It’s common to see matrix rotation come up in image handling, grid-based games, and many interview questions, where a two-dimensional array stands in for pixels or tiles on a board. Instead of building a second matrix every time the grid needs to turn, swaps in place can move values into their rotated positions and keep memory use flat. Thinking in terms of rows, columns, and index formulas makes the process mechanical and predictable, and careful ordering of assignments keeps every value safe while the matrix turns by ninety degrees.

Matrix Rotation Concepts

Dealing with rotations on a grid becomes much clearer when the matrix is treated as a set of integer coordinates instead of only as nested loops. Row and column indexes form a simple two dimensional coordinate system, and rotation can then be written as short algebra rules that move those coordinates around. Copy based rotation, where a second matrix holds the result, follows those rules directly, and later in place rotation uses the same rules while sending values around cycles inside the original array.

Coordinate System for Matrices

Java stores matrix data in a two dimensional array such as int[][] matrix. The first index is the row index and the second index is the column index. For a square n x n matrix, valid indexes for both dimensions run from 0 up to n - 1. Element matrix[r][c] sits in row r and column c, and the top-left position is matrix[0][0].

Rows are counted from top to bottom, and columns from left to right. That convention matches many grid based user interfaces, with the origin at the upper-left corner instead of at the center. Coordinate pair (0, 0) names the upper-left element, (0, 1) sits one step to the right, and (1, 0) sits one step down.

Take this code, it helps make that coordinate idea less abstract to see it in action:

Output from this code shows that row index 1 and column index 2 pick the number 6, which is the element in the middle of the second row. Reading matrix[r][c] as a coordinate pair instead of as a generic access into a two dimensional array keeps mental bookkeeping under control when rotation formulas are introduced.

Larger matrices sometimes need more structured logging. Small helpers that print coordinates along with values make that easier:

The method printWithCoordinates writes every (row, column) pair next to its value, which is handy when you rotate a matrix and want to confirm how positions moved by inspecting a before-and-after listing.

Square matrices are the natural fit for in place ninety degree rotation, because the grid keeps the same height and width after turning. Rectangular n x m matrices with n != m can still be rotated, but a ninety degree turn swaps dimensions, so the data no longer fits back into the original int[][] without new storage. Rotations discussed here focus on the square n x n case where matrix.length and matrix[0].length match.

Index Mapping for Ninety Degree Turns

Rotation by ninety degrees can be described entirely through index equations that accept an original coordinate (r, c) and produce a new coordinate (r', c'). The grid still uses index range 0 through n - 1 in both directions, so values never leave the matrix; they only move to new positions.

For a square matrix of size n, a ninety degree clockwise rotation sends (r, c) to (c, n - 1 - r). New row index is equal to the old column index, and the new column index is the old row index flipped around the right-hand edge of the grid. Ninety degree counterclockwise rotation sends (r, c) to (n - 1 - c, r), where the row index is flipped around the bottom edge and the column index keeps the original row. for example, a hundred eighty degree rotation uses (r, c) -> (n - 1 - r, n - 1 - c) and can be viewed as a double ninety degree turn.

Small coordinates help make these moves less abstract. With a 4 x 4 matrix, position (0, 1) under the clockwise mapping becomes (1, 3), because the new row is 1 and the new column is 4 - 1 - 0. Position (2, 0) moves to (0, 1) under the same mapping, because the new row becomes 0 and the new column is 4 - 1 - 2, which equals 1. Every coordinate pair has a unique destination, and no two pairs map to the same destination, so the rotation acts like a shuffle of the existing cells.

Those equations can be written directly into Java code that builds a rotated copy of a matrix. Copy based rotation keeps the original grid unchanged:

Here, the method rotateClockwiseCopy reads from matrix and writes into rotated, so there is no risk of overwriting data before it has been moved to its new home. That separation of source and destination is very friendly for reasoning about what happens during rotation.

Sometimes index mapping is easier to test and log as a separate utility, without touching the matrix at all. Using a compact helper works nicely for that kind of inspection:

mapClockwise packs the new coordinate into a small array. Small test harness code can loop over r and c, call mapClockwise(n, r, c), and print old and new coordinates side by side. That kind of logging confirms that top-left, top-right, bottom-left, bottom-right, and interior cells all move exactly where the formula predicts.

Layer Based In Place Rotation

Copy based rotation creates a fresh matrix and fills it with rotated values, which keeps the logic very direct but always allocates extra space. In place rotation takes the same index rules and applies them with swaps inside the original array, so only a small temporary variable is needed during each four way exchange. Thinking in terms of layers or rings around the center of the matrix gives a practical way to visit elements in a safe order and complete a ninety degree turn without losing any data.

