Text search in relational databases usually starts from a basic need to filter rows by a name, title, or description when a user types only part of a word or phrase. At a small scale, a filter with the LIKE operator can feel fast enough as queries read only a modest number of rows. As tables grow to millions of records, the same filter can force long scans across indexes or even the whole table if the search expression does not line up with how data is stored. Partial matches stay fast when the database pairs the right search operators, such as LIKE, full text search features, and trigram based extensions, with index structures that match the way text values are accessed.

How Partial Text Search Works With Indexes

Partial text search sits where human friendly filters meet storage rules inside a database engine. Users sometimes type part of a product name, a piece of an email address, or a single word from a long description, and expect the application to bring back the right rows with only that fragment to work with.

Index structures decide how much data the engine has to read to answer that request. B tree indexes on text columns hold values in sorted order and let the engine jump to a position that matches a given value or a range of values. When conditions with LIKE match the way values are laid out in that index, searches stay close to index range scans. When a condition hides the prefix or wraps the column in a function, the planner loses that benefit and drifts toward scans that touch a large part of the table.

Basic Pattern Matching With LIKE

Many SQL queries that search text start off with the LIKE operator. This operator treats text as a sequence of characters and compares it to a template that can include wildcard symbols along with normal letters or digits. LIKE understands two wildcard characters. The percent sign % stands for any sequence of characters, including an empty string. The underscore _ stands for a single character. All other characters in the match string have to line up exactly, subject to collation and case sensitivity rules in the database.

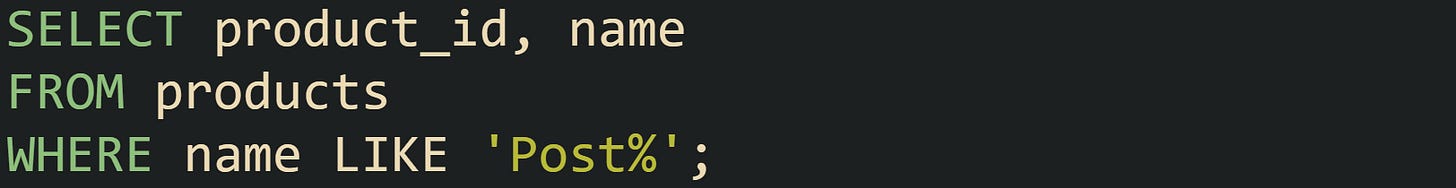

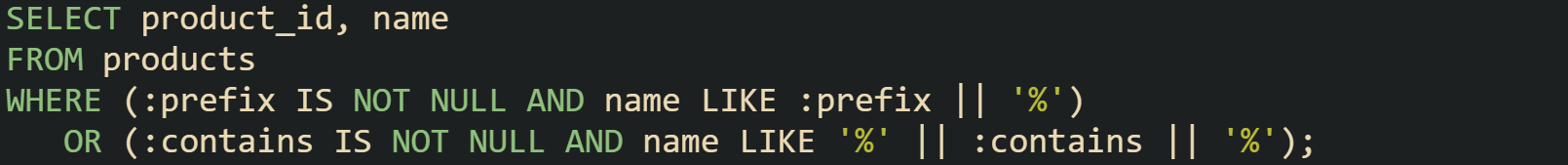

Let’s look at a filter that looks up products by prefix and fits this model:

This condition has a constant prefix Post followed by a wildcard. On a B tree index built on products(name), many engines can treat this as a range that starts at Post and ends just before the next possible string after that prefix. That lets the engine scan only a slice of the index, not the entire table.

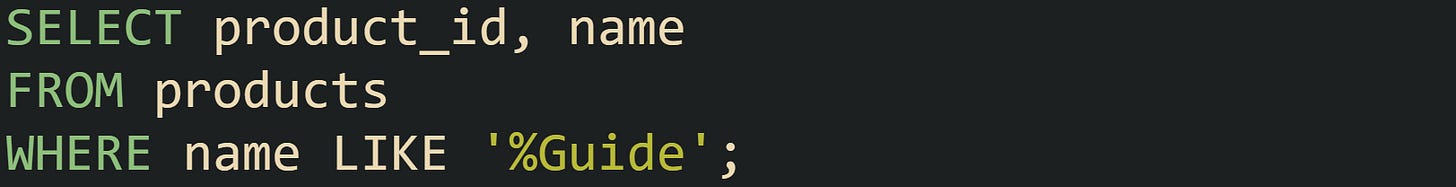

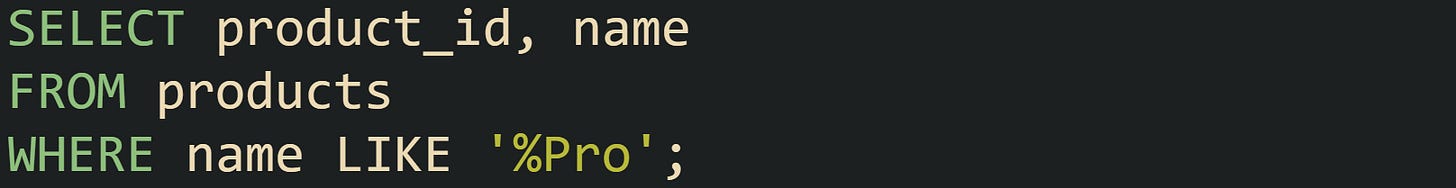

Suffix matches keep the wildcard at the front and fix the tail of the string instead:

This kind of match has no fixed beginning, so the engine cannot map it to a contiguous range in a B tree index on name. A common plan in that case is a full scan of the table or a scan of every entry in the index, with the LIKE comparison applied row by row.

