Database queries rely on cross table checks in many everyday reports and features. A common need is to ask if a value from one table has at least one matching row in a related table, without returning all columns from that second table. SQL gives several tools for this kind of presence check, and three of the most often used forms are EXISTS, IN, and join based filters. Each form expresses the same idea with different syntax and different effects on readability and performance.

EXISTS for Presence Checks

Presence questions come up regularly in relational databases. You may want to know if a customer has any orders, if a user has at least one active subscription, or if an account has a certain flag set. In many of those cases you only care that a related row exists and you do not want to pull every column from that related table. EXISTS fits that situation well, because it evaluates to true when a subquery finds at least one matching row and false when it finds none.

EXISTS appears in the WHERE clause and wraps a subquery. The subquery usually refers back to the table in the outer query, so the logic is evaluated per outer row, even though many optimizers can rewrite it into a semi join plan. As soon as the inner query finds a match, the EXISTS test turns true for that outer row and the engine can stop scanning further rows inside the subquery.

Basic EXISTS Query for Presence

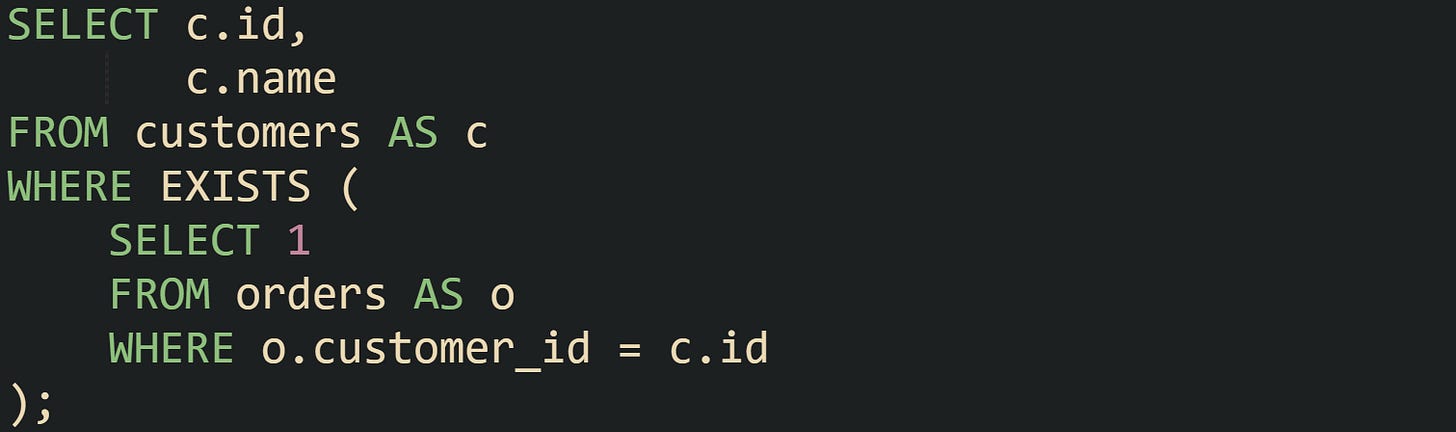

A very common layout pairs a main entity table with a related detail table. One case uses a customers table with id and name columns, plus an orders table that stores purchases and links back to customers through a customer_id column. The goal is to return only customers that have at least one order.

This query walks through customers one by one and, for each customer row, runs the subquery against orders. The condition inside the subquery compares the order customer_id to the current customer id. If the database finds any order with that customer_id value, the EXISTS test becomes true for that customer and the row passes the filter. If the inner query finds no orders, the EXISTS test is false and that customer is excluded.

The constant value 1 inside the inner SELECT has no effect on the result sent to the client. EXISTS only checks whether a row appears, not what that row returns. Many developers use 1, 0, or NULL there, and all behave the same in terms of EXISTS logic.

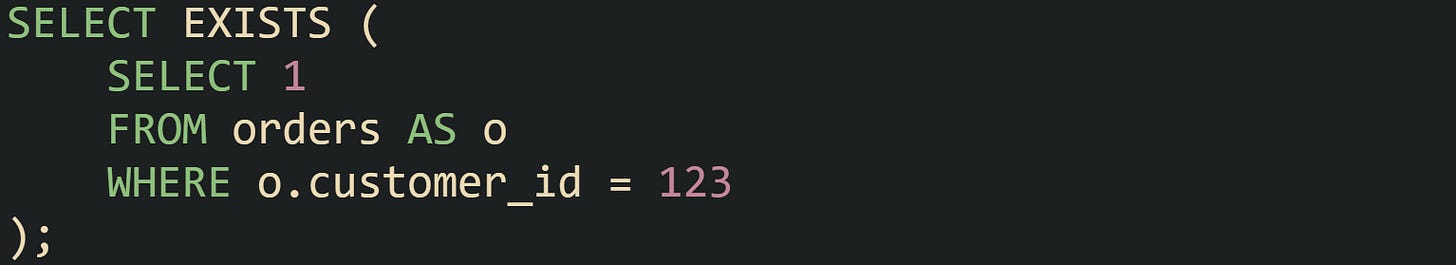

EXISTS can also drive a query that directly answers a yes or no question without listing all matching rows. Some systems allow a top level SELECT that returns a single boolean expression built from EXISTS. With the same schema, a query that asks if a given customer id has any orders at all looks like this in PostgreSQL and some other engines.

