Data sets tend to grow in ways that leave stray duplicates behind from imports, batch processes, or plain accidents. Extra copies of a row can distort reports, slow joins, and waste storage that could be used for better things. Good duplicate removal doesn’t have to feel risky, because keeping one solid record while trimming the rest follows a repeatable pattern once you see how modern SQL engines read row identity, sort values, and filter result sets. The main idea is to clear the excess while staying in full control over which entry survives. Two stable techniques handle nearly every case. ROW_NUMBER() gives a ranked view of matching rows so one record can stay while the rest are removed, and GROUP BY reshapes matching clusters so the table returns with a single row for each set. Both techniques stay standard practice in PostgreSQL, SQL Server, MySQL 8, and MariaDB 10.2 or newer, where window functions work as expected.

Modern Dedup Mechanics

Data cleanup always starts with how a database interprets matching rows. Databases won’t treat two records as duplicates until you point out which columns form the match. That foundation drives every later step. When those match columns are set, the engine can group identical rows into small clusters that carry the same values across those fields. SQL engines grew stronger at handling this once window functions became part of everyday work, because they make it possible to scan a table, form clusters, number rows inside those clusters, and keep everything in view without extra passes or temporary client logic.

Row Identity in Practice

Clustering starts with columns that define a match. Those columns vary by table, but they usually include fields such as email, phone numbers, product codes, or customer identifiers. Once those columns are named, the database groups matching rows into the same bucket. Groups can be tiny or large depending on how data entered the system. Some tables get hit by repeated imports where the same record landed three or four times through an automated job. Others collect extra rows through a service that didn’t check for repeats before posting inserts.

Window functions turned this grouping process into a more natural part of SQL. A PARTITION BY clause inside a window function forms a boundary around matching rows. Clusters become independent zones where row numbering, sorting, and filtering happen without pulling in unrelated data. That’s helpful for tables where thousands of rows share the same match columns, because the grouping happens inside the engine instead of through a series of joins or application round trips.

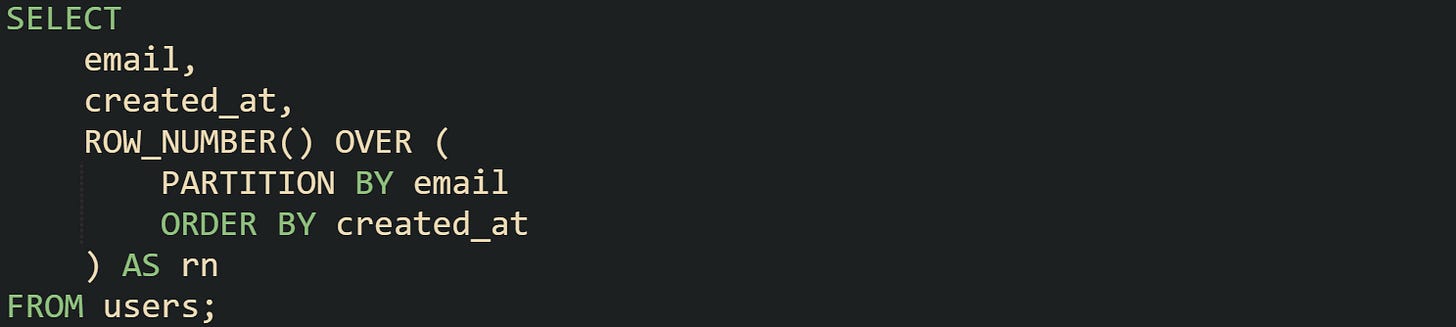

This query gives a ranked list inside each bucket of matching emails. Databases perform the partitioning and sorting within one operation, which keeps the entire cluster view intact during the scan.

