Go doesn’t jump straight into main first thing. Before that function is touched, the runtime goes through every imported package, sets up their variables, and runs any init functions they define. The order comes from the import dependency graph, not the textual order of import statements. Seeing how this process works makes it clear why certain values are already prepared when main begins and why the sequence of imports matters for how code runs.

Package Initialization in Go

Every Go package goes through a preparation stage before it’s used anywhere in a program. This stage is automatic and handled by the runtime without any developer intervention. It involves evaluating all top-level variable declarations and then running any init functions that are defined. By the time another package or main refers to it, that package is guaranteed to be fully initialized.

This process has a few rules that shape the exact sequence. Variable declarations run first, followed by one or more init functions in the same package. Within a single package, that order never changes, which makes it easier to reason about how values are set before they’re used.

Package-level Variables

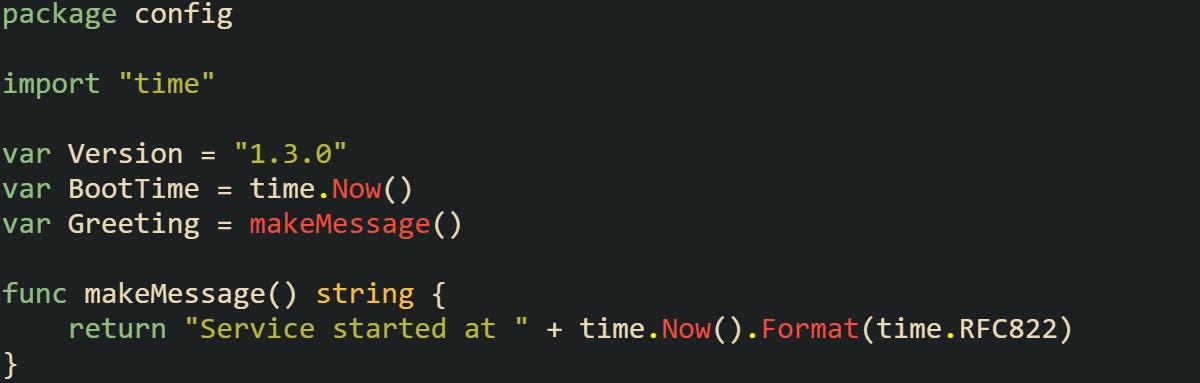

Top-level variables in Go are assigned before any other code in a package runs. These variables can hold static values, but they can also be the result of function calls or expressions. That makes them more than placeholders, because initialization can carry logic with it.

When this package is imported, Version gets its string value immediately, BootTime captures the moment of initialization, and Greeting is filled in by calling makeMessage. None of this requires main or any other function to run; it all happens as part of the package’s preparation.

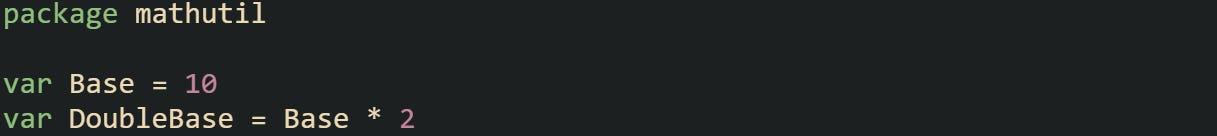

Package-level variables are initialized by dependency order. If a variable’s init expression depends on another, the dependency is initialized first. When there’s no dependency, declaration order applies. You can reference a package variable declared later, as long as there’s no cycle.

DoubleBase here will always come out as 20 because Base is set first.

