Bit enumeration in Java gives a direct bridge between binary numbers and subsets of a small collection. Each integer is treated as a row of on and off switches, one per element, so a single loop over integer values can visit every possible combination of that collection. This style of subset generation turns up in brute force search over option sets, feature toggles, and small dynamic programming states, and Java integer and bit operators keep the mechanics precise as long as the mask stays within the width of the chosen type.

Binary Representation Of Subsets

Binary encoding gives a compact way to attach every subset of a small collection to a distinct integer. Take a set with a fixed order, pick an integer type with enough bits, then treat each bit as a yes or no switch for one element. That viewpoint turns questions about subsets into questions about bit strings. For a set with n elements, every binary number from 0 up to 2^n - 1 corresponds to one possible combination of those elements. Each element has two states, present or absent, so the total count of subsets comes from multiplying 2 by itself n times, which matches that integer range exactly.

Bits As Inclusion Flags

Binary strings make more sense the more you look into them. Let’s say you are working with a small ordered set that is written as [e0, e1, e2]. Index 0 is tied to e0, index 1 to e1, and index 2 to e2. Now pick a three bit binary string like 101. Reading from right to left, the rightmost bit is index 0, the middle bit is index 1, and the left bit is index 2. Bit 1 at index 0 says e0 is present. Bit 0 at index 1 says e1 is absent. Bit 1 at index 2 says e2 is present. That string represents the subset {e0, e2}. Binary string 000 selects no element, so it stands for the empty subset, while 111 selects all three elements at once.

Each integer in the range 0 to 7 has exactly one three bit binary form, so every subset built from [e0, e1, e2] lines up with one of those numbers. That same reasoning extends to larger sets. With four elements, four bit strings from 0000 up to 1111 cover all subsets. With n elements, bit strings of length n take the same role, and integers from 0 to 2^n - 1 carry those bit strings in their binary form. Bit value 1 always means the matching element is inside the subset, and bit value 0 always means it is outside.

For example, a single integer and a short loop are enough to turn a bit pattern into a list of chosen elements:

The method elementsFromMask treats each bit in mask as an inclusion flag. Shift by i, mask with 1, and treat any 1 result as a signal to pull items.get(i) into the subset. That loop assumes the least significant bit in mask is tied to index 0 of the list, the next bit to index 1, and so on, which matches the way binary strings were read earlier.

Binary flags do not need to represent abstract labels. They can stand for real objects or domain specific things that fit into a list. Small sets of feature toggles in a service configuration can be handled the same way:

Feature flags in this example follow the same rules as e0, e1, and e2. Each one has a fixed position in the list, the same position in the bit string, and the same interpretation of bit 1 and bit 0. That shared structure is what lets a single integer describe which toggles are active.

Index Mapping For Elements

Stable mapping between element positions and bit positions sits at the center of bit based subset work. Any time a mask is decoded into actual elements, code expects that bit index i refers to the same element index i that was used when the mask was created. If that agreement breaks, two different subsets can end up sharing the same integer, which defeats the purpose of the binary encoding.

Java collections give a natural place to store this mapping. An array or a List<T> already has zero based indices, so index 0 in that structure can be mapped directly to bit 0, index 1 to bit 1, and so on. That makes it easy to walk an integer from right to left in binary and match each bit with the corresponding item in the collection.

Two main layouts show up in real code. Many developers treat the least significant bit as index 0, then move upward through indices as they move left through bits. Some code bases reverse that relationship, treating the most significant bit in a set width as index 0. Both conventions work as long as the same rule holds everywhere that reads or writes masks. Most subset generation code in Java interview problems and everyday tooling leans toward the least significant bit convention, partly because shift expressions such as (mask >> i) read naturally with that choice.

