Ownership in Rust Structs and What Happens When You Move Data

How field-level ownership shapes what you can use and when

Working with structs in Rust means the compiler always keeps track of who owns what and when. If you’ve been using Rust for a bit, you’ve probably seen how variables get moved instead of copied. The same thing happens with structs and each field inside them. Build one, move it, or just move part of it, and the compiler watches what’s still safe to use and what’s no longer allowed.

How Structs Behave with Ownership Transfers

Ownership in Rust works the same whether you’re dealing with a simple value like an i32 or a more complex struct with multiple fields. But with structs, you're working with a group of values that follow different rules. Some get copied. Some get moved. The compiler handles it piece by piece and doesn't let anything slide. After a struct is created, what happens during a move depends entirely on the field types inside it. Rust checks everything clearly and upfront.

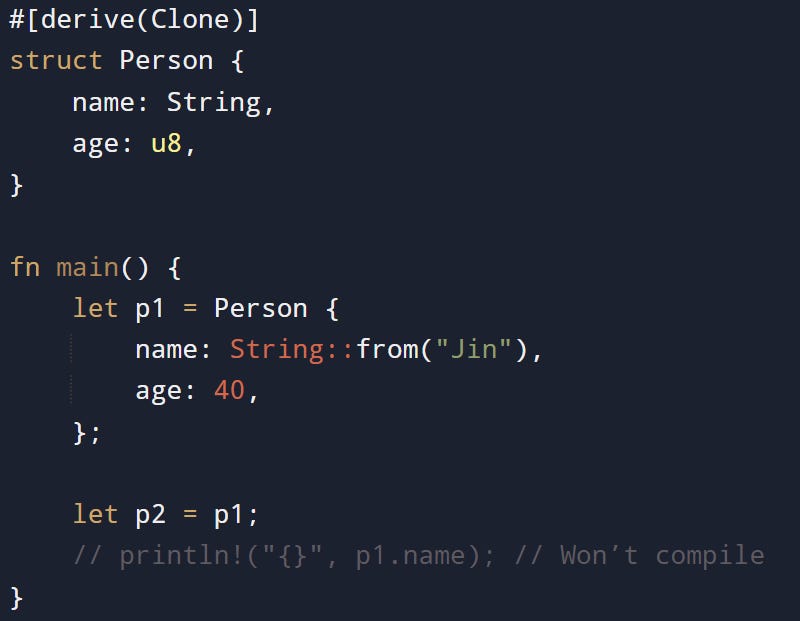

Creating Structs and Moving Entire Values

When you make a struct, Rust checks each field’s type and figures out how it should behave during a move. If it’s something that has Copy, like u32, then that value will be copied. But if it’s something like a String, which owns heap memory, then ownership is passed instead.

After p1 is moved into p2, you can’t use p1 anymore. The String field took ownership with it. Even though age is just a number and would normally be copied, Rust treats the whole struct as moved when one of its fields gets moved.

If you want to make a separate copy instead, you can use clone, but that only works if every field inside the struct also supports it.

Both name and age get cloned, and the original stays valid. That’s different from a move, which leaves the original in a state where it can’t be used anymore.