The Init Function

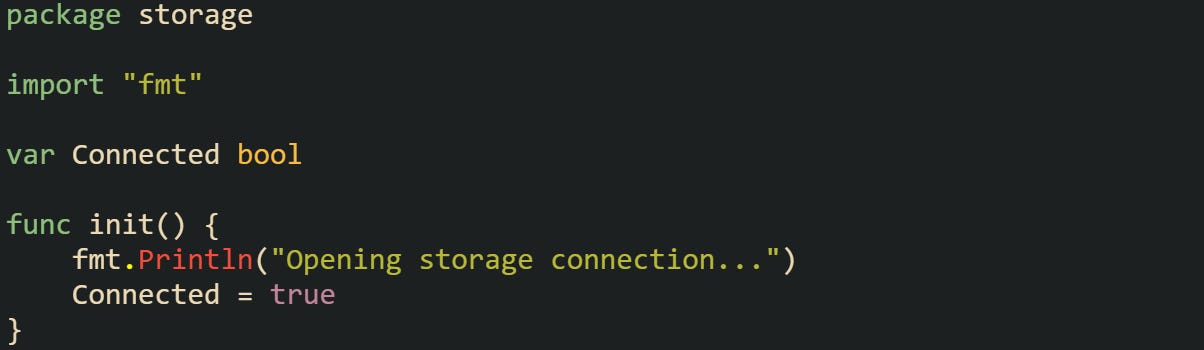

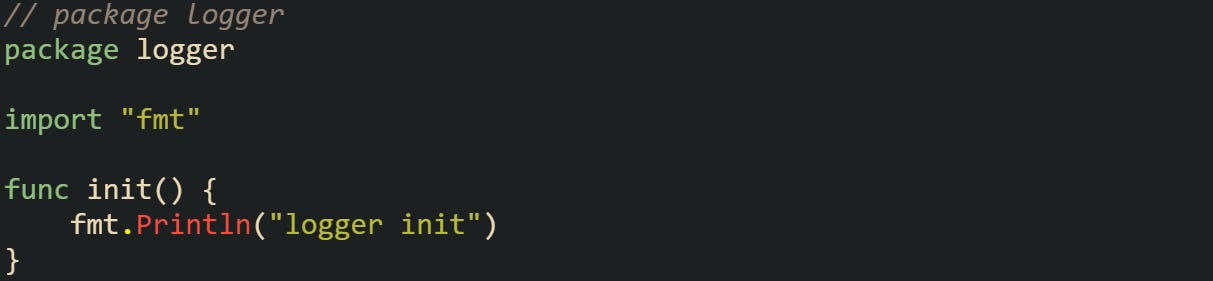

Variables alone often aren’t enough when a package needs to perform setup steps. That’s where the init function comes into play. It’s a special function that requires no signature, doesn’t return anything, and is triggered automatically.

When storage is imported, Go first sets Connected to its zero value (false), then runs the init function. Inside that function, Connected is updated to true, and the message prints to standard output. By the time the package is ready for use, it has already simulated a connection being opened.

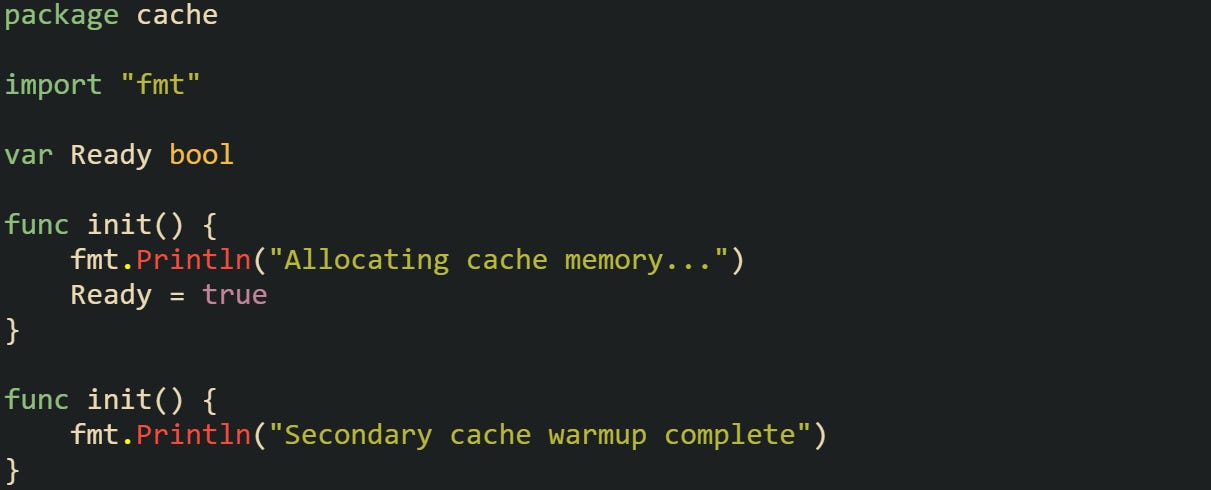

Packages aren’t limited to a single init. If multiple are declared across files in the same package, Go runs all of them. The sequence within each file still respects the rule, variables first, then init functions in order of appearance.

Both functions execute, one after the other, before anything else calls into cache. This makes init useful for performing one-time actions that prepare a package for use.

Order Inside a Single Package

Within a package, Go initializes package-level variables stepwise in dependency order, picking the earliest declaration that doesn’t depend on an uninitialized variable. After all variables are done, it runs all init functions in the order they appear in the source. This rule prevents a scenario where an init function runs before its supporting variables are ready. It also creates a predictable structure for developers, since you don’t have to guess what will be set first.

