Text fields that squeeze several values into one place tend to slow down analysis, yet this pattern still turns up in logs, imports, and older tables. Packed text needs to be broken into rows so every value lands in its own spot, which brings the data back to a form that plays well with normal queries. Modern engines give you ways to pull that apart through functions, table constructors, and set returning tools. The idea behind them stays mostly the same across vendors, though the names and entry points change a bit from one system to the next.

String Split Functions

Work with comma separated values tends to show up in all sorts of places, from import files to event logs. Engines have stepped up over the years and now ship tools that peel those strings apart without a pile of custom loops or client side parsing. The broad idea stays steady across platforms. A value gets broken into pieces, those pieces turn into a list, and the list expands into rows that behave like any other table source. Vendors package this in their own way, and that gives you a few different shapes to work with.

Built In Split Functions

Vendors that ship a direct split function remove a lot of friction when all you need is a clean row set from a comma separated value. SQL Server has leaned on STRING_SPLIT for years. PostgreSQL pairs string_to_array with unnest, though some newer client libraries also wrap this pair for a more direct split. MySQL has moved toward JSON_TABLE for structured expansion, while Oracle keeps REGEXP_SUBSTR for string slicing when the separator is stable.

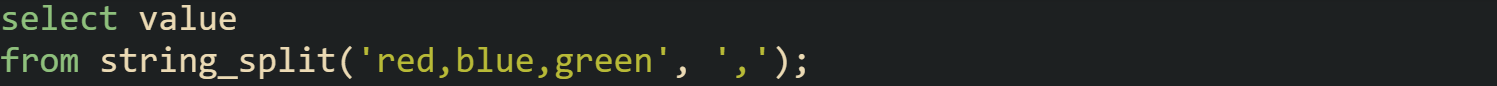

SQL Server keeps things short. The function reads a value, breaks it apart on a separator, and returns a table with one column called value.

Each color lands in its own row, which gives you a small and predictable result.

PostgreSQL works through an array. Text is split into an array through string_to_array, and unnest expands that array. Some find this pattern clearer because it matches the way PostgreSQL thinks about lists.

Rows come back in the order they appear in the array. That ordering depends on the text provided, which helps when downstream logic expects a stable sequence.

MySQL leaned heavily on regular expressions for a long run, though JSON_TABLE has grown into a strong option whenever the text can support a quick conversion to JSON format. The constructor is simple once the quotes wrap properly.

Each cell in the JSON list turns into a row. Workflows that rely on user generated tags or feed imports from different systems tend to benefit from this technique.

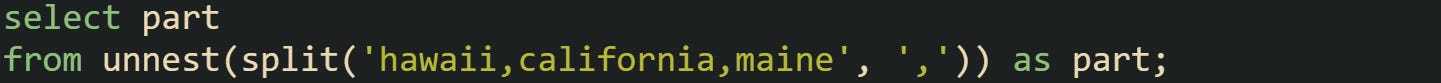

Oracle continues to support REGEXP_SUBSTR for text slicing. It works well for steady separators even though it doesn’t run as fast as a built in table function. Oracle also pairs this with hierarchical queries.

Level counts from one and up. Each match feeds the next row until there’s nothing left to match.

Pattern Based Splitting

Some workflows run into separators that vary or text fields that contain stray spacing. Pattern tools give you more room to deal with those cases. Engines that support recursive queries or hierarchical expansion allow you to peel off one match at a time until the string is empty.

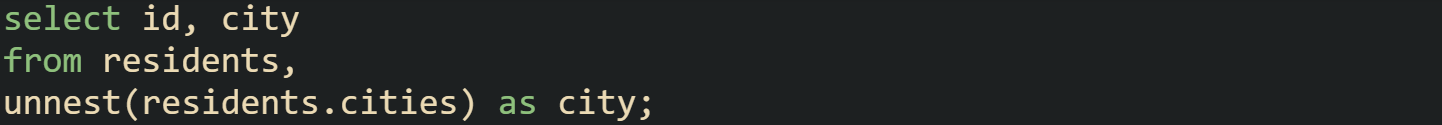

MySQL supports recursive queries in modern versions, which makes pattern extraction feel natural after the core regular expression is set.