That statement produces a single column with a single row, holding true when at least one order matches customer_id 123 and false when none match. Application code can run this query to decide whether to show an account section, an action button, or some other feature tied to order history.

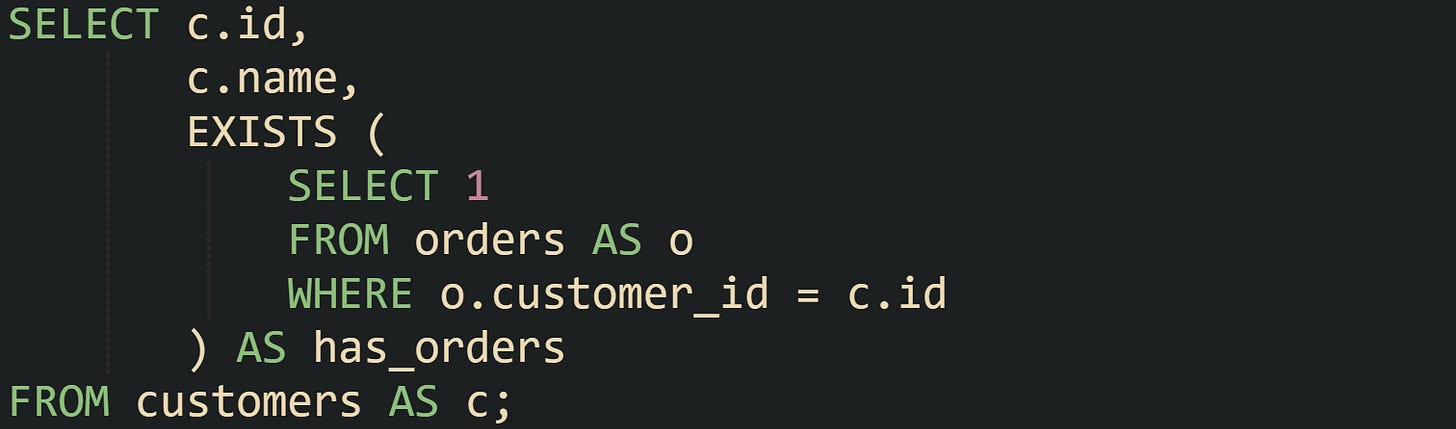

Sometimes you want to keep a list of main table rows and also retain a compact signal about presence in another table without bringing back full detail. In engines that allow EXISTS as a returned expression such as PostgreSQL, MySQL, and SQLite, you can place EXISTS in the select list to do that.

The result for that query contains one row per customer, plus a boolean column named has_orders. For customers that have at least one order row, has_orders is true. For customers without orders, has_orders is false. That single field can drive logic in the presentation layer while the database still avoids sending the entire order history.

These examples share the same structure. The outer query selects from the main table and the EXISTS clause holds a subquery that points back to the outer row through a comparison such as o.customer_id = c.id. The subquery focuses on the related table and its conditions, while the outer query focuses on the columns that flow back to the caller.

EXISTS in Correlated Subqueries

The term correlated subquery refers to a subquery that reads columns from the outer query. EXISTS almost always appears in that form when presence in another table depends on values from the current outer row. The database treats those outer column references as parameters for the inner query.