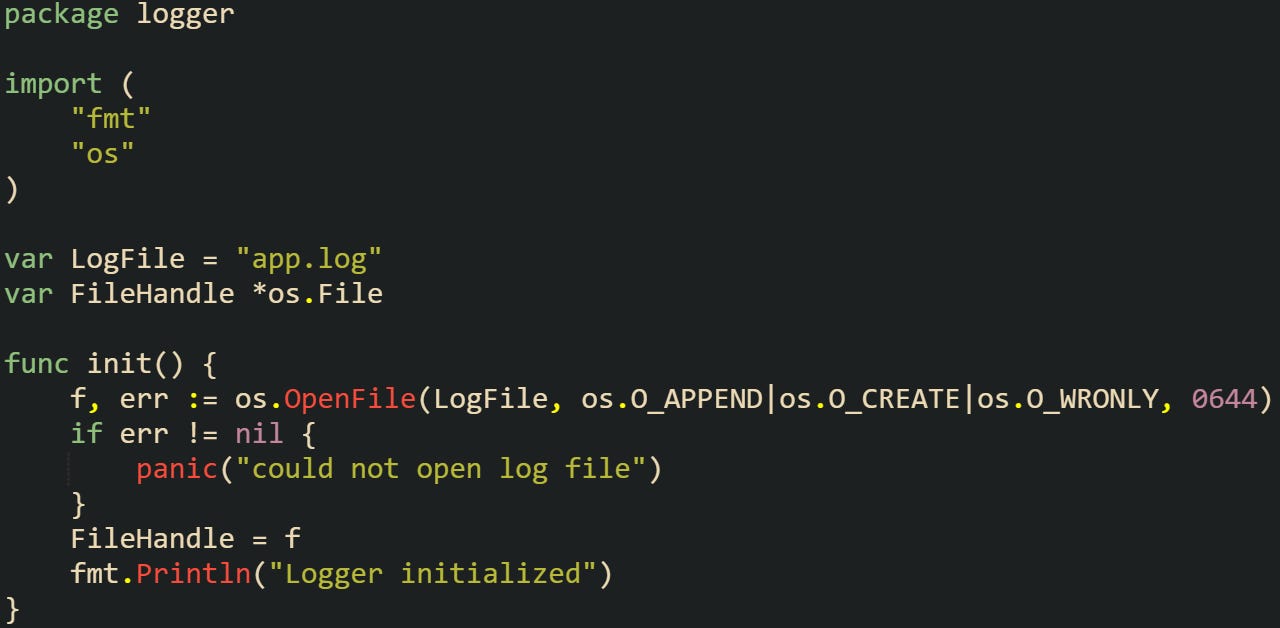

In the code above, LogFile is set first. Then, inside the init function, LogFile is already available to be passed into os.OpenFile. If Go reversed the order, this code wouldn’t work as expected. For more complex cases, a package can have several variables and multiple init functions. All package variables are set first. Then init functions run in lexical file-name order, and within each file in source order.

Import Order and Execution Flow

A Go program prepares packages by walking the import dependency graph. A package only initializes after its dependencies finish, which means their variables and init functions are ready first. This design gives Go a consistent way of preparing the entire dependency graph so that everything is in a ready state before main ever runs.

Dependency-driven Imports

Every import in Go carries weight because it dictates when a package will be set up. If package A imports package B, then B must be fully initialized before A. This rule applies recursively, so a chain of imports is followed to the deepest dependency before anything higher up begins.

