Handling time zones in relational databases affects how users read dates, how reports stay aligned, and how billing and logging stay correct across regions. Many systems store and compare timestamps without regard for daylight saving changes or locale settings, which can cause duplicated rows, gaps in query results, or confusing clocks on screen. Modern database engines represent time values with types that distinguish local and UTC timestamps, store data in stable forms, and support queries that keep results accurate when time zones and daylight saving rules change.

How Databases Store Time Values

Relational databases carry several time-related types that all look similar at first glance but behave differently once time zones and daylight saving rules enter the picture. Storage choices here affect how queries behave years later, how joins between tables line up on timestamps, and how client code interprets results. This section walks through common SQL types, how they relate to UTC and local time, and how table definitions set a stable base for time zone safe work in later queries.

Timestamp Types In Common Databases

Relational engines usually separate a calendar timestamp from any concept of region or offset. That separation shows up in the names of built-in types.

PostgreSQL has timestamp and timestamptz. The first one holds a calendar date and clock time with no offset information. The second one represents an instant on the global timeline and interprets inputs in a time zone context, then stores the instant internally in UTC. When a timestamptz value is read back, PostgreSQL converts the stored instant to the session TimeZone setting before formatting it.

MySQL uses DATETIME for a calendar value with no time zone and TIMESTAMP for values that pass through UTC on the way into and out of the table. A TIMESTAMP column takes the current session time zone into account, converts the value to UTC for storage, then applies the reverse conversion when the row is read.

SQL Server families of types have similar splits. Types such as datetime and datetime2 store a calendar timestamp without an offset, while datetimeoffset keeps both the timestamp and a numeric offset such as +02:00. That offset tells SQL Server how the original local clock related to UTC at the time of insertion.

Engines do not attach region names such as America/Chicago or Europe/Berlin to individual rows. Locality is usually stored in separate attributes on a user, tenant, or site record. The timestamp column then focuses on representing an instant or a local calendar value.

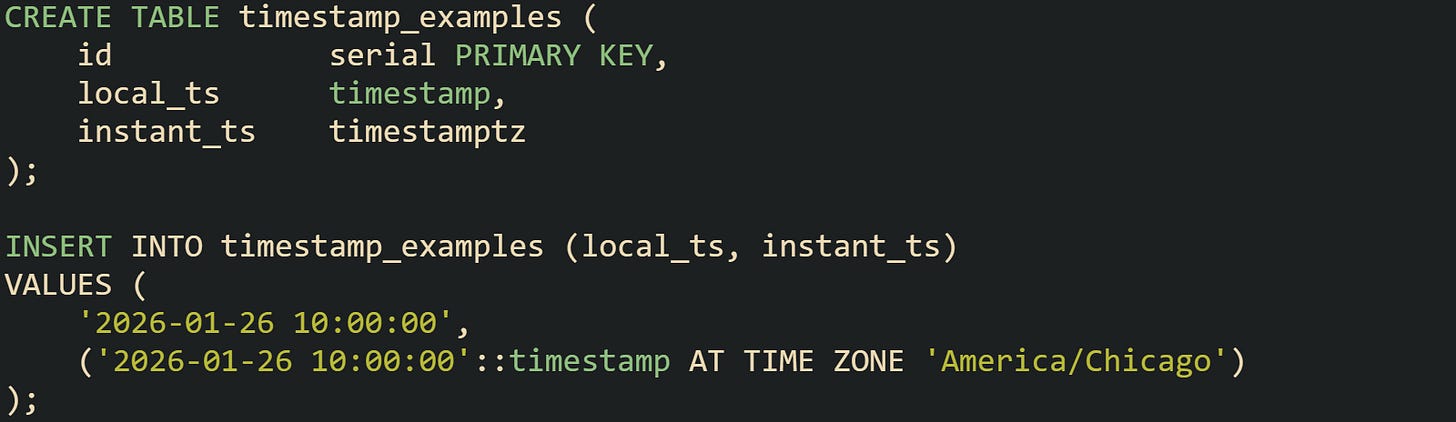

In PostgreSQL, two columns side by side make the contrast more visible:

After running this insert from a session set to UTC, a query that selects both columns will reveal that local_ts keeps the literal calendar value, while instant_ts shows the same instant adjusted for session time zone rules. That contrast hints at why a timestamptz column works better for cross-region work.