That pattern trims stray spaces and keeps only the fragment between separators. Workflows built around product codes, tag lists, or log labels tend to rely on this shape because the spacing around a separator can shift.

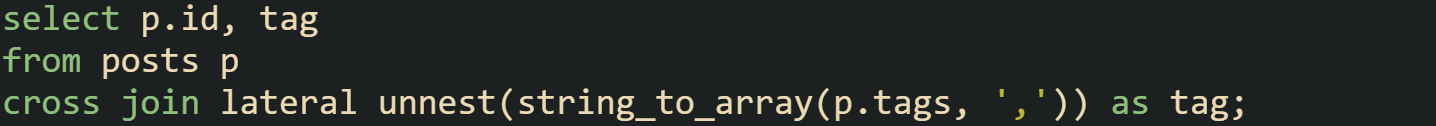

Oracle handles this in a similar way with hierarchical queries, though many teams fall back to a simple loop when the pattern is stable. Pattern tools in Oracle accept capturing groups and repeat counts, so you can pull fragments from text that carries multiple potential split points.

Each term flows into its own row, and the extra spacing around semicolons doesn’t disrupt the matches.

PostgreSQL doesn’t rely on pattern loops often because its array tools handle most use cases with less friction. Still, regular expressions help when the separator isn’t a single byte or when text includes multi character markers. Pattern extraction then blends nicely with regexp_split_to_table, which is part of its core text toolkit.

The call turns every split point into a new row. That takes care of streams that rely on markers longer than a single character.

UNNEST and Lateral Features

Workflows that depend on arrays or list shaped values rely on tools that expand those lists into rows. Engines like PostgreSQL and BigQuery treat arrays as first class data types, which means text can be split into an array and then expanded without extra loops. SQL Server takes a different path with apply, yet the result lines up with the same idea. These features help you pull values out of a packed field while keeping the logic inside the database.

Expanding Arrays With UNNEST

PostgreSQL and BigQuery rely on unnest to take an array and turn it into a set of rows. Text that holds values separated by commas is split into an array first, then passed to unnest so the engine can produce one row for each slot. Workflows built around tags, categories, or list shaped content tend to rely on this pattern because it stays short and predictable.

PostgreSQL handles the flow with two steps. The text is turned into an array through string_to_array, then expanded.

Each item lands in its own row. Queries that need to join those values against lookup tables or group them benefit from this shape. That extra structure also makes downstream filtering feel more predictable when teams work with tags or text pulled from user input.

BigQuery stays close to that structure. It supports native arrays through the split function, and unnest expands them in a single pass.

Rows come back with the text exactly as split, and the engine handles the expansion without extra clauses. Some workflows rely on this when reading log records that collect states or regions in a single field.

BigQuery also supports arrays as stored columns, so a real table can hold array typed fields. That form stays useful when the values are already structured.

Each resident expands into multiple rows, and the array field drives the expansion without extra parsing.

Lateral Expansion

Some engines rely on lateral features to expand generated tables that depend on the row being processed. PostgreSQL uses cross join lateral to feed the left side values into a function call on the right side. SQL Server does this through apply without the lateral keyword. Both styles let you expand text that belongs to a column in a real table rather than a literal string.

PostgreSQL handles a list of tags with a short expression. The lateral join gives the split function access to each row’s column.

Every post can carry any number of tags, and the join produces a row per tag. Many setups that store tags or category lists this way rely on lateral expansion to avoid looping in client code.