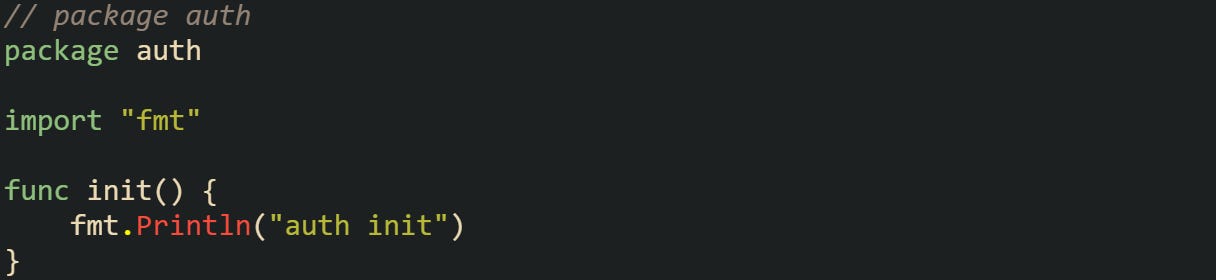

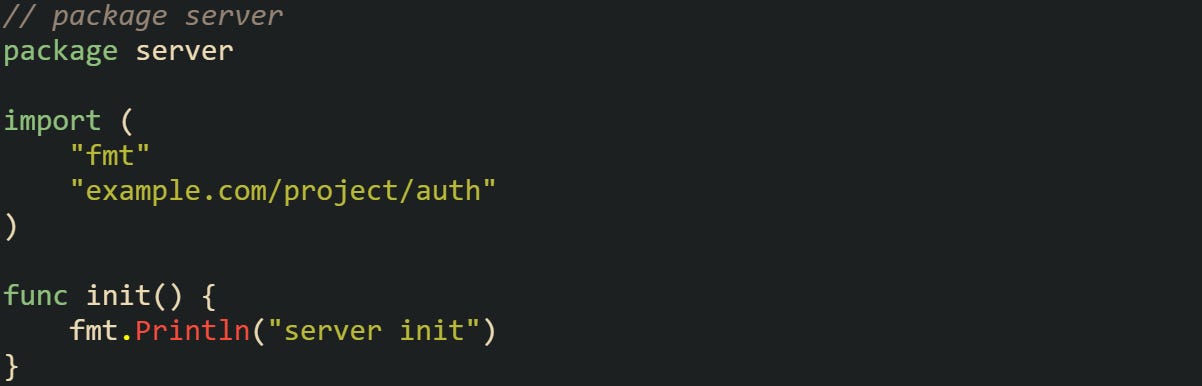

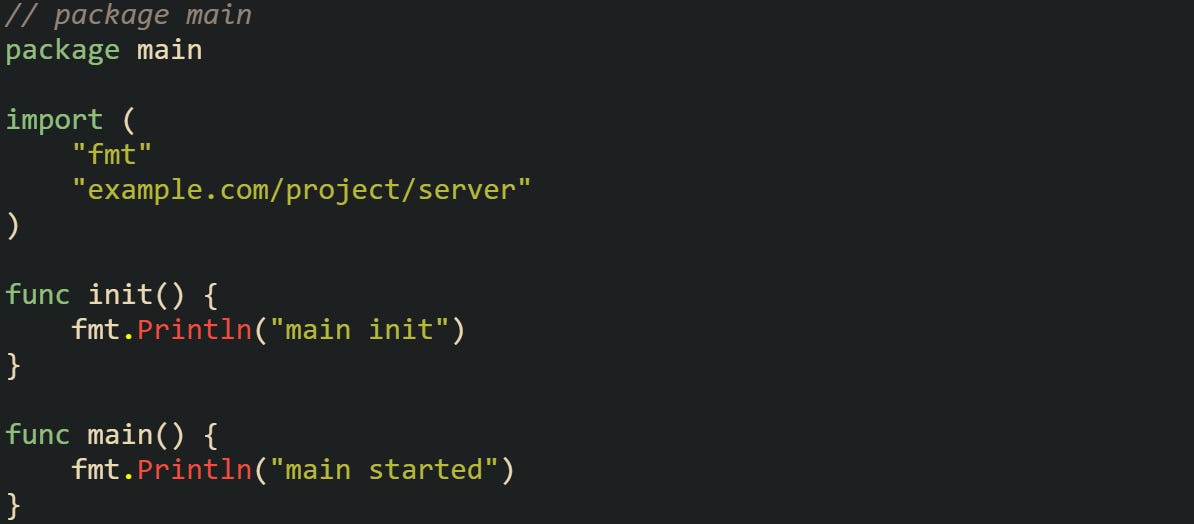

Running this sequence produces output in the order of dependency: first auth, then server, then main. This pattern holds across any chain of imports, no matter how many layers deep it goes.

