Working with databases sometimes calls for looking at every fifth row, every tenth row, or another fixed step through the data. That comes up when sampling records, running checks on queries, or putting together reports where you don’t need to return everything. The way to pull out every Nth row depends on how the database handles row order, sequencing, and conditions during evaluation. Modern SQL provides a few reliable methods, such as arithmetic checks with MOD, analytic functions like ROW_NUMBER(), or filtering tricks that rely on how rows are ordered or indexed.

Methods to Select Every Nth Row

Databases give us more than one path to step through data in fixed intervals. The most direct option is arithmetic filtering, but analytic functions offer more control, and offset tricks can fill gaps where needed. Each of these methods works by leaning on different mechanics inside the query engine.

Filtering with MOD

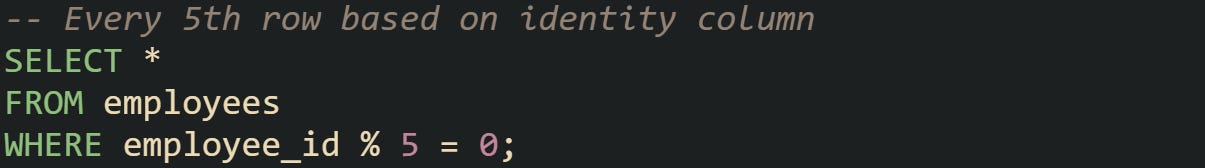

The modulus operator is one of the simplest tools for skipping rows in a consistent pattern. It works by dividing a numeric column by a chosen value and returning the remainder. Rows where the remainder is zero line up with the interval you want to capture.

This works as long as the column used in the modulus calculation holds sequential numbers without unpredictable jumps. A table with an auto-incrementing primary key is a strong candidate, though gaps caused by deletes will affect the spacing.

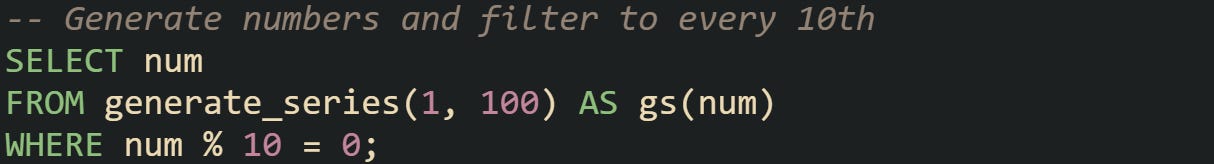

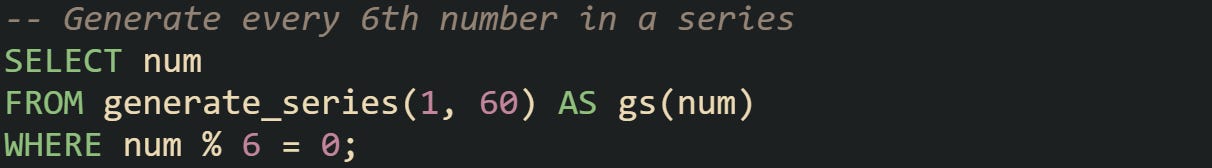

Another variation is to apply the same principle to a generated sequence. PostgreSQL, for instance, can generate a sequence of numbers and then apply modulus to create a filtered set:

That query doesn’t rely on table data at all but reveals exactly how the modulus operator is deciding which rows fall into the set. When applied to table columns, the same logic governs the filtering.

