Programming languages keep moving forward to help developers write code that’s safer and easier to work with. Dart 3 brought two features into the language that push this effort further, records and pattern matching. Records give a lightweight way to group multiple values without the overhead of creating a class, while pattern matching provides a structured way to break values apart and act on them. Both features are deeply tied into the type system and compiler, so they operate as part of the language itself rather than just surface-level syntax.

Records in Dart 3

Records give Dart developers a way to group values together without having to create a class or rely on loosely typed structures like maps or lists. They’re part of the type system, so the compiler knows their layout and checks that values fit where they should. That makes them light to write but strong in terms of type safety. Because they’re fully recognized by the compiler and runtime, records feel like a natural extension of the language rather than a workaround.

What a Record Is

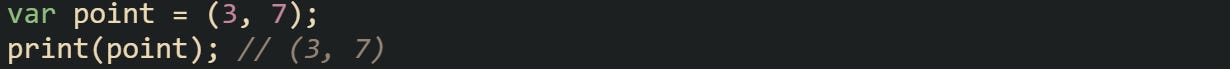

A record is a fixed collection of values held inside a pair of parentheses. Each value has a type, and the number of fields is fixed once the record is created. This means a record that holds two integers is a different type from a record that holds an integer and a string.

The compiler treats this as a record of type (int, int). Records are immutable, so once the values are set, they can’t be reassigned. That immutability helps the analyzer guarantee safe access and keeps behavior predictable.

A big difference between a record and a list is that a list can grow, shrink, or hold values of mixed types unless constrained. A record, on the other hand, is locked in both size and type from the start. That predictability is what makes it a good choice for holding grouped values without the overhead of declaring a class.

Named Fields

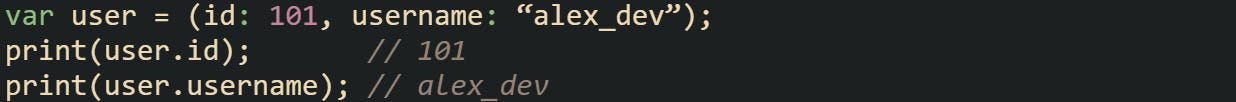

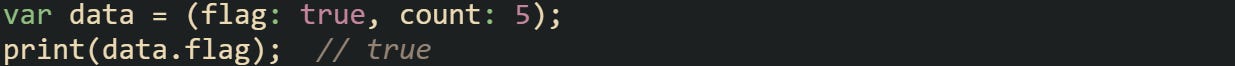

Records don’t have to be positional. They can also carry named fields, which makes the intent much easier to follow in code. Named fields make sense when values have meaning beyond just order.

The compiler treats this as ({int id, String username}). The names become part of the type, so ({int id, String username}) is not interchangeable with (int, String). That type distinction prevents errors where fields could otherwise be mixed up.

Named fields in a record type are written inside braces. The record’s layout is fixed from the start, and you choose the field names and their types when you declare it.

The analyzer knows which fields exist and enforces access by name, so you don’t run into situations where you’re calling for something that doesn’t exist.

Positional Fields

Records with positional fields are accessed by a generated property name that matches their position. These are $1, $2, $3, and so on.

This record has three integers, so its type is (int, int, int). The order matters. A record (int, int) is a completely different type from (int, int, int) because the compiler encodes both the number of fields and their order into the type information.

While positional records work well for basic values like coordinates, it’s easier to use named fields when data has meaning that goes beyond just order. That makes code easier to follow, while positional access tends to shine in quick operations where field names aren’t needed.

How Records Work in the Background

Records are deeply integrated into Dart’s runtime and analyzer. Each unique record type is treated as a distinct entry in the type system. That means (int, String) is one type and (String, int) is another. A record with named fields is a different type and is written as ({String name, int age}). This distinction matters, because it gives the compiler the ability to enforce correctness at compile time and avoid runtime surprises.

The compiler generates a specialized representation for each record type it encounters in code. That representation includes the number of fields, their order, and whether they’re named. At runtime, records don’t turn into ordinary maps or lists. Instead, the runtime has a dedicated way of storing and accessing record data that’s optimized for both speed and safety.

When you access point.$1 or user.username, there’s no lookup cost like there would be in a map. This is possible because the compiler encodes record layouts directly into type information.