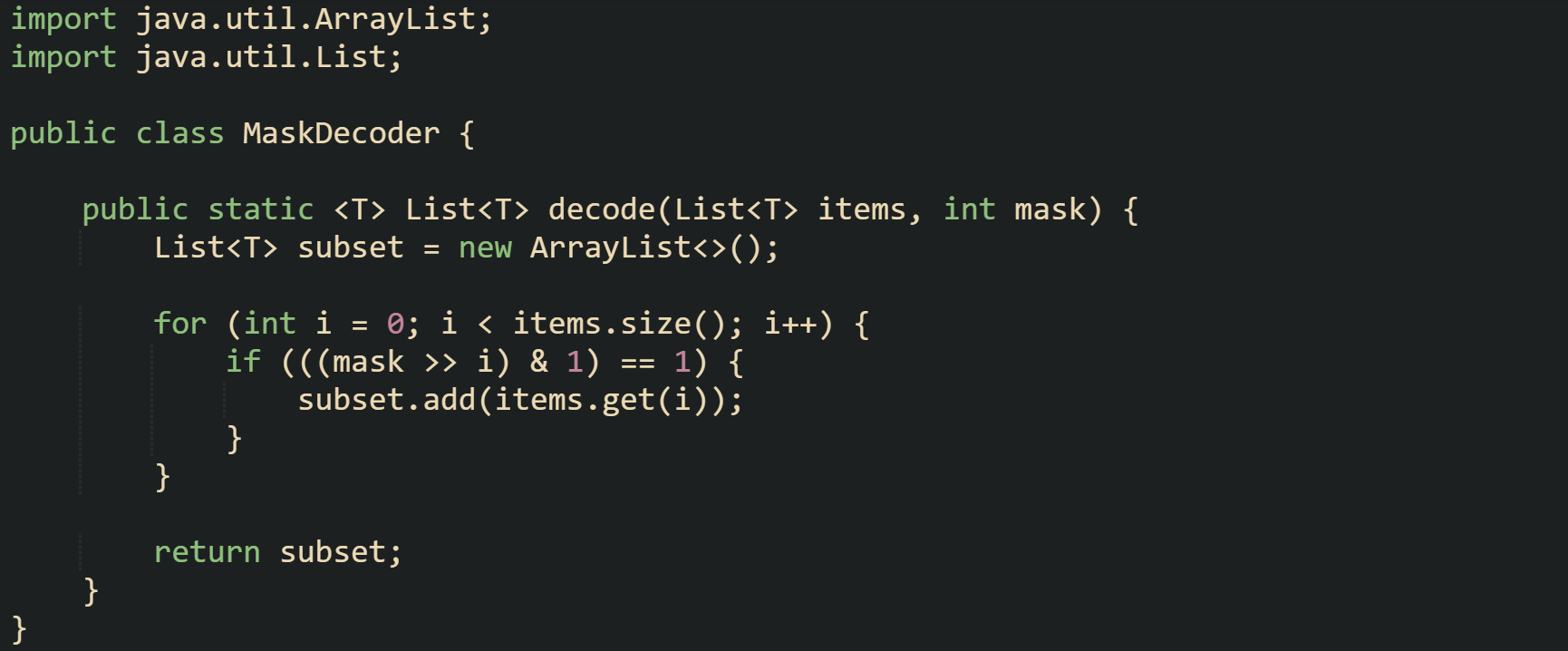

One method can take any list and any mask and return the matching subset. Other parts of the project then call that helper whenever a mask needs to be decoded, rather than duplicating the bit logic.

Any code that stores masks in a cache or a dynamic programming table can rely on this decoder to turn them back into item lists. That keeps the mapping rule consistent and also keeps bit manipulation in one well tested place.

Bit capacity of the chosen integer type sets another boundary for this mapping. An int in Java holds 32 bits. When totalMasks is computed as 1 << n, keeping n between 0 and 30 keeps totalMasks within the positive range and avoids overflow. long values hold 64 bits, so that bound moves up into the low sixties when masks are counted with 1L << n. Past that size, other representations start to make more sense, such as java.math.BigInteger or completely different subset encodings.

Work that reuses the same masks in many places also depends heavily on stable index mapping. One typical case is a memo table in dynamic programming where an integer mask marks which elements have been picked so far. Any helper that interprets those masks during later steps must use exactly the same mapping that was chosen at the start. If index 3 originally referred to a certain city, day, or feature flag, that same idea must stay attached to bit 3 in every mask, from the first call all the way to the final result.

Bit Mask Iteration In Java

Loop based enumeration turns the bit mask idea into concrete loops that Java can run. Instead of thinking only in terms of abstract subsets, code walks through every mask value in a fixed range and lets each mask drive inclusion decisions for the elements in a collection. Outer and inner loops work together here, with integer arithmetic handling the counting and bitwise operators handling the decisions about which elements belong in each subset.

Loop Structure For All Subsets

Outer loop mechanics rest on one fact from binary arithmetic. For a collection with n elements, there are 2^n possible masks, from 0 up to 2^n - 1. Mask 0 leads to the empty subset, masks closer to 2^n - 1 lead to subsets with more elements turned on. In Java, that count is usually stored as int totalMasks = 1 << n;, which uses a left shift to compute 2^n. The outer loop then walks mask from 0 up to totalMasks - 1.