Behind the Scenes with Struct Moves

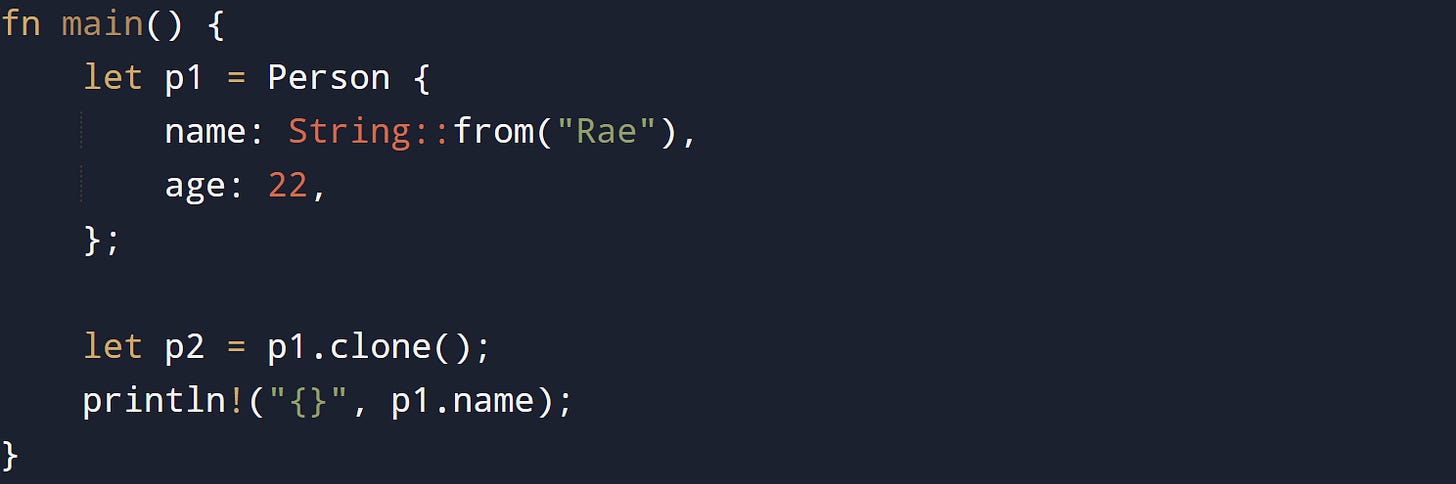

When you assign one struct to another, Rust works through each field one by one. Each part is either copied or moved depending on its type.

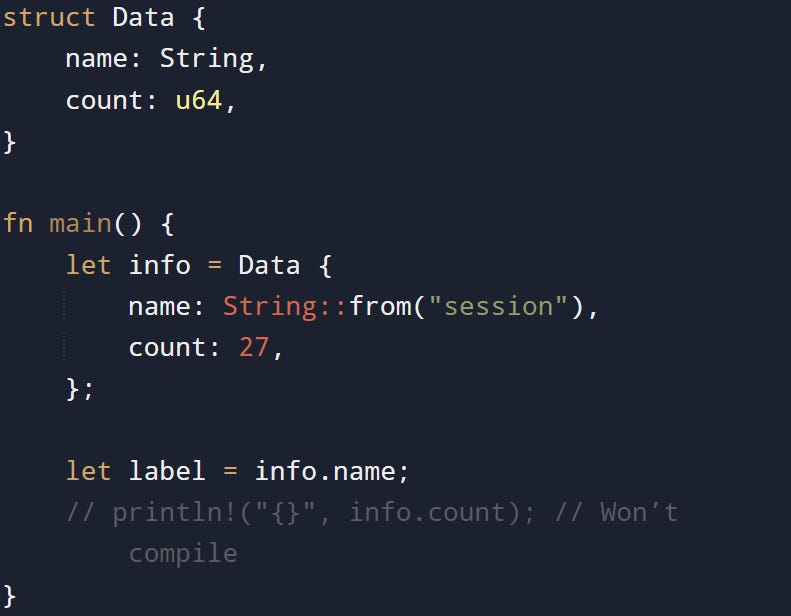

Take this struct:

And use it like this:

The id is copied, and the tag is moved. Rust breaks this down behind the scenes and handles both parts based on their types. There’s no mix-and-match at the code level. If you assign the whole struct, Rust decides what to move or copy for you.

You don’t get control over how each field is transferred during a full struct assignment. It always depends on what the field’s type supports.

What Rust Means by Move

A move doesn’t always mean data is being copied somewhere else. For types like String, Vec, and others that own heap memory, moving often just passes along a pointer and marks the old owner as invalid. That’s usually very fast. There’s no background memory sweep or duplication unless you ask for it.