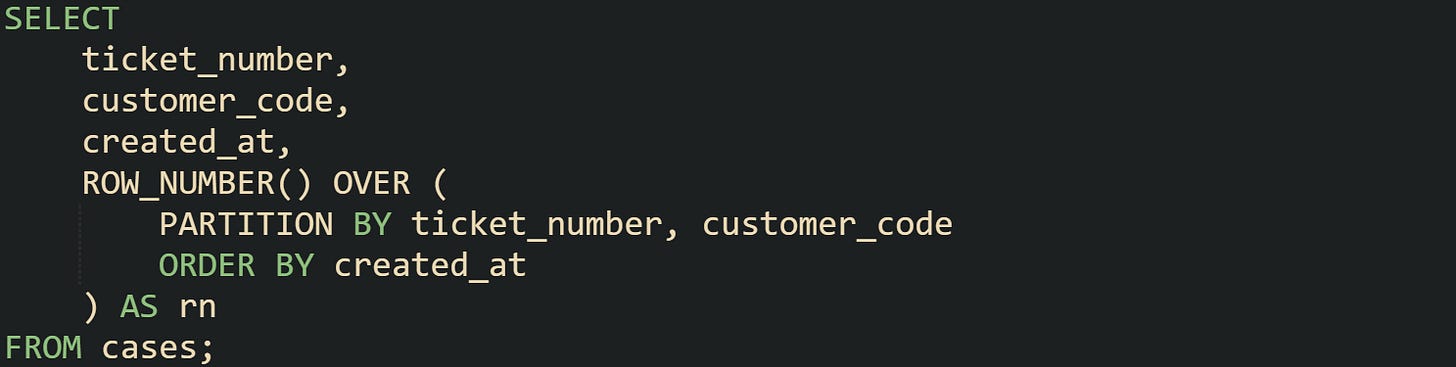

Some systems track support cases and assign a numeric ticket that sometimes gets duplicated during a busy import. In that environment, row identity could depend on ticket number and customer code. Take this for example:

This keeps matching tickets grouped by customer and forms a ranking inside each group.

How Window Ranking Keeps Control

ROW_NUMBER() is the tool most people reach for when they want one survivor from a cluster of duplicates. Ranking removes the guesswork by creating a stable number for every row in the cluster. The sort order drives which row comes first. That decision depends on the table. Some columns show recency through timestamps. Others show natural order through numeric identifiers that track how rows entered the system.

Window ranking can produce a single row when the rest need to be flagged for deletion. Modern engines can filter on the ranking in outer queries, which gives a smooth way to act on rows without extra subqueries or hand built counters.

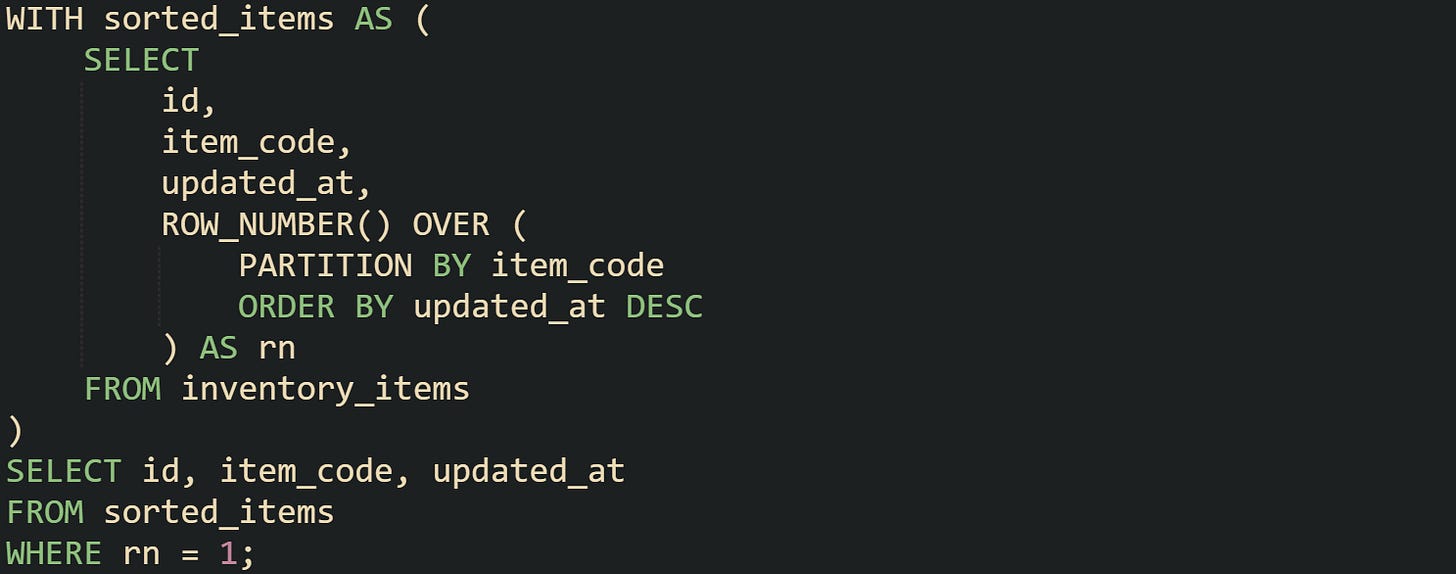

This returns one row for each item code, keeping the most recent timestamp for that group. A separate delete step can then target the rows where rn is greater than one. Ranking makes it practical to build very precise filters, because the rank gives a dependable indicator of which row stays.

