Database queries depend on matching text in names, emails, or search terms while ignoring letter case. Matching ALEX should find alex or Alex and behave the same across MySQL, PostgreSQL, and SQL Server. Each engine handles text comparison rules through collations, built in operators, and functions that decide how characters compare during equality checks or wildcard searches.

Case Handling Rules in Modern Engines

Simply put, case handling in relational databases comes down to a mix of collation rules, function calls on text, and how match expressions behave in different operators. Engines do not look at characters in isolation, they compare them through rules that say whether A equals a, how accents line up, and how text from different languages should sort. Queries that feel similar at the SQL level can act very differently once collations and functions interact, so it helps to know where case sensitivity is controlled in MySQL, PostgreSQL, and SQL Server before writing filters for names, emails, or search terms.

Collation Behavior

Collation defines how characters compare and sort inside a database. Many collation names pack several ideas into one label, such as the character set, language, case sensitivity, and accent sensitivity. MySQL 8 usually pairs new utf8mb4 databases with utf8mb4_0900_ai_ci, where ai signals accent insensitivity and ci signals case insensitivity. Queries on that collation read Alex, ALEX, and alex as equal for equality checks and sort order.

Take this MySQL example to inspect default collation:

This query helps confirm which collation drives comparisons at the server and database level before any column level overrides.

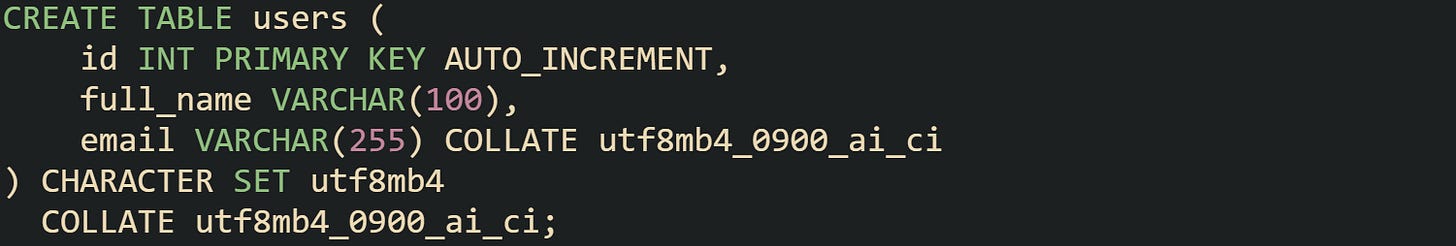

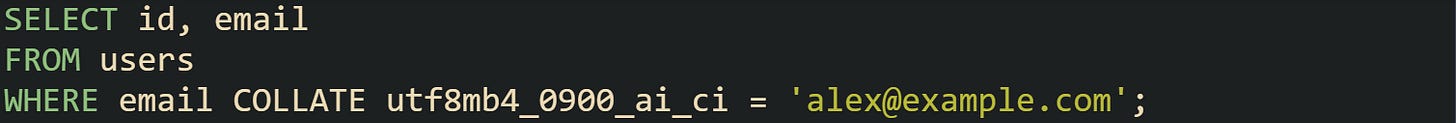

For MySQL, here is a example with an explicit case insensitive collation on a table:

Columns on this table treat alex@example.com and ALEX@example.com as equal for basic comparisons, and indexes on email follow that rule as well.

PostgreSQL handles collations through the operating system or ICU, with settings at the database and column level. A typical cluster leaves the default collation tied to the system locale, and columns inherit that unless an explicit choice appears in the definition.