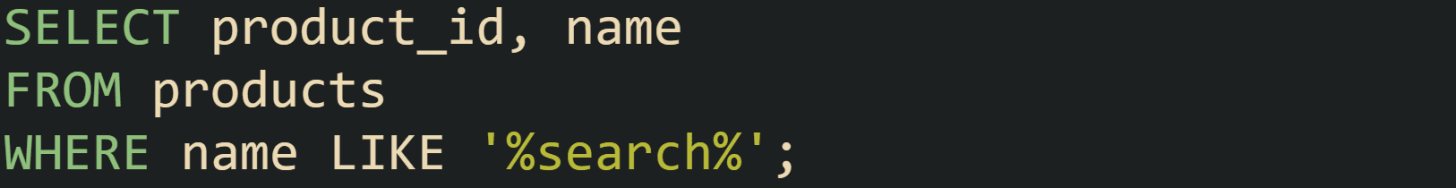

Substring matches fall into the same category:

With wildcards on both sides, the database must examine many values to see which ones contain that middle fragment. A normal B tree index on name does not help much with that predicate.

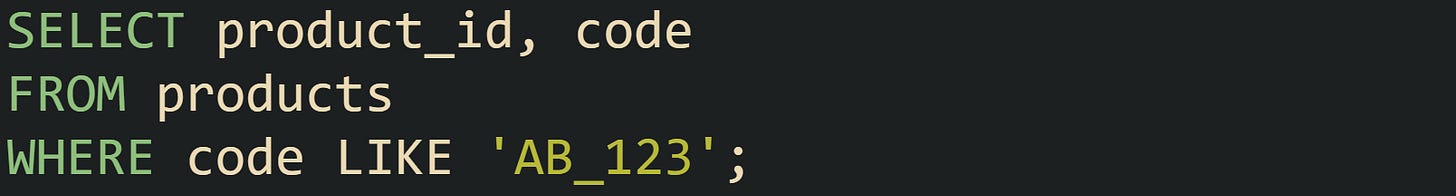

The underscore wildcard matches a single character position and keeps the rest fixed:

This condition says that the first two characters must be A and B, the fourth through sixth characters must be 1, 2, and 3, and the third character can be anything. Index support here depends on the database engine and collation rules. Some engines can still use the fixed prefix AB to find a starting point in the index and then apply the full match expression as a filter on rows that share that prefix.

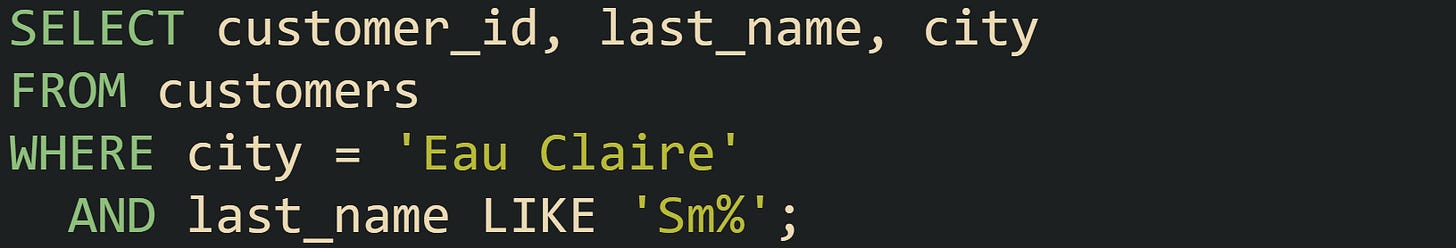

Real applications frequently combine LIKE with other predicates. Many customer search pages only allow queries inside one city or one status flag:

The equality on city narrows the set of rows that need to be checked, and the prefix Sm% can align with an index on (city, last_name) in that order. Index choices on multiple columns become important in those cases, because the leftmost column or columns in the index define how the B tree is laid out and what range of LIKE prefixes keep the scan narrow.

Limits Of Plain LIKE On Large Tables

Large tables change how LIKE behaves in practice. Filters that feel acceptable on a few thousand rows can turn into heavy operations on tens of millions of rows when the index cannot help.

Search strings that begin with % cause trouble first. Take this for an example:

Here, the code runs against a large catalog, the engine has no way to guess where names that end in Pro sit inside a sorted index. That usually leads to a plan that touches the full table or the full index and applies the LIKE check to every candidate value. With enough rows, that plan pushes latency up and increases load on the storage layer.