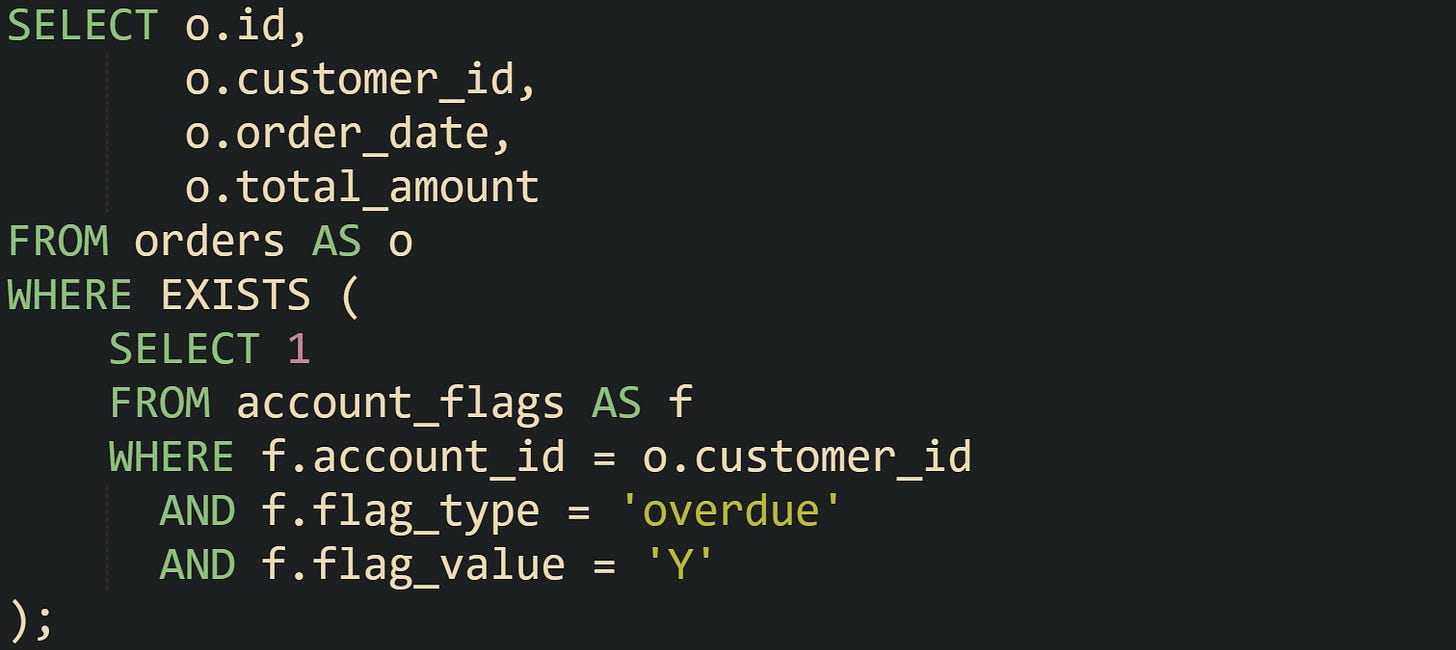

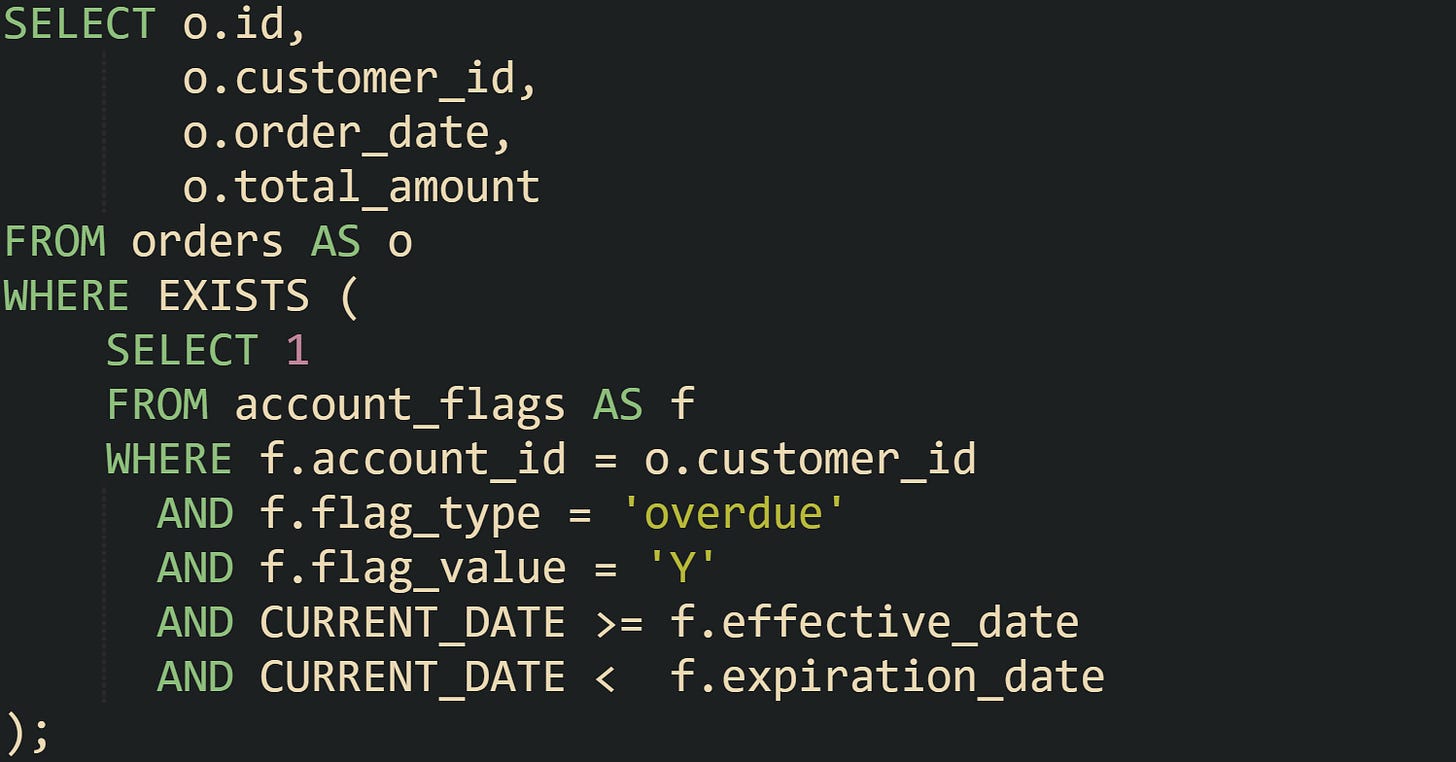

To see that more clearly, lets consider a scenario with an orders table and a table that stores special flags for customer accounts. The flags table holds account_id, flag_type, and flag_value columns, where flag_type describes the kind of flag and flag_value records the state. Suppose overdue customers have a row with flag_type equal to overdue and flag_value equal to Y.

The subquery references o.customer_id from the outer query, so that column becomes part of the execution of the inner query. For each order row, the database treats o.customer_id as a specific value and runs the subquery with that value plugged into the filter on f.account_id. The EXISTS check turns true when there is at least one row in account_flags with matching account_id, flag_type overdue, and flag_value Y.

Many real systems layer more than one condition into that inner WHERE clause. For instance, an account_flags table may timestamp flags with an effective_date and an expiration_date column, and you may want to treat a flag as active only when the current date falls between those values. The presence test then limits itself to flags that are not only present but also active.

With that structure, the database checks for overdue flags that apply on the current date rather than looking at every historical flag. The extra comparisons stay inside the correlated subquery, which keeps all flag related logic in one place and leaves the outer query focused on order columns.