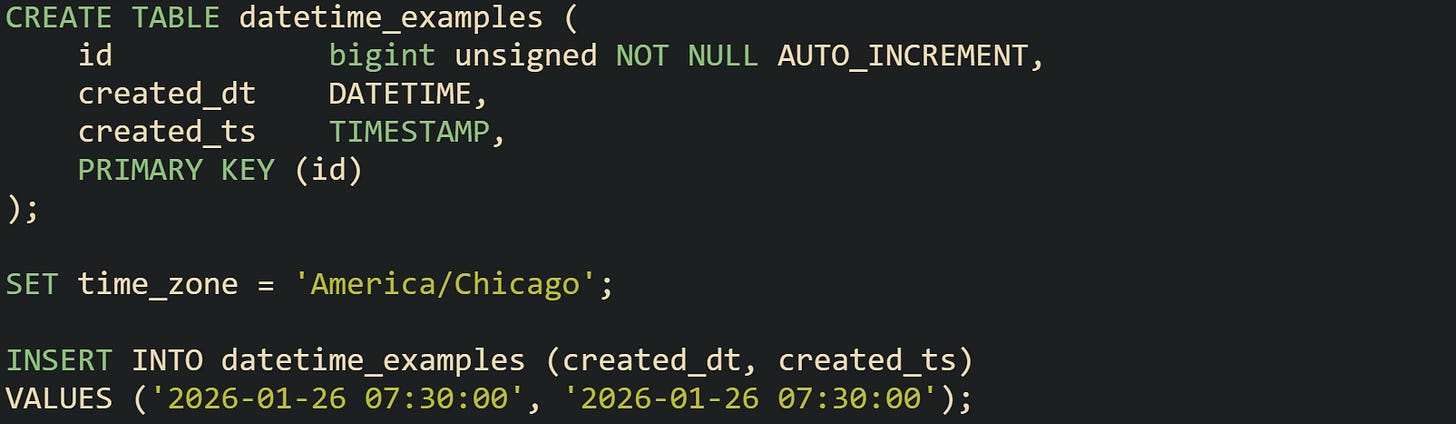

MySQL tells a similar story with DATETIME and TIMESTAMP:

Subsequent reads with time_zone = '+00:00' will show created_dt as the original local value and created_ts as the corresponding UTC time. That difference matters once rows come from multiple regions or once queries compare timestamps across large ranges.

These type pairs explain why many systems standardize on one storage convention. A column that represents an instant in UTC gives consistent comparisons regardless of where inserts originate.

Why UTC Storage Reduces Surprises

Daylight saving rules introduce clock changes that create repeated local times and gaps. During a fall transition, a local clock may step back from 02:00 to 01:00, so values between 01:00 and 02:00 occur twice with different offsets from UTC. During a spring transition, a window of local times simply does not occur.

Local-only timestamps with no offset cannot distinguish between the two instances of a repeated time. Queries that filter on local values alone may miss rows or return overlapping periods with no indication that something unusual happened on that date. UTC values avoid these problems because they never repeat and never skip intervals due to daylight saving adjustments. Each 2026-01-26T10:00:00Z style instant is unique and increases steadily over time. When timestamps are stored as UTC, range filters align with the actual timeline.

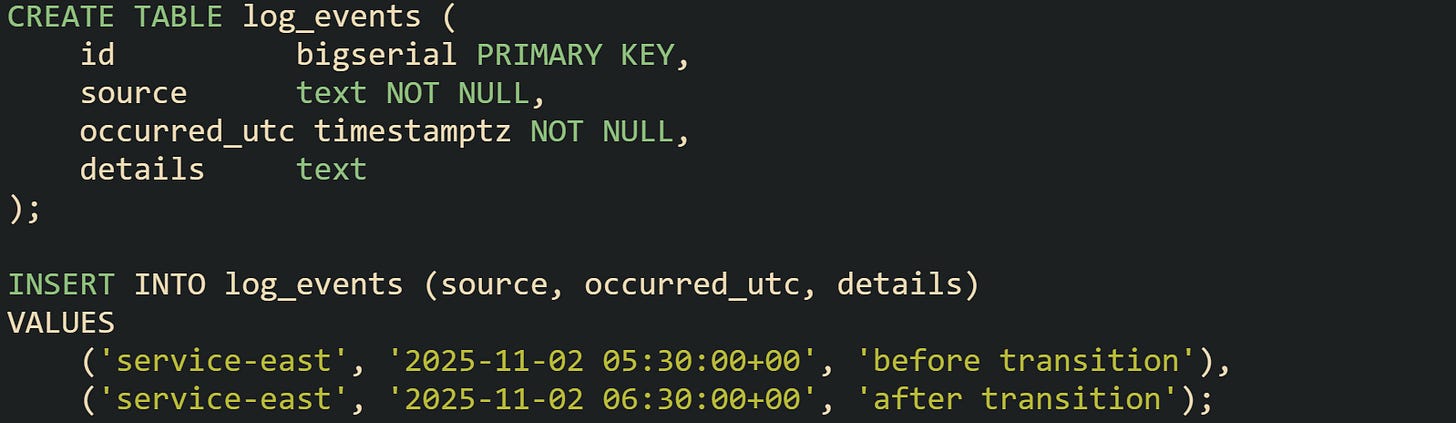

Let’s say we are working with a logging table that records events from several U.S. regions and stores them in UTC in PostgreSQL.

Those two rows may correspond to two local times that both print as 01:30 in a region that moves from UTC-04 to UTC-05 on that date. A query that filters on occurred_utc between 05:00 and 07:00 UTC covers the entire change without special handling. Any reporting query that later converts these values to local time can still show both periods clearly, because the UTC base stayed consistent.

Systems that store local timestamps without an offset often run into gaps when business rules talk about days in specific regions. If a date range is expressed in local terms, the safest pattern is to translate that range to UTC and then compare only in UTC. That conversion step relies on engines having a stable UTC representation for each stored instant. In practice, UTC storage pairs well with a separate notion of user or tenant time zone. Timestamp columns hold UTC, while a user table or configuration file carries the IANA time zone name used for display and local business rules. That split keeps arithmetic and comparisons in UTC and postpones regional concerns to a later formatting or conversion step.

Column Definitions For Time Zone Safe Data

Schema choices lay the groundwork for reliable behavior later. Columns that represent events, orders, log entries, and similar records benefit from expressing time as instants, not ambiguous local values.