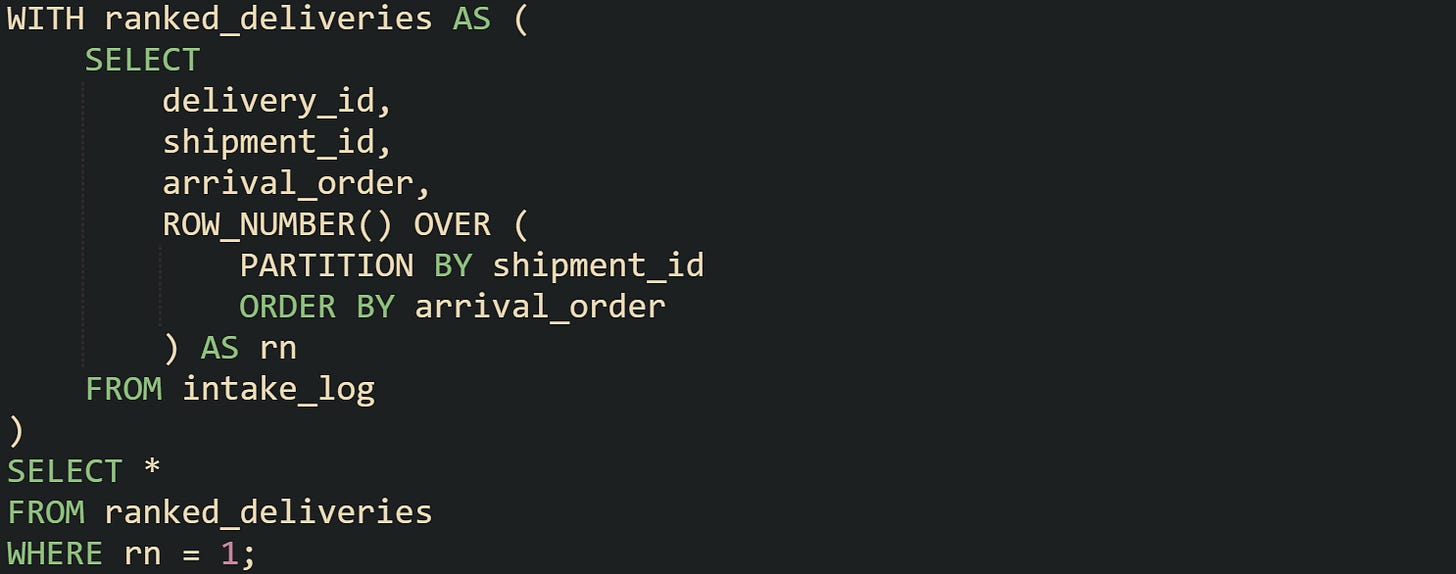

Some tables benefit from a slightly different sort order. Delivery logs usually track incoming drop offs with an arrival_order column where lower values reflect earlier processing. Sorting by that column creates a reliable tie breaker for clusters.

Queries like this keep one delivery record per shipment based on the earliest arrival order.

When GROUP BY Fits Better

Grouping handles a different class of duplicates. Some tables don’t have timestamps or identifiers that create a meaningful sort order. Others hold values that repeated many times in ways that carry no special meaning for choosing a survivor. In these cases, a cluster can collapse down to one row through a grouped projection where aggregate functions keep the fields that matter. Group rebuilding reshapes the table into a list of distinct groups where every group returns one row. You can control which columns appear in the result and choose how they aggregate. Fields without variation across the cluster can sit in the GROUP BY list without an aggregate. Fields with variation, such as timestamps or status codes, can be merged with aggregates such as MIN or MAX.