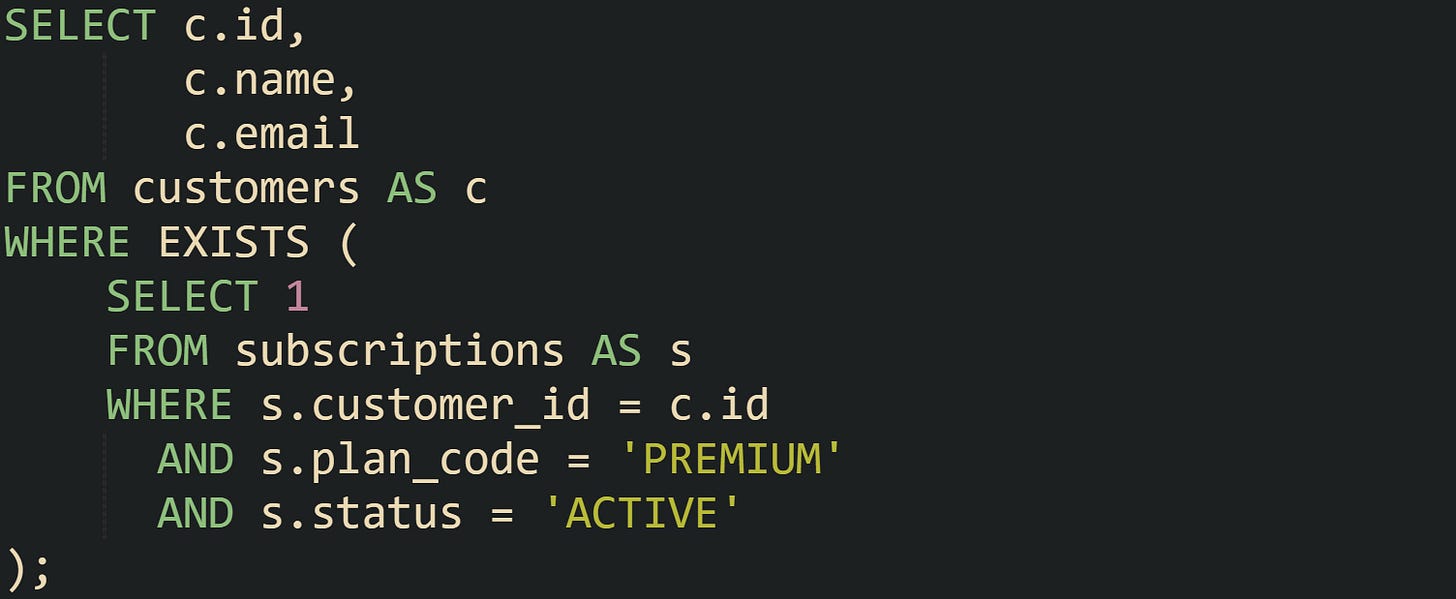

Correlated EXISTS subqueries also play a major part when you want to keep outer rows that have related rows satisfying several conditions at once. Picture a subscriptions table with customer_id, plan_code, status, and renewed_at columns and a customers table with basic account info. One query that keeps customers with at least one active subscription on a premium plan could look like this:

The subquery selects from subscriptions and pulls in c.id from the outer query. That makes the subquery correlated with customers, so it runs in the context of a specific customer id on every pass. The filter on plan_code and status narrows the presence test to active premium subscriptions.