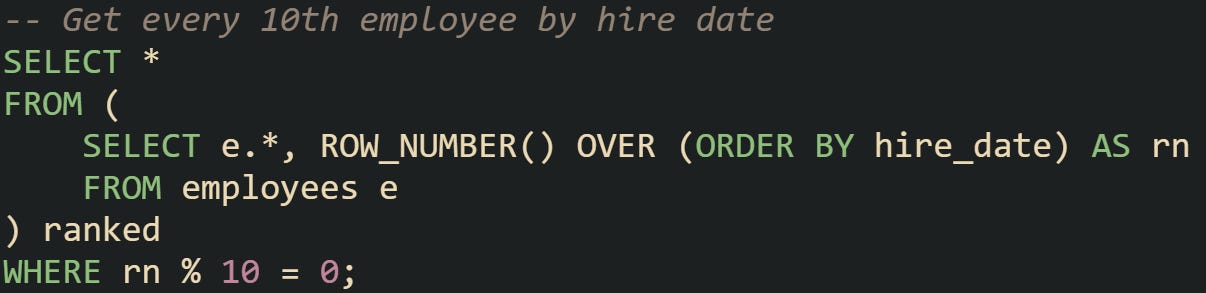

Generating Order with ROW_NUMBER

Analytic functions allow the database to first assign an ordered counter before you apply any filtering. ROW_NUMBER() is the most direct of these functions. It starts at one for the first row in the ordered set, then increments by one for each row that follows. When a counter is available, modulus can be applied without depending on a natural primary key.

This version gives you more control because the sequence respects the order you choose. If you want every 7th order by price, or every 20th user by registration date, the query only needs a change in the ORDER BY clause.

There are also creative extensions of this method. Some databases support partitioning with ROW_NUMBER(), letting you restart the counter within groups. That way, you could sample every Nth row within each department or region.

This makes it possible to grab evenly spaced rows without losing the grouping context, which is something the modulus trick on a primary key alone can’t provide.

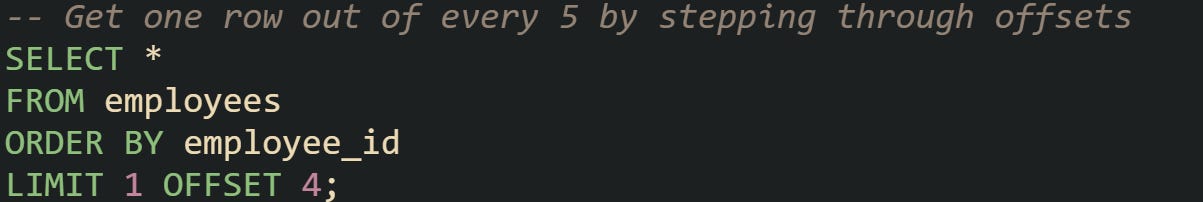

Filtering with OFFSET and Limit Tricks

Some engines allow you to skip rows by stepping through offsets. The idea is less about arithmetic on values and more about controlling which slice of results the query returns. While it doesn’t always replace ROW_NUMBER() or MOD, it can help in situations where you need simple paging.

That only returns a single row, but by adjusting the offset in repeated queries, you can step through the table at intervals. This isn’t as flexible as a single modulus filter, yet it shows how the database supports controlled skipping.

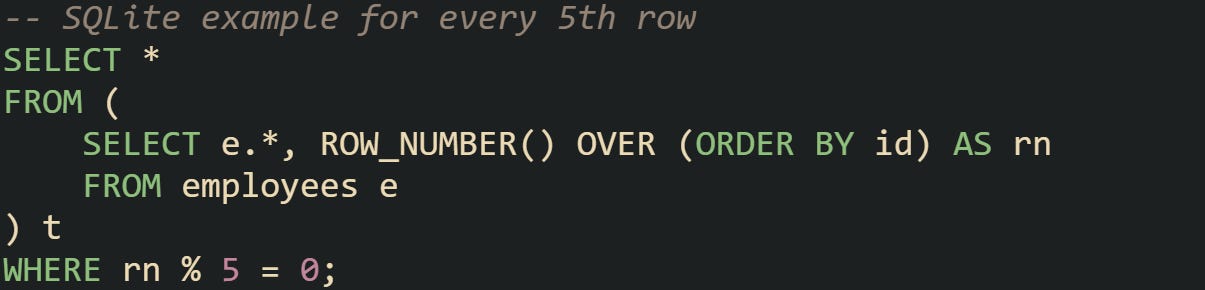

To bridge the gap, you can tie offsets with a row counter. SQLite, for instance, supports ROW_NUMBER() in newer versions, but in older releases developers often combined offsets with subqueries to emulate the effect:

Offset-based filtering is less common for fixed-interval sampling because it tends to favor pagination. Still, the logic that rows are skipped or included based on position in the result set makes it worth noting when thinking through how engines decide which rows qualify.

