Developers use temporary tables in SQL to store intermediate results without touching permanent schema, which helps break large queries into stages and keeps report logic readable. Database engines provide their own flavors of temporary storage, yet they share common ideas such as session scope, automatic cleanup, and basic CREATE and DROP syntax. That view of how temporary tables behave in current SQL engines, how to create and remove them, and how to pass partial results through them for multi step reports helps explain how they keep large queries from turning into a maze.

How Temporary Tables Behave In Databases

Temporary tables sit between short lived query results and permanent tables stored in the catalog. They use normal SQL syntax, yet the database keeps them separate from regular objects and ties them to a session or connection. That combination of familiar commands and special handling affects scope, lifetime, storage location, and performance, so it helps to walk through how the main engines treat them before building workflows on top.

Scope, Lifetime, Storage

Session scope is the first thing to keep in mind. MySQL, PostgreSQL, SQL Server, and Oracle all keep temporary data private in some way, but they do it with slightly different rules and naming schemes.

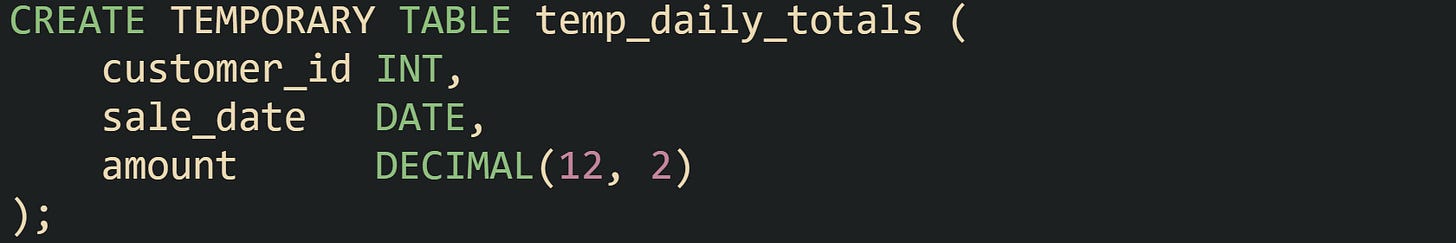

MySQL attaches a temporary table to the session that created it. No other connection can see it, and the name can be reused by other sessions with no conflict. The table vanishes automatically when the session ends, even if no DROP statement runs. The basic form looks like this:

That structure exists only for the current connection, and any attempt from another connection to query temp_daily_totals raises an error, even if the same schema and user name are involved.

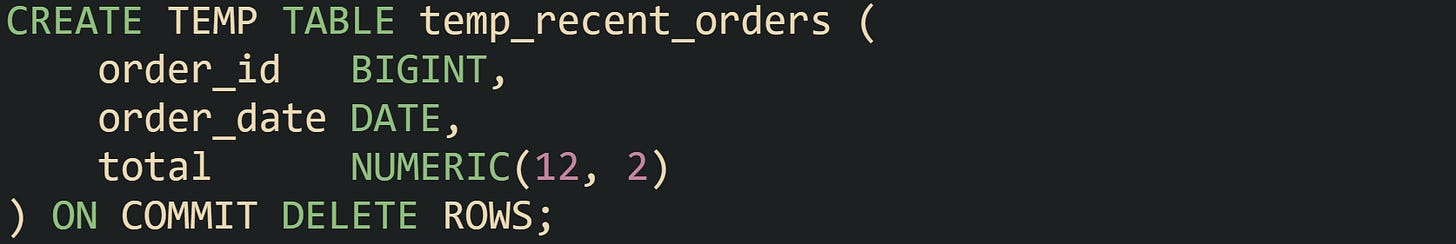

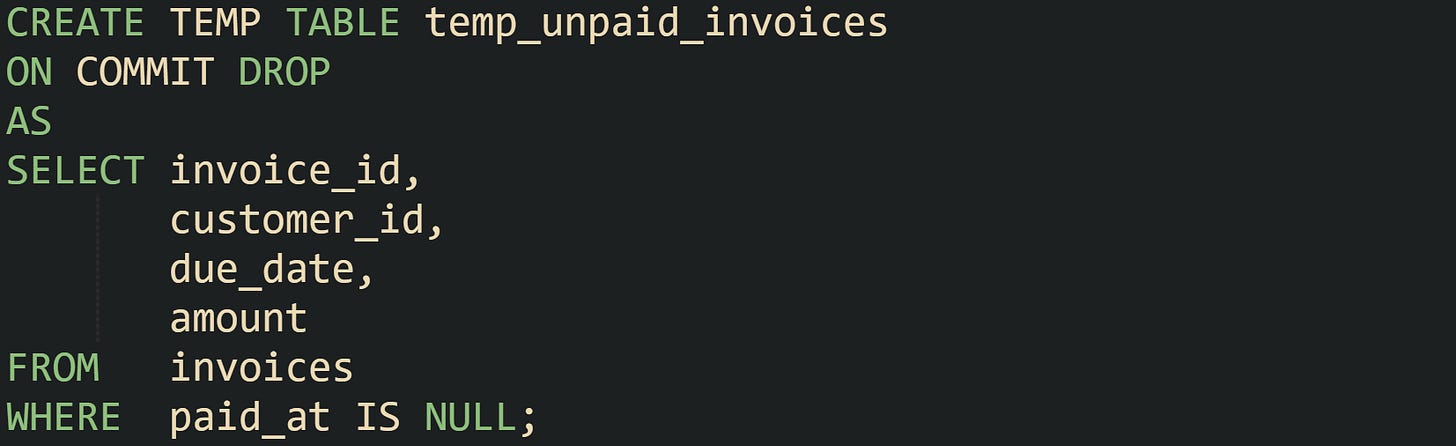

PostgreSQL also ties temporary tables to sessions, but adds more detailed control around when rows disappear. The default behavior drops temporary tables at session end. With ON COMMIT clauses, the table can be kept while rows are removed, or the table can be removed entirely at transaction boundaries. One common form looks like this:

That definition keeps the table name and columns around for the whole session, but clears all rows whenever a transaction commits. Short lived working sets benefit from this because a new transaction starts with an empty table, while code does not need to recreate the structure each time.