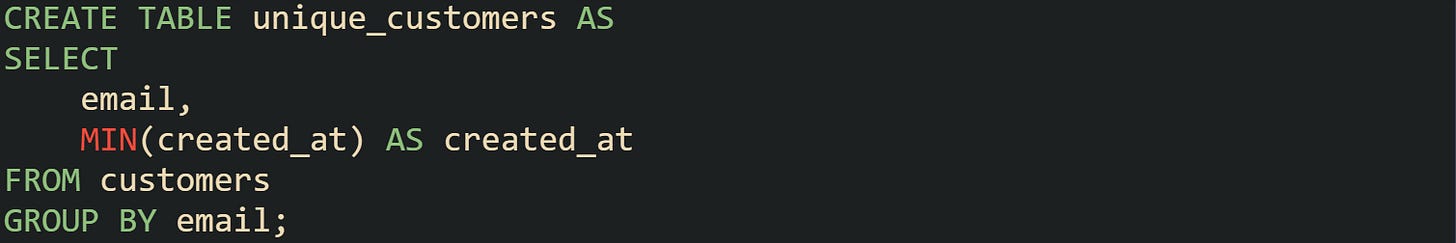

This creates a compact table where each email appears once and the earliest timestamp stays attached. Some teams then refresh the original table from the grouped version to restore a tidy dataset.

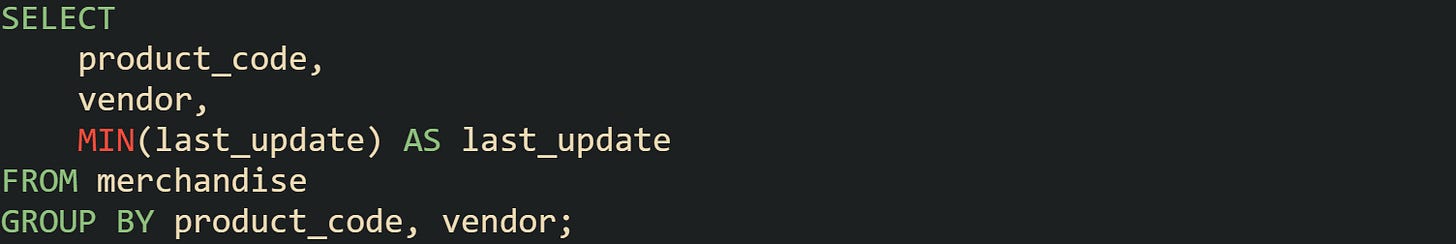

Merchandise tables may carry repeated rows when imports ran twice during an outage. Those rows hold the same product code and vendor, but they may differ in an update field that carries no lasting value. A grouped version of the table can be constructed where product and vendor define the group and the earliest update stays.

Grouping fits naturally for tables where duplicate rows are true clones aside from one or two fields that never needed repetition. It reshapes the data into a single set where every cluster shrinks to one row without ranking or tie breakers.

Controlling Which Row Survives

Removing duplicates turns into a real solution only when there’s confidence about the row that stays. Databases can rank, sort, or group duplicate clusters, but the final choice still comes down to how well the table’s structure hints at which record stands as the right one. Some tables track history through timestamps, others track creation order through identifiers, and some don’t carry meaningful order at all.

Picking a Survivor with Window Sorting

Window functions give precise control when duplicate clusters carry small differences that matter. Sorting inside the window defines which row rises to the first position. That sort order can follow timestamps, numeric identifiers, or any column that expresses natural order within the data set. Engineers rely on ROW_NUMBER() because it labels every record in the cluster in a predictable way, forming a numbered view that can be filtered without breaking the cluster structure.