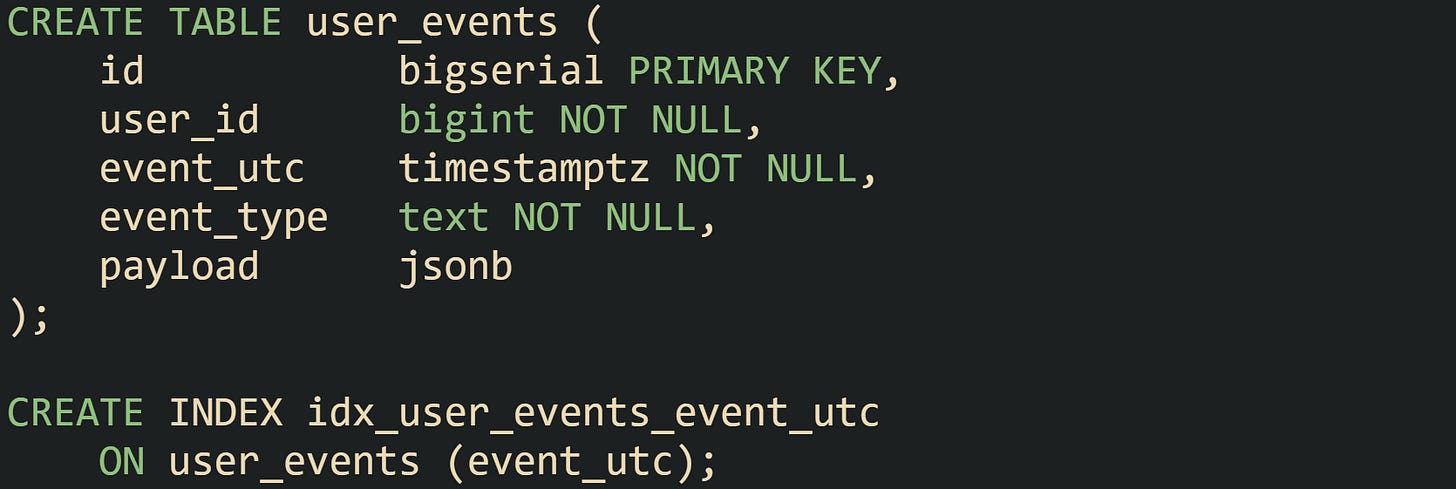

PostgreSQL encourages this pattern with timestamptz. Take this common table for tracking user events:

Values inserted into event_utc are interpreted as timestamps with time zone and then stored as UTC. When a client connected from Eau Claire, Wisconsin inserts 2026-01-26 09:15:00-06, that value represents the same instant as a client in New York inserting 2026-01-26 10:15:00-05. Both arrive in the table as a single timeline.

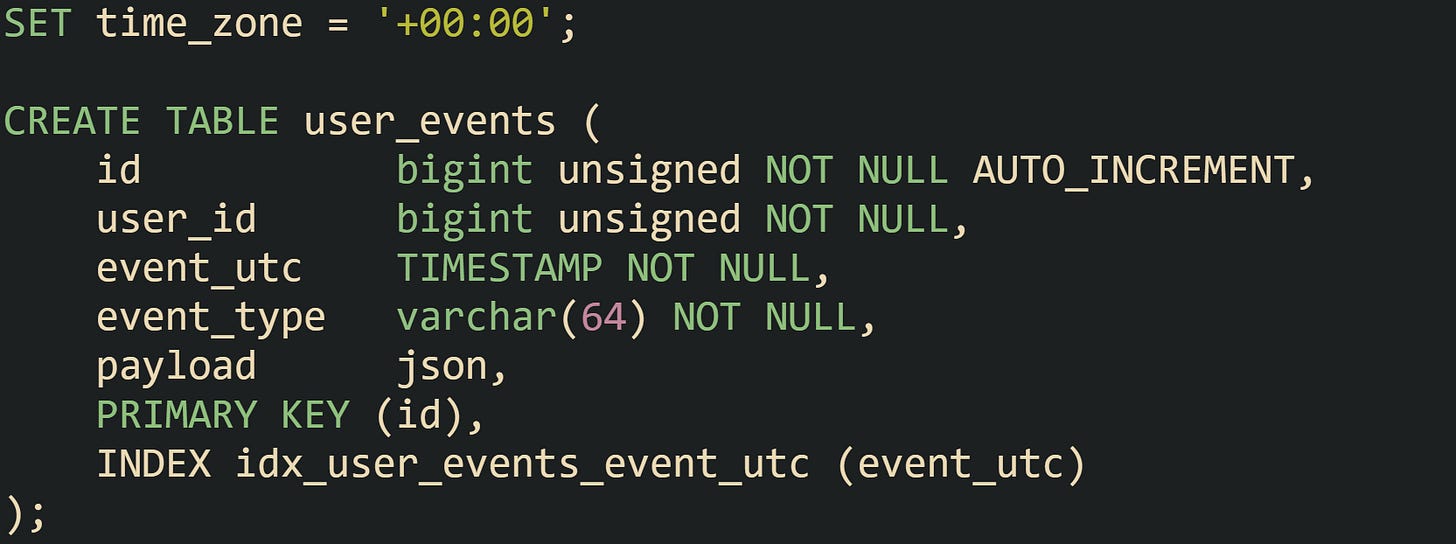

MySQL pairs a TIMESTAMP column with conventionally UTC client sessions to reach a similar layout:

Client libraries that set the connection time zone to UTC keep this column aligned with the same global clock as PostgreSQL timestamptz. Inserts from various regions become comparable instants in the table.