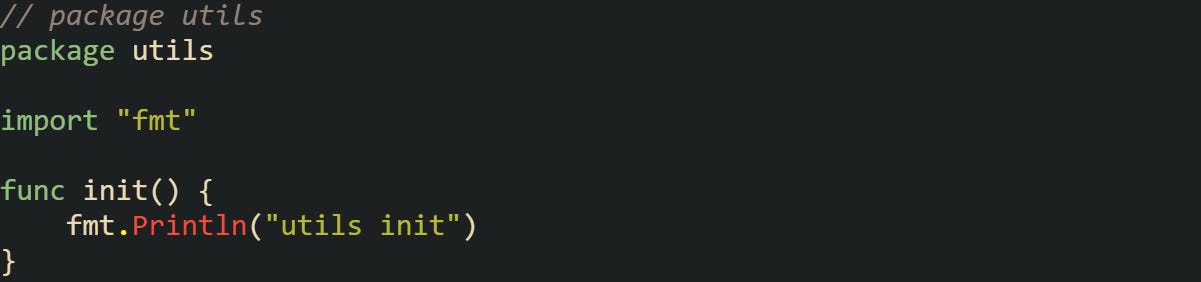

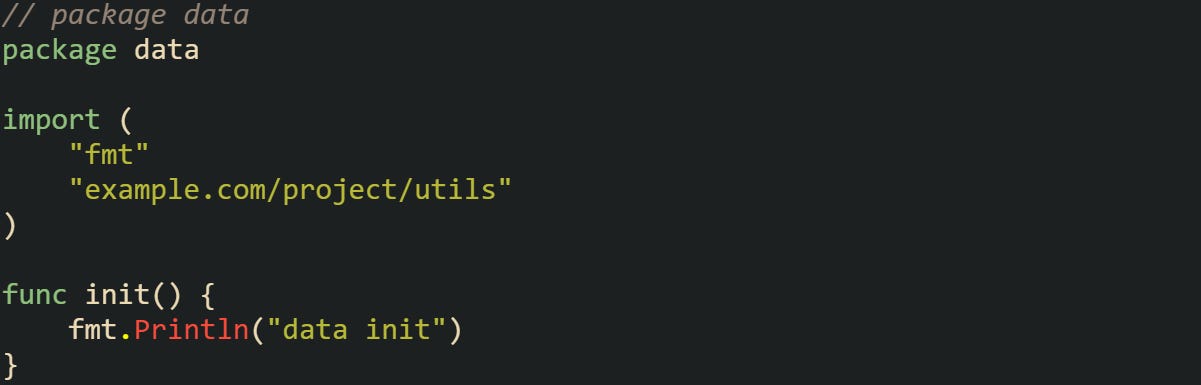

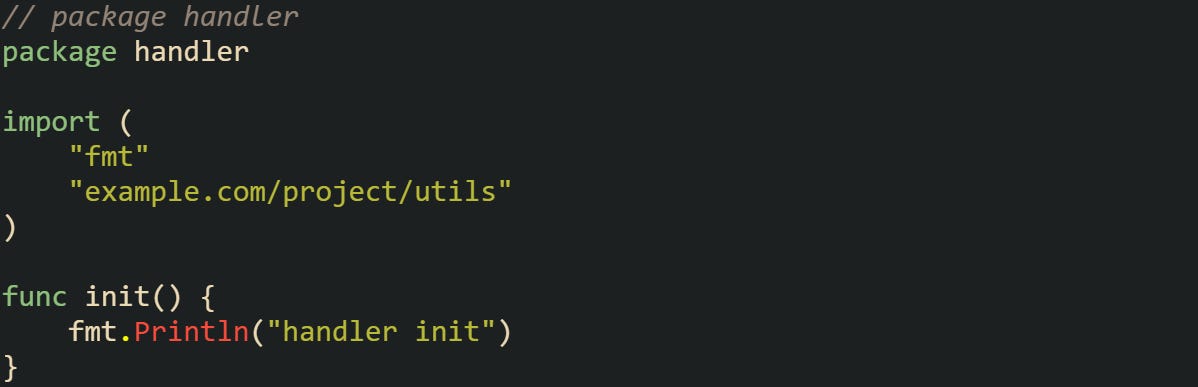

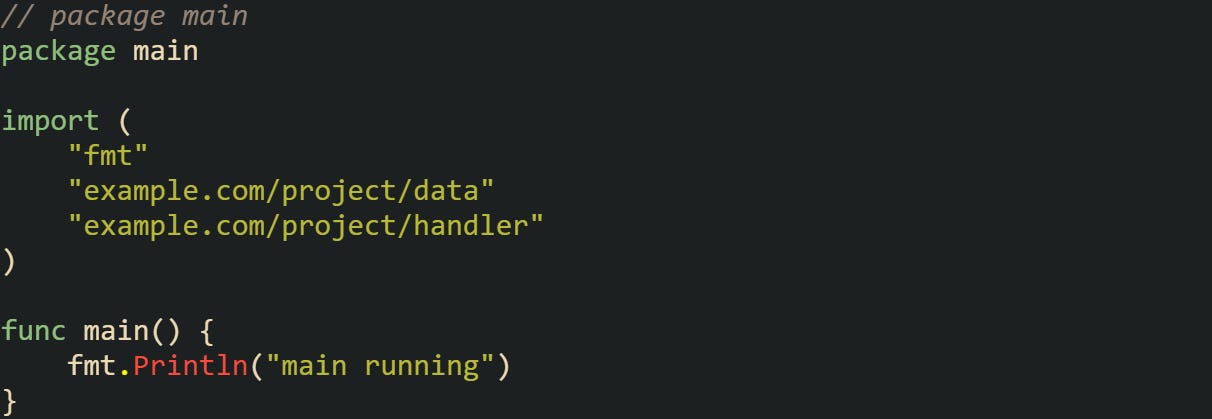

Import Graph

Go resolves imports by building a graph of all dependencies. Each node is a package, and edges represent their import relationships. Packages initialize in dependency order, and a package only starts after its imports are finished. If more than one package is ready at the same time, the spec applies a clear rule: the first uninitialized package in the list of all packages sorted by import path is chosen. Initialization happens in a single goroutine, one package at a time, and every package is initialized just once.

