RLS, or Row level security, lets a database keep many users or tenants in the same tables while still restricting which rows each session can read or change. Instead of putting every access rule in application code, the database applies extra predicates whenever a query touches a protected table. That arrangement creates a single place for row visibility rules, which matters for multi tenant products, compliance requirements, and shared reporting environments.

Row Level Security Basics

Modern database servers started with permissions that act at the level of whole tables, views, and schemas. Row level security adds an extra check so the server can decide not only which table a session may query but also which individual rows stay visible for that session. RLS can keep several tenants or groups inside shared tables while still keeping their data separated from one another, even when every query flows through the same application logic. Traditional privilege systems answer questions like “can this login run SELECT on table orders”. Row level security adds a second question about row visibility that runs after normal privileges pass. Any session that has table level SELECT still only sees rows that satisfy the row security predicate. That extra filter comes from policy rules that reference both columns on the table and information about the current user or tenant.

What Row Level Security Does

Many developers first meet row level security while working on a multi tenant product where every tenant has its own users, orders, and reports, but all of that data lives in shared tables. Granting plain SELECT on those tables would expose every row to anyone with that permission, so the database needs a rule that trims the result set for each login without asking every query author to remember the right WHERE clause.

Standard SQL permissions treat table access as all or nothing. Either the session has SELECT on a table or it does not, and the server does not inspect which specific rows belong to that caller. With row level security turned on for a table, the server evaluates a policy whenever a statement touches that table. The policy behaves like an extra WHERE expression that must be true for a row to participate in SELECT, UPDATE, or DELETE for that user.

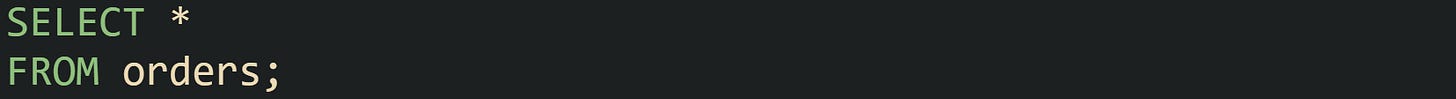

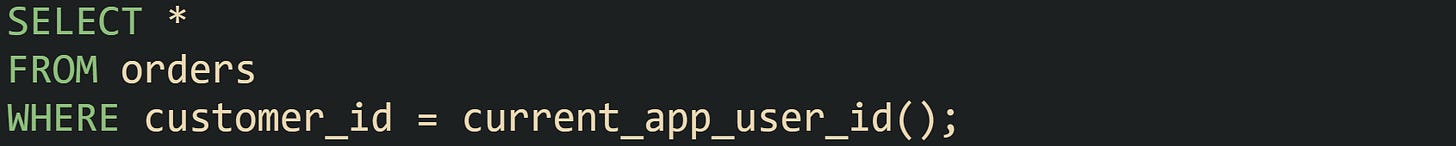

One way to think about this that can help beginners including me when I was learning this, is to think of the database rewriting plain queries so they always include a filter that reflects the current user. Take this example with a shared order:

Ordinary privileges say whether that statement is allowed at all. Row level security then trims rows down to only the ones that match a user or tenant rule. The effect resembles running a second query with a filter that references some identity column.

No real system literally rewrites the text of the query in that way, but the final result set tells the same story. Rows that do not satisfy the policy condition vanish for that session, and aggregates such as counts and sums naturally reflect only the visible subset.

Row level security also applies to write operations in engines that support it. Updates and deletes normally see only rows that pass their policies, so attempts to update someone else’s row in a shared table simply affect zero rows instead of crossing tenant boundaries. Some platforms also enforce checks on inserted rows so new data must satisfy a policy before it enters the table.

Any table can have row level security active or inactive as a feature flag. Databases with built in RLS usually expose a DDL switch that turns it on. A family of systems uses a statement in the same idea:

After that change, every ordinary query that references the employee table flows through the row security machinery, and the table behaves as protected data rather than freely readable data.

Row Level Security Rules

Rules that implement row level security include several moving parts that work in combination during query execution. Treating those parts separately helps explain how databases answer questions about which rows belong to which caller.

Every rule starts with a table that needs protection. Some platforms mark this on the table itself, such as a property that says row level security is active. Others attach the rule through a security object that names both the table and a predicate. In all of those cases, the database records that row level decisions must run for that table in addition to the normal privilege checks.

Predicates carry most of the logic. The predicate is an expression that returns true or false for a row. It may read columns on the row, like tenant_id or owner_id, and values supplied by the current session. Engines that support RLS usually store this predicate as part of a policy definition, which keeps the rule close to the table it guards.

Many systems phrase a predicate directly in SQL. Policies in those systems frequently look like short WHERE clauses that reference both a column and some function call that reflects who is connected.

That single expression can sit inside a policy, a view, or a stored function, yet the core idea stays the same, only rows with a matching tenant id remain visible.

Other vendors let administrators write policy functions in a procedural language like PL/pgSQL, T-SQL, or PL/SQL that return a boolean value or a text predicate. Those functions still end up controlling a WHERE condition, but the extra language features make it easier to handle complex cases, such as administrators who should see multiple tenants or audit robots that should see every row.