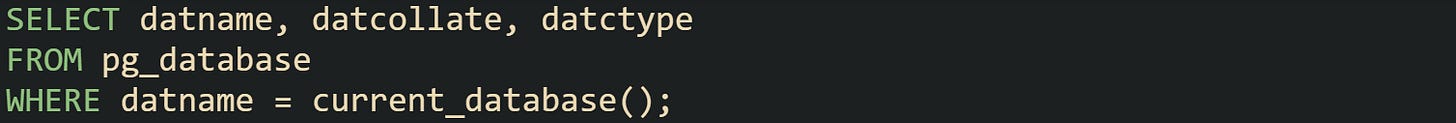

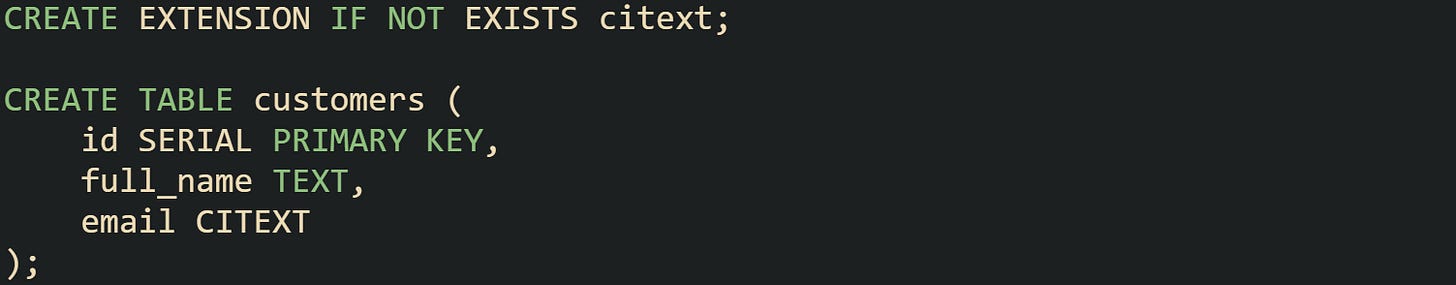

Let’s look at PostgreSQL example to see collation on the current database:

And for explicit collation on a column in PostgreSQL:

Columns declared with a collation control how text sorts and how operators such as LIKE behave, but a common en_US.utf8 style collation does not make = comparisons case insensitive. For case insensitive equality in PostgreSQL, use the citext type, or normalize with LOWER() and support that with an expression index.

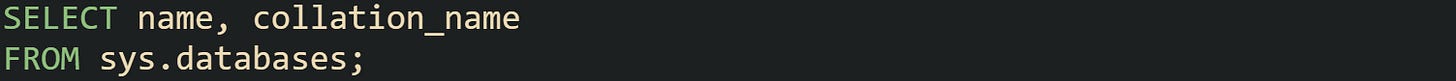

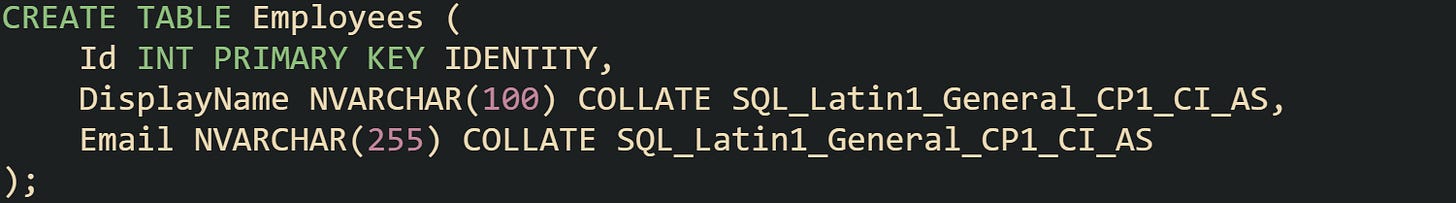

SQL Server builds collation rules right into database and column metadata. Names such as SQL_Latin1_General_CP1_CI_AS encode language, code page, case sensitivity, and accent sensitivity. Suffix CI marks case insensitive comparison, and CS marks case sensitive comparison.

Take this SQL Server code to inspect database collations:

For SQL Server with an explicit collation on a column:

Columns on this table treat Alex and alex as equal when queries rely on the default comparison rules. Indexes on DisplayName or Email keep those same case rules for search and sort.