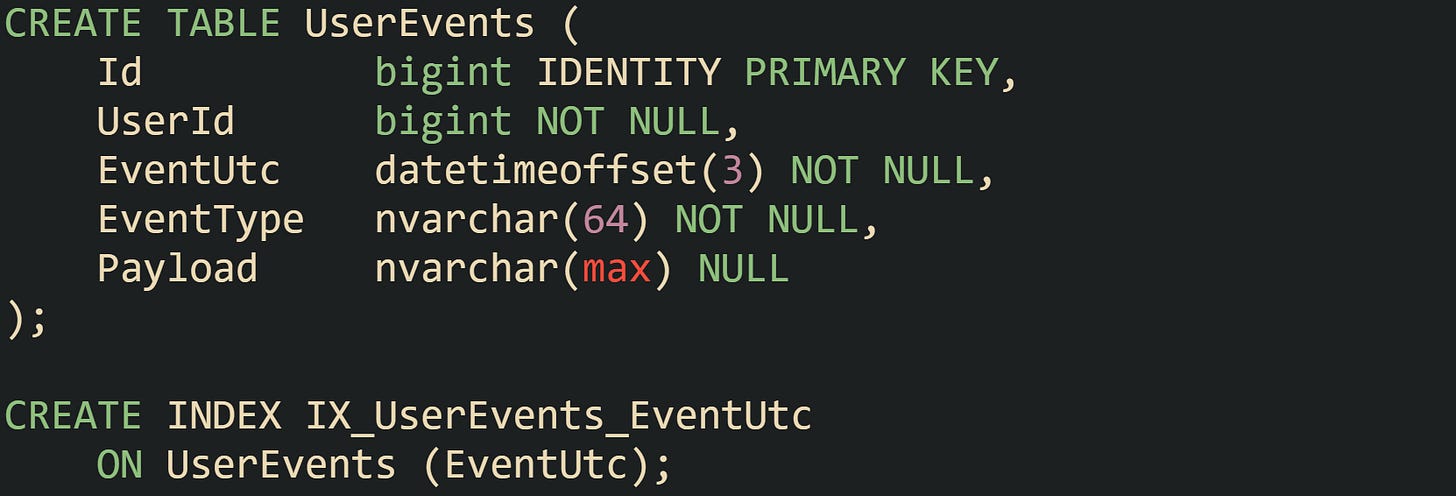

SQL Server tables that hold UTC instants typically use datetimeoffset with an offset of zero:

Application code then normalizes timestamps to UTC before inserting. An insert that sends 2026-01-26 14:05:00 +00:00 records a precise instant that can participate in cross-region joins and comparisons.

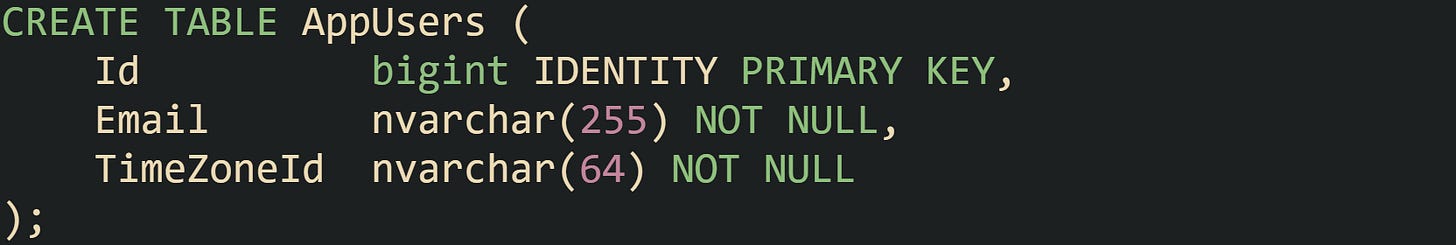

In many applications, a separate table stores user preferences, which include the time zone used for display and business rules.

Values in TimeZoneId match identifiers such as America/Chicago in engines that rely on IANA names or Central Standard Time for features that expect Windows time zone labels. Queries can join UserEvents with AppUsers when they need to convert EventUtc values to local time for Alex in Wisconsin or Kaitlyn in another region.

By separating a UTC instant from regional metadata in this way, storage stays stable across software upgrades, daylight saving rule changes, and user moves between cities. The database holds a consistent timeline, while time zone safe query layers decide how to interpret that timeline for a specific audience.

Converting Time Zones In Queries

Queries that return timestamps often need to speak in the user’s local clock, even when storage stays in UTC. Reporting screens for people in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, scheduled jobs in Europe, and audit exports for a central team all rely on the same stored instants but need different views of local time. Database functions that work with session zones, named regions, and numeric offsets give that flexibility as long as they are paired correctly with UTC columns.

Converting For Users With AT TIME ZONE

Many databases provide a clause or function that shifts an instant from one time zone frame to another while honoring daylight saving rules. PostgreSQL attaches AT TIME ZONE to timestamp expressions, SQL Server does the same with datetimeoffset, and MySQL relies on CONVERT_TZ. These tools let a query take a UTC instant that came from storage and present it as a wall-clock time for a specific region.