Rules also need a scope so the server knows which statement types they apply to. Some policies only apply to reads and leave writes to application code, while others apply to both reads and writes so those queries stay inside the same boundaries. Typical configurations can permit users to read only their own rows yet allow administrators with a specific flag to bypass RLS or rely on a broader predicate.

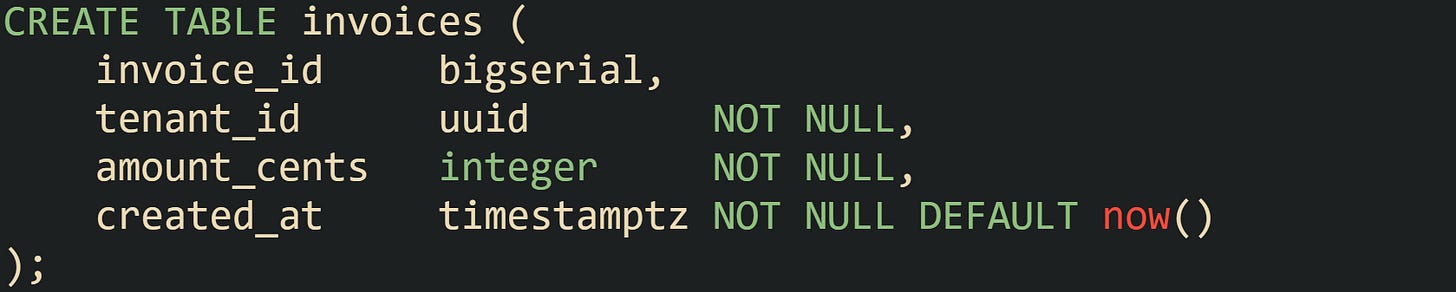

Tenant isolation offers a good starting point when talking about rule pieces. In a shared billing table, every row carries a tenant identifier, and the predicate compares that column to a tenant id stored in session state. Take this example in SQL that focuses on the table structure first:

Row level security never requires a special primary identifier, but many real tables that participate in RLS still have one so updates and joins stay fast and precise.

With a table like that in place, a policy only has to express a comparison between tenant_id and some tenant marker attached to the current session. Different engines spell that policy in their own syntax, yet the logical core is always a predicate along the same lines as the earlier tenant_id expression.

User Context In Session Data

Row level security always needs some notion of who is asking. That identity can come from the database login, a mapped application user id, a tenant id, or a blend of all three. Whatever form it takes, that data has to be available inside the predicate so the database can compare it to the values stored in rows.

Database servers expose several ways to represent identity. Most have a base concept of current user, which refers to the database account behind the session. Many also offer configuration parameters or session context slots that an application can populate just after opening a connection. Those values stay tied to the session and can be read back from inside SQL or policy functions.

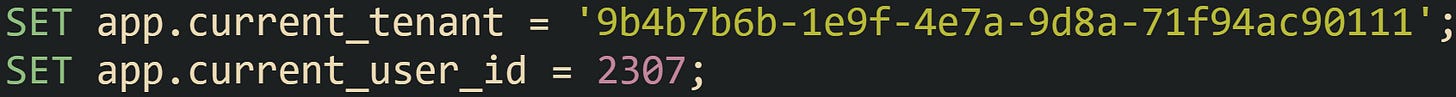

One common arrangement for multi tenant web applications ties HTTP authentication to database context. Middleware code decodes a session token, looks up a tenant id and application user id, and then records those values through small statements at the start of every transaction.

With that information stored as session state, predicates on protected tables can call functions that read those settings. An expression such as tenant_id = current_setting('app.current_tenant') will only pass rows that belong to the current tenant, no matter which query text the application sends later in the transaction.

Vendors ship different tools for this idea, but the template stays similar. Some platforms use special context functions that read from a namespace of session variables, while others rely on explicit session context features that store values under string names and expose them to predicate logic. Regardless of the exact feature name, row level security depends on that bridge between user or tenant identity in the session and matching columns in protected tables.

Systems that lack built in row level security features still rely on user context in a similar way. Views and stored procedures can read CURRENT_USER or other identity markers and use those values inside WHERE clauses that restrict rows. The main difference is that the enforcement lives in views and procedures rather than in a dedicated policy system tied directly to each table.

Row Level Security In Practice

Projects rarely work with row level security as an abstract feature. Real value shows up when a real world database engine takes the general idea of policies and user context and turns that into specific DDL statements, functions, and execution rules. Different vendors picked their own mechanics, but they all revolve around three ingredients. There is a way to mark which tables should be protected, there are predicate rules tied to those tables, and there is some channel that feeds user or tenant identity into those rules at query time.

PostgreSQL, SQL Server, Oracle Database, and MySQL all sit in this picture, although they do not offer the same feature set. PostgreSQL and SQL Server ship built in row level security features. Oracle Database provides Virtual Private Database policies that behave in a closely related way.