Function Based Comparison

Function calls on text give another layer of control over case handling. LOWER and UPPER appear in all three engines and convert a string to one case before comparison. This gives reliable matching even when columns sit on collations that treat case differently, or when expressions combine text from several sources with mixed rules.

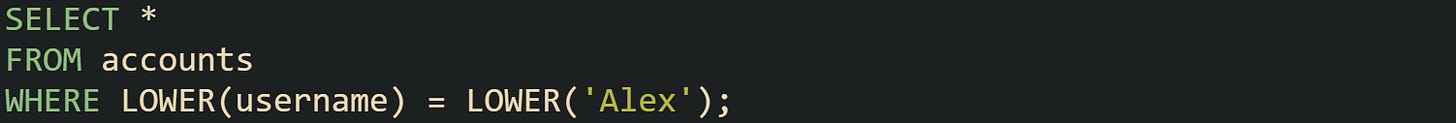

Let’s look at a example with MySQL filtering usernames through LOWER:

This query matches Alex, alex, or ALEX in the username column even if that column sits on a case sensitive collation. Both sides of the comparison move to lower case, so the result does not depend on how values were typed or stored.

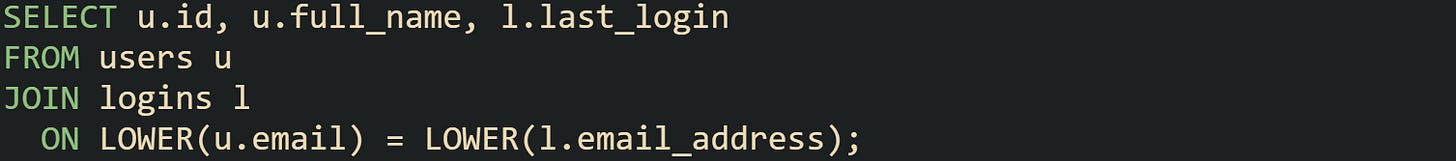

PostgreSQL query that joins two tables with different collations:

Email values from users and logins end up in the same case before the join condition runs, so mismatched casing between systems does not block the join.

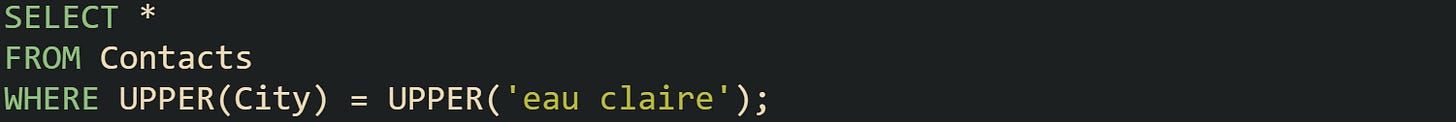

This SQL Server query searches contacts by city with UPPER:

Queries like this help align user supplied text with stored data, even when users type city values in different ways. Function based comparison also appears in computed columns and expression indexes, which lets a database keep an indexed version of LOWER(column_name) for common search paths.

Practical Query Methods for Case Insensitive Matches

Case insensitive text in real databases usually depends on a combination of collation choices, function calls, and operators that line up with how data was created. Case behavior can change based on column definitions, database defaults, and how user input is transformed before comparison. Names, emails, and search boxes benefit from stable habits in queries, where similar filters always apply the same rules for case and keep search results predictable across MySQL, PostgreSQL, and SQL Server.

Collation Set Queries

Collation changes at query time help when data lives in a database that leans toward case sensitive defaults or when different teams have created tables with mixed rules. A collation tag attached directly to an expression tells the engine to treat that part of the filter as case insensitive without rewriting the table definition. That kind of change works well during gradual migrations, because columns remain in place while queries adapt.

This is how MySQL adjusts collation inside a filter:

User input such as ALEX@example.com or Alex@example.com still matches, because the comparison for email runs under utf8mb4_0900_ai_ci rules. An index on email that uses the same collation can still support this predicate, so searches do not fall back to table scans purely because of case handling.