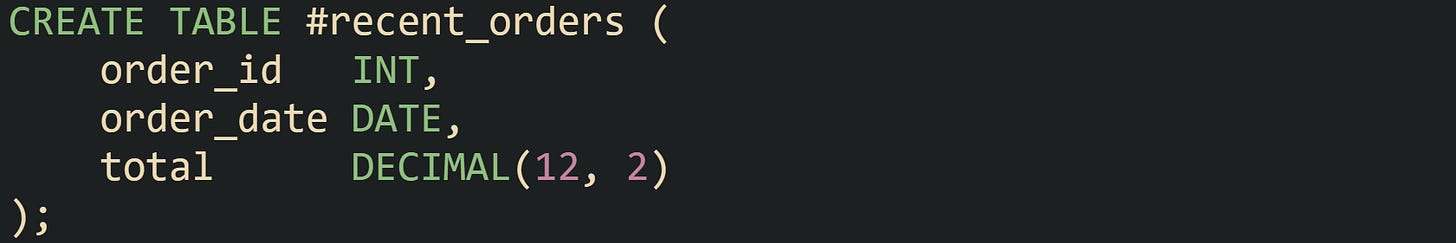

SQL Server takes a different route and uses naming rules to flag temporary tables. Names that start with a single hash mark such as #recent_orders create a local temporary table visible only inside that connection and any nested scopes spawned from it. Names that start with two hash marks such as ##scratchpad create tables that can be shared by multiple connections while at least one connection still references them. Both live in the tempdb database behind the scenes. Common usage in code looks like this:

That table disappears when the connection that created it closes, so long running application processes that reuse connections tend to drop it explicitly once they no longer need it.

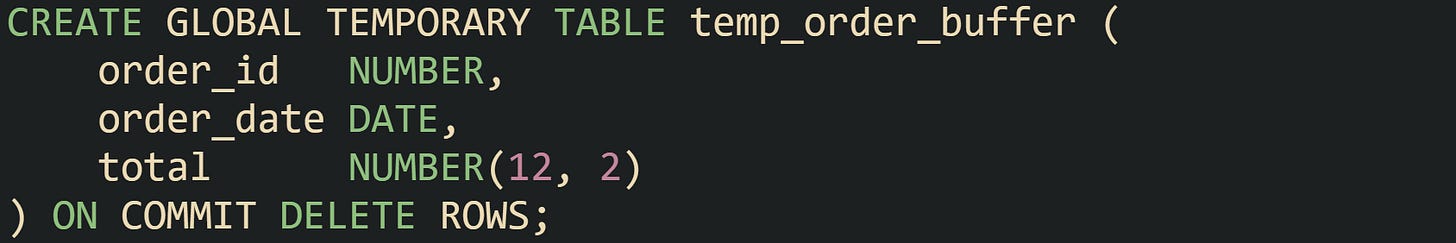

Oracle exposes global temporary tables, which work a bit differently. The table definition is permanent and stored in the data dictionary, so any session can reference the table by name. Data itself is still temporary, and each session sees only its own rows. The ON COMMIT clause controls when those rows go away. Typical usage looks like this:

Rows inserted into temp_order_buffer vanish on commit, while the table definition stays in place for reuse. Oracle stores the data in a temporary tablespace and isolates it from permanent tables in system catalogs.

Storage layout also matters. SQL Server places all temporary tables and internal work tables inside tempdb, along with temporary indexes and other supporting objects. Heavy use of temporary tables places load on that database, so administrators watch its size and I/O behavior. MySQL maintains internal temporary tables that may stay in memory or spill to disk depending on size and query features, with in memory internal temporary tables using TempTable by default (or MEMORY if configured) and on disk internal temporary tables using InnoDB. User created temporary tables use the engine given in the CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE statement, or the server default_tmp_storage_engine setting when no engine is specified. PostgreSQL keeps temporary tables in a per session schema named pg_temp and manages data in its shared buffer pool and temporary files. Oracle uses temporary tablespaces that can live on separate storage from permanent datafiles, which helps balance workloads.

Lifetime then depends both on scope rules and on the storage engine. A temporary table can vanish at commit time, session end, or connection close. Some engines drop structure and data in one step, while others keep the structure in the catalog and only purge data. Applications that create many temporary tables benefit from knowing when their databases reclaim these objects so they do not accidentally keep long lived connections full of leftover scratch tables.

Creation Syntax Across Popular Engines

Creation syntax stays close to normal CREATE TABLE commands, with small twists in each engine. The main difference is how to mark a table as temporary and how much control the command grants over commit behavior.