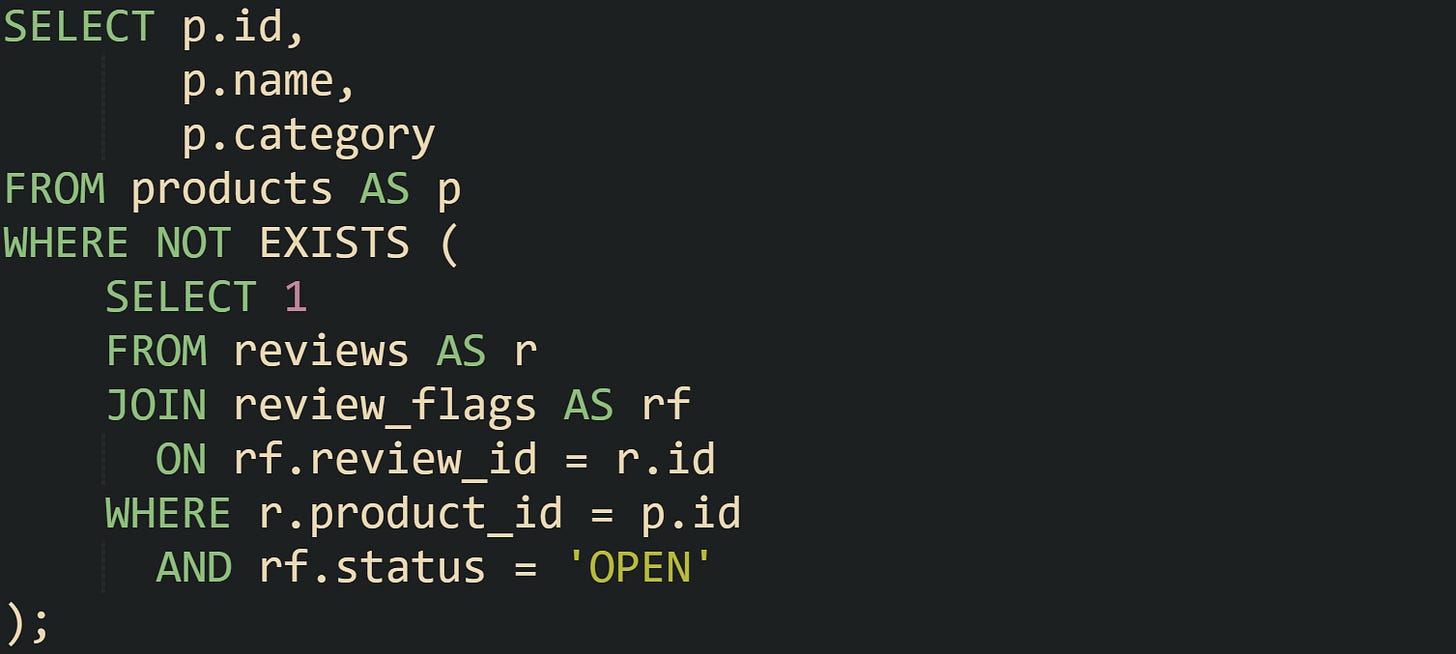

Sometimes the logic goes in the opposite direction and you want rows that do not have a related record. That still falls under correlated EXISTS, but with a NOT operator in front of EXISTS. Suppose there is a table named review_flags that tracks moderation flags for product reviews and you want product rows for items that currently have no flagged reviews.

The subquery joins reviews and review_flags, then links the review back to the outer product row through r.product_id. If any open flag exists for reviews on that product, the EXISTS test inside the NOT becomes true and the outer product row is filtered out. Products that survive this filter have no reviews with open flags.

Across these examples, the shared thread is that the inner query relies on values from the outer query. That link makes the subquery correlated and turns EXISTS into a presence check that depends on the current outer row. The database can use indexes on the foreign key and filter columns like customer_id, account_id, and product_id to limit how many inner rows it inspects for each outer row, which keeps presence checks practical on large tables.

Presence Checks with IN plus Joins

Interestingly, presence checks do not always need a correlated subquery. Many queries only need to test if a value falls inside a set of values produced by another query, or if rows in one table link to rows in another table through a join condition. The IN operator and join clauses give a direct way to express that logic, and database planners can turn both into efficient membership checks backed by indexes. IN reads naturally as a set membership test. Joins make the relationship between tables very explicit, which helps when you also need columns from both sides. Both tools stay focused on the same question of presence, while still avoiding a full read of the related table data when the select list stays narrow.

IN Subqueries for Lists of Values

The IN operator compares one expression against a list. That list can be a literal list such as ('CA', 'WI', 'TX') or a result set produced by a subquery. When the list comes from a subquery, the usual presence check says that a row should pass the filter when some column value exists in a set of values pulled from another table.