PostgreSQL Policies

PostgreSQL keeps row level security turned off for a table until the owner makes an explicit change. That switch prevents surprises on existing schemas. When RLS is off, queries only pay attention to normal privileges such as SELECT or UPDATE on the table. After RLS is turned on, the server evaluates policies for every row that a statement touches, and only rows that pass those policies participate in the result or write operation.

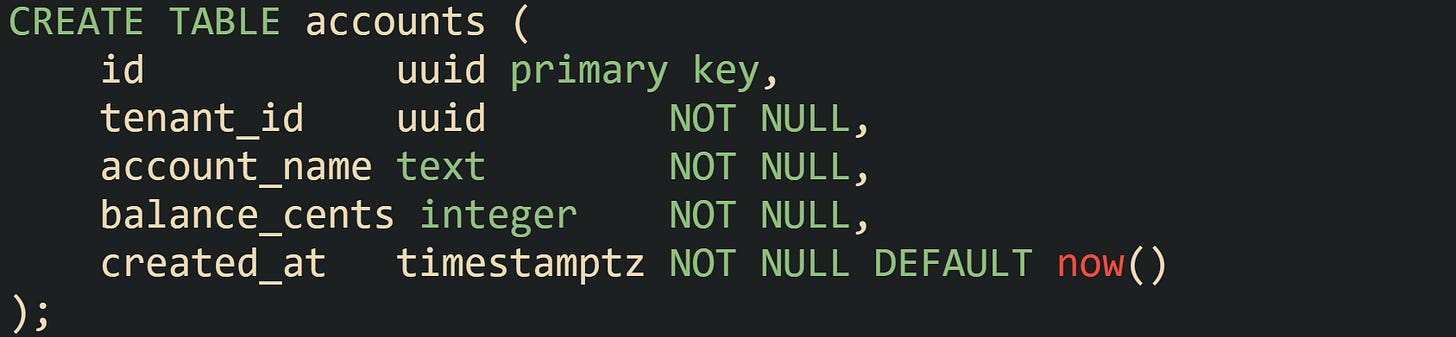

The feature starts with a table. Let’s say we are working with a billing application in Eau Claire that tracks customer accounts in a single shared table with one tenant identifier per row:

PostgreSQL does not treat that table as row protected yet. Turning on RLS takes one DDL statement.

After that change, queries from ordinary roles only see rows that pass at least one policy. When no policy matches, PostgreSQL treats the table as if it had zero visible rows for that user. Superusers and roles with the BYPASSRLS attribute are exempt, and the table owner can bypass RLS as well by default, which helps administrators inspect data when they need to debug policies.

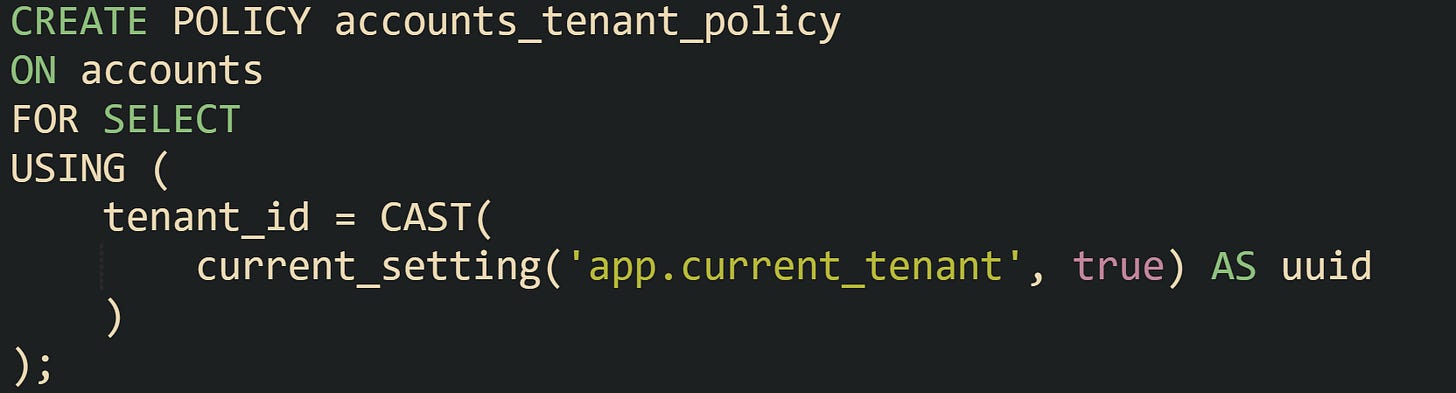

Policies carry the row filter logic. PostgreSQL stores them as named objects tied to a specific table. Policies can apply to all commands or to just one of SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE, and they can be restricted to certain roles.

That policy instructs PostgreSQL to keep rows where tenant_id matches whatever value the application put into the app.current_tenant setting for that session. Any other row in the accounts table behaves as if it does not exist when a SELECT runs through that connection.