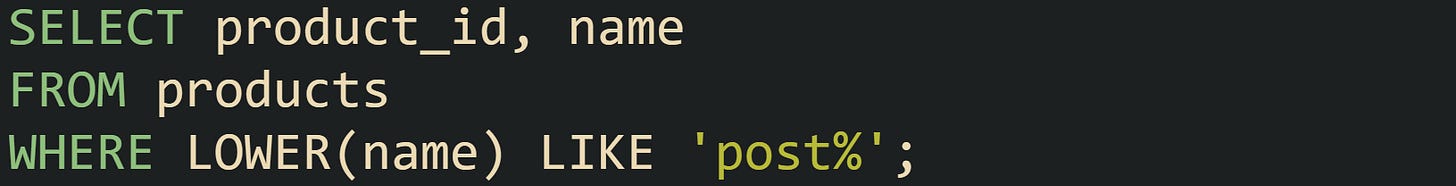

Computed expressions inside the predicate cause similar trouble. Many codebases want case insensitive search and reach for LOWER or UPPER calls:

Plain indexes on name no longer match that condition, because the stored index entries hold the original text while the predicate runs against lowercased text. Several engines, including PostgreSQL and Oracle, support indexes built on expressions such as LOWER(name) so that queries can use the transformed text directly in the index. When that index is not present, the engine falls back to a scan.

Function calls that trim whitespace or remove accents have the same effect. Any expression that changes the value the index sees makes a normal index on the base column less helpful unless a matching index on the expression exists.

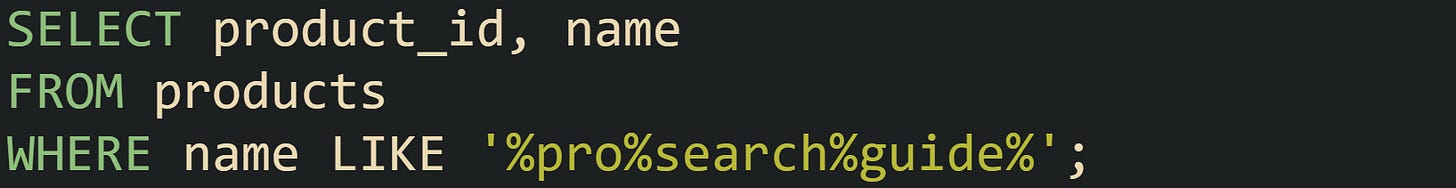

Multiple wildcards in the middle of a search string increase the cost as well.

This asks the engine to find rows containing pro, then later search, then later guide, all in that order, without any help from an index on the original column. For long strings and large tables, that type of search scans many bytes per row.

Parameter driven search interfaces bring an extra challenge. One field can accept a prefix search, while another allows a contains search, depending on user input:

Query forms like this lead to different access patterns at runtime. Prefix search can work with an index, while contains search does not. Query planners inspect the constants or bound parameters at execution time and decide how much of the index can help, but parts of the filter that begin with a wildcard tend to fall back to scanning.

These limits pushed database vendors to add features geared toward indexed text search such as full text search and trigram style matching. Those features build on different index structures and search strategies and address cases where LIKE alone cannot keep partial text search fast on very large data sets.

Indexing Strategies For Partial Matches

When the index structure lines up with how the query engine reads text, partial text search becomes much more practical. Queries that only need prefixes can lean on ordinary B tree indexes, while word based search benefits from inverted indexes that map terms to rows. Substring search and fuzzy matches depend on structures that store short character fragments such as trigrams. All of these live side by side and address different types of text filters that appear in real applications.

Databases bring these strategies to life through specific index types and operators. B tree indexes back up LIKE 'prefix%' filters. Full text indexes support boolean and ranked search against large bodies of text. Trigram indexes and related features in extensions push partial and typo tolerant search toward index backed plans instead of table wide scans. Getting comfortable with how each one works makes it easier to pick the right option for a given search screen or API endpoint.

Prefix Search With B Tree Indexes

Many user interfaces ask for the beginning of a value rather than the full string. Autocomplete on customer last names, suggestions for city names, or product codes typed into a search box all fit this kind of prefix search. B tree indexes handle these cases well when queries keep the leading characters fixed and place wildcard symbols only at the end.

B trees store values in sorted order and arrange index entries in pages that connect through a tree of pointers. When a query looks for a range of values, the engine can follow the tree down to the first matching value and walk through pages in order until the range ends. Prefix searches match that behavior closely, because strings that share a prefix sit next to one another in the index.