Inner loop mechanics depend on the size of the input list. For n elements, bit positions 0 through n - 1 are checked in sequence. For each bit position i, the code looks at (mask >> i) & 1. If that expression yields 1, the element at index i belongs to the current subset. If it yields 0, that element is skipped for this subset. That pair of loops visits all subsets and never repeats the same subset, because each mask in the outer loop has a unique bit configuration.

Take this short example with strings that makes the control flow much easier to see:

This code ties every value of mask to a subset of the original list. Mask 0 prints an empty list. Mask 1 prints [Alex]. Mask 2 prints [Kaitlyn], and so on, up to mask 7 for [Alex, Kaitlyn, Pippin]. That sequence matches the binary forms of integers from 000 to 111 in three bits.

Some applications prefer to work with numbers rather than strings. In that setting, code looks very similar, and the main difference is the element type.

That method runs the same loop structure but uses sum to track a numeric property of each subset. While the outer loop walks through masks, the inner loop both builds the subset and updates the running total. Many problems that rely on subset enumeration follow this pattern, with different per subset calculations plugged into the inner loop.

Range and type checks matter as n grows. Control flow does not change when int masks are replaced by long masks, only the type and literal suffix, such as 1L << n.

Extracting Elements From Bit Patterns

Reading a mask back into a subset is where the link between binary values and collection indices turns into actual data. Inner loop checks interpret each bit position as a decision to include or skip one element. That logic can sit inline in the double loop, or it can live in a helper such as MaskDecoder.decode that makes the mapping easier to reuse.