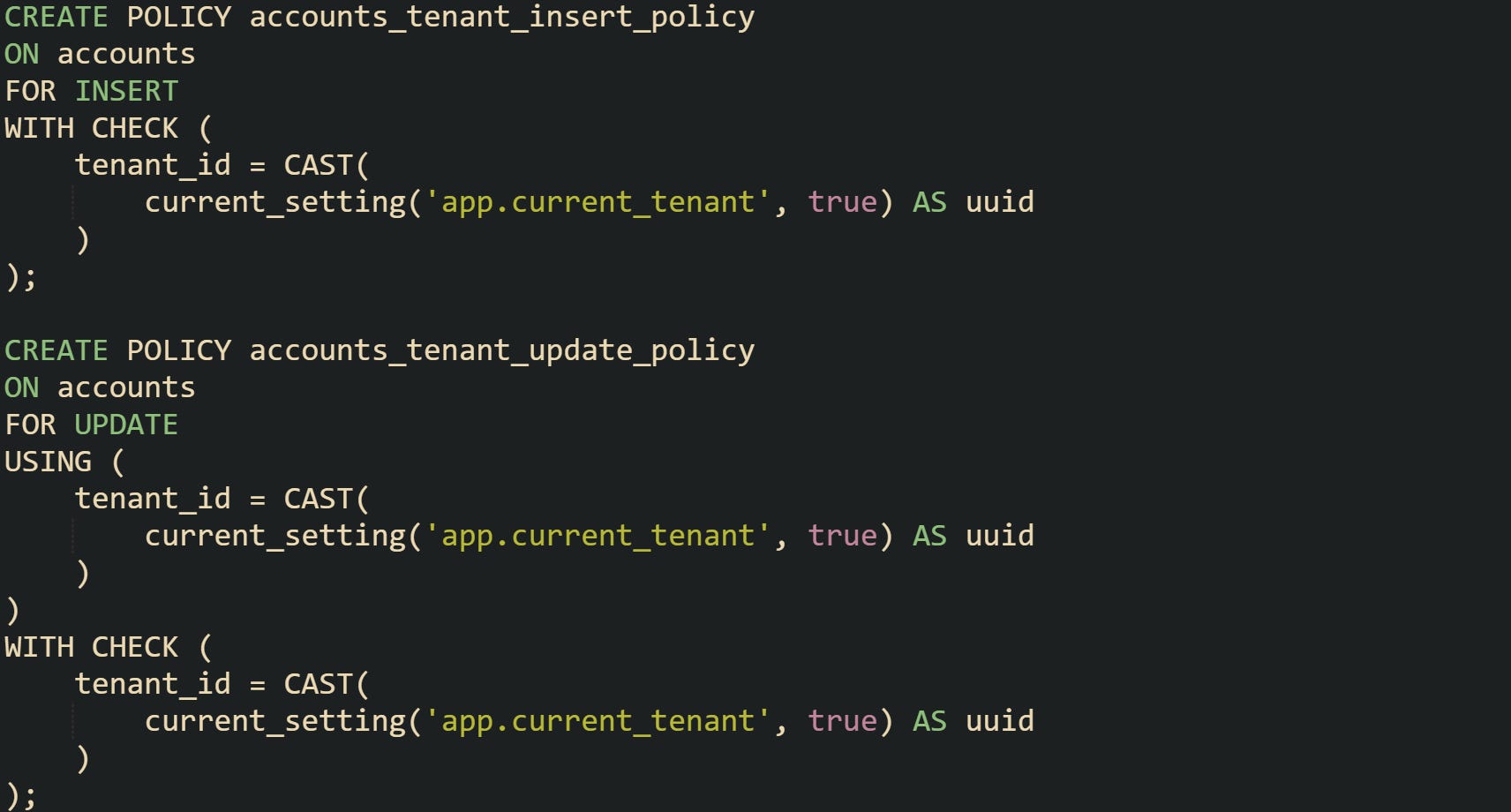

Policies can also check new rows that an INSERT or UPDATE tries to write. The WITH CHECK expression covers this case. If it is absent, PostgreSQL reuses the USING expression, which keeps read and write rules consistent.

With those two policies active, tenants read only their own rows and can only insert or update rows that match the tenant id stored in their session setting. Any attempt to sneak in a row with a different tenant id fails at the database level, even if application code forgets to enforce the rule.

PostgreSQL also distinguishes between permissive and restrictive policies. Permissive policies broaden access, and the server combines their predicates with logical OR. Restrictive policies narrow access, and their predicates combine with logical AND. Each row must satisfy at least one permissive policy and all restrictive policies to appear in query results. This split makes it possible to have a general tenant wide policy, then an extra restrictive policy that hides rows with deleted_at set or that limit certain roles to older data while administrators see more.