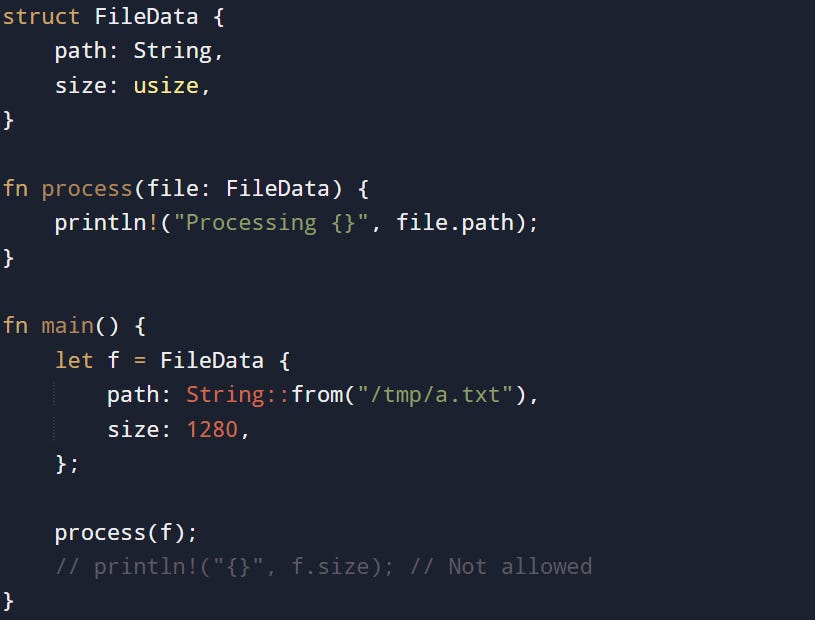

Here’s how this works in practice:

When you send f into the process function, ownership of the entire struct moves with it. That means the original variable can’t be used again after the call. Both path and size are now owned by the function.

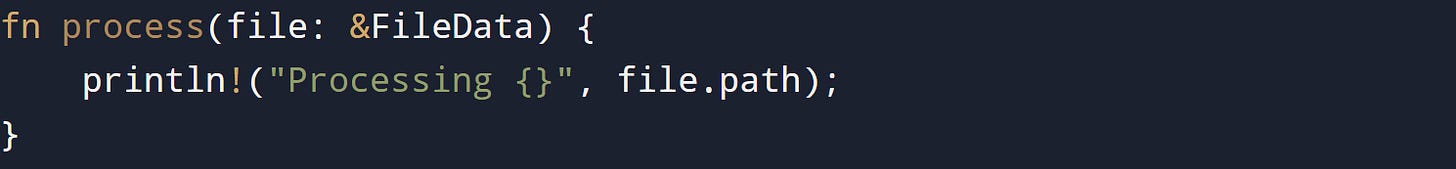

If you need to keep using the original struct, you can pass a reference instead:

This keeps the original value intact. You’re only borrowing it temporarily. No ownership is transferred, and nothing becomes invalid afterward.

Working with structs and ownership follows all the same rules as other types in Rust. The compiler keeps track of each field, and once something is moved, the original is no longer active. Every move is based on the type, and each struct field follows its own rules. Rust doesn’t cut corners on this, and that’s what keeps things consistent.

What Happens with Partial Moves and Field Access

Rust doesn’t treat a struct as a single thing once you start moving parts out of it. Each field can be handled separately, and the compiler tracks what’s still usable and what’s already been moved. This is where partial moves come in. If just one field gets moved out of a struct, the rest of it might still be there, but you won’t be allowed to use it in the same way anymore. The compiler steps in and blocks anything that could break the rules.

This can feel a little strict at first, especially if you’re coming from a language where you’re used to pulling values out of structs freely. But Rust tracks every move and makes sure nothing slips past it. You either keep ownership of the full struct, borrow from it safely, or move it in a way that’s clearly tracked.