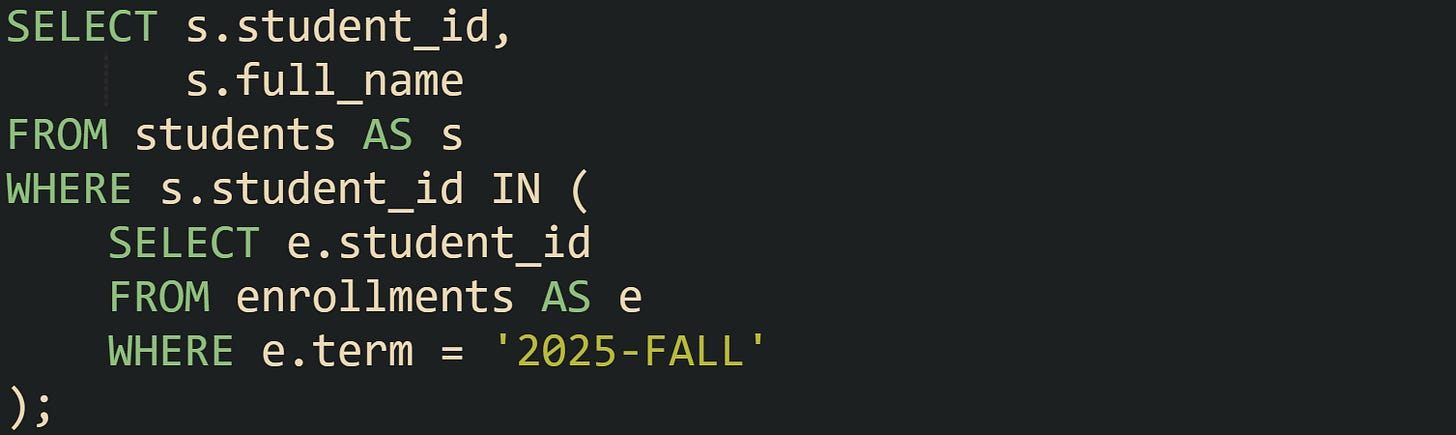

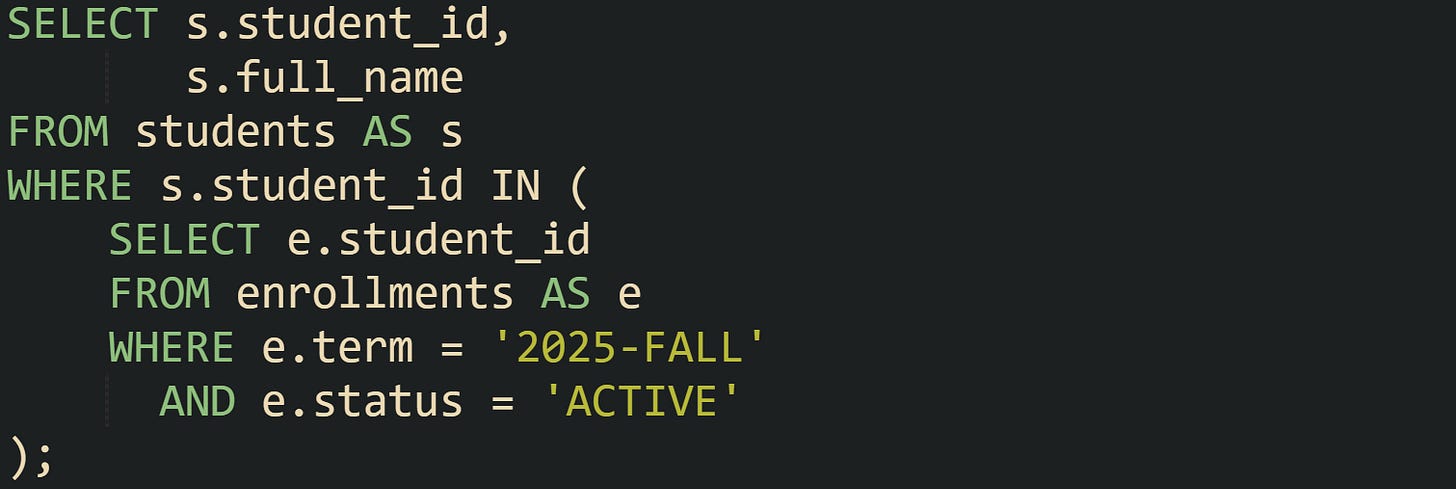

Take a registration database with two tables. One table named students holds student records with columns such as student_id and full_name. Another table named enrollments stores course registration rows with student_id, course_code, and term. To find students who have at least one enrollment in a given term, an IN subquery fits well.

For this query, it builds a set of student_id values from enrollments for the term 2025-FALL and then keeps only those student rows whose student_id appears in that set. Behind the scenes, the planner can use an index on enrollments(student_id, term) to satisfy the inner filter and can also use an index on students(student_id) to probe the student table efficiently.

IN also combines well with additional filters on the inner query side. Suppose a system tracks a status column on enrollments with values such as PENDING, ACTIVE, and CANCELLED. A query that keeps students who have at least one active enrollment for that term only needs a small adjustment.

Now the membership check is based only on active records. The set built by the subquery holds only student_id values from rows that match both the term and the status, and the outer query stays as a simple membership test.

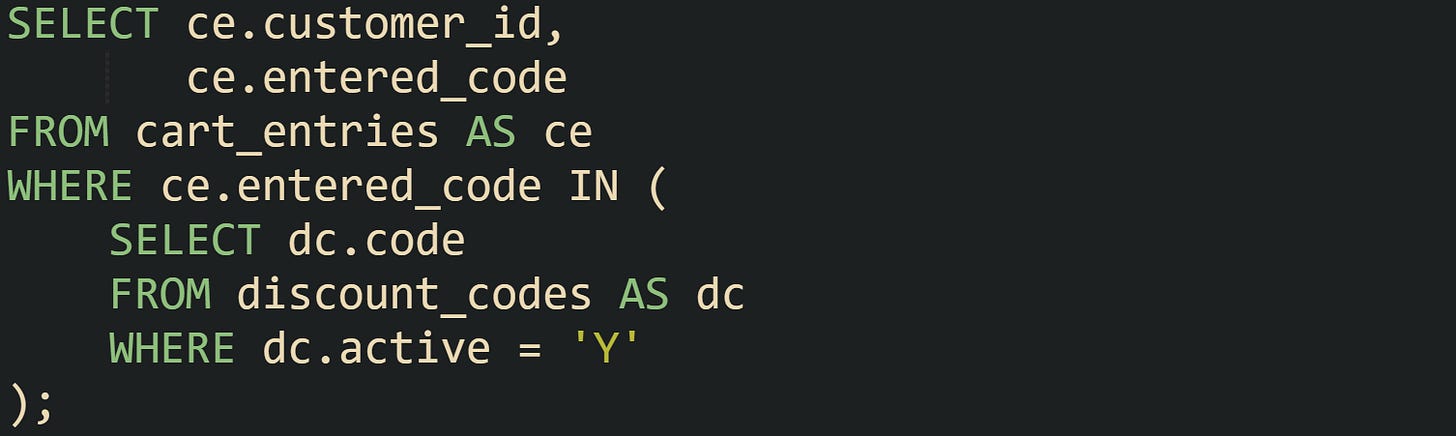

Presence checks with IN do not have to link primary keys. They can also match on business values that appear in more than one table. Picture a table named discount_codes that lists all codes that are currently valid, and another table named cart_entries that records codes customers typed into a cart.

This query keeps only those cart entries where the entered_code is part of the live set in discount_codes. No columns from discount_codes appear in the outer select list, so the query still works as a presence check. Validation logic in application code can call this query to decide if a code is acceptable without fetching every attribute of that code.

Handling NULL in IN Checks

IN interacts with NULL in a specific way due to three valued logic in SQL. When the value on the left side of IN is NULL, the result is unknown rather than true, even if the list contains only NULL values. When the left side is non NULL and no list value matches, the result is false only when the list contains no NULL values. If the list contains at least one NULL value and no comparison is true, the result is unknown. These rules matter when you run presence checks on columns that can contain NULL.