Outer Ring Rotation Mechanics

Work on in place rotation usually starts with the outer ring of the matrix. For a square n x n grid, the outer ring consists of the top row, bottom row, left column, and right column. Those edges meet at four corners, and every element on that border participates in some four way swap when the matrix rotates.

Index arithmetic ties these moves into a single picture. For a clockwise turn, top edge values move to the right edge, right edge values move to the bottom edge, bottom edge values move to the left edge, and left edge values move back to the top edge. Rather than handle every position by hand, rotation groups positions into cycles. For layer index stored in first and its opposite side stored in last, the code visits all columns from first to last - 1 on the top edge and rotates one cycle at a time.

In this, rotateClockwiseInPlace walks layer by layer, where each layer narrows the focus toward the center. At a fixed layer, indexes first and last stay constant, so the inner loop only moves along the top edge of that ring. Variable offset measures how far along that top edge the code has moved, and that single number drives all four coordinates in the swap cycle.

Small matrices help make these swaps easier to see. Take a 4 x 4 grid with values 1 through 16 filled row by row. On the outer ring, an element in the top row at column index 0 trades places with values on the left, bottom, and right edges at positions that share the same cycle. As the inner loop increments i, those cycles slide along the ring until every border element has taken a turn.

Sometimes it helps to isolate just the outer ring and print it, to confirm which indexes belong to the current layer:

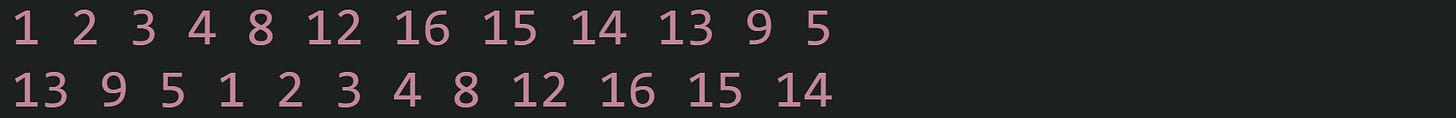

Call printOuterRing(matrix, 0) before and after rotateClockwiseInPlace(matrix) to see exactly which values sit on the outer ring and how they move during the rotation. With a 4 x 4 matrix filled row by row from 1 through 16, the console output from those two calls would look like:

Output from helper code like this makes the cycle based movement around the ring much easier to track.

Inner Layer Behavior In Square Matrices

Attention then moves inward. After the outer ring has rotated, the same logic applies to the inner rings. For an n x n matrix, layers are indexed from 0 at the border down to n / 2 - 1 at the deepest full ring when n is even. When n is odd, the layer loop still runs for n / 2 layers, and the single center element at index n / 2 in both directions stays in place during a ninety degree turn.

Work through specific sizes to see how layers stack. With n = 4, layer 0 uses first = 0 and last = 3, while layer 1 uses first = 1 and last = 2. That covers all positions, and no element belongs to two different rings. With n = 5, layer 0 covers the edges at indexes 0 and 4, layer 1 covers the edges at 1 and 3, and index (2, 2) is the center element that never moves.

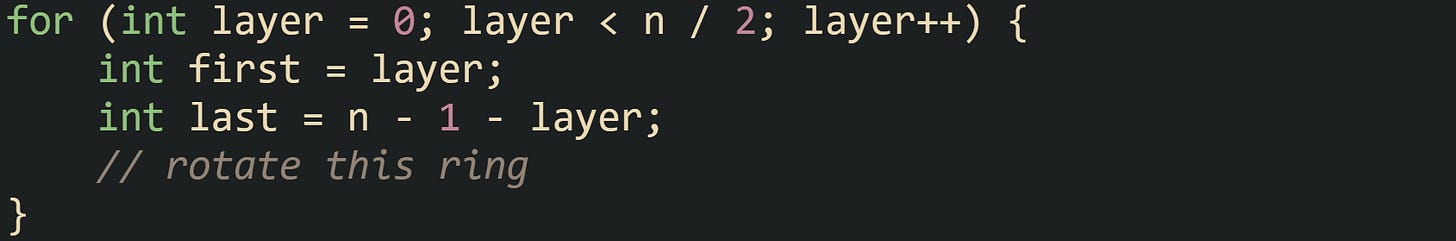

Code that rotates all layers does not need to know how many layers there are ahead of time, because the loop bound n / 2 handles both even and odd sizes.