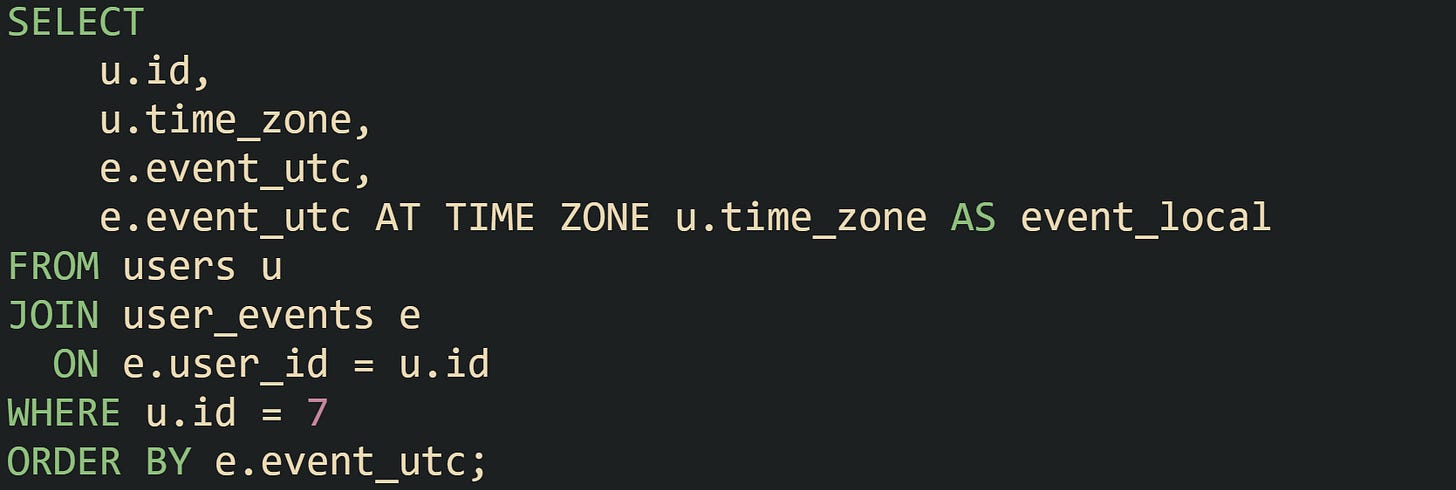

PostgreSQL treats a timestamptz column as an instant and a named zone as a regional view of that instant. A query that wants to show events for Alex in Eau Claire can cast stored values into central time for that user.

Here, the expression reads a UTC instant from event_utc and renders a local timestamp for the given zone. Output for a date in March or November automatically follows daylight saving changes for that region, with no manual offset arithmetic.

Many applications store a time zone choice per user instead of hardcoding it in the query. That preference can live in a users table and be joined at query time so each row converts to the right local clock:

This design allows Kaitlyn in one zone and Pippin in another to share the same user_events table. Each person sees times aligned with their own region, while the stored data stays on a single UTC scale.

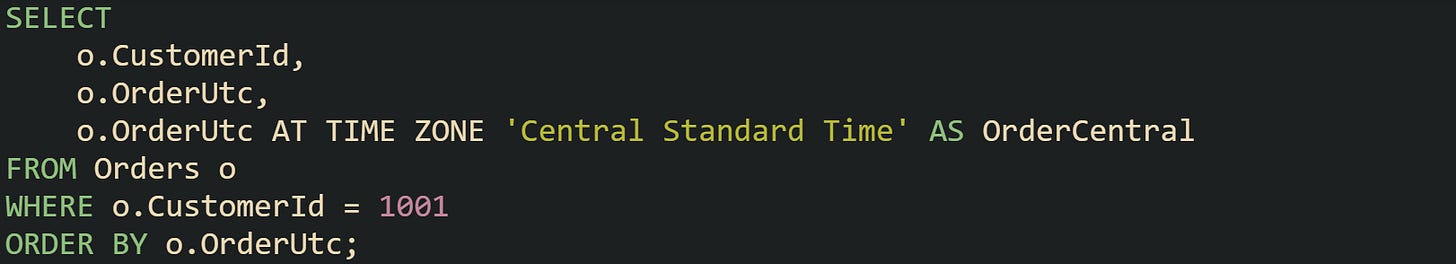

SQL Server uses a similar clause with datetimeoffset values. Order activity stored as UTC instants can be projected into central time for reporting:

Windows time zone names such as Central Standard Time and Pacific Standard Time map to collections of offset rules, including daylight saving changes across many years. When the AT TIME ZONE clause runs, SQL Server finds the right offset for each instant and uses it while formatting local values.