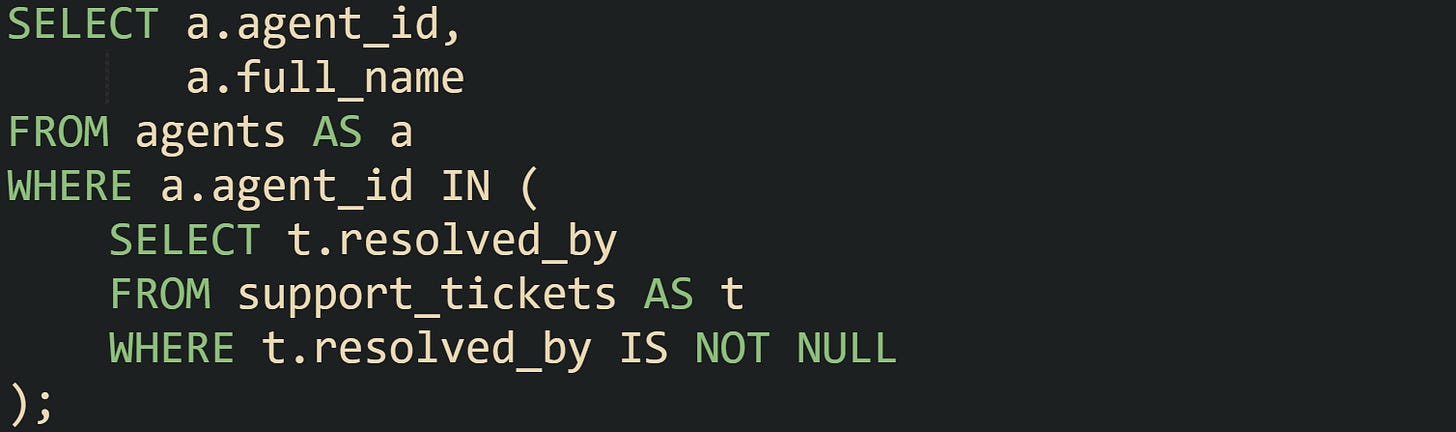

Lets imagine we are working with a customer support system with a users table and a support_tickets table. The support_tickets table includes a resolved_by column that stores the agent id from a table named agents, but sometimes that column is NULL for unassigned tickets. To find agents who have resolved at least one ticket, an IN subquery might look like this.

The filter t.resolved_by IS NOT NULL inside the subquery protects the IN list from NULL values. Without that condition, NULLs in the inner result would not make the comparison true, but they would still participate in the three valued logic rules, which can make reasoning about the expression more confusing. Many schemas avoid that risk by marking foreign key columns as NOT NULL when business rules support that choice.

Presence checks with IN also need care when the left side expression can be NULL. Suppose some agents do not yet have a stable identifier, so agent_id can be NULL for newly created rows. In that case, a.agent_id IN (subquery) evaluates to unknown when agent_id is NULL, and those rows drop out of the result because WHERE only keeps rows where the condition is true. That behavior is correct in many systems, but it is based on a rule about NULL handling rather than ordinary equality.

When both sides can contain NULL, many developers switch to EXISTS and write a correlated subquery, because the inner WHERE clause can test NULL and non NULL values with explicit conditions. That keeps the behavior in line with what the business rule describes, without relying on subtleties of three valued logic.

Join Based Presence Queries

Joins can express presence checks by linking tables directly in the FROM clause, then using DISTINCT or filters to keep only the main rows of interest. Inner joins keep rows that have at least one match on the join condition. Outer joins can keep both matching and non matching rows and then a WHERE clause can pick out the group that matters.

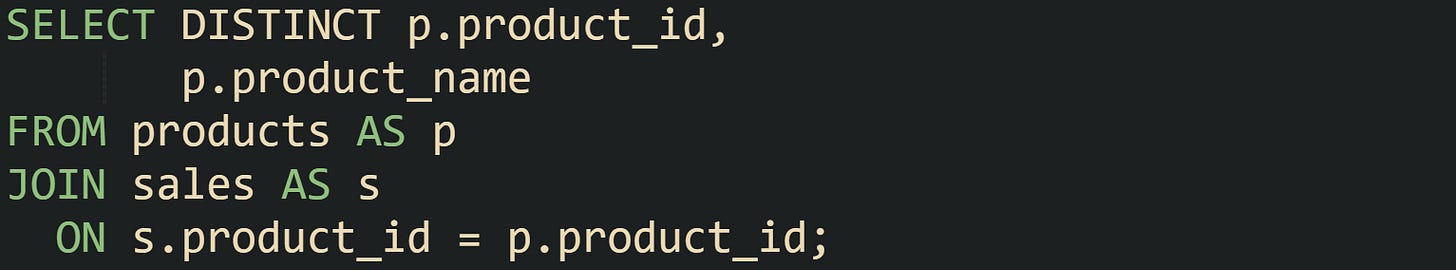

Take a retail database with a products table and a sales table. The sales table stores one row per sale line, including a product_id that references products. To list products that have at least one sale, an inner join does the job.

The join condition links sales rows to products rows. Without the DISTINCT keyword, a product with many sales would appear many times in the result, once per matching sale line. DISTINCT collapses those duplicates so that each product appears only once. A query planner can use an index on sales(product_id) to match rows from the sales table to products efficiently.