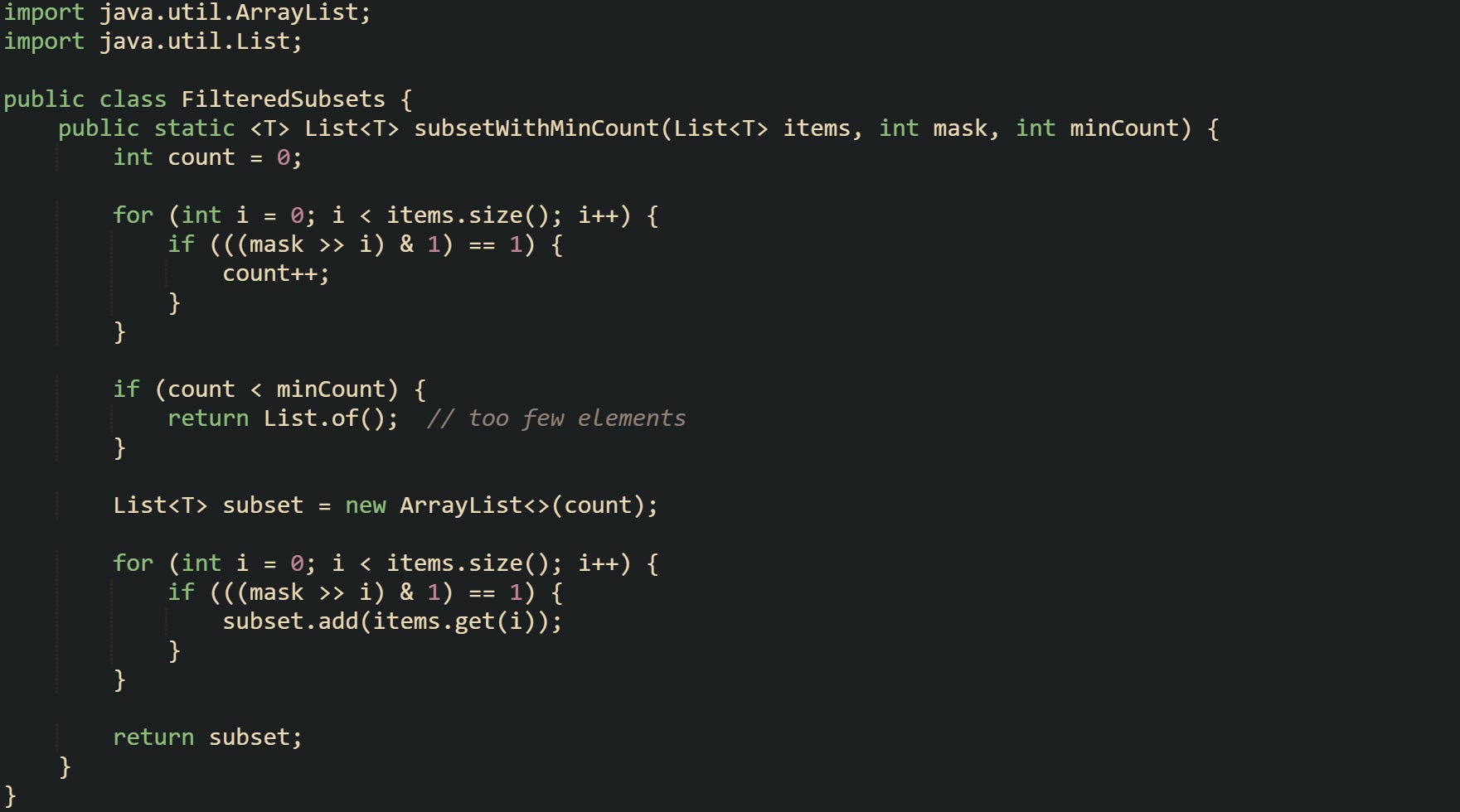

Extraction can also blend inclusion checks with additional filtering rules. Let’s say we are dealing with a collection that holds potential actions, and only subsets with at least two actions should be processed. Such a helper can scan the mask while counting bits and only build the subset when that count reaches a threshold like this helper:

Code that calls this helper can skip masks that do not meet the minimum size requirement, without having to build a full subset list for them. Both passes rely on shifting and masking, yet they separate counting from collection building, which helps keep each loop purpose easy to read.

Bitwise extraction remains the same regardless of what type T represents. Strings, integers, domain objects, or configuration records can all sit in that list, as long as the index mapping stays stable and the mask type has enough bits for the number of elements stored.

Complexity Limits In Practice

Enumeration through bit masks grows quickly in cost as n increases. Each new element doubles the number of masks to visit, because that element can be either present or absent on top of all previous combinations. Time complexity for the double loop lands at O(n * 2^n), because there are 2^n masks and up to n bit checks per mask. Memory use follows a similar curve when subsets are stored rather than processed on the fly.

Small sets sit in a comfortable region. With n = 10, there are 1024 masks, which modern machines handle easily, even when a modest per subset calculation runs inside the inner loop. For n = 15, there are 32768 subsets, which still fits many scenarios such as small search spaces or feature combinations in test utilities. At n = 20, the count rises to 1,048,576, and run time begins to stretch out, especially if code builds lists for all subsets and keeps them in memory.

Growth past that range quickly becomes a concern. With n = 25, the subset count exceeds 33 million. Fully iterating those masks in Java can take noticeable time, and storing all resulting subsets in memory becomes heavy. At n = 30, the count climbs past one billion, which pushes full enumeration outside what most everyday backend services or command line utilities can handle within practical limits.

Java itself does not place a special restriction on this technique. Shift operators and bitwise operators on int and long have stable definitions across modern Java versions. Limits come from arithmetic ranges of the primitive types and from the exponential growth in the number of masks as n grows. Ground rules that keep n small, such as restricting a feature set to a few dozen items or trimming a candidate set before enumeration, are what keep bit mask iteration suitable for real workloads.

Conclusion

Bit based subset generation in Java ties binary representation directly to how code walks through combinations. Each bit in a mask stands for an on or off choice for one indexed element, and a double loop over mask values and bit positions turns that idea into actual lists or aggregate values. With that mapping in place, developers can build helpers that decode masks, apply extra rules, and still rely on the same stable index convention. Exponential growth of 2^n subsets sets the practical limits, yet for small n this method gives an exact, mechanical way to study every combination a problem allows.

![import java.util.ArrayList; import java.util.List; public class BitMaskView { public static void main(String[] args) { List<String> base = List.of("e0", "e1", "e2"); int mask = 0b101; // binary 101 represents {e0, e2} List<String> picked = elementsFromMask(base, mask); System.out.println(picked); // prints [e0, e2] } public static List<String> elementsFromMask(List<String> items, int mask) { List<String> subset = new ArrayList<>(); for (int i = 0; i < items.size(); i++) { int bit = (mask >> i) & 1; if (bit == 1) { subset.add(items.get(i)); } } return subset; } } import java.util.ArrayList; import java.util.List; public class BitMaskView { public static void main(String[] args) { List<String> base = List.of("e0", "e1", "e2"); int mask = 0b101; // binary 101 represents {e0, e2} List<String> picked = elementsFromMask(base, mask); System.out.println(picked); // prints [e0, e2] } public static List<String> elementsFromMask(List<String> items, int mask) { List<String> subset = new ArrayList<>(); for (int i = 0; i < items.size(); i++) { int bit = (mask >> i) & 1; if (bit == 1) { subset.add(items.get(i)); } } return subset; } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!2JmD!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2d14bfdb-ec12-4257-9d6c-b41e055d54a3_1795x910.png)