Different columns in one schema can carry different collation choices on purpose. Teams sometimes want case sensitive usernames and case insensitive emails, or they may inherit tables from different applications. Expression level collations smooth out filters for columns that did not get a case insensitive collation at creation time. SQL Server queries can tag expressions in a similar way.

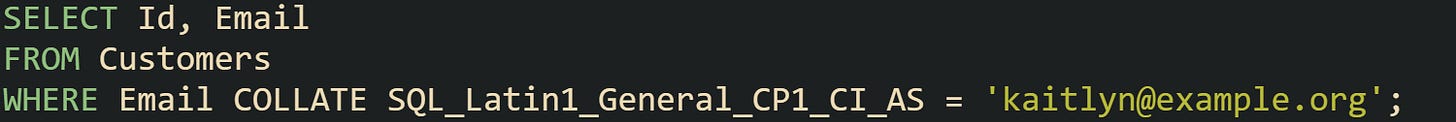

This filter in SQL Server forces case insensitive comparison for a single predicate:

That COLLATE clause overrides any case sensitive database default, so Email values with different letter casing still line up for equality checks. Indexes on Email created with the same CI collation remain useful, because stored values and query comparison rules still agree.

PostgreSQL relies more on column level collations or ICU based definitions set at table creation time, and on functional strategies described later. Expression collations exist but tend to play a smaller part in day to day case insensitive search compared with MySQL and SQL Server.

Function Based Queries

Function calls on text give queries a way to normalize user input and stored values without touching table structure. Calls to LOWER or UPPER bring both sides of a comparison into the same case, which removes letter casing as a variable even when columns live on a case sensitive collation. This helps with data from older systems, imported feeds, or shared databases where different applications use different casing habits.

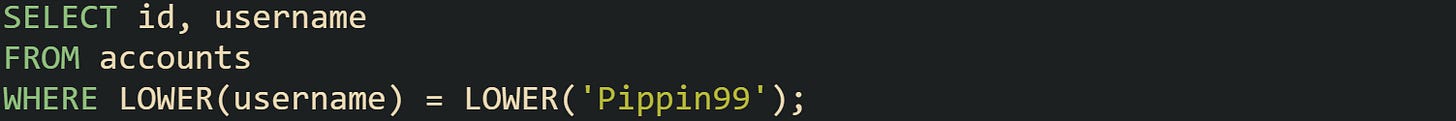

MySQL filters on usernames often use this style when collation rules are uncertain:

Usernames such as pippin99, PIPPIN99, or PipPin99 all match, because both the column value and the literal pass through LOWER before comparison. A functional index on LOWER(username) in MySQL 8 ties directly into this predicate and keeps response times stable as the accounts table grows.

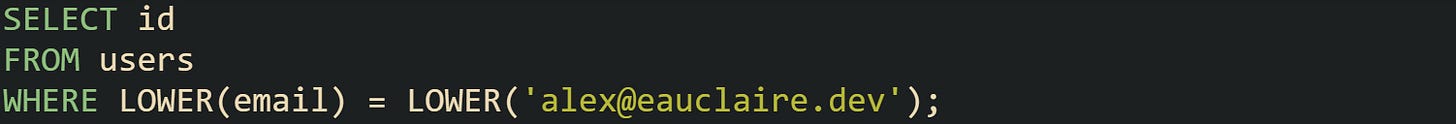

PostgreSQL relies heavily on function based comparison when integrating data from multiple sources. Email addresses stored by one system might use uppercase domains, while another system stores lower case values. A login query that normalizes both sides avoids surprises.

PostgreSQL login check driven through LOWER can look like this:

Supporting expression index anchors that filter to an index.

PostgreSQL index definition for lower cased email values:

After that index exists, filters that repeat LOWER(email) in the predicate can use an index scan rather than reading every row. That pairing of query expression and index expression keeps both speed and behavior aligned.