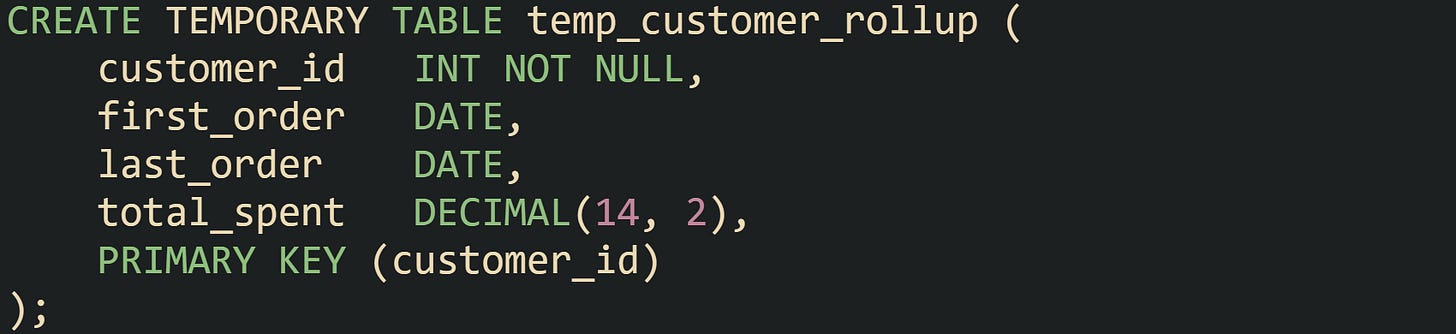

MySQL uses the TEMPORARY keyword. The table definition can be written from scratch, or a query can feed the definition through CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE AS SELECT. Both styles appear in production code, and the choice comes down to how much control is needed over column types and indexes. Direct table definitions often look like this:

And a later statement can load data into that structure through an INSERT from a query. When column types do not need adjustments, CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE can be driven directly from a SELECT:

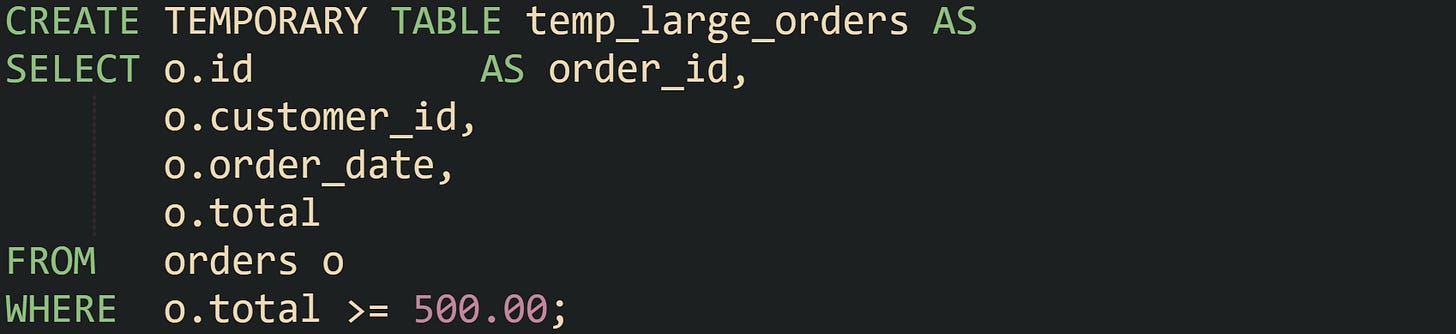

PostgreSQL uses TEMP or TEMPORARY keywords and supports the same two styles. It also adds the ON COMMIT options that were mentioned earlier, so structure and data lifetime are tuned in the definition. Query driven forms often look like this:

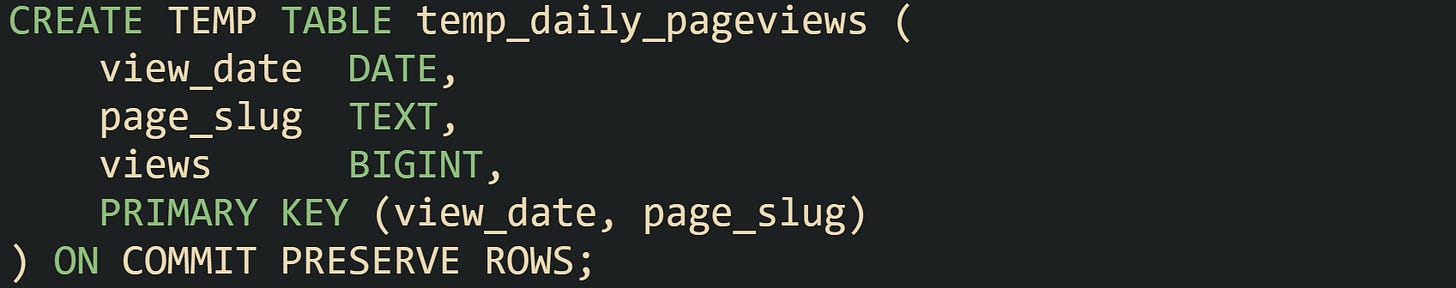

That statement creates the table, copies in the current unpaid invoices, and arranges for the table itself to disappear when the transaction commits. For longer lived scratch tables, ON COMMIT PRESERVE ROWS keeps data until session end. Indexes and constraints are allowed as well:

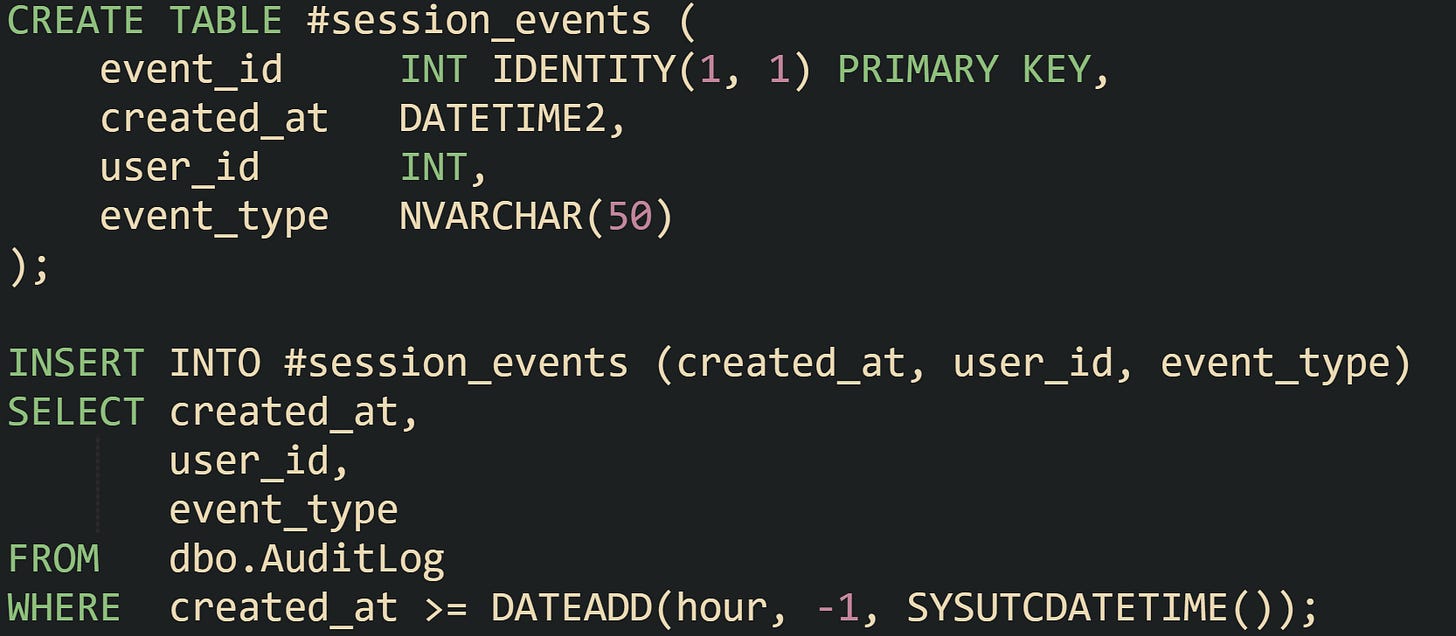

SQL Server uses regular CREATE TABLE syntax, with the table name carrying all the temporary behavior through the hash prefix. Small differences still appear, such as the database automatically placing the object in tempdb and adding an internal suffix to guarantee uniqueness. Many scripts start with a definition and follow with an insert:

The #session_events table is session scoped. Statements run through sp_executesql in the same session can read it when it was created in the outer batch. If a # table is created inside a dynamic SQL string, later outer statements usually won’t see it, so scripts normally create the table first and then fill it from dynamic SQL when needed. A similar form with ##session_events builds a global temporary table that any connection can read while it exists.

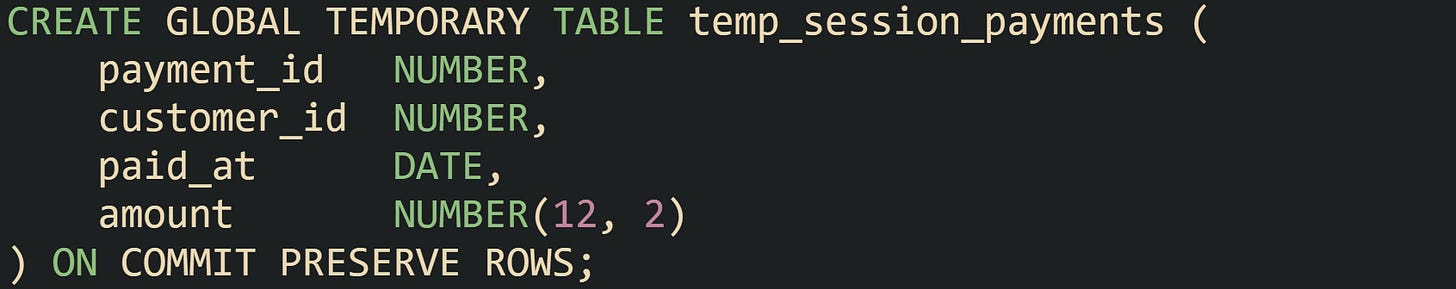

Oracle treats global temporary tables more like regular tables that just happen to store transient data. Definitions are created once and kept in the schema. Sessions reuse them in the same way they reuse permanent tables, but Oracle quietly isolates rows per session. This definition is common to see in practice:

Later sessions run INSERT and SELECT against temp_session_payments as needed, and the database handles lifecycle of the rows based on the ON COMMIT clause and session end. Data dictionaries will list this table alongside permanent tables, although the underlying storage is managed in temporary tablespaces.