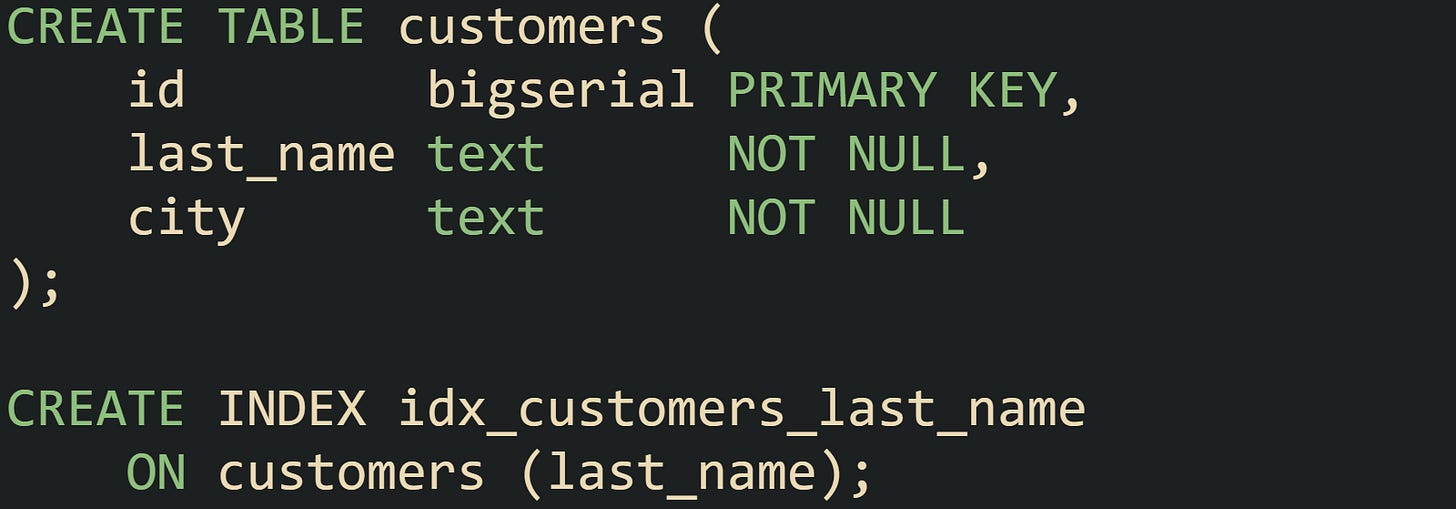

This PostgreSQL example makes this a bit easier to see:

With that index in place, a query that matches a prefix has a good chance of using it:

The planner can translate LIKE 'Sm%' into a range that starts just before Sm and ends just before the next possible prefix after Sm. That plan scans only the range of index entries whose last_name values begin with Sm and then retrieves the matching rows from the table.

MySQL and SQL Server apply the same basic idea to LIKE 'prefix%' on indexed CHAR or VARCHAR columns with compatible collations. A WHERE last_name LIKE 'Sm%' condition on a plain index INDEX(last_name) typically turns into an index range scan rather than a full read of the table. Case sensitivity plays a part here. Columns stored with case insensitive collations can match Sm% for both Smith and smith, while case sensitive collations treat those as separate values.

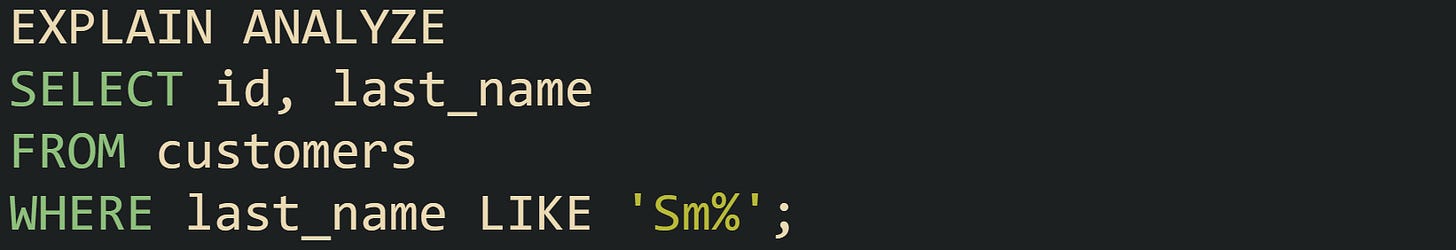

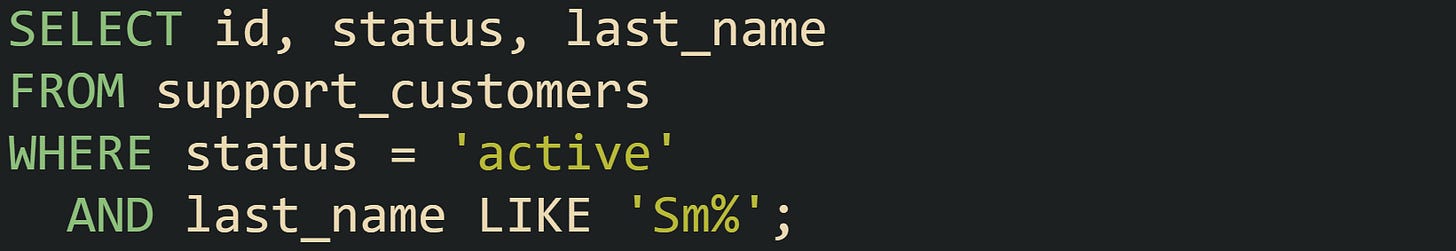

Queries that blend equality and prefix search across multiple columns can still benefit from B tree indexes when the index column order aligns with the filter. Let’s say we are working with a support tool that keeps customer records with status flags and names:

Searches against active customers whose last names start with Sm fit this index:

The index is sorted first by status, then by last_name. With status = 'active' fixed and last_name LIKE 'Sm%' expressing a prefix, the engine can walk a compact section of the index that covers exactly those rows instead of scanning inactive records.

