Pointer conversions with Go’s unsafe package sit right at the edge of what the compiler guards and what developers can stretch. The language was built with strong memory safety rules, but unsafe opens a narrow door to direct pointer manipulation. That door allows tricks that sidestep normal typing checks, though it always comes with a trade-off in safety.

Mechanics of Unsafe Pointers

Working with unsafe pointers in Go means stepping outside the usual guarantees that the compiler provides. Normally, pointer types are strict, which keeps a strong separation between an *int and an *string. That structure prevents errors and keeps memory access predictable. With unsafe.Pointer, the compiler relaxes these rules and allows conversions that ignore type checks. It’s a thin type that carries no information about what the pointer actually refers to, making it a gateway for moving between raw addresses and typed pointers.

Conversions Allowed in Unsafe

The unsafe docs list a small set of valid patterns. Code outside those patterns can still compile but is invalid and can break at run time. That boundary is strict, but the conversions it does allow are flexible enough to completely bypass type safety.

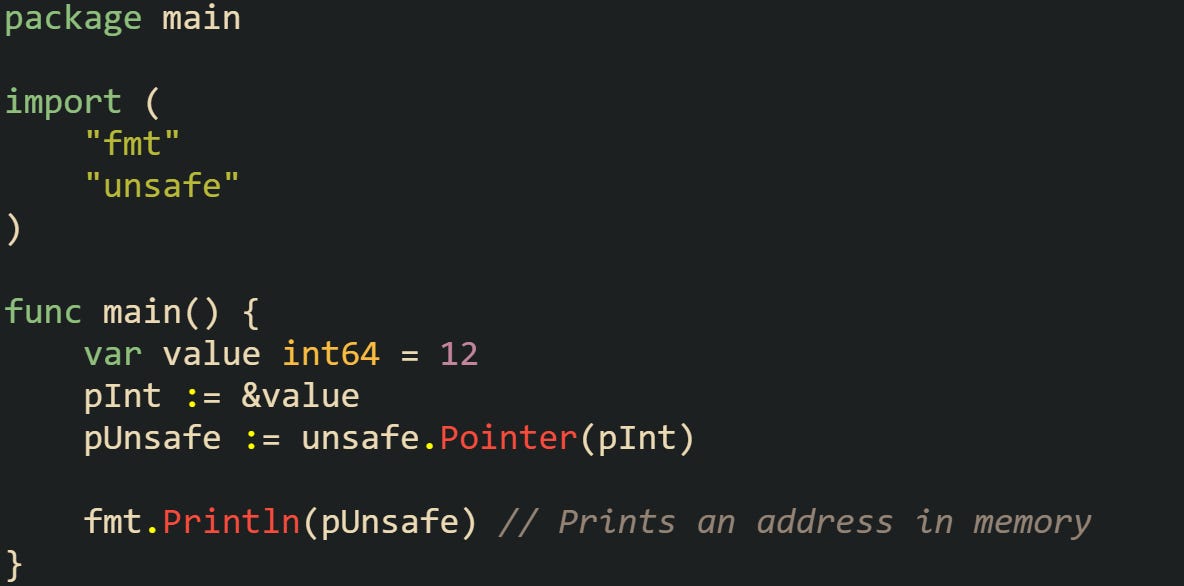

One common pattern is converting a typed pointer to unsafe.Pointer. This lets you strip away the type and handle the raw address instead:

When converted, the compiler doesn’t track that this pointer originally referred to an integer. That same unsafe.Pointer can be reinterpreted as something entirely different.

What happens here depends entirely on how the bits align between types. The runtime does nothing to stop you, and the compiler assumes you know what you’re doing.

Another conversion permitted is moving between unsafe.Pointer and uintptr. A uintptr is just an integer big enough to hold an address. By converting a pointer to uintptr, arithmetic on addresses becomes possible. Afterward, you can convert back to unsafe.Pointer and then to a typed pointer. This isn’t something you could ever do with normal typed pointers.

Memory Safety Breakage

The flexibility of unsafe pointers comes at the expense of memory safety. The Go runtime can’t protect you when you reinterpret data incorrectly or when pointer arithmetic runs past the actual object. Reading a chunk of memory as the wrong type doesn’t raise an error by itself, and the result is unpredictable.