The import graph shows main depending on both data and handler, and both of those depend on utils. Go resolves this by running utils first, then data and handler in turn, and finally main.

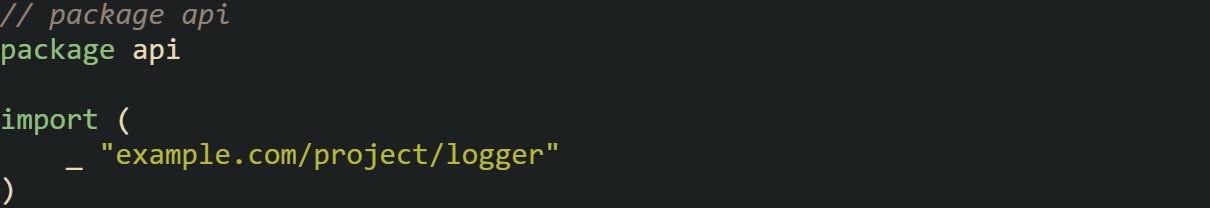

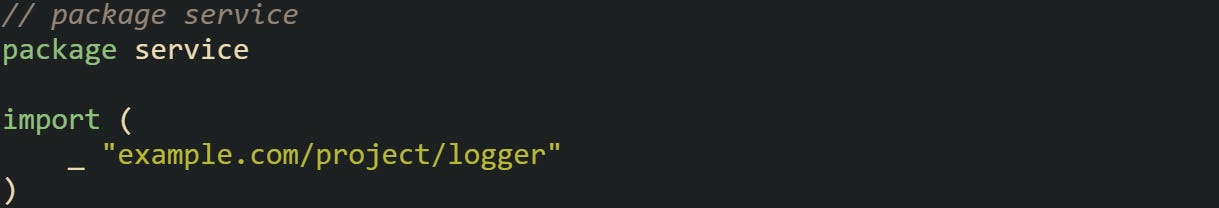

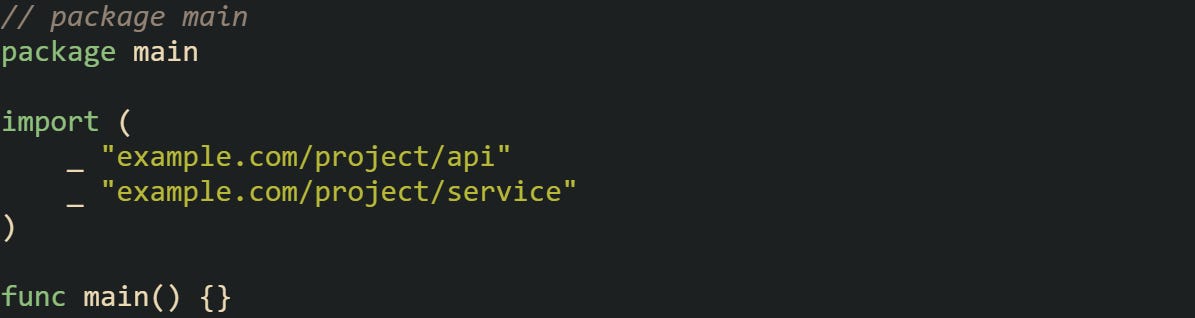

Multiple Imports of the Same Package

Go doesn’t re-run initialization if a package is imported in more than one place. It executes all top-level assignments and init functions only the first time, then shares that result with every package that depends on it. This avoids duplication and prevents initialization code from running multiple times in unpredictable ways.

logger is imported both through api and service, but its initialization runs just once. This prevents duplicated messages or duplicated setup, and it guarantees predictable behavior across the import chain.