Records also benefit from static analysis. If you try to access a field that doesn’t exist, the analyzer flags the error immediately. If you assign the wrong type, the compiler rejects it before the code runs. That combination of compile-time checks and efficient runtime layout is what makes records reliable as a data container.

Pattern Matching in Dart 3

Pattern matching in Dart 3 builds on the introduction of records and adds a structured way to break values apart. Instead of writing chains of if checks or manually unpacking fields, developers can express intent directly in the syntax. This helps the compiler check correctness and makes code both safer and more concise.

Basics of Pattern Matching

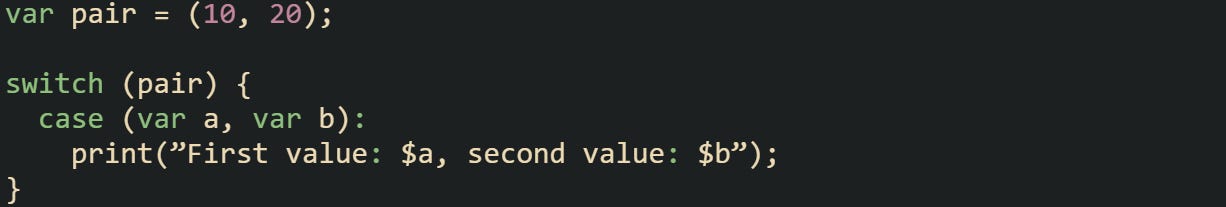

At its core, pattern matching is about describing the structure of a value and binding parts of it to variables. The syntax fits naturally into switch statements, if-case checks, and even simple variable declarations.

The pattern (var a, var b) matches the structure of (10, 20). The compiler confirms that both sides have the same layout and types, then binds the values. If the record didn’t match, the case would be skipped.

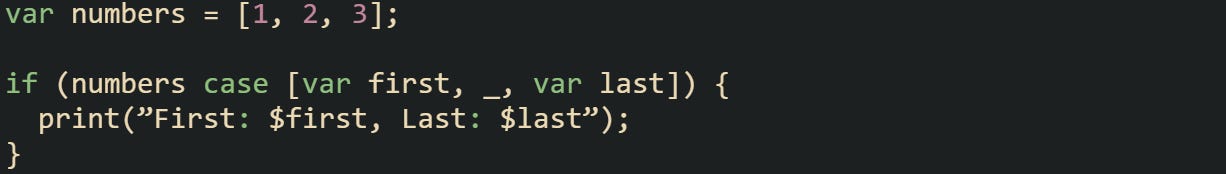

Pattern matching isn’t limited to records. It also works with lists, maps, and enums, which makes it more than a shortcut and establishes it as a built-in feature that ties syntax directly to how data is structured.

This matches a list with three items, ignores the middle one with _, and extracts the first and last values into named variables.

Destructuring Records

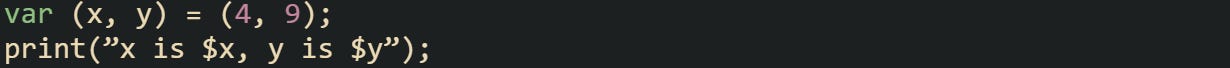

Destructuring means breaking a record into individual variables in one step. This can be done directly in variable declarations or inside control flow.

The pattern (x, y) matches the record (4, 9) and assigns the fields to new variables. The compiler checks that the record being unpacked has exactly two values of compatible types. If you try to destructure a record of the wrong size, the analyzer rejects it immediately.

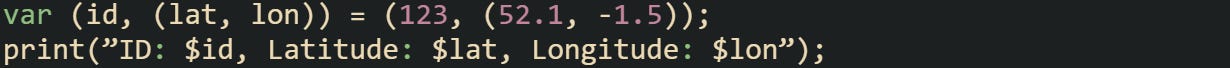

Destructuring can also work with nested records.

The outer pattern expects a record with two fields: one integer and another record. The compiler verifies that the structure matches, and then binds all three values. This kind of nested destructuring saves developers from manually unwrapping values step by step.