Throughout these engines, the CREATE syntax for temporary tables stays close to permanent table definitions, which keeps the learning curve gentle. The main differences lie in keywords, naming conventions, and commit options, while the mechanics of column definitions, constraints, indexes, and insert statements follow familiar rules.

Practical Workflows With Temporary Tables

Temporary tables turn long, tangled queries into a series of shorter steps that are easier to reason about. Instead of cramming every join, filter, and aggregation into one statement, the work can be broken into phases that pass data through temporary tables. That same idea applies to reports, stored procedures, and ad hoc analysis in query tools, with each engine bringing its own syntax but following the same broad workflow.

Breaking Large Reports Into Stages

Large reporting queries tend to do several things within a single statement. Monthly revenue reports, for instance, may filter by date, apply currency conversion, join to customer data, and aggregate by region and product category. When all of that lives in one SELECT, small changes become hard to manage. Temporary tables provide a scratch area where each stage can store its output before the next stage picks it up.

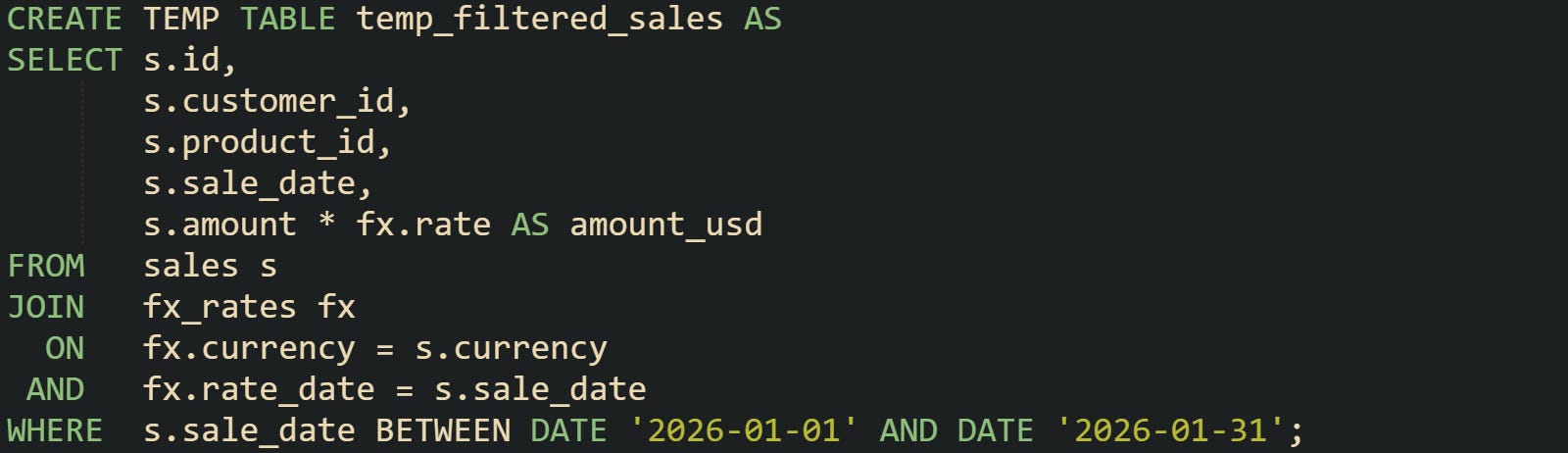

One way to handle this in PostgreSQL is to create a temporary table for the filtered and normalized base set, then another for enriched data, then run the final aggregation. The first step can filter sales and handle currency conversion:

This temporary table now holds only the rows and columns needed for the report, with values already converted to a single currency. Later steps no longer need to repeat conversion logic or scan dates outside that window.

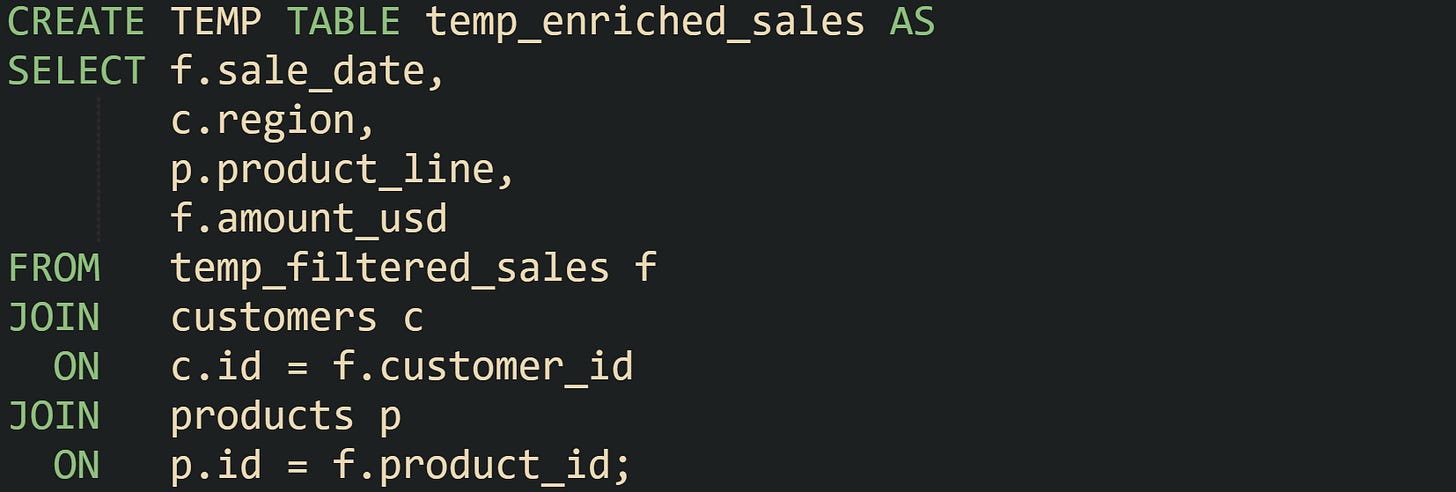

The next step can enrich those rows with dimension data, such as customer region and product line:

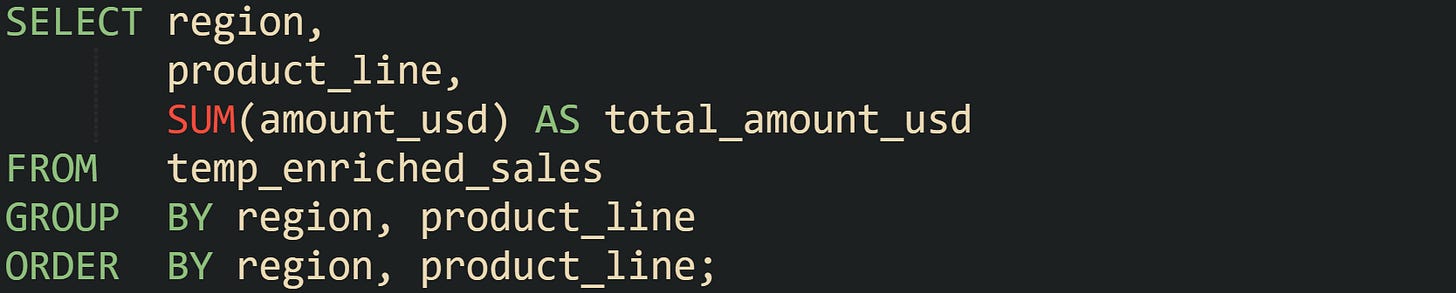

At this point, the temp_enriched_sales table contains data that is ready to aggregate in different ways. One query can group by region and product line for a high level view:

Different queries in the same session can reuse temp_enriched_sales to focus on a single region or compare a few product lines without rejoining everything. Temporary tables give the report a middle layer that can support several final queries that share the same prepared data.

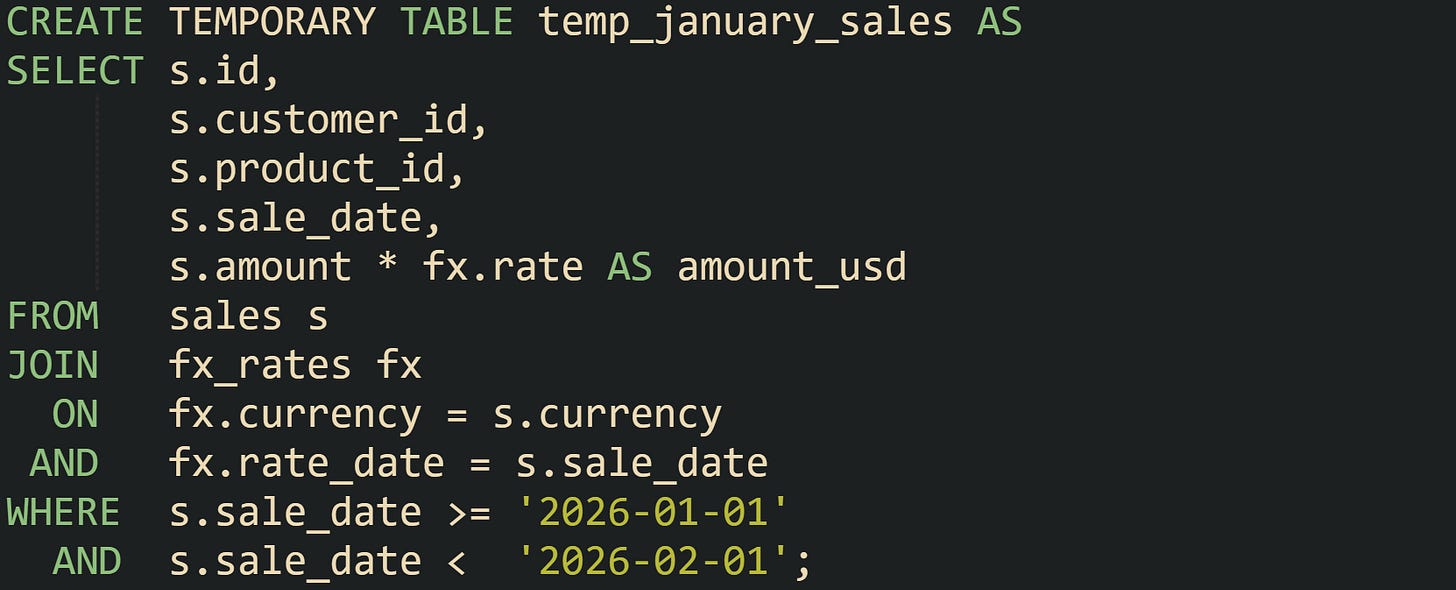

The same idea applies in MySQL with CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE and a query driven form. One filtering and conversion step can look like this:

Later statements in that session can join temp_january_sales to customer and product tables, or aggregate by different groupings, without scanning unrelated months again. Each engine handles the storage of the temporary data in its own layer, but the workflow of breaking the report into stages looks similar across platforms.