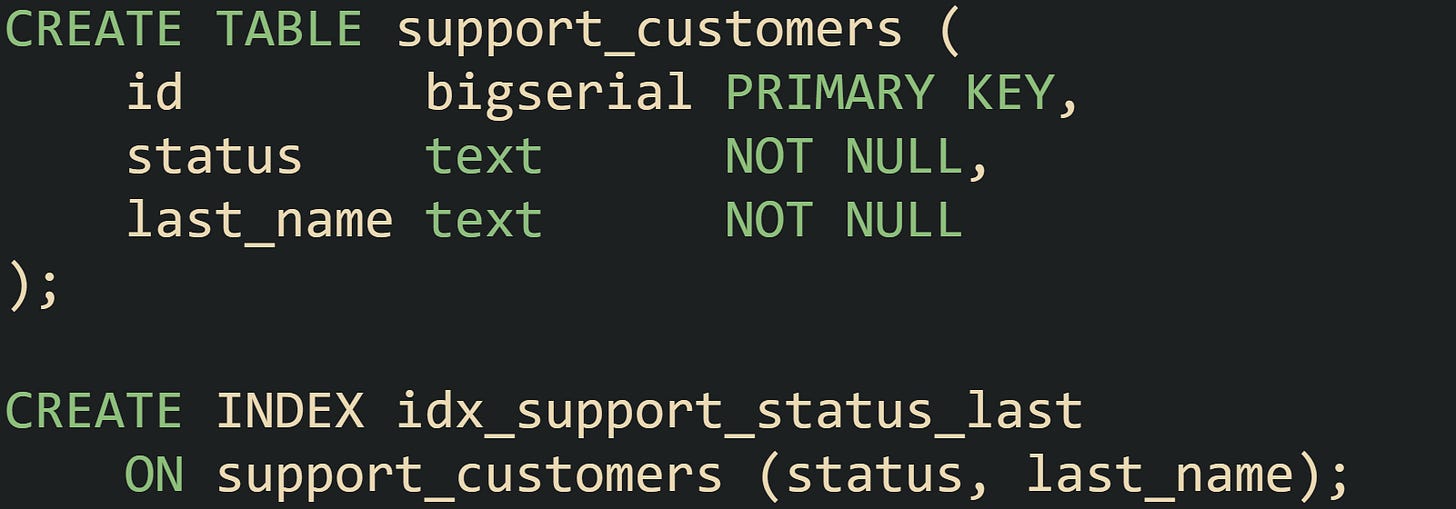

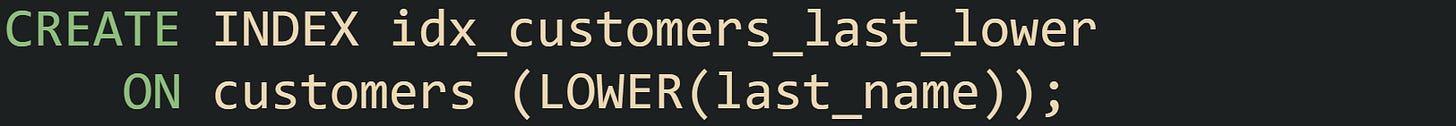

Case insensitive prefix search benefits from functional indexes in engines that support them. PostgreSQL, for example, can store lowercased names directly in the index:

Queries then match against the transformed value:

This query form avoids lowercasing every row during the scan and lets the engine use the index entries that already hold LOWER(last_name) values. Similar ideas appear in Oracle and in other systems that support indexes on expressions, with syntax differences but the same basic goal of lining up the index with the expression in the filter.

Prefix search with B trees works best when queries avoid wildcards at the front of the string and limit function calls on the indexed column. As long as filters keep that prefix intact and match the expression stored in the index, the engine has a good chance of treating the request as a range scan instead of a full scan.

Full Text Search For Word Based Matching

Applications that deal with article bodies, support tickets, product descriptions, or chat transcripts need more than prefixes. Users expect to type a few words and see matching content with some ranking applied. B tree indexes on plain text columns do not have enough structure for that style of search, so engines rely on full text indexes that act more like term dictionaries. Full text indexes usually work by breaking text into tokens and building an inverted index. Instead of mapping each row to its values, the system maps each term to the list of rows that contain it, sometimes with extra details such as term frequency or positions. This layout mirrors what search engines use and makes it possible to fetch candidate rows quickly for a given set of terms.