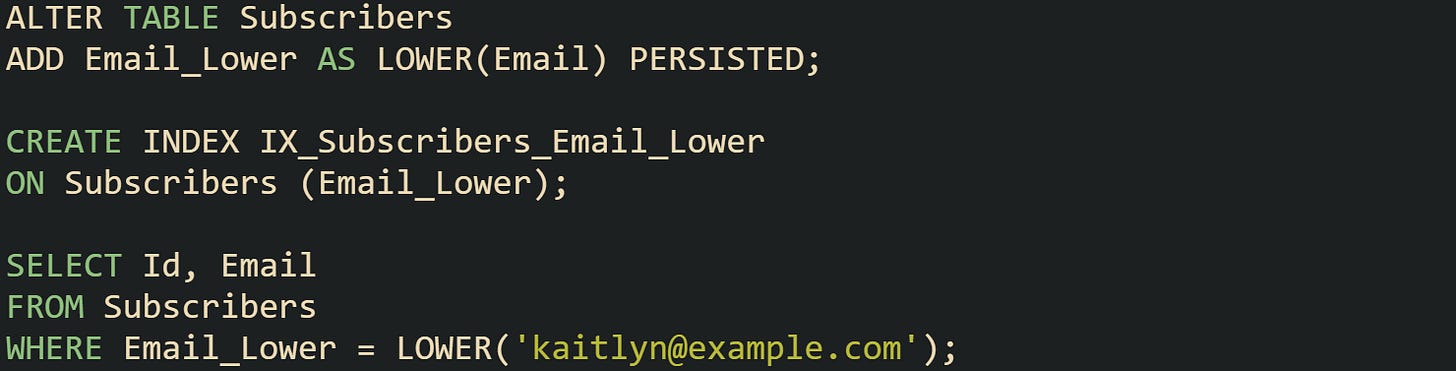

SQL Server leans on computed columns when the same function based comparison appears across many queries. A persisted computed column based on LOWER or UPPER lets the engine store the normalized value on disk and index it like any regular column.

This is a common SQL Server pattern for lower cased emails:

Normalization moves into the computed column, and filters reference Email_Lower directly. That structure keeps email display values unchanged in the base column while giving a consistent entry point for case insensitive search.

Pattern Match Queries

Search features that use wildcards raise extra questions about case behavior. Filters on names, city fields, product titles, and message subjects very frequently rely on partial matches, where user input might match the start, middle, or end of stored text. Operators such as LIKE and ILIKE interpret % as a multi character wildcard and _ as a single character wildcard, and collation rules dictate how letter case affects those matches. MySQL evaluates LIKE in line with the collation for the column. Case insensitive collation on a column keeps comparisons case insensitive even when wildcards are present.

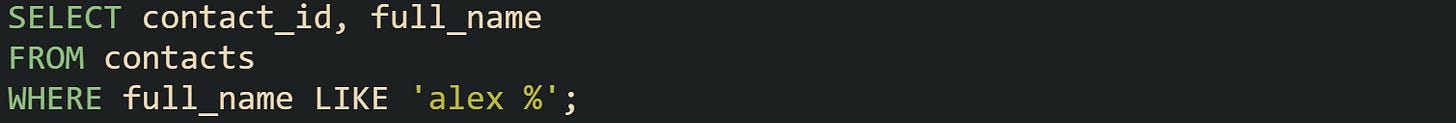

This MySQL query searches contact names with a trailing wildcard:

Rows such as Alex Martin, alex Johnson, and ALEX KING all satisfy the filter when full_name uses a case insensitive collation. The comparison logic folds letters into the same character class before testing the prefix alex segment against stored values.

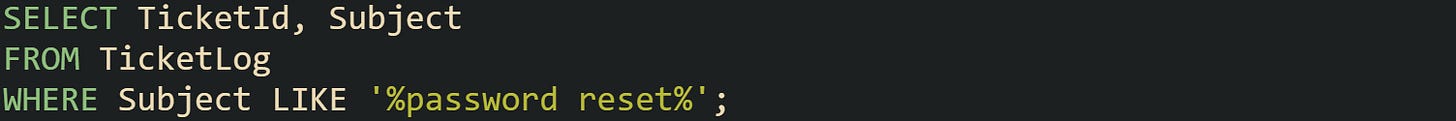

SQL Server handles LIKE in a similar fashion for columns that use a CI collation. Case differences do not affect match results, though index behavior still depends on where the wildcard appears.