Passing Intermediate Results Between Steps

Workflows that involve several statements need a way to hand results from one statement to another without materializing permanent tables. Temporary tables are well suited for that handoff because they survive across statements in the same session and then vanish when the work is done.

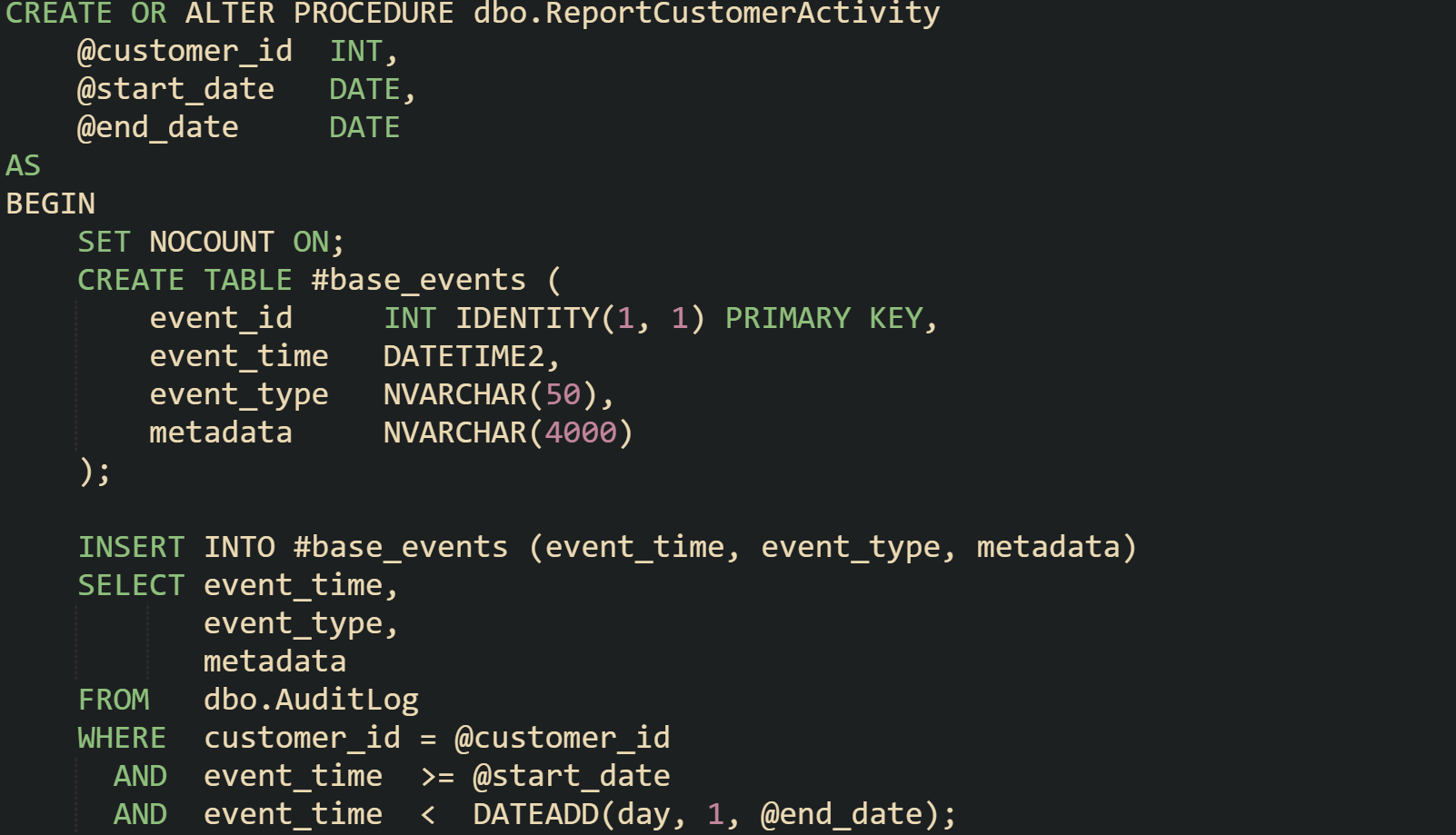

Stored procedures in SQL Server use this frequently when several queries share the same filtered base set. Suppose a reporting procedure needs to filter a large audit log down to one customer for a date range, then use that same subset to produce multiple summaries. In that case, a temporary table fits right in:

The temporary table #base_events now carries only the rows relevant to that customer and date window. Any later query inside the procedure can reference it without repeating the filters on AuditLog.