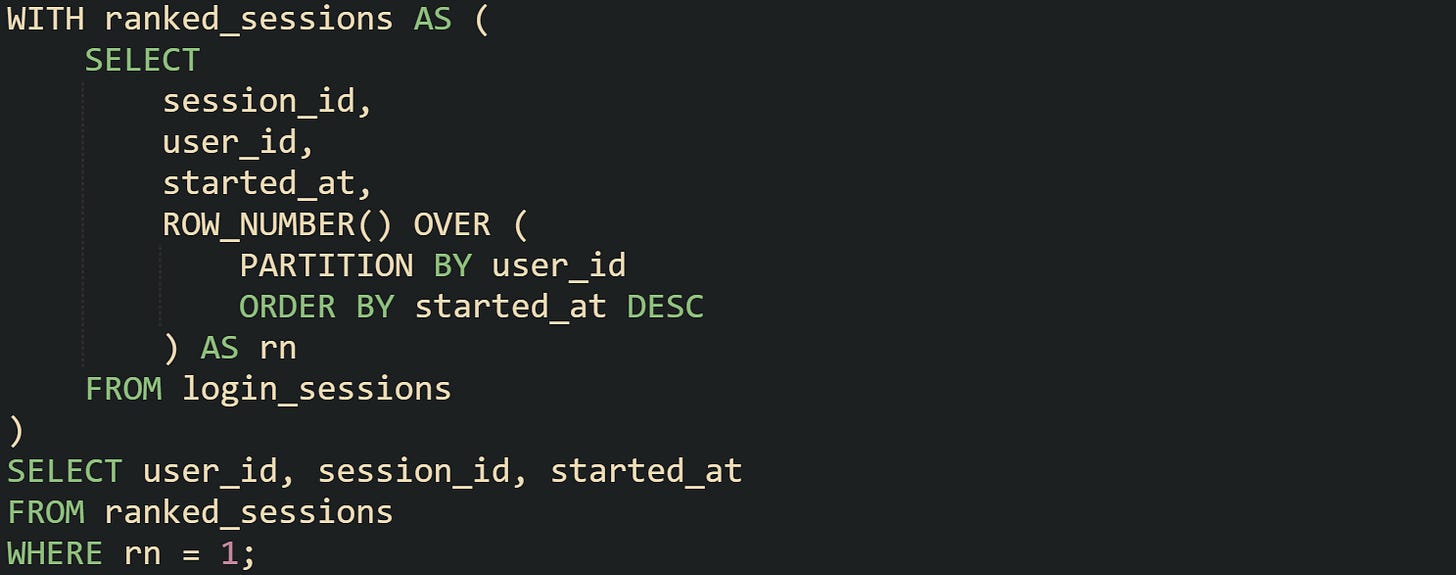

This keeps the most recent session for every user based on the timestamp column. Tables with repeated imports of user activity benefit from this view because the latest timestamp tracks the true current state.

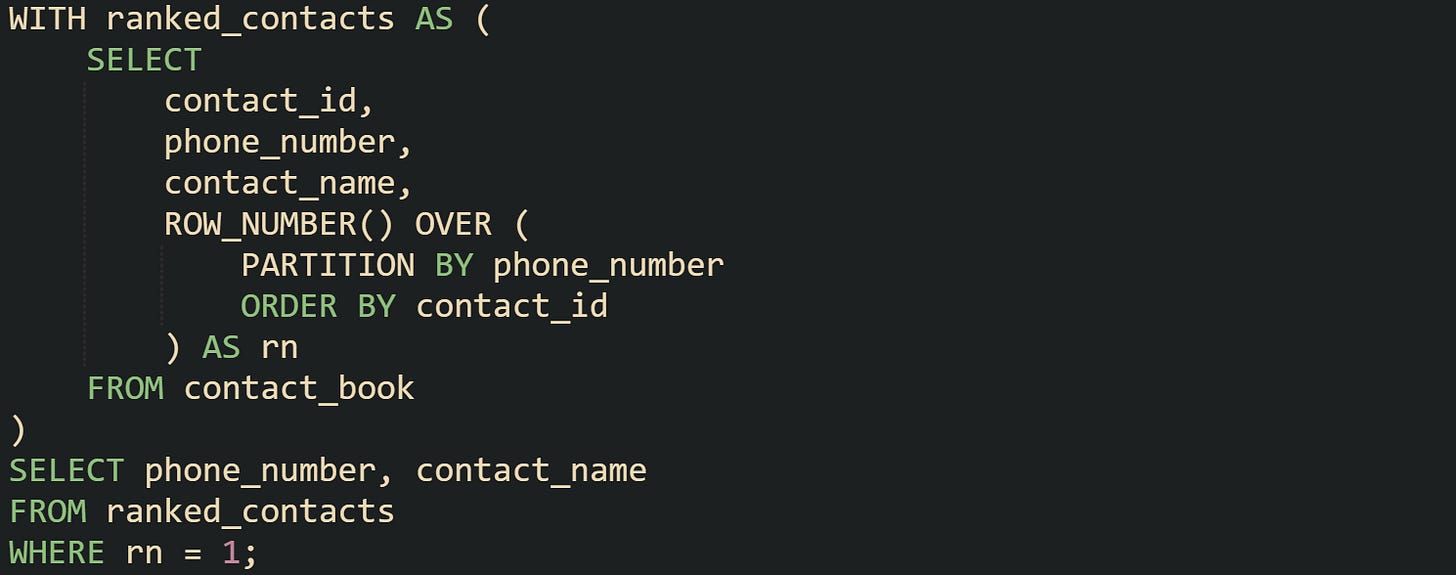

Some tables rely on integer identifiers instead. A contact list might assign incrementing values to rows as they enter the system, where lower values reflect earlier inserts. Ranking by that identifier can give a stable choice for clusters.