![import java.util.ArrayList; import java.util.List; public class FeatureMask { public static void main(String[] args) { List<String> features = List.of( "enableCaching", "enableMetrics", "enableDebugLogging" ); int mask = 0b110; // caching off, metrics and debug logging on List<String> active = activeFeatures(features, mask); System.out.println(active); // prints [enableMetrics, enableDebugLogging] } public static List<String> activeFeatures(List<String> names, int mask) { List<String> active = new ArrayList<>(); for (int i = 0; i < names.size(); i++) { if (((mask >> i) & 1) == 1) { active.add(names.get(i)); } } return active; } } import java.util.ArrayList; import java.util.List; public class FeatureMask { public static void main(String[] args) { List<String> features = List.of( "enableCaching", "enableMetrics", "enableDebugLogging" ); int mask = 0b110; // caching off, metrics and debug logging on List<String> active = activeFeatures(features, mask); System.out.println(active); // prints [enableMetrics, enableDebugLogging] } public static List<String> activeFeatures(List<String> names, int mask) { List<String> active = new ArrayList<>(); for (int i = 0; i < names.size(); i++) { if (((mask >> i) & 1) == 1) { active.add(names.get(i)); } } return active; } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ald5!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3b47ec2b-7e79-4010-ad05-1e9c78ad660d_1788x841.png)

![import java.util.ArrayList; import java.util.List; public class AllSubsetsPrinter { public static void main(String[] args) { List<String> items = List.of("Alex", "Kaitlyn", "Pippin"); printAllSubsets(items); } public static void printAllSubsets(List<String> items) { int n = items.size(); int totalMasks = 1 << n; for (int mask = 0; mask < totalMasks; mask++) { List<String> subset = new ArrayList<>(); for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) { int bit = (mask >> i) & 1; if (bit == 1) { subset.add(items.get(i)); } } System.out.println("mask=" + mask + " subset=" + subset); } } } import java.util.ArrayList; import java.util.List; public class AllSubsetsPrinter { public static void main(String[] args) { List<String> items = List.of("Alex", "Kaitlyn", "Pippin"); printAllSubsets(items); } public static void printAllSubsets(List<String> items) { int n = items.size(); int totalMasks = 1 << n; for (int mask = 0; mask < totalMasks; mask++) { List<String> subset = new ArrayList<>(); for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) { int bit = (mask >> i) & 1; if (bit == 1) { subset.add(items.get(i)); } } System.out.println("mask=" + mask + " subset=" + subset); } } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!n9gX!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcbeab10a-3e0a-4d26-8e5d-72d1779b9d28_1756x979.png)

![import java.util.ArrayList; import java.util.List; public class SumOfSubsets { public static void main(String[] args) { List<Integer> values = List.of(5, 8, 12); printSubsetsWithSum(values); } public static void printSubsetsWithSum(List<Integer> values) { int n = values.size(); int totalMasks = 1 << n; for (int mask = 0; mask < totalMasks; mask++) { int sum = 0; List<Integer> subset = new ArrayList<>(); for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) { if (((mask >> i) & 1) == 1) { int v = values.get(i); subset.add(v); sum += v; } } System.out.println("subset=" + subset + " sum=" + sum); } } } import java.util.ArrayList; import java.util.List; public class SumOfSubsets { public static void main(String[] args) { List<Integer> values = List.of(5, 8, 12); printSubsetsWithSum(values); } public static void printSubsetsWithSum(List<Integer> values) { int n = values.size(); int totalMasks = 1 << n; for (int mask = 0; mask < totalMasks; mask++) { int sum = 0; List<Integer> subset = new ArrayList<>(); for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) { if (((mask >> i) & 1) == 1) { int v = values.get(i); subset.add(v); sum += v; } } System.out.println("subset=" + subset + " sum=" + sum); } } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!uiMi!,w_2400,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6fbe4d5a-121f-40dd-8b37-d91c0683d3da_1762x980.png)