This SQL Server search scans ticket subjects for a phrase:

Subjects including Password Reset, PASSWORD RESET, or password reset all match as long as the Subject column carries a case insensitive collation. Leading % reduces the chance of an index seek and usually leads to a scan, while predicates like Subject LIKE ‘Reset%’ can take advantage of ordered index structures on that column.

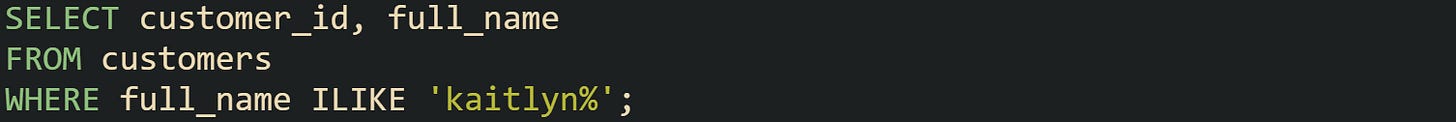

PostgreSQL separates case sensitive and case insensitive wildcard behavior through two operators. LIKE respects case in many collation setups, so LIKE ‘alex%’ only matches entries beginning with alex in that exact casing. ILIKE applies case folding inside the operator so that Alex, ALEX, and alex match the same search prefix.

A PostgreSQL query for a case insensitive name prefix with ILIKE can look like this:

Full names such as Kaitlyn Reed and kaitlyn ross both meet that condition, because ILIKE removes letter casing as a factor. For domain searches or substring searches, expressions like email ILIKE ‘%@example.org’ follow the same principle. Workloads with frequent wildcard searches sometimes pair ILIKE with trigram indexes or full text extensions so that match operations scale well on large tables.

Index Friendly Queries

Case insensitive queries benefit from index layouts that match their comparison rules. Filters that rely only on expressions such as LOWER(column) without supporting indexes usually drift toward full scans as data volume grows, even if correctness remains intact. Aligning collations, function usage, and index definitions keeps both accuracy and performance on track.

MySQL tables that use utf8mb4_0900_ai_ci for user facing text gain case insensitive equality and prefix search behavior naturally through standard B tree indexes. Queries such as WHERE email = ‘alex@example.com’ or WHERE email LIKE ‘alex%’ on columns with that collation can use regular indexes without extra expressions. Functions on the column side of the predicate such as LOWER(email) remove that advantage unless paired with an expression index.

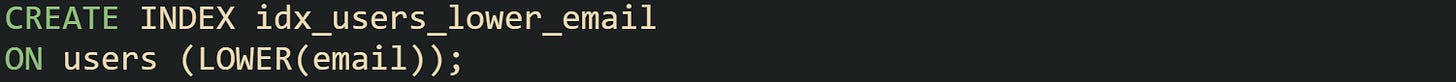

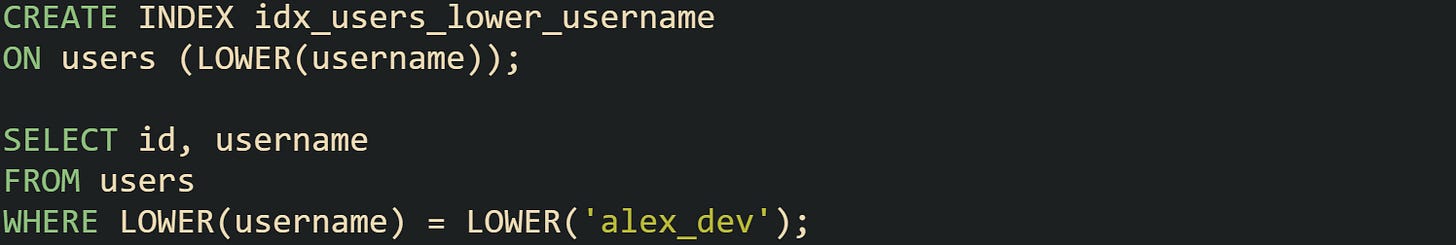

PostgreSQL takes a more explicit route with expression indexes. When a search strategy commits to LOWER(username) or LOWER(email) in predicates, an index on that expression turns the filter into an index friendly operation.