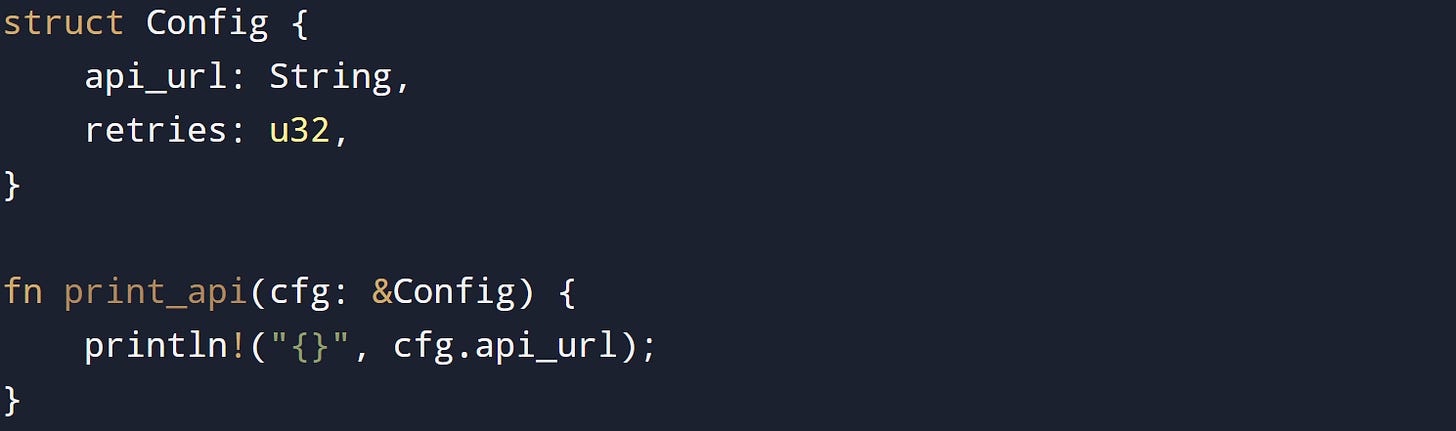

Borrowing Fields Without Moving

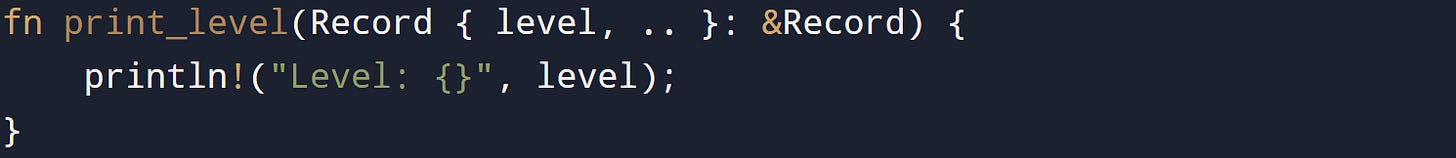

Borrowing lets you read or write to a field without giving up ownership. Because you’re only creating a reference, the compiler knows the original value still exists and isn’t being moved away.