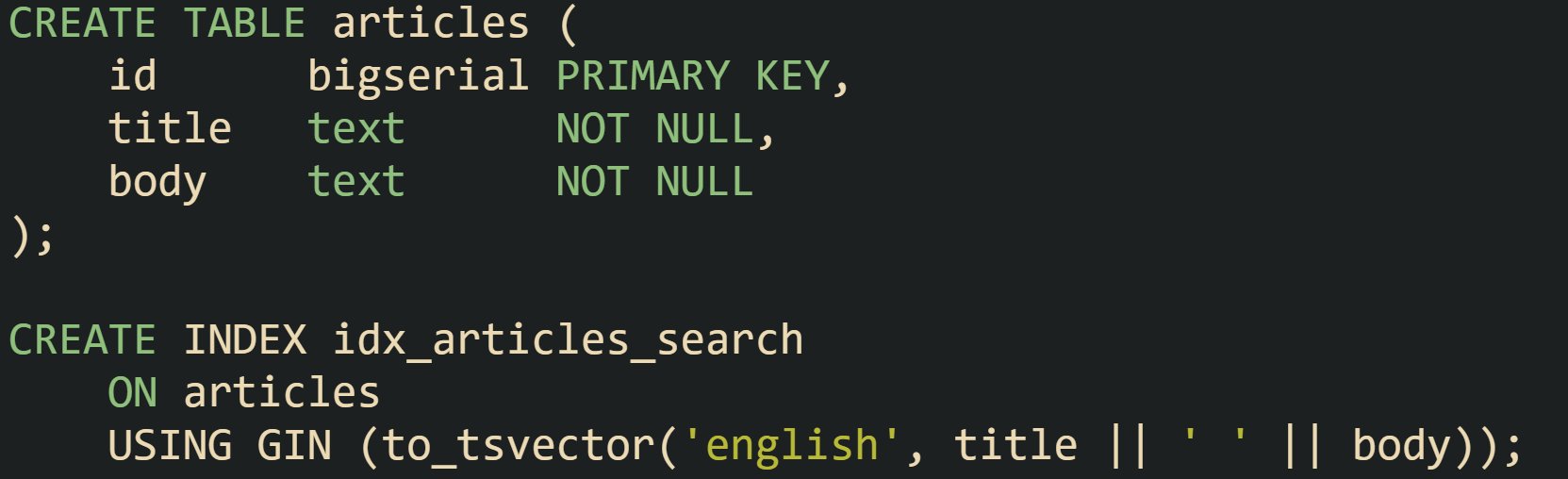

PostgreSQL supports full text search through tsvector and tsquery types combined with GIN or GiST indexes. A typical table can look like this:

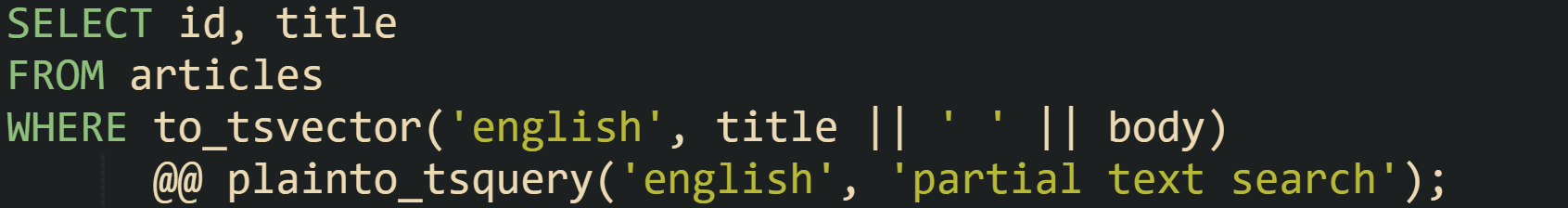

The index stores the tsvector representation of title || ' ' || body. That representation contains normalized tokens for words in the text, usually lowercased and stripped of suffixes according to the selected configuration such as english. Queries build a tsquery value and apply the @@ operator to match those tokens:

In this code, the planner uses the GIN index to find rows whose token sets satisfy the tsquery. Binary operators in the query string such as &, |, and ! express logical conditions between terms, and weights or ranking functions can adjust ordering in result sets.

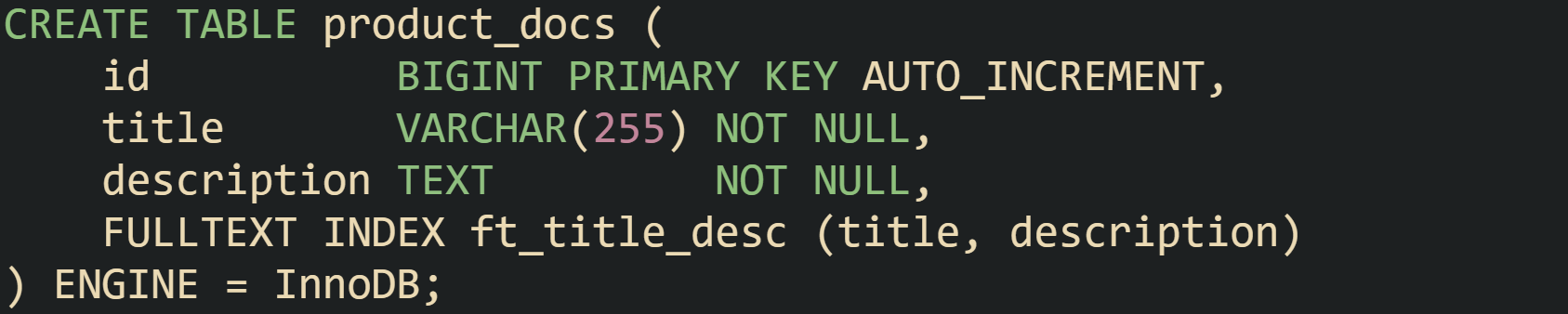

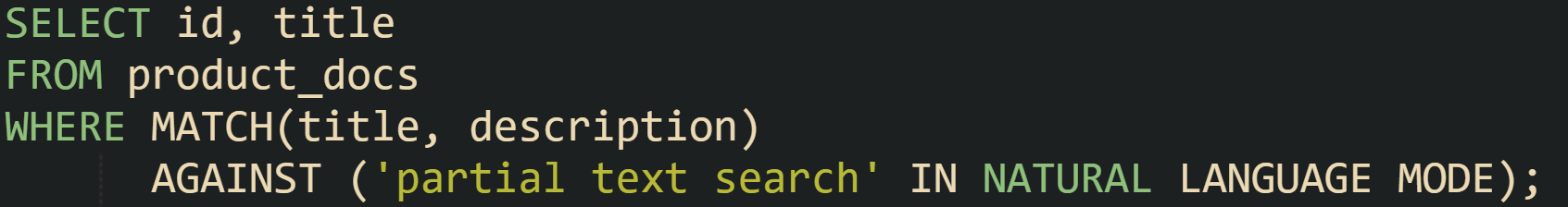

MySQL follows a similar concept with FULLTEXT indexes on CHAR, VARCHAR, and TEXT columns. Developers can declare an index like this on an InnoDB table:

Queries then use MATCH and AGAINST:

The FULLTEXT index organizes terms and document references so that searches over large text columns can avoid row by row scans. Boolean mode queries add operators such as + and - to require or exclude terms.