Blank Imports

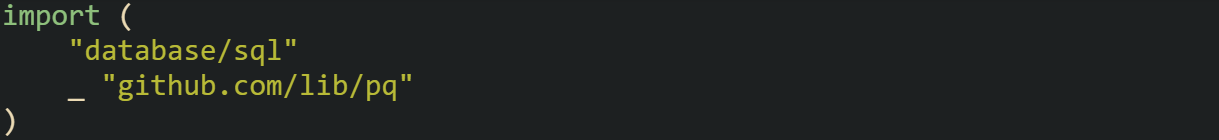

There are situations where you want a package to initialize but don’t need its exported functions or variables. Go supports this through blank imports, written as _ "package". This pattern is common for packages that register themselves with a framework or library during their init step.

One of the most visible cases is database drivers in database/sql.

The pq driver initializes and registers itself with sql, even though no symbols are referenced directly in code. The blank identifier _ tells the compiler that the import is intentional and needed for side effects, but unused otherwise.

Blank imports aren’t limited to drivers. They can be used to pull in monitoring libraries, feature toggles, or anything else that performs setup work entirely in init without needing to expose functions or types.

Example of Order Across Packages

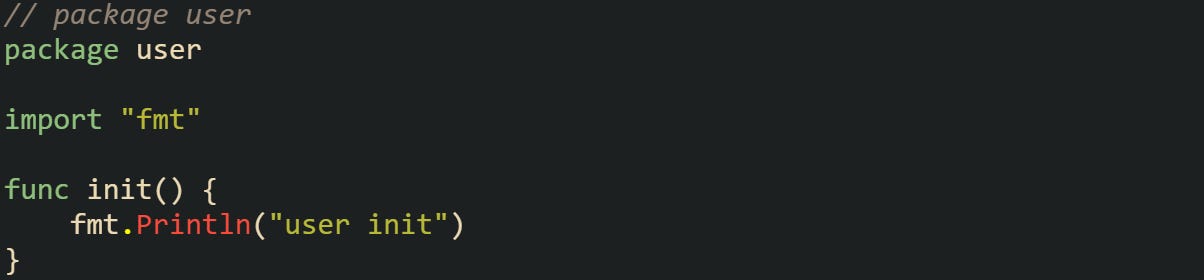

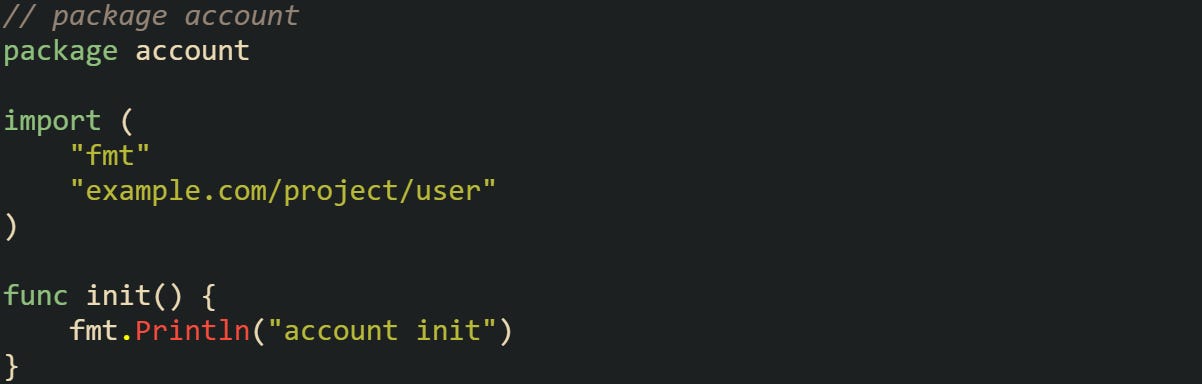