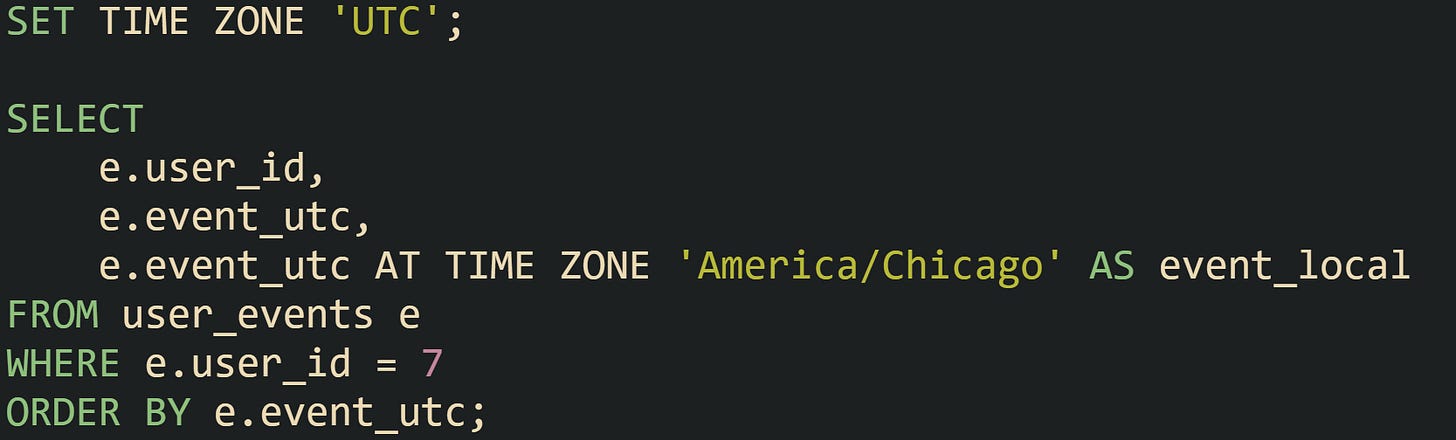

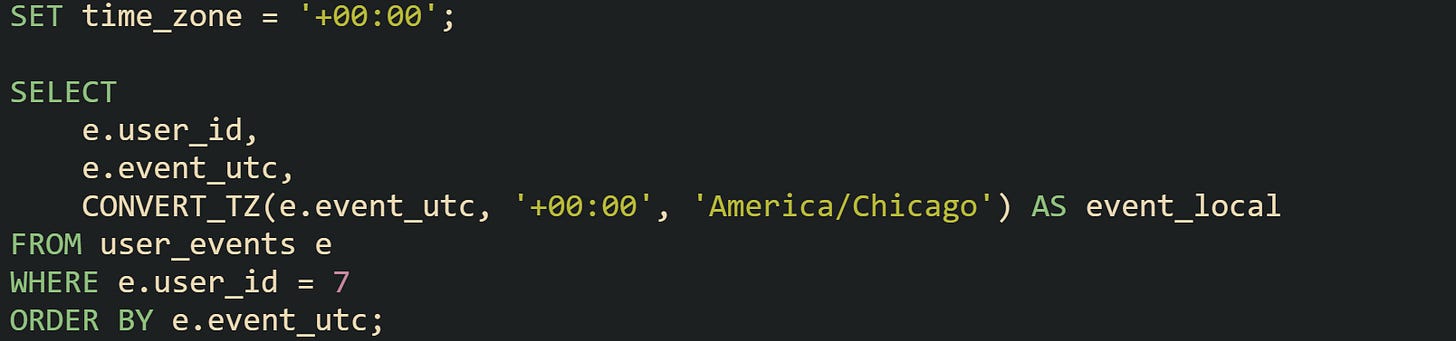

MySQL leans on CONVERT_TZ for similar work. In a schema where events are stored in a TIMESTAMP column interpreted as UTC, a query can shift them to a region like America/Chicago.

That function takes the original offset and the target zone name and produces a local DATETIME value. Time zone tables in MySQL must be loaded so that names like America/Chicago carry the right historical rules.

Systems often have a mix of public dashboards, exports, and background jobs. Queries can use AT TIME ZONE or CONVERT_TZ in slightly different ways depending on the target. Scheduled summaries of a jobs could always convert to UTC or a central business zone, while a user-facing endpoint joins to a users table and respects each person’s preference.

Filters That Stay Correct Around DST

Filtering by local dates and times adds a second layer of complexity, because the requested range usually comes from user input in a specific region. People think in terms of local days, business hours, or weekends. Storage in UTC turns those concepts into ranges of instants that sometimes have length 23 or 25 hours on days with daylight saving changes. Reliable filters treat local ranges as an intermediate concept and translate them into UTC bounds before they touch stored data. That two-step plan avoids gaps and overlaps that would otherwise appear during spring and fall transitions.