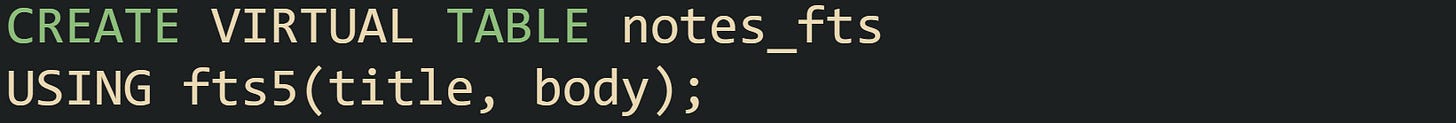

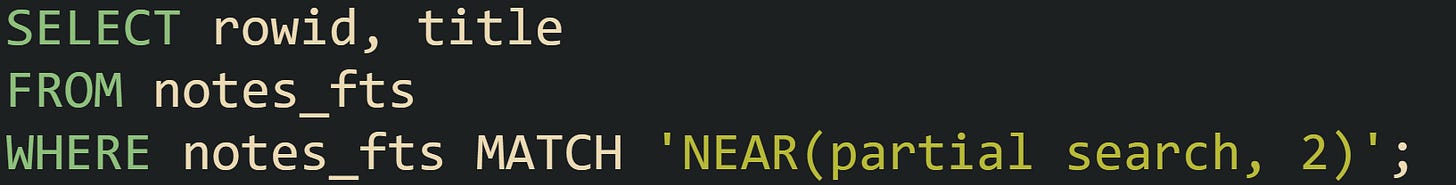

SQLite handles full text search through FTS virtual tables like FTS5. Rather than adding an index to an existing table, the database stores content inside a special table that maintains its own full text index:

Inserts and updates into notes_fts update the full text index automatically. Queries use a MATCH operator with a search string:

That search looks for rows where partial and search occur within two tokens of each other. Ranking functions such as bm25 can then order results by relevance.

All of these systems trade more complex index maintenance at write time for fast reads on multi word queries. Tokenization, stopword lists, stemming, and language configurations vary between engines, but the shared goal is to treat text as a bag of terms and store those terms in a structure that makes term based search fast.

Trigram Indexes For Fuzzy Partial Search

Substring search and typo tolerance call for a different strategy. Queries that look for fragments buried inside a word or short string, or that need some tolerance for misspellings, do not map neatly onto plain full text indexes. Many engines address that niche with trigram techniques and related extensions.

Trigram methods break strings into overlapping chunks of three characters. For the text search, one common set of trigrams would be sea, ear, arc, rch, sometimes with extra boundary markers added at the start and end. When an index stores these trigrams, the engine can compare trigram sets between the search term and stored values, then treat higher overlap as a sign of similarity or as a way to filter candidates for a substring match.