Practical Mechanics Across Databases

Different database engines handle intervals in slightly different ways. The concepts remain consistent, but the syntax and features available in each product can influence which method is the most practical. Some engines have supported analytic functions for a long time, while others only added them in recent versions. That history explains why you’ll often see different solutions recommended depending on the database.

MySQL

MySQL has long supported the MOD operator, which makes arithmetic filtering a straightforward option. If you have a sequential numeric primary key, you can pull every 5th row without much effort:

This works best when the table grows in order and doesn’t have many gaps. Deletes or skipped values in auto-increment columns can throw off the pattern, though in practice many datasets keep enough continuity that it still works.

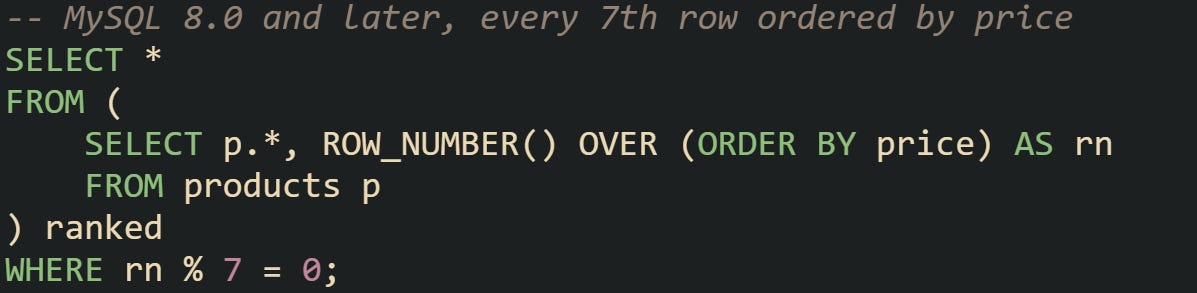

Since version 8.0, MySQL also supports window functions such as ROW_NUMBER(). That opens up more advanced ways to select rows at fixed intervals, based on whichever ordering makes sense for the query.

This method avoids relying on the physical insertion order and instead builds a sequence on the fly, which can be anchored to business logic like price or registration date.

PostgreSQL

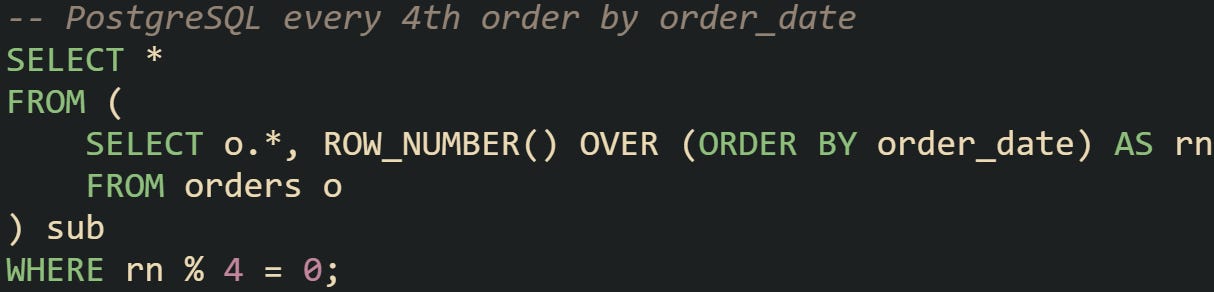

PostgreSQL has strong support for analytic functions, and ROW_NUMBER() is often the preferred tool. Filtering with modulus on that generated counter is reliable and flexible.

The advantage here is that you can define exactly what ordering matters, and the database engine guarantees consistent numbering based on that definition.

PostgreSQL also provides generate_series(), which can act as a test bench for modulus-based queries or to create sample sets directly.

SQL Server

SQL Server offers strong support for window functions, and ROW_NUMBER() is widely used in production queries. When combined with modulus checks, it becomes an effective way to sample rows.

SQL Server’s optimizer is mature enough to handle such queries efficiently, especially when indexes back the ordering column. Arithmetic filtering on identity columns is also possible, but it tends to be less flexible than analytic functions.

This works well in tables where the identity sequence hasn’t been heavily disrupted.