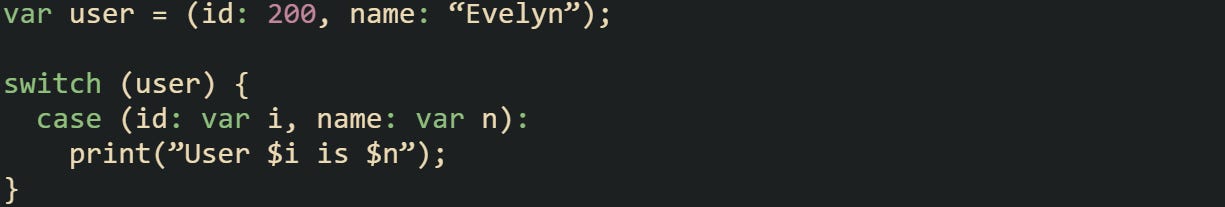

Matching Named Fields

When a record has named fields, patterns can match on those names instead of just positions. This makes intent more obvious in code and reduces the chance of errors caused by mixing up fields.

This explicitly states the field names, and the compiler checks that those fields exist in the record type. If the names don’t align, the code won’t compile. This strictness makes named patterns particularly useful in APIs where the meaning of fields matters.

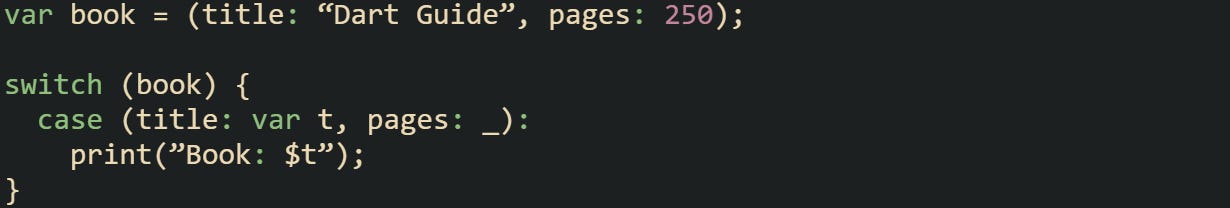

You don’t always need to bind every field. An underscore tells the compiler that you’re intentionally ignoring a value.

In this case, the pages field exists but is ignored, leaving only the title bound to a variable.

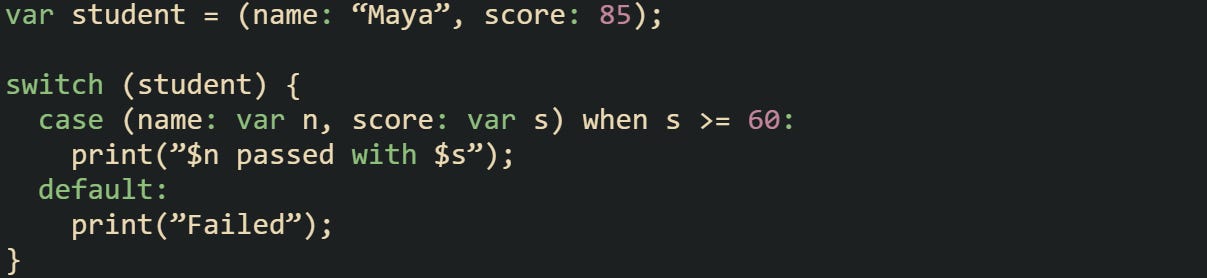

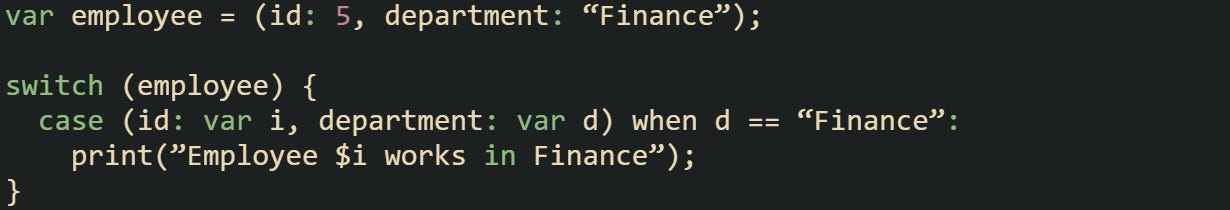

Guard Conditions in Patterns

Sometimes a structural match isn’t enough. You may want to refine it with a condition. Dart patterns allow this with when.