That structure keeps outer rings and inner rings separate while still relying on the same swap logic. As layer increases, first moves downward and to the right, and last moves upward and to the left, shrinking the ring until there is nothing left to rotate.

Matrices in application code sometimes come from dynamic sources such as user input or data files, so row lengths are not guaranteed to match. Using a small check can verify that a matrix is square before rotation proceeds:

Calling checkSquareMatrix at the start of rotateClockwiseInPlace helps catch inconsistent row lengths early. Without this guard, index expressions like matrix[i][last] could throw an ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException halfway through a rotation, after the grid has already been partially modified.

Reasoning About In Place Swaps

Layer based rotation works because every four way swap matches the index mapping for a ninety degree turn. Four positions that lie on one cycle are chosen, and values are reassigned among them without needing a second matrix. All of the movement follows the mapping (r, c) -> (c, n - 1 - r) for the clockwise case.

Look at one cycle inside a fixed layer. Coordinate (first, i) sits on the top edge. Under clockwise rotation, this position maps to (i, last). In the code, matrix[i][last] = top assigns the saved value from the top edge into that destination. Next, the value at (last - offset, first) from the left edge moves into (first, i), which matches its mapped position on the top edge. The same idea applies to the bottom and right edges, until all four coordinates exchange values in a cycle.

Careful ordering avoids overwriting a value that will be needed later in the cycle. Temporary variable top holds the first value read, and the later assignment matrix[i][last] = top writes it only after the other three moves have taken place. Other three reads all pull from positions that have not yet been updated in that cycle, so no data is lost during the exchange.

Throughout the whole matrix, no two cycles intersect. Every combination of layer and inner index i picks one unique group of four coordinates. That guarantees that every element participates in exactly one swap cycle or stays fixed if it sits at the center of an odd sized matrix.

Similar construction can rotate the matrix counterclockwise. Swap order just changes to match the new mapping (r, c) -> (n - 1 - c, r):

In this code, rotateCounterclockwiseInPlace keeps the same layer structure, loop bounds, and offset arithmetic, but applies the index mapping in the opposite direction. Clockwise and counterclockwise variants therefore share the same mental model, with only the direction of travel around each ring changed by the order of assignments.

Conclusion

Matrix rotation in Java comes down to treating the grid as coordinates, applying the same small index mappings for ninety degree turns, and arranging swaps layer by layer so every four-way cycle moves values safely to new positions. Copy-based code keeps the mapping visible in a second matrix, while in place algorithms reuse the original int[][] storage with helpers like rotateClockwiseInPlace, ring walkers such as printOuterRing, and cycle logic that respects the square layout, so once you understand the mechanics, it becomes much easier to carry the same ideas into real image grids, board layouts, or other matrix-backed data.

![int[][] matrix = { { 1, 2, 3 }, { 4, 5, 6 }, { 7, 8, 9 } }; int value = matrix[1][2]; // row 1, column 2 System.out.println("matrix[1][2] = " + value); int[][] matrix = { { 1, 2, 3 }, { 4, 5, 6 }, { 7, 8, 9 } }; int value = matrix[1][2]; // row 1, column 2 System.out.println("matrix[1][2] = " + value);](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!cAMR!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F81829443-aaef-4931-ba0e-d7fbe6a83ce3_1660x446.png)

![public static void printWithCoordinates(int[][] matrix) { int n = matrix.length; for (int r = 0; r < n; r++) { for (int c = 0; c < matrix[r].length; c++) { System.out.print("(" + r + "," + c + ")=" + matrix[r][c] + " "); } System.out.println(); } } public static void printWithCoordinates(int[][] matrix) { int n = matrix.length; for (int r = 0; r < n; r++) { for (int c = 0; c < matrix[r].length; c++) { System.out.print("(" + r + "," + c + ")=" + matrix[r][c] + " "); } System.out.println(); } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!eWAL!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1753cee4-61e0-40fd-8de6-372eea1cca9a_1721x422.png)

![public static int[][] rotateClockwiseCopy(int[][] matrix) { int n = matrix.length; int[][] rotated = new int[n][n]; for (int r = 0; r < n; r++) { for (int c = 0; c < n; c++) { int newRow = c; int newCol = n - 1 - r; rotated[newRow][newCol] = matrix[r][c]; } } return rotated; } public static int[][] rotateClockwiseCopy(int[][] matrix) { int n = matrix.length; int[][] rotated = new int[n][n]; for (int r = 0; r < n; r++) { for (int c = 0; c < n; c++) { int newRow = c; int newCol = n - 1 - r; rotated[newRow][newCol] = matrix[r][c]; } } return rotated; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!VjIP!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff3c0c5f6-d02d-4957-a9f0-030d20a6f4cc_1662x786.png)