SQL Server Security Policy

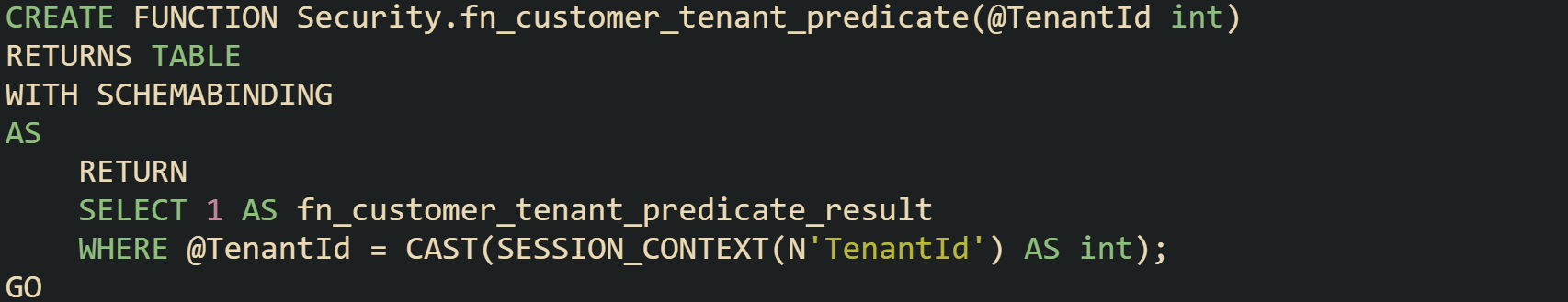

Microsoft SQL Server introduced row level security through a feature that centers on predicate functions and security policies. Instead of embedding the predicate directly into the table definition, SQL Server expects an inline table valued function that checks one row at a time, then a security policy that attaches that function to a table.

Predicate functions live in a schema, just like tables and views. They must use the SCHEMABINDING option so that the engine can reason about dependencies. This next predicate ties customers to their own rows by tenant id:

That function reads from SESSION_CONTEXT, which acts as a key value store bound to the current session. Application code sets the value with sp_set_session_context when a connection opens or when a request starts, and the predicate function compares that stored value to the row’s tenant identifier.

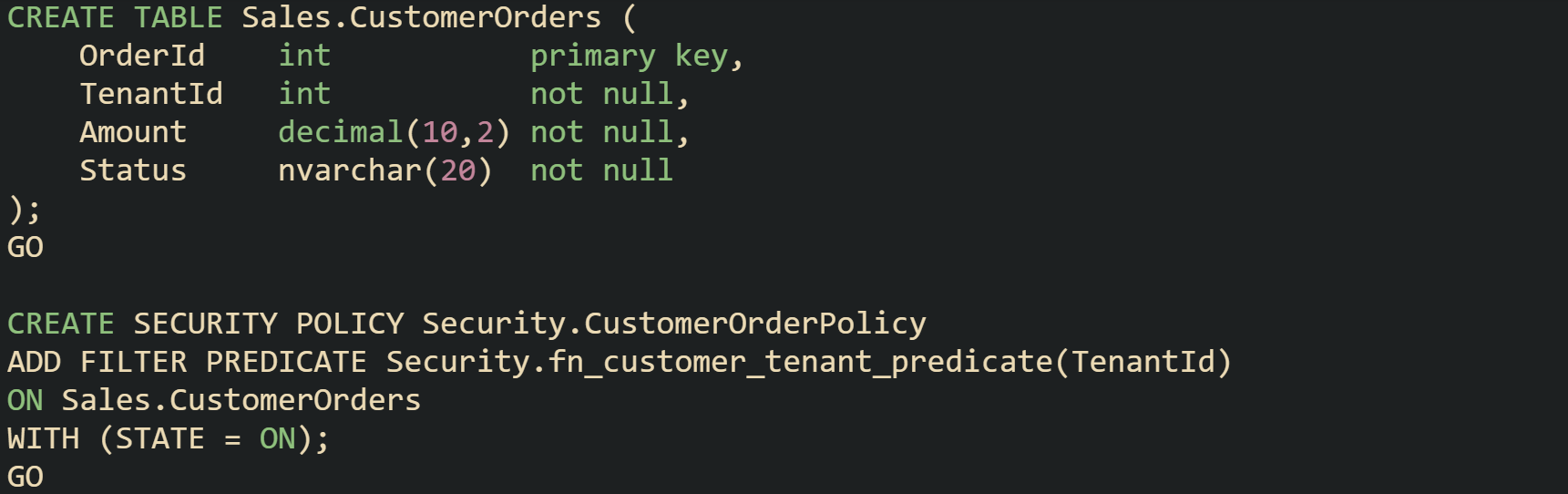

Tables that need row filtering can then reference this function in a security policy:

After that policy is in place, SQL Server calls the predicate for rows touched by SELECT, UPDATE, and DELETE statements. Rows that fail the predicate do not appear in result sets and do not take part in those write operations. The calling code does not need to mention tenant restrictions at all, the policy applies to the table regardless of the query text.

Block predicates extend the model to prevent disallowed writes. A block predicate that targets INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE can stop operations that would have introduced out of tenant rows or modified them in ways that break security rules. Both filter and block predicates share the same table and rely on predicate functions, but they attach to different statement types through the security policy.

SQL Server enforces row filtering through security policies, and it restricts predicates per table by operation. If a table already has a predicate defined for a given operation, trying to add another predicate for that same operation results in an error. Those limits reduce the risk of conflicting logic where one predicate tries to hide rows that another predicate expects to see. Developers working on row level security in SQL Server usually end up with one or two small predicate functions that all related policies share across multiple tables.