The structure is checked first. If the record matches, then the when condition runs. Only if both succeed does the case body execute.

Guard conditions add flexibility because they let you pair structural checks with logical ones. Without them, you’d have to fall back on nested if statements inside the case body.

This narrows the match further by filtering based on content, not just type and layout.

Mechanics of Pattern Matching

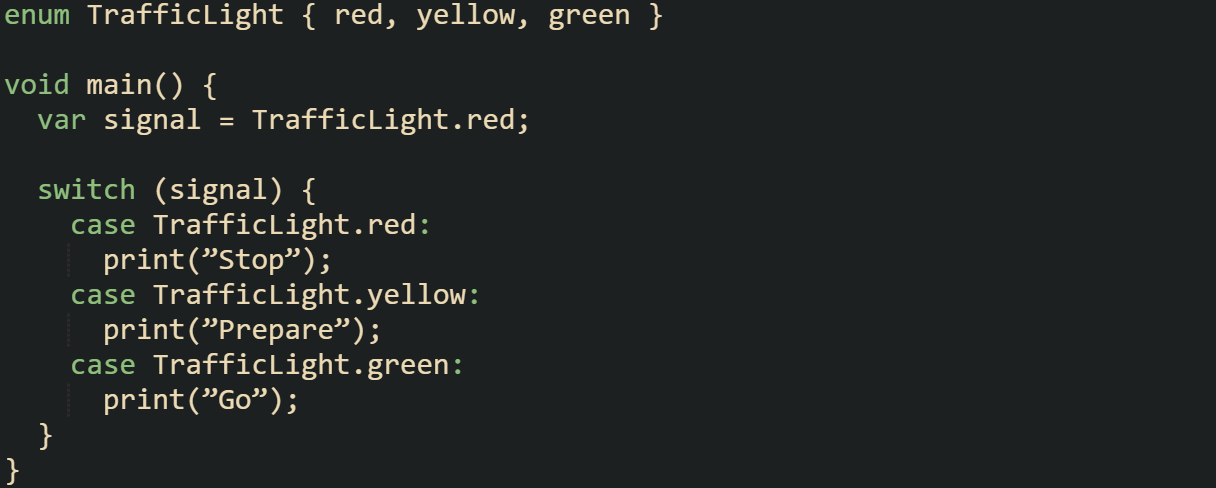

Pattern matching in Dart isn’t a layer of syntax that rewrites into other constructs. It’s tightly woven into the compiler. Each pattern is checked at compile time against the type of the value it matches. For records, the compiler verifies both the number of fields and their types. For named fields, the compiler confirms that the names exist and match exactly.

At runtime, the match process uses metadata stored with each record type. That metadata contains the field count, the order of positional fields, and any names. When a pattern is evaluated, the runtime checks the metadata against the expected layout. If it matches, the values are extracted directly into new variables. There’s no reflection step, which keeps execution predictable.

The compiler here enforces that all possible values of TrafficLight are handled. Leaving one out would result in a compile-time error, which is how exhaustiveness checking protects against missing cases.

Another layer is exhaustiveness checking. With enums, the compiler can verify that every possible value has been covered in a switch. While records don’t have a finite set of variants in the same way, patterns still require full alignment with the declared type. That means you can’t miss a field unless you explicitly ignore it with _.

Pattern matching makes Dart’s type system more expressive by letting structure and meaning flow directly into syntax. The result is code that’s easier for both humans and the compiler to reason about, while still staying tied closely to the mechanics of how values are represented at runtime.

Conclusion

Records and pattern matching in Dart 3 work because the compiler and runtime treat them as deeper parts of the language rather than surface syntax. Records carry strict type information that gives each layout its own identity, while pattern matching builds on that structure with checks that happen before the code ever runs. Exhaustiveness rules and metadata checks at runtime add reliability without creating extra overhead. Combined, these mechanics give developers a way to group values and pull them apart in a style that feels natural to write and is firmly supported by how the language operates behind the scenes.

"That means (int, String) is one type, (String, int) is another, and (String name, int age) is yet another separate type."

Actually, the first and third types there are the same. Two positional parameters, first one String, second one int. If you were trying for named parameters, you need curlies: ({String name, int age}).