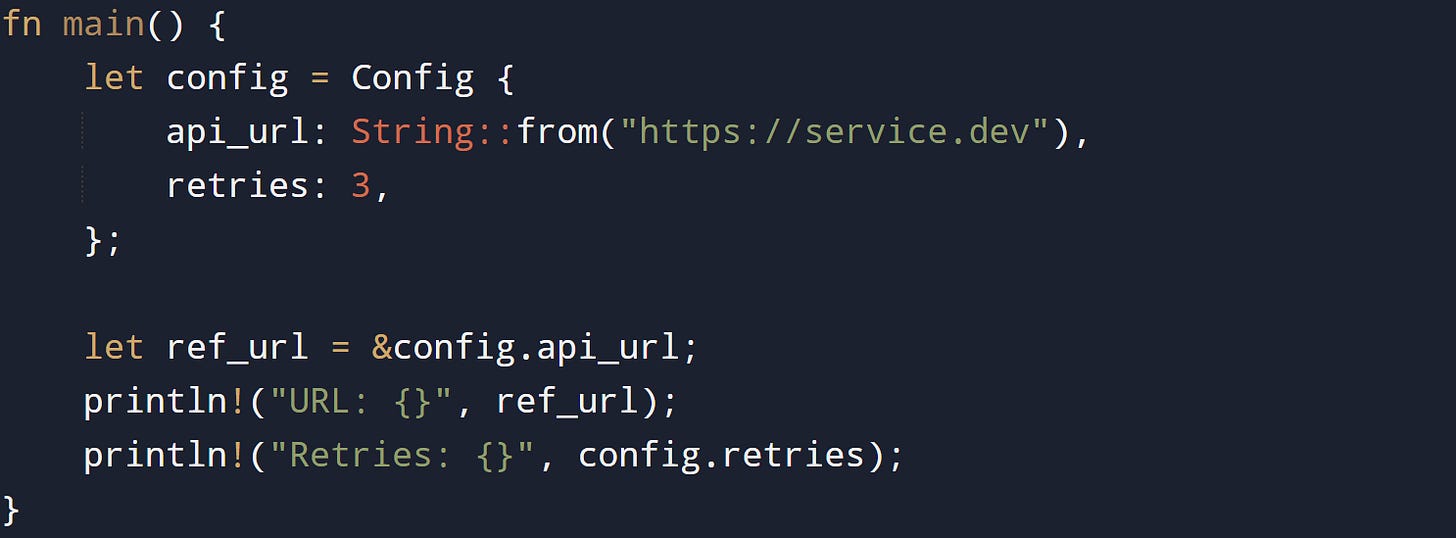

Above, you’re borrowing the full struct, not just one field. That keeps the ownership with the original caller, and the function can read from it without taking it. The same thing works if you borrow a single field:

The compiler allows this because ref_url is just a reference. No move has happened. The full struct is still in place and fully usable. This works well when you only need to peek at part of a value.

Moving a Single Field

The behavior changes as soon as you move a field that doesn’t implement Copy. If a struct has a String, and you move it out, then the whole struct becomes partially moved. That means you won’t be able to use the rest of the struct as a whole anymore.

The move here only affects name, but that’s enough to make info unusable. It’s not fully intact anymore, and Rust blocks anything that tries to access it as if it still were. This can happen even if the remaining fields are all simple values. The compiler doesn’t let you keep using a struct in a partially moved state.

Patterns That Move Fields

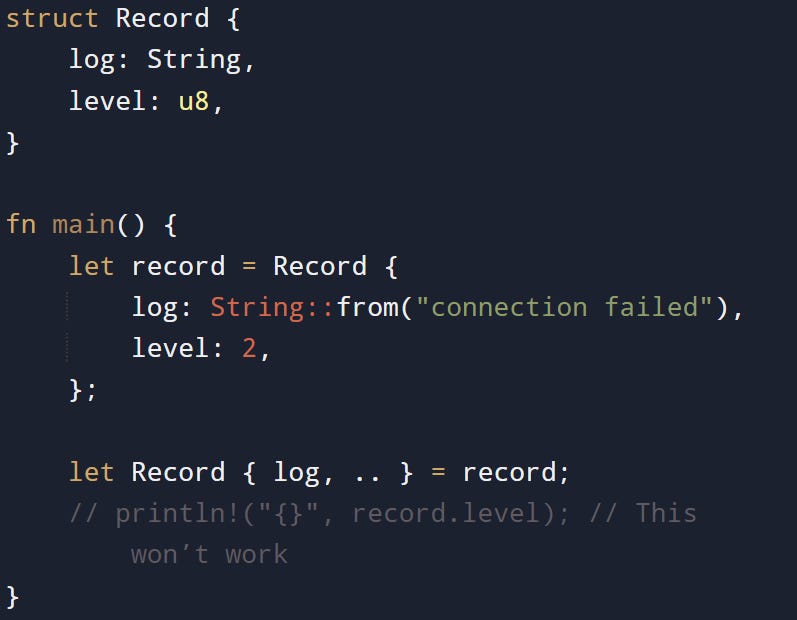

Moving can also happen through pattern matching or destructuring. If you pull out one field by name, Rust will treat that field as moved unless you borrow it or match by reference.

This move works the same way as a direct assignment. log is moved out of the struct, so the rest can’t be touched. If you need both fields, you either move them all at once or borrow instead:

Matching by reference is a safe way to use parts of a struct without taking ownership. You can still call functions like this without giving up anything.