Oracle Virtual Private Database

Oracle Database takes a slightly different route with its Virtual Private Database feature, or VPD. Instead of inline functions that return a boolean column, VPD policy functions return a text string that represents a predicate. The engine then appends that predicate to user queries as if they contained that condition from the start.

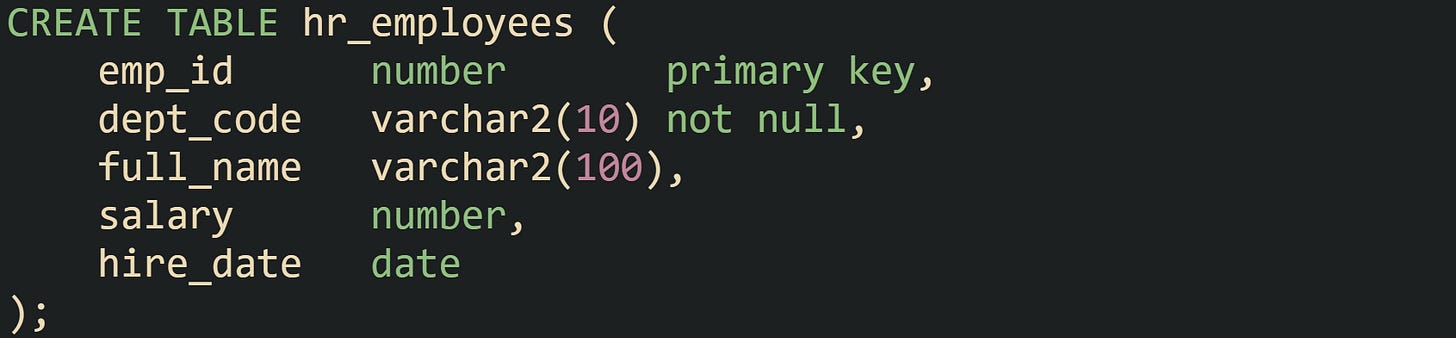

Administration begins with a normal table. Let’s say we are working with a human resources schema named HR that keeps employee data in a single table that serves multiple departments:

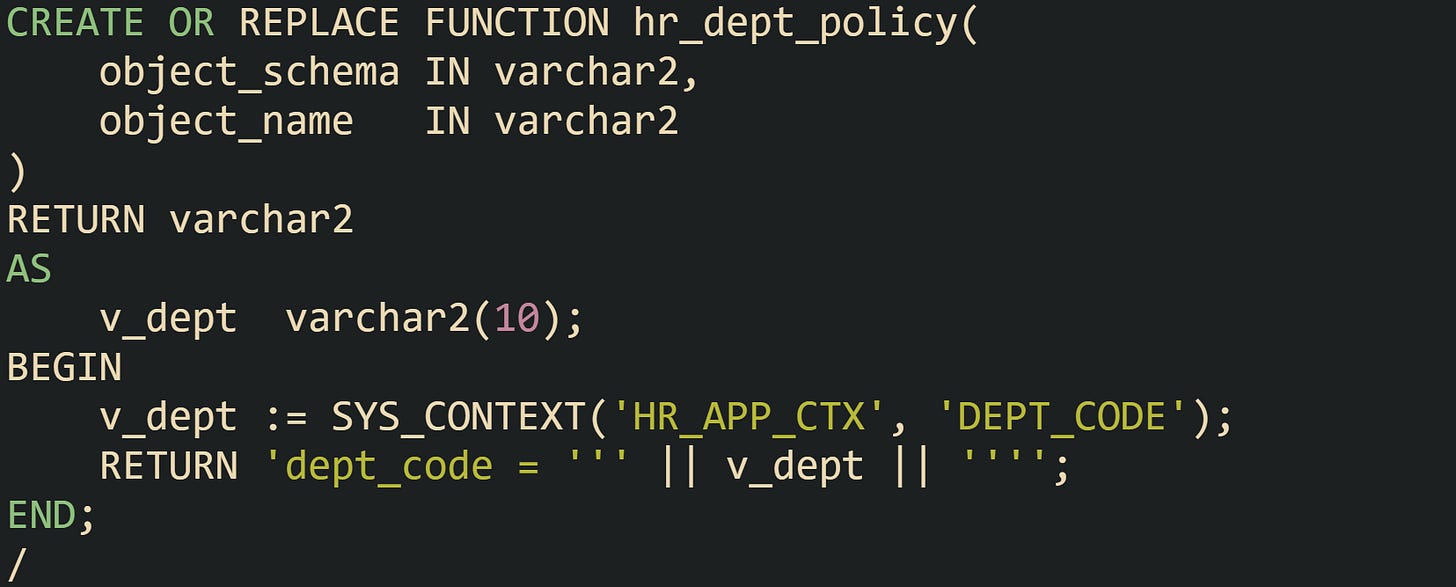

Virtual Private Database relies on the DBMS_RLS package to attach policies. Before that call, a policy function has to exist. That function reads context values, then assembles a predicate string such as dept_code = 'SALES':