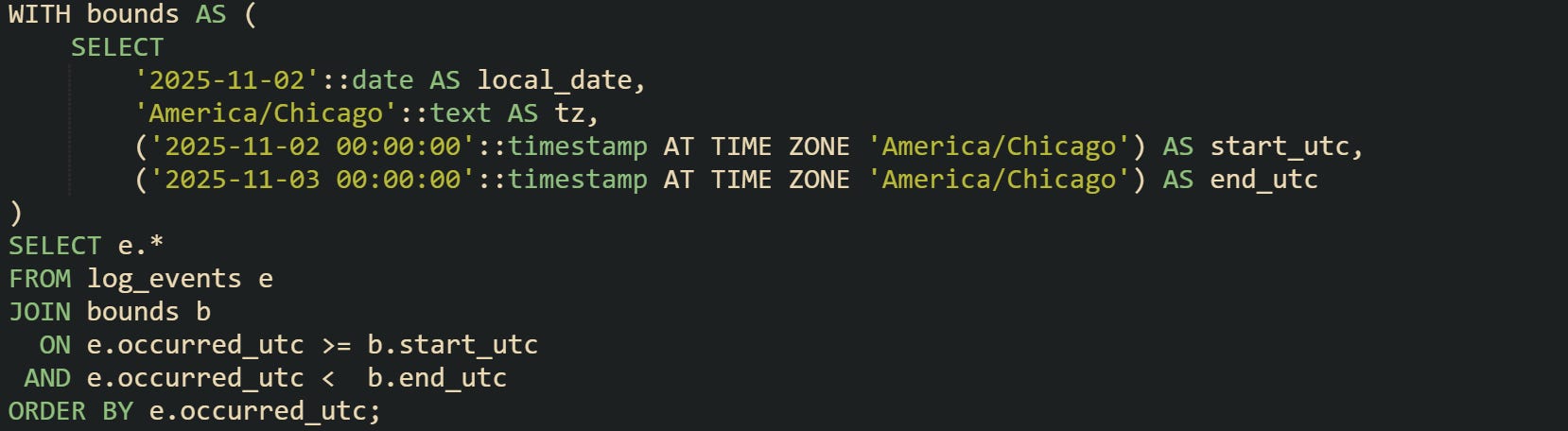

PostgreSQL offers a good set of tools for this translation. One common case is a user who wants all events for a local calendar day. The application receives a date and a time zone and builds the matching UTC range.

Local midnight bounds map to a pair of UTC values that cover one full local day. On a normal day with no clock change, that range spans 24 hours of UTC time. On a day where clocks fall back, the range spans 25 hours and covers both copies of any repeated local time. On a day where clocks jump forward, the range spans 23 hours and skips the local period that never occurs.

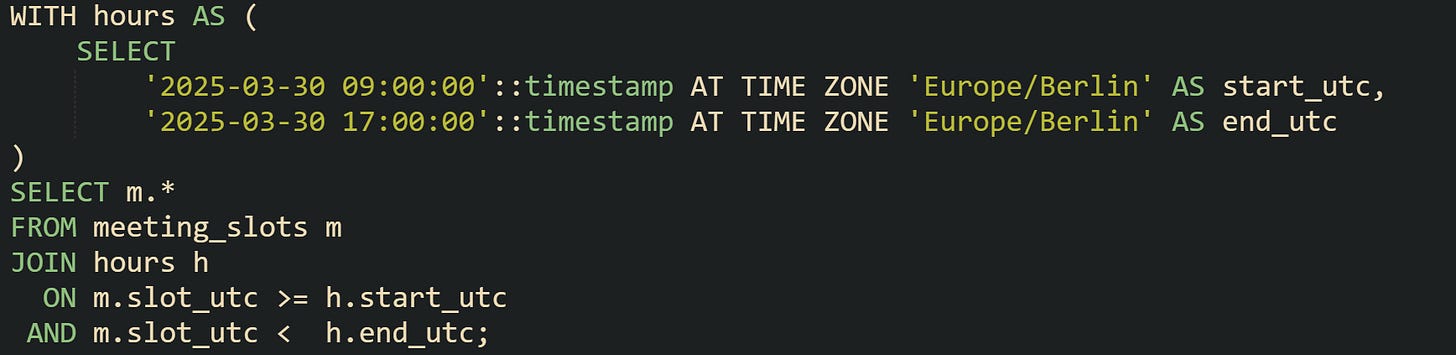

Range filters that focus on working hours use the same pattern. An office that runs from 09:00 to 17:00 local time needs those bounds converted to UTC before hitting the table:

Daylight saving changes in Berlin are handled by AT TIME ZONE. If a spring change removes one hour from the local pattern, the resulting UTC span reflects that shorter window, and meetings logged in slot_utc still filter correctly.