Workarounds and Ways to Access Remaining Fields

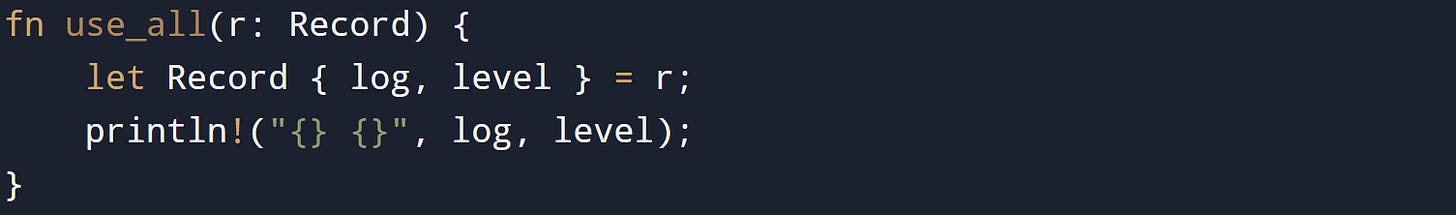

Sometimes you really do need to move part of a struct and still work with what’s left. There are a few ways to do that without running into problems. One option is to pass the full struct into a function that owns it. Then you can move all the parts at once, and there’s no partial move to worry about.

Everything is moved at the same time. There’s no need to block access because nothing is being left behind.

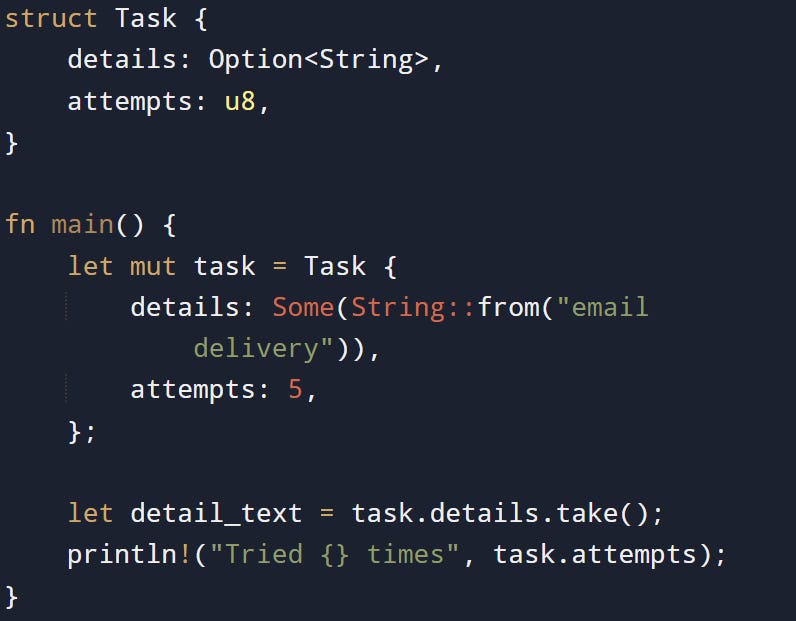

Another way is to wrap the field you plan to move in Option and then call .take() when you’re ready to move it. That swaps the value out and leaves None behind, which the struct can still hold.

This lets you move part of the struct without locking out the rest. Rust is okay with this because you’ve replaced the moved-out part with something valid. The struct is still in a usable state, and you’ve followed the rules without needing to clone or pass ownership around. With partial moves, the main thing to remember is that Rust won’t let you use a value that’s in an unclear or broken state. After a field is moved, the rest of the struct is fenced off unless you’ve borrowed the parts or moved all of them together. The compiler doesn’t guess. It checks each case, field by field.

Conclusion

Rust tracks ownership at every level, right down to each field in a struct. Move a value, and the compiler marks it gone. Borrow something, and it keeps everything in check. Each field either stays where it is or gets handed off, and the rules never change based on how big or small the struct is. This is what gives Rust its memory safety without a runtime system watching over it. The compiler does the work early and makes sure nothing slips through.