partial matches are all you need. It works like the regular LIKE operator but removes case sensitivity, so “sql”, “SQL”, and “Sql” all match the same way.

That query finds any tag with “sql” inside, regardless of case. When combined with wildcards, it becomes a useful tool for broad searches where exact spelling isn’t always predictable.

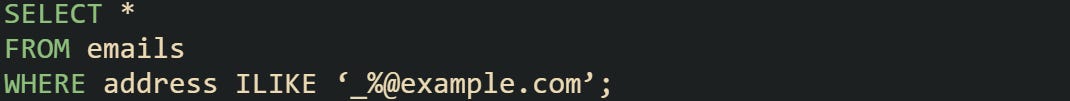

A slightly different use is catching pattern-based variations without case sensitivity:

This returns addresses ending with @example.com no matter how the letters are capitalized.

While ILIKE doesn’t judge closeness of spelling like SOUNDEX or Levenshtein, it fills an important gap by catching partial matches and dealing with the realities of human input where case differences are common.

Practical Tricks With Fuzzy Matching

Real value comes from applying these string functions to problems that show up in everyday data. Names, tags, and IDs all tend to carry inconsistencies that break exact comparisons. Instead of forcing strict matches, these tools provide a way to handle variations without losing useful records. Each type of data benefits from a slightly different method, whether that’s phonetic comparison, edit distance checks, or flexible pattern searches.

Matching Names

Names are among the most error-prone values in a database. Different spellings, typos, and regional variations all make matching tricky. SOUNDEX works well here because many differences are phonetic. Searching for “Catherine” should catch “Katherine,” while Levenshtein distance can fill in when the letters are misplaced rather than swapped for similar sounds.

That kind of query pulls in spellings that sound alike, giving wider coverage for real-world inputs.

When the problem is more about single-character mistakes, edit distance is better.

Small differences like “Hernandes” or “Hernadez” are picked up without treating entirely different names as matches.

Some systems combine these checks, where SOUNDEX reduces candidates to a smaller pool and Levenshtein then filters within that set. That way you can balance accuracy with performance.

Matching Tags or Labels

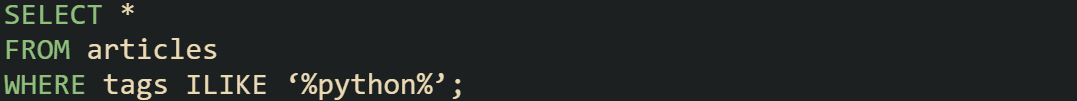

Tags are typically free-form text, so they vary in spelling, abbreviation, and casing. Pattern-based matching is practical here, since tags often include partial matches. ILIKE works well because it catches substrings regardless of case.

That query returns entries that contain the word “python” no matter how it was typed. It’s simple but effective when people don’t follow a strict tagging convention.

When spelling slips into the mix, edit distance helps cover typos.

Typos like postgressql or postresql still fall within range here.

A second example shows how tags with single words can also be matched with phonetic checks when spelling drifts in sound but not structure.

Even though SOUNDEX isn’t the strongest option for short words, it can sometimes catch edge cases where letters vary but the pronunciation is close.

Matching IDs With Typos

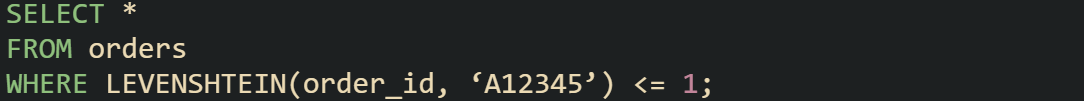

IDs may sound like they’d always be exact, but when people enter them manually, mistakes creep in. That’s where Levenshtein shines. An ID with one digit wrong or an extra character can still be matched against its intended value.

This covers a missing digit or a single transposed character without being too broad.

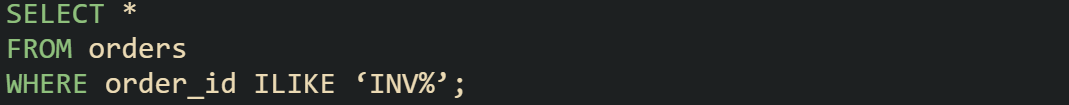

Another angle is when IDs carry a fixed prefix or suffix but the middle varies. Pattern searches can help check format before applying edit distance.

That pulls all invoices starting with INV, letting you run edit checks afterward only on relevant results instead of the entire table.

IDs don’t usually need phonetic checks, but combining prefix searches with Levenshtein gives a good safety net when data entry errors are likely.

Conclusion

String matching in databases becomes more flexible when mechanics like phonetic encoding, edit distance, and pattern checks come into play. SOUNDEX reduces words to sound-based codes, Levenshtein calculates the cost of edits between two strings, and ILIKE widens pattern searches without caring about case. Together they give queries a way to handle the small imperfections that real data always carries, letting searches work with how people actually type rather than only with exact equality.