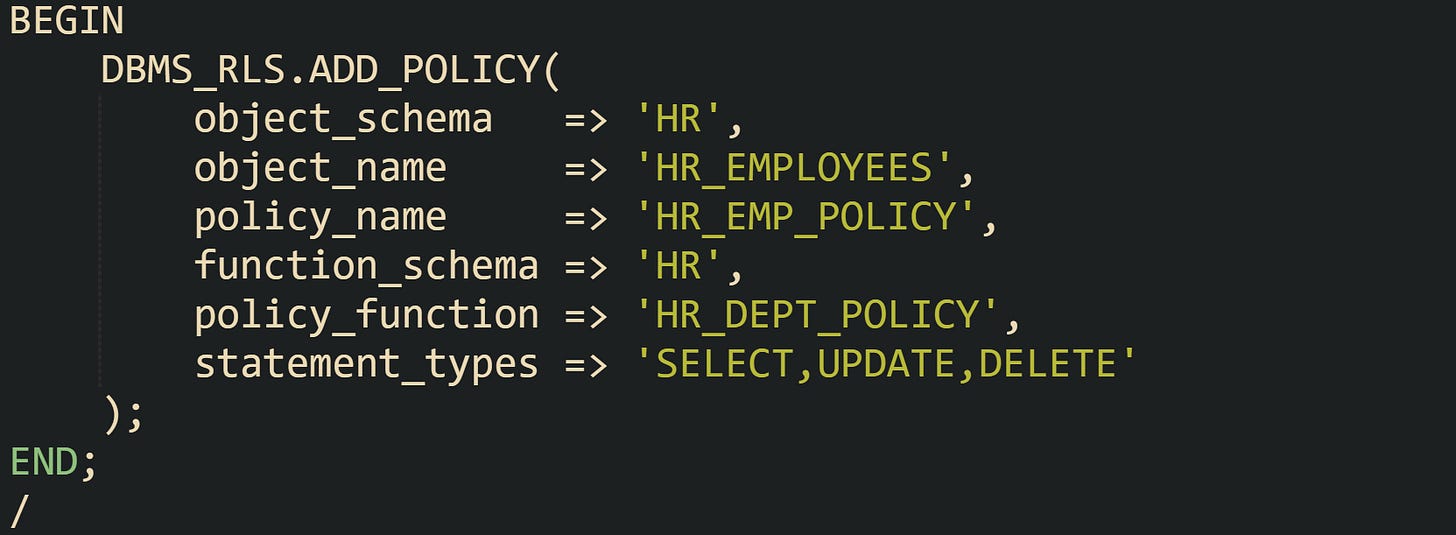

The call to DBMS_RLS.ADD_POLICY links this function to the table:

With that policy in place, Oracle Database consults the HR_APP_CTX context for a DEPT_CODE value during query parsing. The returned predicate string attaches to user queries that reference HR.HR_EMPLOYEES for the listed statement types. Queries that do not mention dept_code in their text still receive that filter at runtime, so users only see rows from their own department. VPD also supports column level policies. Policy rules can apply only when certain columns appear in the query, which helps when columns such as salary need tighter access while columns such as full_name are fine to expose more broadly. In all cases, the engine enforces access by attaching a dynamic predicate to the statement issued against the protected object.

Context values for VPD policies usually come from SYS_CONTEXT. Namespaces such as USERENV expose generic information like session user or client identifier, and custom namespaces created by the application hold values such as department or tenant identifiers. Policy functions stay relatively small because they mainly translate those context values into predicate strings that Oracle attaches to SQL statements.

MySQL Views With Triggers

Standard MySQL editions do not ship a dedicated row level security feature at the server level. Access control still revolves around object privileges, so a user with SELECT on a table can see all rows in that table. Many installations still need finer grained control, so administrators build row restricted access paths with views and grants, sometimes helped by triggers and stored routines.

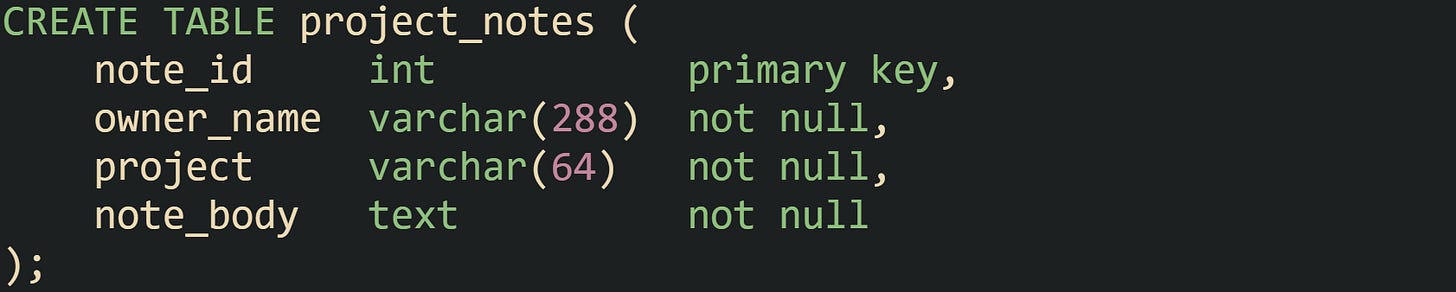

One common arrangement relies on a view that filters rows based on the current MySQL user. The base table may carry an owner column that matches the MySQL account string returned by USER():