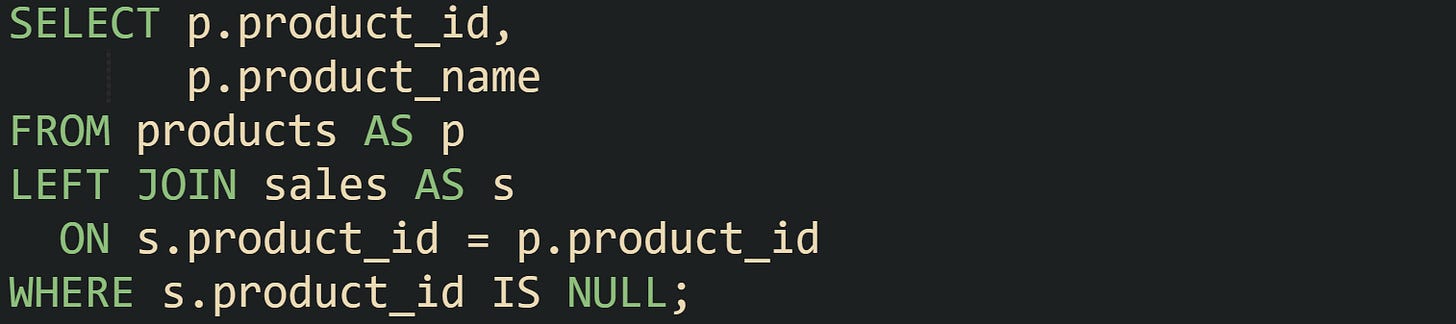

Presence checks with joins also cover the reverse case, where the goal is to find main rows that do not have a match. LEFT JOIN keeps all rows from the main table and fills columns from the joined table with NULL when there is no matching row. WHERE clauses that check for NULL on a column from the joined table then filter down to non matching rows.

Here, this query returns products that have no sales recorded. The LEFT JOIN keeps every product, and rows without a match in sales get NULLs in the s.* columns. The WHERE clause keeps only those rows, which means the final result lists products that have never been sold.

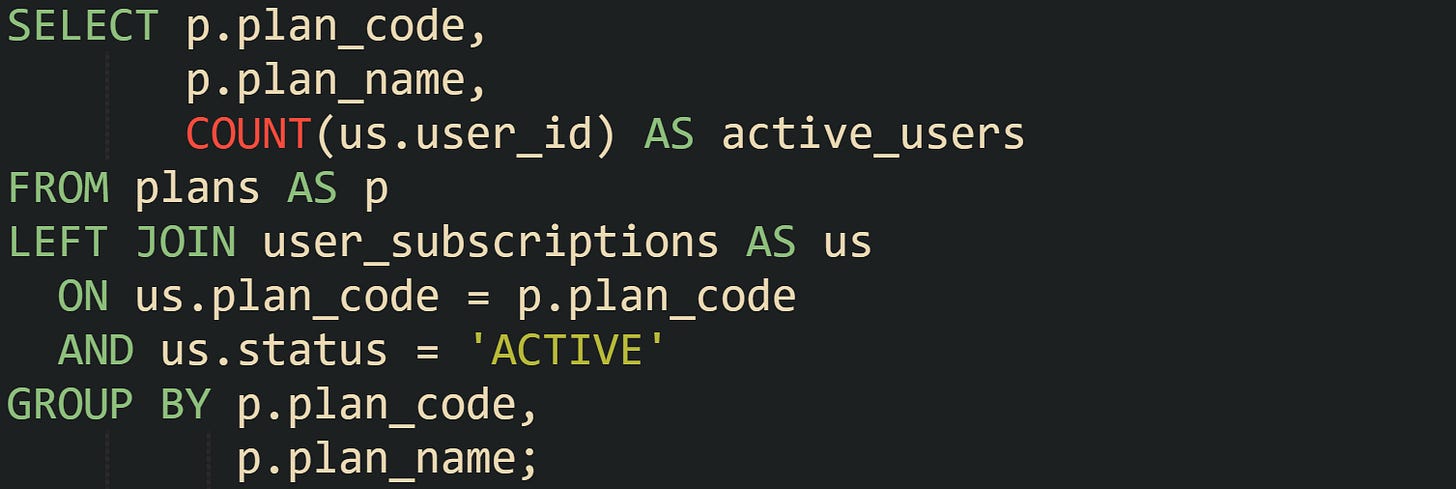

Join based checks show up frequently in reporting queries where more than presence is needed. Suppose a system tracks subscription plans in a plans table and active subscriptions in a user_subscriptions table. To list plan names and the number of active users on each plan, you can use a join with an aggregate.

The LEFT JOIN keeps all plans, even when no users have that plan. The join condition includes a filter on us.status, so only active subscriptions contribute to the COUNT. Presence checks sit inside that aggregate, because the count for a given plan will be zero when no active subscriptions exist, and positive when one or more active subscriptions match.

Conclusion

EXISTS, IN, and join based filters all address the same need of checking if related rows are present while returning only the columns you care about. EXISTS treats the subquery as a yes or no test and can stop reading inner rows as soon as it sees a match, which matches well with correlated checks tied to a single outer row. IN treats the subquery result as a set of values, so the database can compare one expression against many candidates and rely on indexes or hash structures to keep that membership test efficient. Joins express presence through direct links between tables, and with DISTINCT, aggregates, or NULL checks after outer joins, they can report which rows have matches, which ones do not, and how many related rows exist. Taken as a group, these three tools give SQL a consistent way to handle presence checks without fetching full detail from related tables.