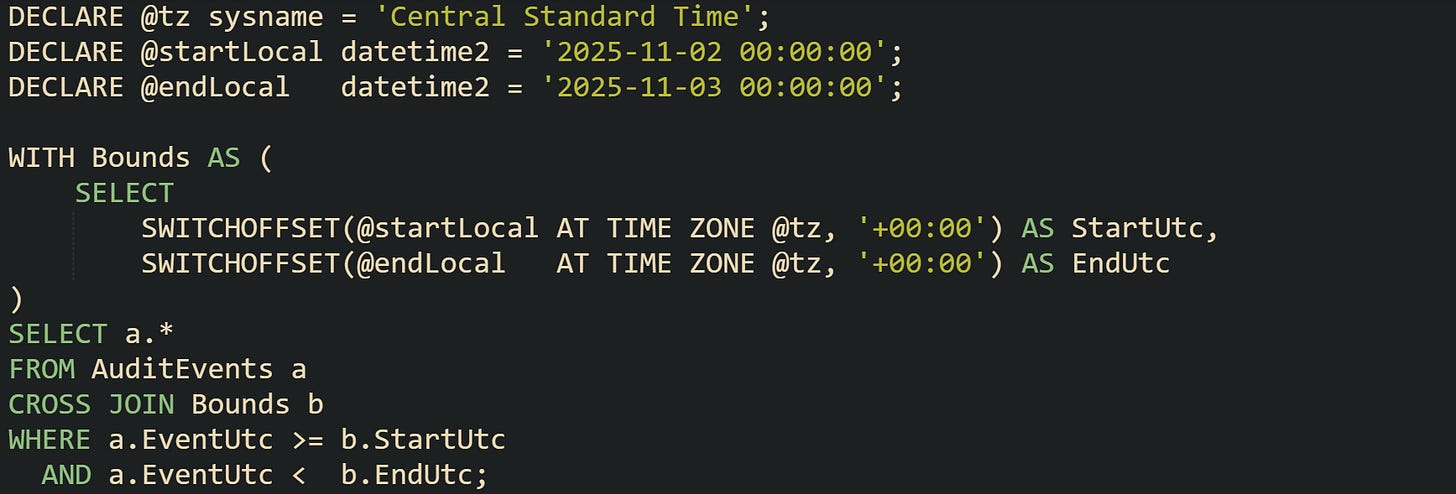

SQL Server uses datetime2 and datetimeoffset for a similar style of filter. Queries that select audit events for a local window first turn local boundaries into datetimeoffset instants for a region such as central time:

The AuditEvents table stores EventUtc as datetimeoffset with offset zero. StartUtc and EndUtc now represent precise instants, even on complex days with clock changes. The filter then works with those instants and avoids reasoning in local time until data is rendered for a report.

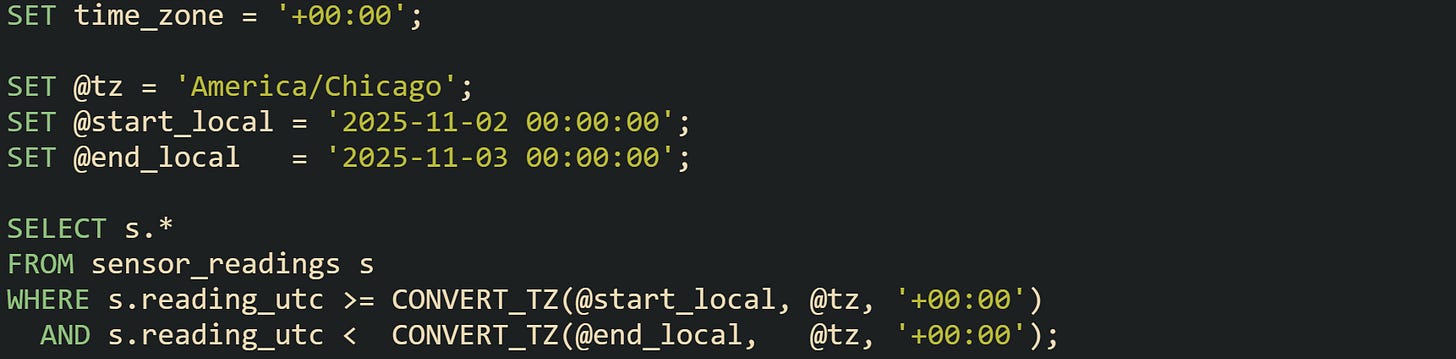

MySQL applies CONVERT_TZ in a similar two-step fashion. For a local day range, input values in local time are converted to UTC, then used in the WHERE clause:

MySQL uses whatever rules are loaded into its time zone tables for named zones in CONVERT_TZ. When laws change, admins reload those tables and restart the server so conversions stay current.

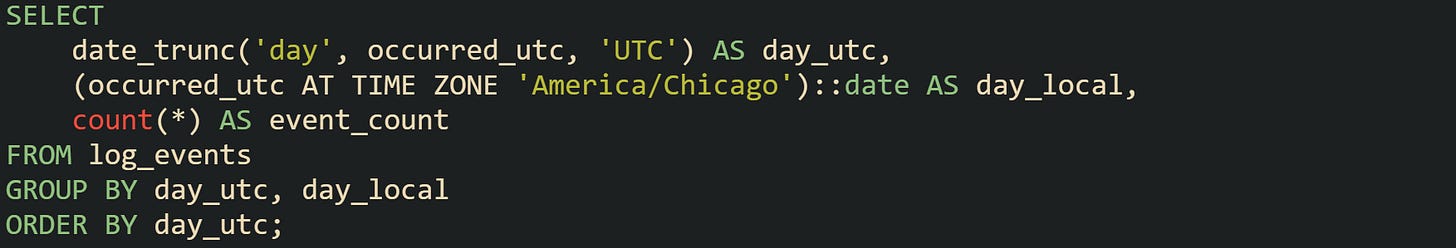

Many reports need grouping by local day or hour, not just filtering. Plenty of reports base their grouping expressions on UTC columns and then project companion local values for display. That way, an aggregation query keeps its numeric logic consistent on UTC while still exposing local buckets.

Aggregations that group on UTC while also carrying a local label stay stable when people move to new regions or when future legal changes adjust daylight saving boundaries. The raw data and group definitions still rely on UTC instants, and only the presentation layer needs to worry about how those instants appear on a given wall clock.

Conclusion

Careful handling of timestamp types and conversions keeps time data consistent across regions and daylight saving changes. Storing instants in UTC with types such as PostgreSQL timestamptz, MySQL TIMESTAMP, or SQL Server datetimeoffset gives queries a stable timeline for comparisons, joins, and indexing. Conversion functions such as AT TIME ZONE and CONVERT_TZ then project those instants into local clocks for users while filters and groups stay anchored in UTC. Translating local ranges into UTC bounds before filtering and aggregating keeps reports, billing runs, and audits aligned with real-world calendar rules even as time zone databases evolve.