You don’t have to limit yourself to identity columns or names when applying this pattern. Any column that gives a meaningful order can be used, and dates are often a practical choice.

This type of query comes up when you want to sample rows based on a date sequence, such as checking every 12th sale for auditing or quality control. It shows how ROW_NUMBER() can adapt to different ordering criteria beyond identity columns or names, making it useful across many business cases.

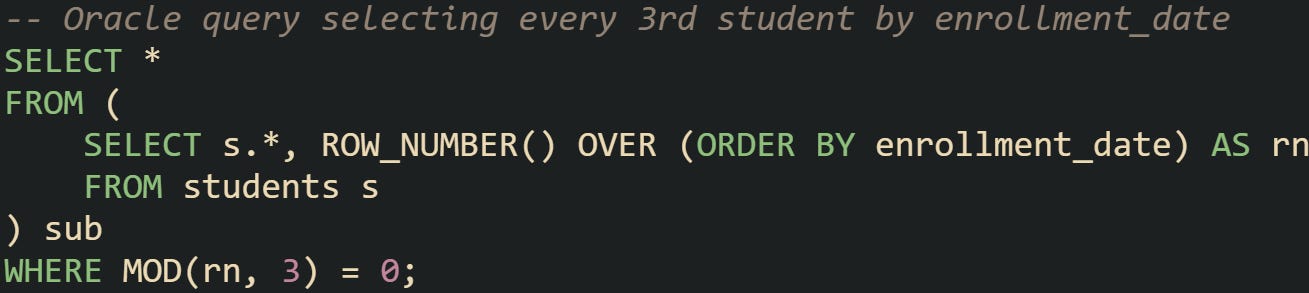

Oracle

Oracle has supported analytic functions for many years, and ROW_NUMBER() remains a standard choice. The database also has ROWNUM, though that feature behaves differently and is applied earlier in query processing. For fixed interval selection, ROW_NUMBER() is more predictable.

Oracle’s analytic engine allows partitioning too, so you can restart the counter for each group, which is helpful in reporting scenarios where you need samples from each category.

That ability to partition makes Oracle particularly flexible when dealing with grouped data.

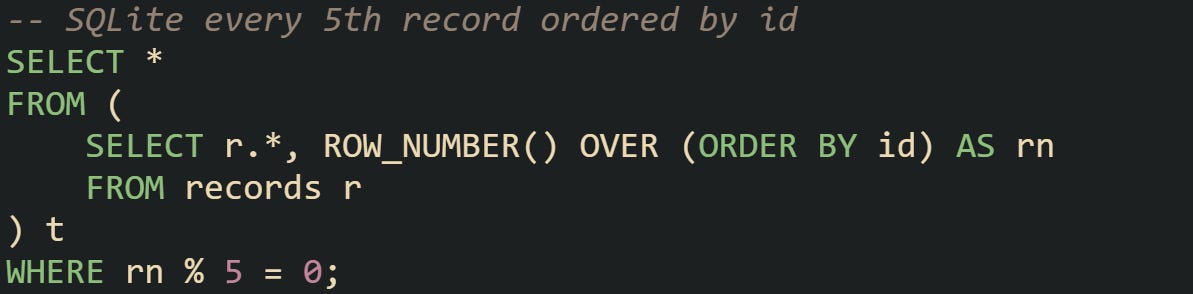

SQLite

SQLite started supporting window functions in version 3.25.0. Prior to that release, selecting every Nth row was tricky and often required creative workarounds with subqueries or manual offsets. With window function support, the process aligns with other modern databases.

For older versions, developers sometimes relied on joins with generated tables of numbers or nested queries, though those solutions were less efficient. Modern SQLite has made this much easier and consistent with what you’d expect across PostgreSQL, MySQL, and SQL Server.

Conclusion

Every method for selecting every Nth row comes down to how the database engine processes order and filtering. Arithmetic checks with MOD lean on numeric columns and are quick when sequences are steady, while ROW_NUMBER() creates its own counter and gives freedom to order rows in any way you need. Offset-based tricks are less flexible but still reflect how engines step through results in sequence. Each technique ties back to the mechanics of numbering rows, evaluating conditions, and applying filters at the right stage in query execution.