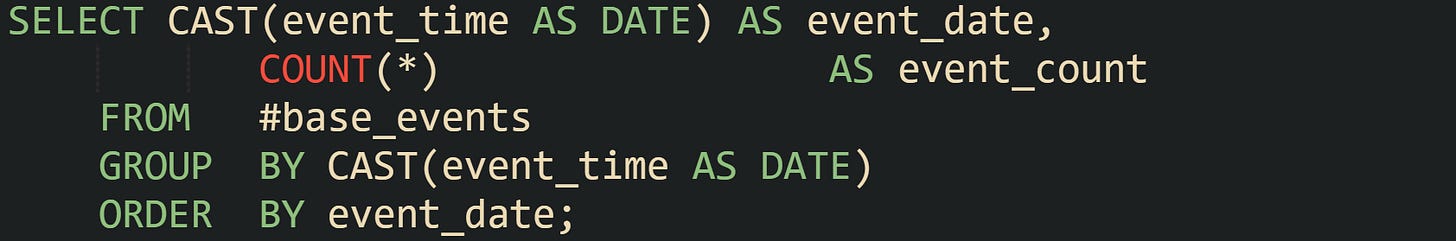

Later, a step can summarize activity by day:

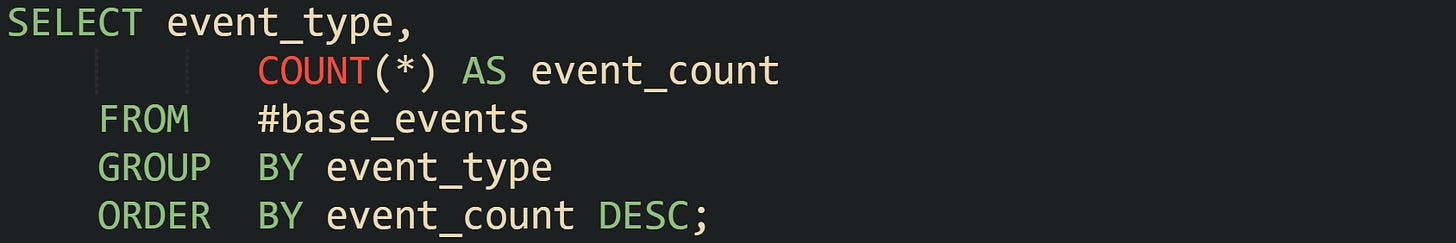

The next query in the same procedure can focus on event types:

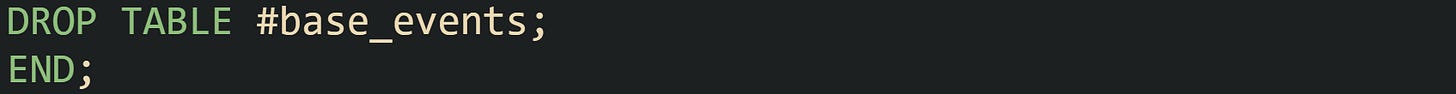

Both summaries reuse the same filtered base set, which cuts down on repeated work and keeps the procedure logic easier to read. At the end of the procedure the temporary table can be dropped to keep the connection free of leftover objects:

MySQL routines can adopt a similar practice with CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE. The session can call a procedure that creates a temporary table at the start, populates it, then runs several queries against it. That table stays private to the connection that owns the procedure call, and MySQL removes it when the session finishes, so the procedure body does not need permanent staging tables for intermediate steps.

PostgreSQL functions can also lean on temporary tables, although many workflows there prefer common table expressions or materialized views. When a function needs to write and read the same intermediate data across multiple statements, a temporary table in the same session still provides that bridge. After creation, the table sits in the pg_temp schema for that session, and later queries in the function can refer to it directly until the function drops it or the session ends.

Dropping Temporary Tables At The End

Automatic cleanup rules for temporary tables handle many cases, but explicit drops still help keep long lived sessions tidy and avoid surprises in shared environments. Connection pools in application servers are a good example. One pooled connection can serve many different requests over time, and each request may create its own temporary tables. Dropping those tables at the end of a workflow frees internal resources and reduces the risk of name clashes when another request runs later on the same connection.

Development and query tools benefit from explicit cleanup as well. When a script is run repeatedly in a tool like psql, sqlcmd, or a graphical client, leftover temporary tables from a previous run can cause errors if the script tries to create a table with the same name again. Adding DROP statements near the end of the script, or guarded drops before the CREATE statements, keeps the session in a known state and removes the need for manual cleanup between runs.

Different engines offer their own syntax for drop operations. MySQL supports DROP TEMPORARY TABLE and an IF EXISTS option so that scripts can remove tables without raising errors if those tables have already gone away. PostgreSQL uses standard DROP TABLE, also with IF EXISTS, and applies it to temporary tables in the same session in the same way as permanent ones. SQL Server supports DROP TABLE for # and ## tables and lets scripts guard the operation with DROP TABLE IF EXISTS. Oracle global temporary tables can be cleared with TRUNCATE TABLE when the structure should remain for reuse, or removed with DROP TABLE when the definition should go away as well.

Global temporary tables in SQL Server deserve special attention because they are visible across connections while any connection still references them. If DROP TABLE ##scratchpad is forgotten, shared staging data can remain in place and confuse later sessions that read from that name. Dropping global temporary tables as soon as shared work finishes prevents that bleed over and keeps the shared namespace predictable.

Temporary tables give SQL workflows a flexible middle ground between one shot result sets and permanent schema, but they share resources with other parts of the database engine. Creating them thoughtfully and dropping them when their job is done keeps those workflows efficient and avoids side effects in pooled or long running sessions.

Conclusion

Temporary tables give SQL developers controlled, short lived storage between single query results and permanent schema, with scope and lifetime governed by engine specific rules. MySQL and PostgreSQL attach temporary tables to sessions, SQL Server binds local and global temporary tables to connections through hash prefixed names in tempdb, and Oracle treats global temporary tables as permanent definitions with transient per session rows. In all of these engines, temporary tables rely on standard CREATE and DROP statements while acting as a staging layer where intermediate rows are written, queried by later statements in the same session, and then removed through automatic cleanup or explicit drop commands.