![public static int[] mapClockwise(int n, int r, int c) { int newRow = c; int newCol = n - 1 - r; return new int[] { newRow, newCol }; } public static int[] mapClockwise(int n, int r, int c) { int newRow = c; int newCol = n - 1 - r; return new int[] { newRow, newCol }; }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Rvqs!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9e4e9c3f-3b35-4a7a-848e-b45804c1424e_1690x280.png)

![public static void rotateClockwiseInPlace(int[][] matrix) { int n = matrix.length; for (int layer = 0; layer < n / 2; layer++) { int first = layer; int last = n - 1 - layer; for (int i = first; i < last; i++) { int offset = i - first; int top = matrix[first][i]; matrix[first][i] = matrix[last - offset][first]; matrix[last - offset][first] = matrix[last][last - offset]; matrix[last][last - offset] = matrix[i][last]; matrix[i][last] = top; } } } public static void rotateClockwiseInPlace(int[][] matrix) { int n = matrix.length; for (int layer = 0; layer < n / 2; layer++) { int first = layer; int last = n - 1 - layer; for (int i = first; i < last; i++) { int offset = i - first; int top = matrix[first][i]; matrix[first][i] = matrix[last - offset][first]; matrix[last - offset][first] = matrix[last][last - offset]; matrix[last][last - offset] = matrix[i][last]; matrix[i][last] = top; } } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!bglI!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F29ea3494-4e62-43d8-b1f8-80f0133f20c3_1797x773.png)

![public static void printOuterRing(int[][] matrix, int layer) { int n = matrix.length; int first = layer; int last = n - 1 - layer; for (int c = first; c <= last; c++) { System.out.print(matrix[first][c] + " "); } for (int r = first + 1; r <= last; r++) { System.out.print(matrix[r][last] + " "); } for (int c = last - 1; c >= first; c--) { System.out.print(matrix[last][c] + " "); } for (int r = last - 1; r > first; r--) { System.out.print(matrix[r][first] + " "); } System.out.println(); } public static void printOuterRing(int[][] matrix, int layer) { int n = matrix.length; int first = layer; int last = n - 1 - layer; for (int c = first; c <= last; c++) { System.out.print(matrix[first][c] + " "); } for (int r = first + 1; r <= last; r++) { System.out.print(matrix[r][last] + " "); } for (int c = last - 1; c >= first; c--) { System.out.print(matrix[last][c] + " "); } for (int r = last - 1; r > first; r--) { System.out.print(matrix[r][first] + " "); } System.out.println(); }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!BhTf!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F89f82612-e748-452f-970c-867413789f7a_1723x798.png)

![private static void checkSquareMatrix(int[][] matrix) { int n = matrix.length; for (int r = 0; r < n; r++) { if (matrix[r].length != n) { throw new IllegalArgumentException("Matrix must be square"); } } } private static void checkSquareMatrix(int[][] matrix) { int n = matrix.length; for (int r = 0; r < n; r++) { if (matrix[r].length != n) { throw new IllegalArgumentException("Matrix must be square"); } } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!CSFS!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F803b91e0-c458-428f-9cc1-54468ceede67_1713x334.png)

![public static void rotateCounterclockwiseInPlace(int[][] matrix) { int n = matrix.length; for (int layer = 0; layer < n / 2; layer++) { int first = layer; int last = n - 1 - layer; for (int i = first; i < last; i++) { int offset = i - first; int top = matrix[first][i]; matrix[first][i] = matrix[i][last]; matrix[i][last] = matrix[last][last - offset]; matrix[last][last - offset] = matrix[last - offset][first]; matrix[last - offset][first] = top; } } } public static void rotateCounterclockwiseInPlace(int[][] matrix) { int n = matrix.length; for (int layer = 0; layer < n / 2; layer++) { int first = layer; int last = n - 1 - layer; for (int i = first; i < last; i++) { int offset = i - first; int top = matrix[first][i]; matrix[first][i] = matrix[i][last]; matrix[i][last] = matrix[last][last - offset]; matrix[last][last - offset] = matrix[last - offset][first]; matrix[last - offset][first] = top; } } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!YurM!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc9a1a81e-db35-4be6-bd18-f5fa81dcda73_1774x769.png)