This returns the earliest captured record for each phone number based on the smallest identifier in the cluster. Systems that store rows from periodic uploads sometimes prefer the earliest value rather than the newest, because the earliest row reflects the original imported state.

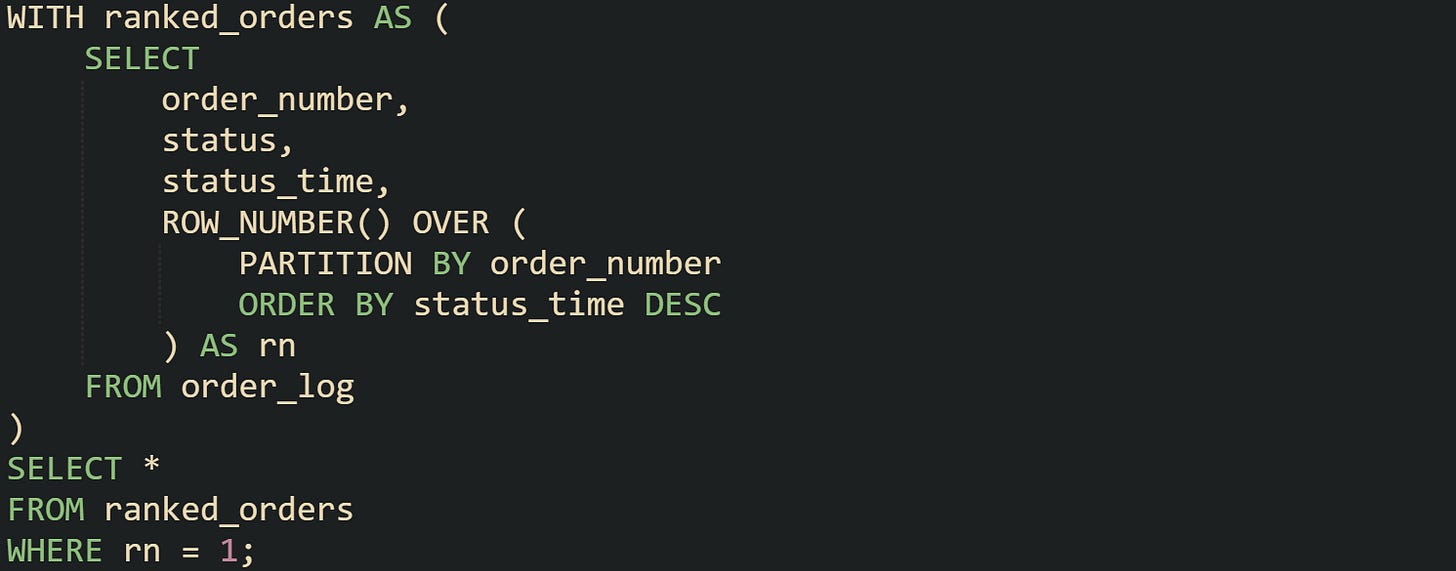

Another case can be in order logs that record repeated entries for the same order number during retries. Sorting by a status timestamp marks the moment a row was last updated.

This returns the most current order entry based on the freshest status time. Ranking gives a dependable filter that can be applied to dozens or hundreds of clusters without custom logic.

Rebuilding a Table with Group Aggregates

Group aggregation belongs to situations where duplicate clusters carry no meaningful internal differences or where the table’s structure doesn’t provide a natural ordering column. Group rebuilding forms a compact version of the table where matching fields define a cluster and aggregate functions refine any fields that vary between duplicates. Fields that never vary within a cluster can remain as ordinary columns without aggregation.