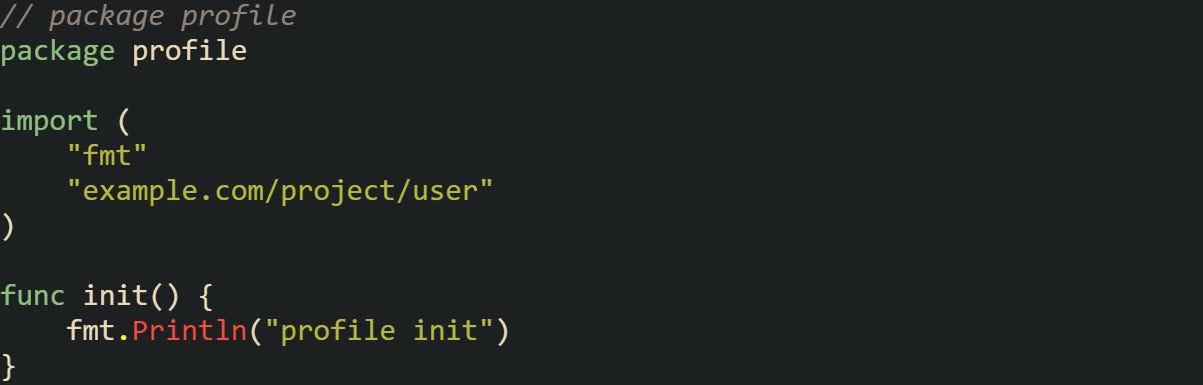

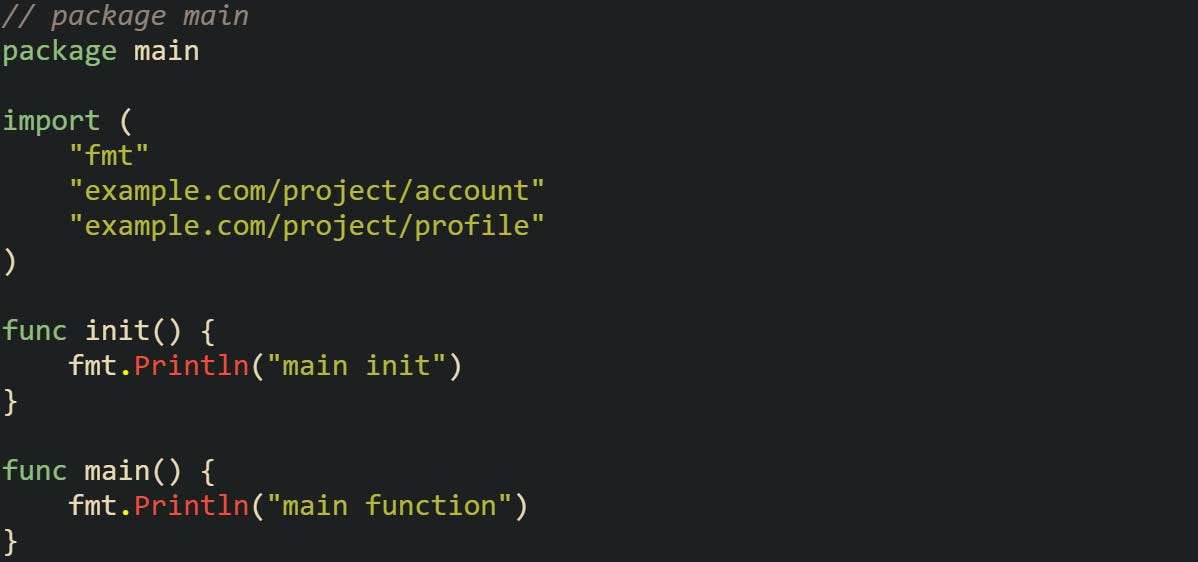

The effect of all these rules is easier to see with a complete example that spans multiple packages.

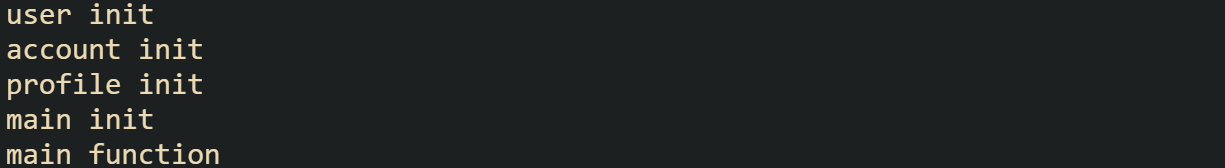

Running this prints:

user runs first because both account and profile depend on it. Each of those then runs in turn, and only after they’re both finished does the main package start. This small chain shows how Go’s import order produces a stable sequence no matter how many packages are involved.

Conclusion

Go follows a predictable path when it comes to preparing packages. Variables are assigned first, init functions run afterward, and dependencies always finish before the packages that rely on them. Import order drives the sequence, and every package is initialized only once, even if pulled in from multiple places. With these rules in place, the runtime delivers a consistent starting point so that by the time main runs, every package in the chain is fully prepared.