Take this PostgreSQL code tying an expression index to a username search:

Query text and index expression now match, so PostgreSQL can plan an index scan on idx_users_lower_username rather than visiting every row. This structure works well for login names, email addresses, and similar identifiers that appear frequently in filters.

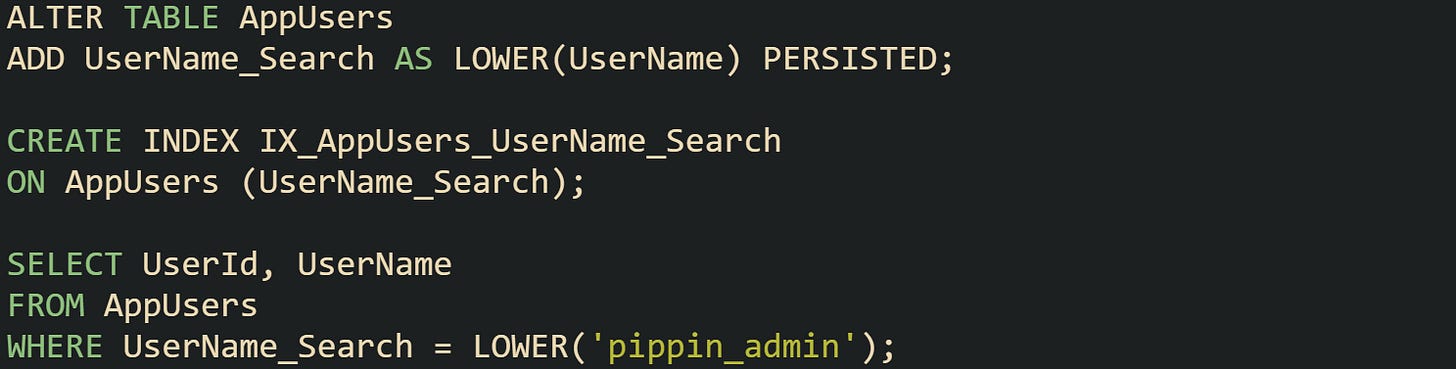

SQL Server tends to rely on persisted computed columns for this category of case insensitive queries. A computed column that stores lower cased or upper cased values forms a stable base for indexes and statistics, and queries either reference that column directly or let the optimizer map compatible expressions to it.

One common SQL Server layout uses a persisted search column for usernames:

Case insensitive search now centers on UserName_Search, while UserName retains the original casing for display or audit needs. Query predicates and index definitions line up, which keeps both function based normalization and index access working in a consistent way.

Conclusion

Case insensitive text matching across MySQL, PostgreSQL, and SQL Server rests on collation rules, function calls, and index layouts that share the same comparison logic. Collations decide how characters line up, functions such as LOWER and UPPER normalize values at comparison time, and indexes carry those rules into query plans so searches stay predictable as tables grow. Queries for names, emails, and search fields behave well when collation choices, function based expressions, and indexed structures match, giving consistent results regardless of how users type their input.

Solid breakdown on the collation vs function trade-off. The computed column approach in SQL Server is kinda underrated since most devs just slap LOWER() everywhere and wonder why scans keep happening. I hit this in a legacy system migrating from MySQL to Postgres where assumimg citext would fix everything missed the indexing layer completely. The ILIKE vs LIKE split in Postgres catches alot of people who think one collation ruleset applies universally across operators.