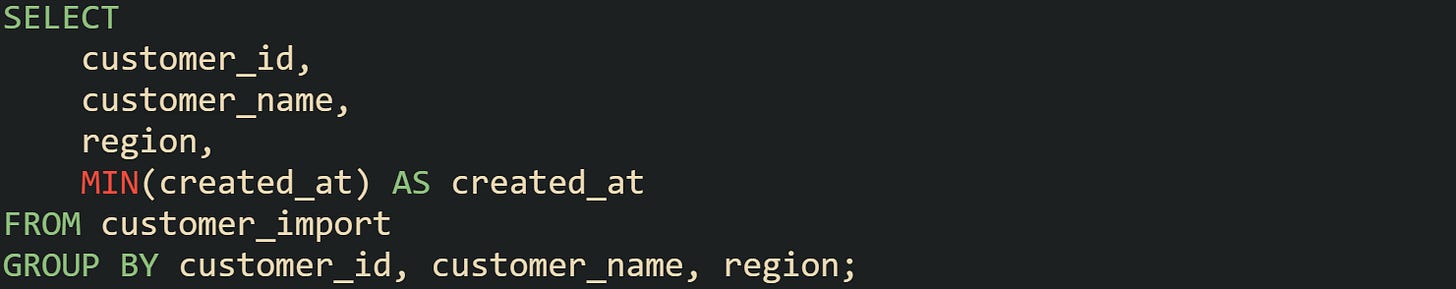

Some customer data imports repeat rows multiple times when a vendor system exports the same record without checks. Those records share an identifier, name, and region but differ in the moment they were recorded.

This keeps the earliest timestamp for a customer. Systems with flat import cycles sometimes want the first recorded time because it represents the original presence of the customer in the system.

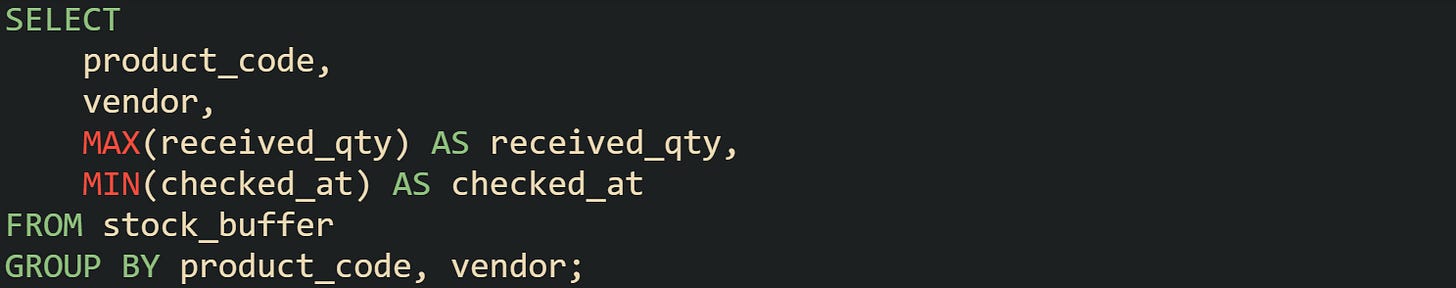

Inventory tables occasionally repeat entries for the same product during syncing. Those entries tend to match in product code and vendor while one or two housekeeping columns vary in unhelpful ways. Group aggregation trims those clusters while keeping relevant fields intact.

This version keeps the highest recorded quantity and the earliest check time for every product and vendor pair. Some stores track updates through rolling imports where quantities fluctuate until the run completes, so a grouped pass gives a stable view without duplicate clutter.

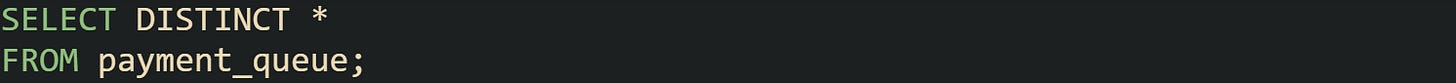

There are moments when grouping doesn’t need aggregates at all because the duplicate rows match in every column. That happens during bulk inserts when identical values enter through repeated jobs.

This quick projection strips identical rows without extra computation, though it doesn’t work for clusters where fields vary. Grouping stays more flexible for those cases, forming a controlled rewrite of the table where clusters shrink to stable single rows under rules that match the data’s purpose.

Conclusion

Good dedup work comes from seeing how a database groups rows, ranks them, or rebuilds them into stable clusters. Window functions give a steady hand when a clear order exists inside the data, and grouping steps handle clusters that share the same fields without any helpful ordering clues. The two methods rely on mechanics that stay predictable across engines, so once the match columns are set, the rest of the process stays grounded. Removing duplicates while keeping one dependable record becomes a natural part of shaping a table that stays tidy and accurate for whatever comes next.