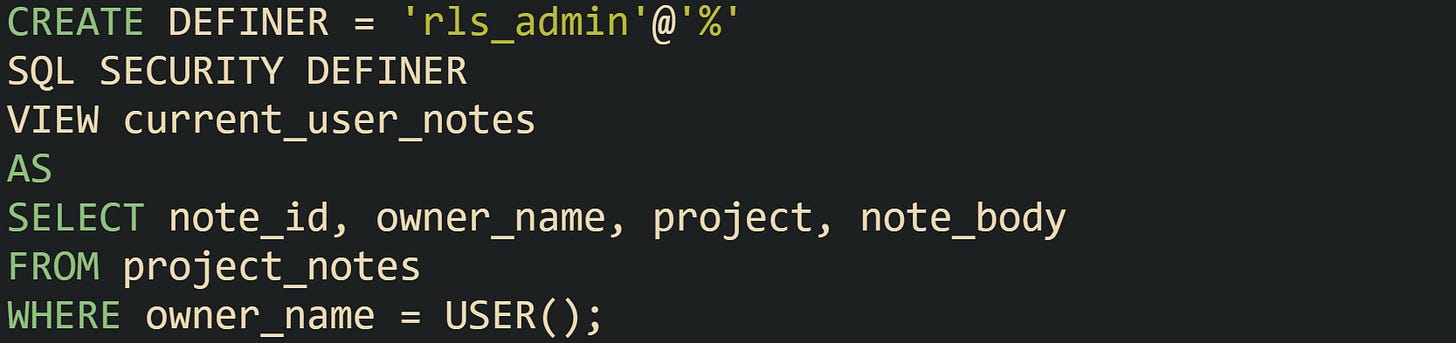

The filtered view then narrows access:

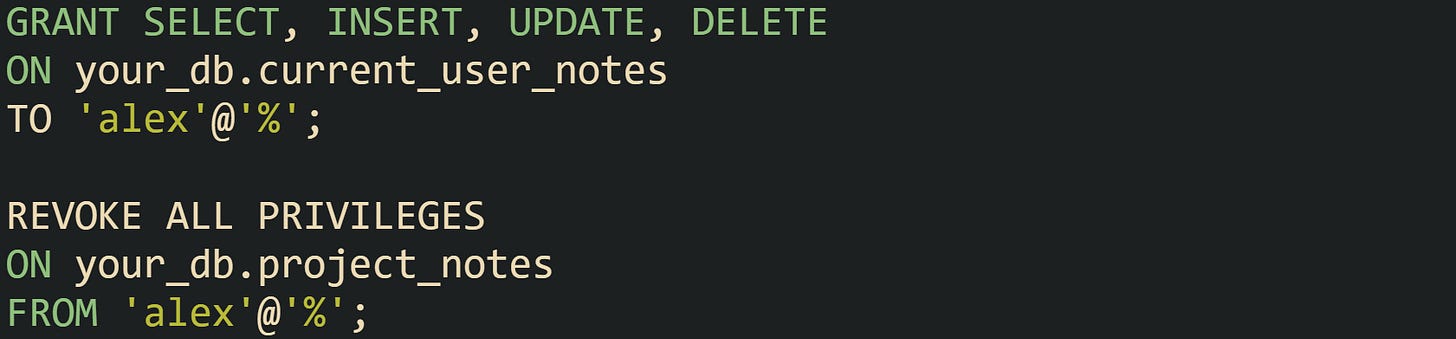

Grants direct users toward the view and away from the base table:

With that structure, the user alex interacts only with current_user_notes. Any query that user sends against the view inherits the WHERE owner_name = USER() filter, and the absence of privileges on project_notes prevents bypassing the filter through direct table access.

Triggers and stored procedures can reinforce that structure for write operations. An INSERT trigger on project_notes can force owner_name to match USER() or SESSION_USER() regardless of what value the client supplied, and an UPDATE trigger can reject attempts to change owner_name to someone else. Some MySQL based systems also centralize writes through stored procedures that check USER() against ownership rules before allowing inserts or updates to proceed.

Cloud platforms built on MySQL, such as Amazon Aurora MySQL and managed RDS for MySQL, document similar setups. Application code connects with accounts that only see filtered views and that rely on triggers or stored routines for data changes. Even though there is no single statement that turns on row level security for a table, the combined effect of views, grants, triggers, and session user checks gives row based isolation that behaves much like built in RLS in day to day work.

Conclusion

Row level security pushes row filtering into the database engine by tying policy predicates to tables and driving those predicates with user or tenant context on every query. PostgreSQL does this with table policies and current_setting, SQL Server with predicate functions and security policies, Oracle Database with VPD functions and DBMS_RLS, and MySQL through views, grants, and triggers around CURRENT_USER. These mechanics define which rows a session can read or modify and keep shared tables isolated while application code continues to send ordinary queries without tenant specific filters in every statement.