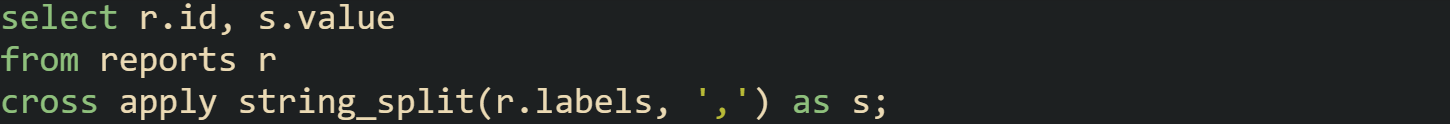

SQL Server delivers a similar structure with cross apply. The function on the right can read values from the row on the left.

Labels found in a report turn into rows that can be filtered or joined downstream. Text fields that hold comma separated attributes or codes follow this shape on a regular basis.

MySQL doesn’t support lateral joins directly, yet json_table fills the gap for many cases. A string with separators can be turned into a JSON list and expanded through a table constructor. The expression can reference columns from the current row, which lands close to the behavior of a lateral join.

Every order expands into rows for each code held in the text column. Queries that break down orders by repeated codes work well with this technique.

Conclusion

Split functions, array tools, and lateral features all push packed text into a form that suits row based work. Values that sit in a single column spread into rows, and that change gives queries room to join, filter, and group without extra effort. Engines vary in how they reach that point, yet the core motion stays consistent across them, with strings turning into lists and lists turning into rows that move smoothly through the rest of the pipeline.

![select jt.val from json_table( concat('["', replace('a,b,c', ',', '","'), '"]'), '$[*]' columns (val varchar(30) path '$') ) as jt; select jt.val from json_table( concat('["', replace('a,b,c', ',', '","'), '"]'), '$[*]' columns (val varchar(30) path '$') ) as jt;](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Bh42!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f585200-d2f1-4cca-8c54-f5ad2584b838_1496x212.png)

![select regexp_substr('north,south,west,east', '[^,]+', 1, level) as part from dual connect by regexp_substr('north,south,west,east', '[^,]+', 1, level) is not null; select regexp_substr('north,south,west,east', '[^,]+', 1, level) as part from dual connect by regexp_substr('north,south,west,east', '[^,]+', 1, level) is not null;](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!9xAD!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5ac113df-816b-4809-a7df-4df6b984a0c0_1572x104.png)

![with recursive t as ( select regexp_substr('p1|p2 | p3', '[^| ]+', 1, 1) as part, 1 as n union all select regexp_substr('p1|p2 | p3', '[^| ]+', 1, n + 1), n + 1 from t where regexp_substr('p1|p2 | p3', '[^| ]+', 1, n + 1) is not null ) select part from t; with recursive t as ( select regexp_substr('p1|p2 | p3', '[^| ]+', 1, 1) as part, 1 as n union all select regexp_substr('p1|p2 | p3', '[^| ]+', 1, n + 1), n + 1 from t where regexp_substr('p1|p2 | p3', '[^| ]+', 1, n + 1) is not null ) select part from t;](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Z8L5!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F076e4658-8081-40e2-b9e8-4688d94e3ef1_1480x376.png)

![select regexp_substr('cedar; maple; oak', '[^; ]+', 1, level) as part from dual connect by regexp_substr('cedar; maple; oak', '[^; ]+', 1, level) is not null; select regexp_substr('cedar; maple; oak', '[^; ]+', 1, level) as part from dual connect by regexp_substr('cedar; maple; oak', '[^; ]+', 1, level) is not null;](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!SVJw!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa1897a5b-03bd-4bf8-a978-c8e8b3024b4f_1631x127.png)

![select o.order_id, jt.part from orders o, json_table( concat('["', replace(o.codes, ',', '","'), '"]'), '$[*]' columns (part varchar(40) path '$') ) as jt; select o.order_id, jt.part from orders o, json_table( concat('["', replace(o.codes, ',', '","'), '"]'), '$[*]' columns (part varchar(40) path '$') ) as jt;](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Ju0p!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F85fb10b6-50d7-4e99-9f9e-7d6f7ee88252_1421x251.png)