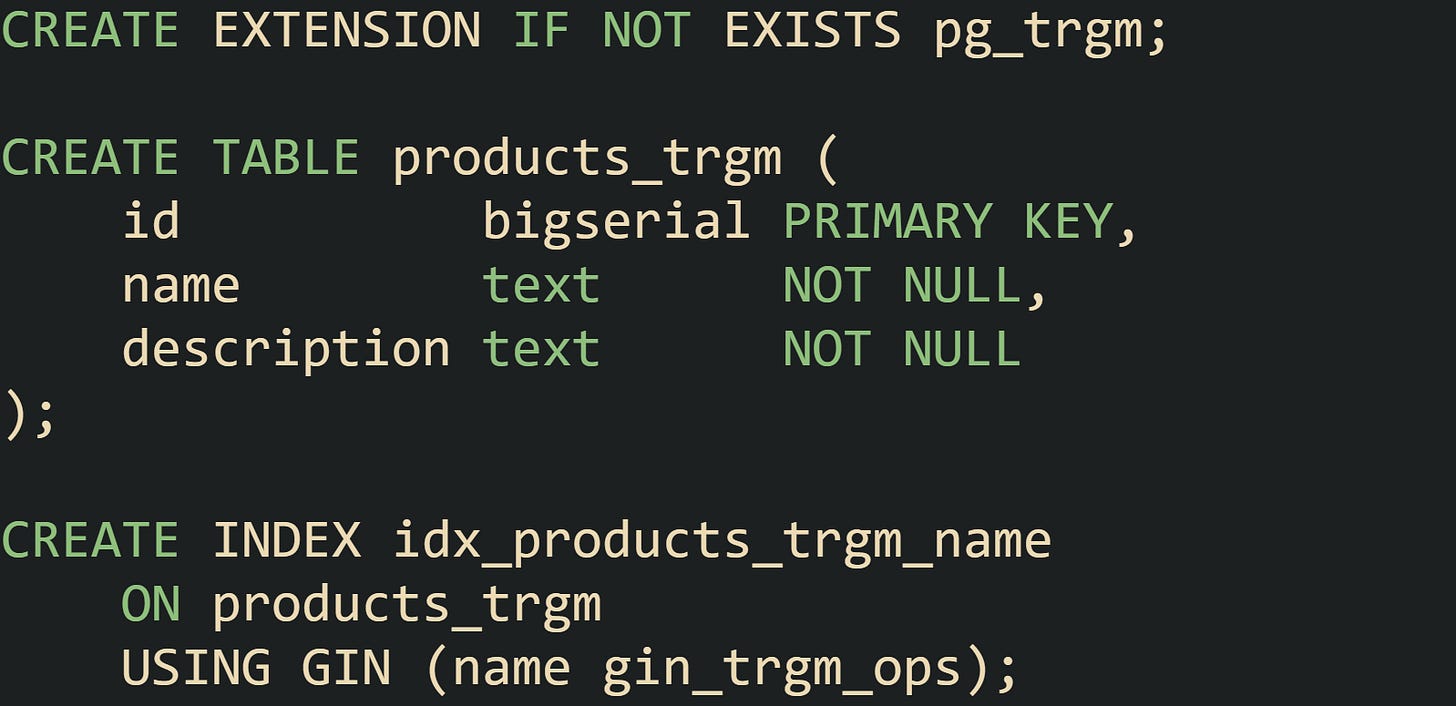

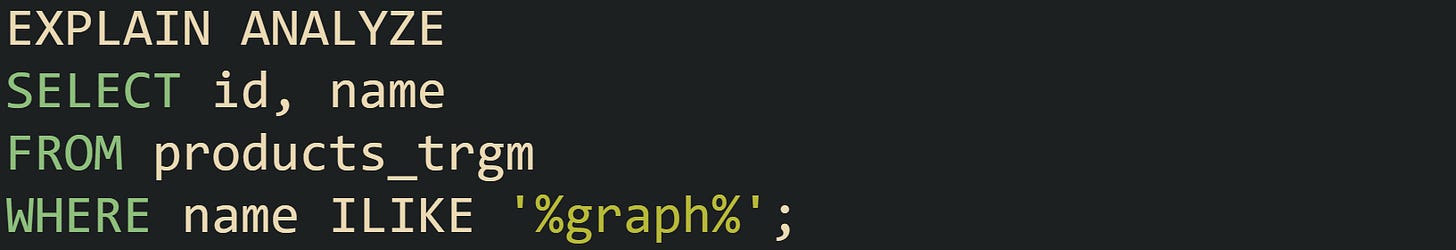

PostgreSQL brings trigram support through the pg_trgm extension. After enabling the extension, indexes can store trigram data and speed up LIKE, ILIKE, regular expression matches, and similarity operations.

With that GIN index on name, substring search across a large product catalog becomes more practical:

The planner can rely on trigram overlap between graph and stored names to pick a reduced set of candidates. Only those rows whose trigram sets share enough three character chunks with graph need to pass through the full ILIKE comparison. This narrows the search space even though the wildcard sits at the beginning of the LIKE pattern.

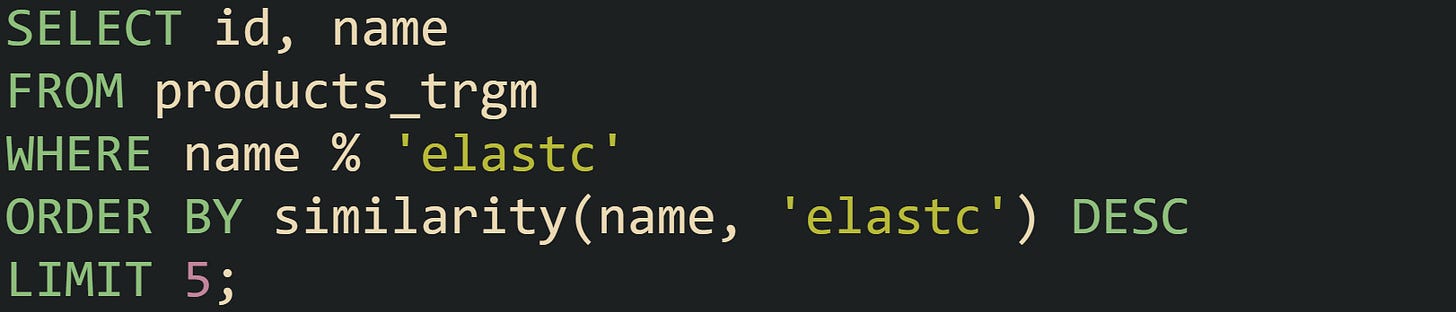

The pg_trgm extension also supplies similarity operators and functions, which support nearest neighbor style queries. One search for names close to a user supplied term uses one of these operators:

Typos such as elastc instead of elastic still return reasonable matches, ordered by their trigram similarity scores. A GIN or GiST index on the trigram representation keeps such searches responsive on large tables.

Other ecosystems adopt related ideas. MySQL offers an ngram full text parser that splits text into fixed length fragments and feeds them into a full text index, which works well for languages without clear word boundaries and also helps with substring matches in some workloads. Third party extensions and libraries for SQLite and other databases implement trigram or ngram search in various ways, always with the same basic goal of storing short character fragments in a way that supports partial and fuzzy matching on large data sets.

Conclusion

In practice, partial text search performance comes down to how string operators interact with index structures. LIKE with anchored prefixes rides on B tree ranges, full text indexes route word based queries through token lists, and trigram indexes narrow substring and fuzzy matches by comparing short character sequences. Matched mechanics let databases scan far less data, keep latency low, and still support flexible search behavior as tables grow.