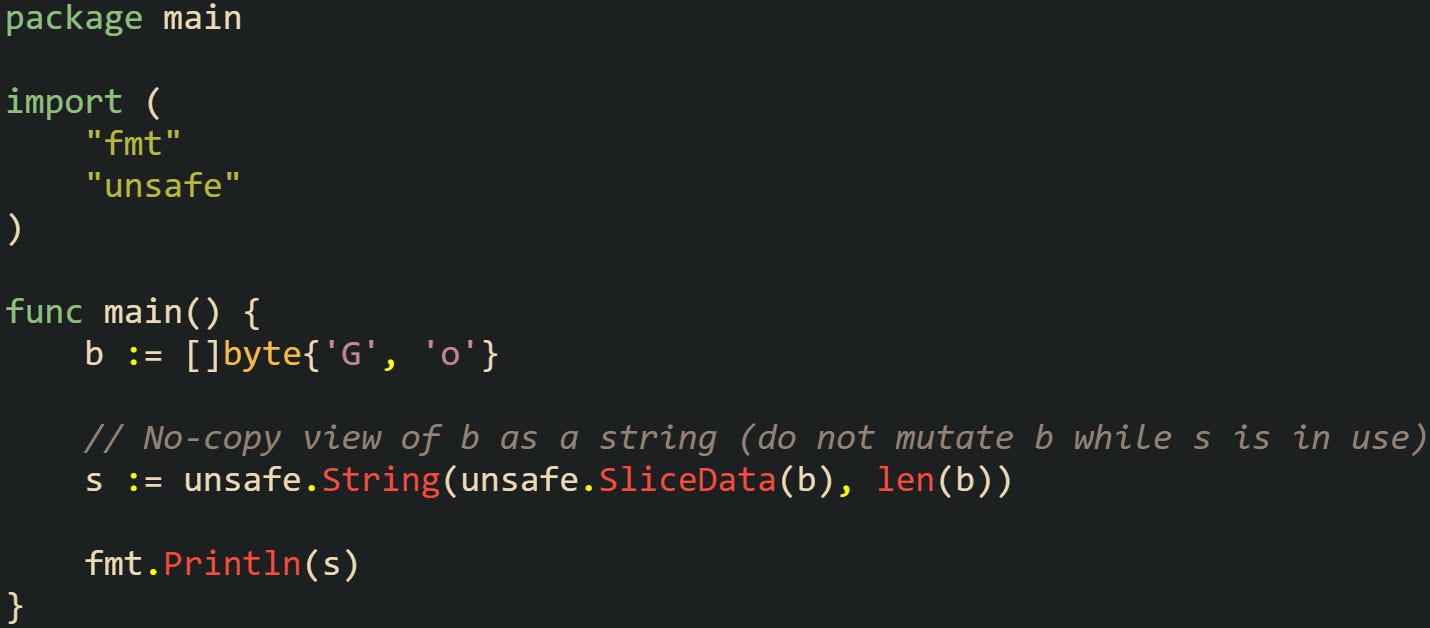

Converting a []byte header to a string header by reinterpreting &b is not valid. Slices and strings use different header layouts, so the cast isn’t supported. If you need a no-copy string view, use unsafe.String(unsafe.SliceData(b), len(b)) and never mutate the bytes while that string is in use.

This works because the string’s header points at the same backing bytes as the slice. The string must be treated as read-only.

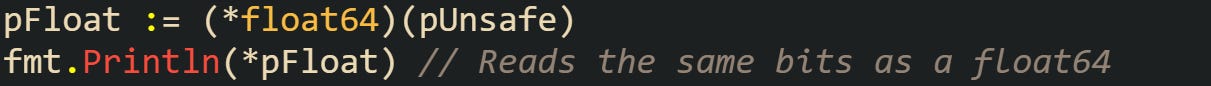

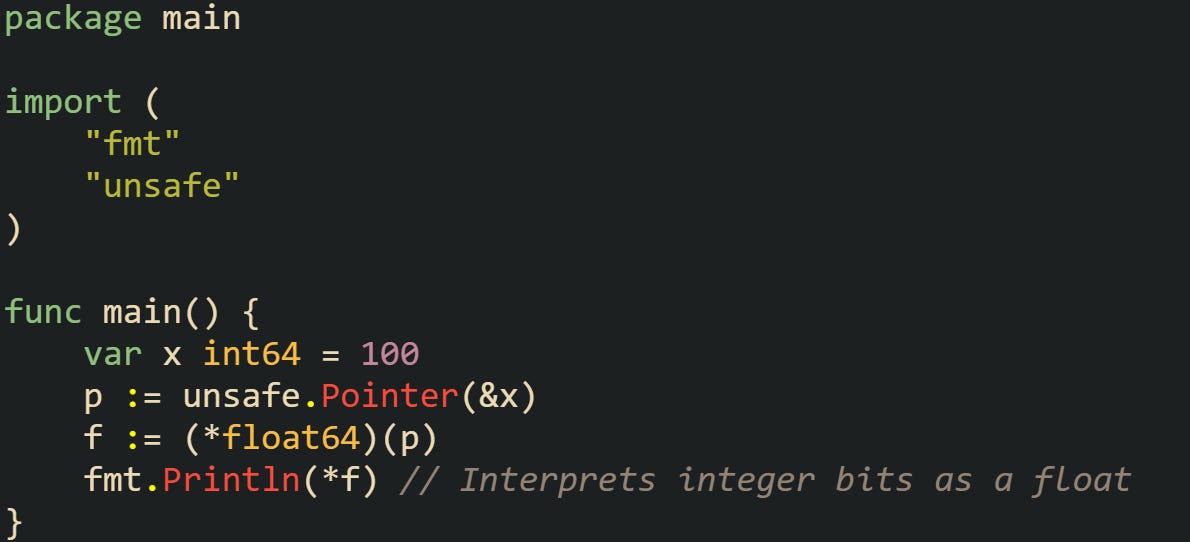

Reinterpreting integers as floats can cause similar trouble. Writing into memory as an integer and then reading it as a floating-point number only reuses the same 64 bits, it doesn’t convert them.

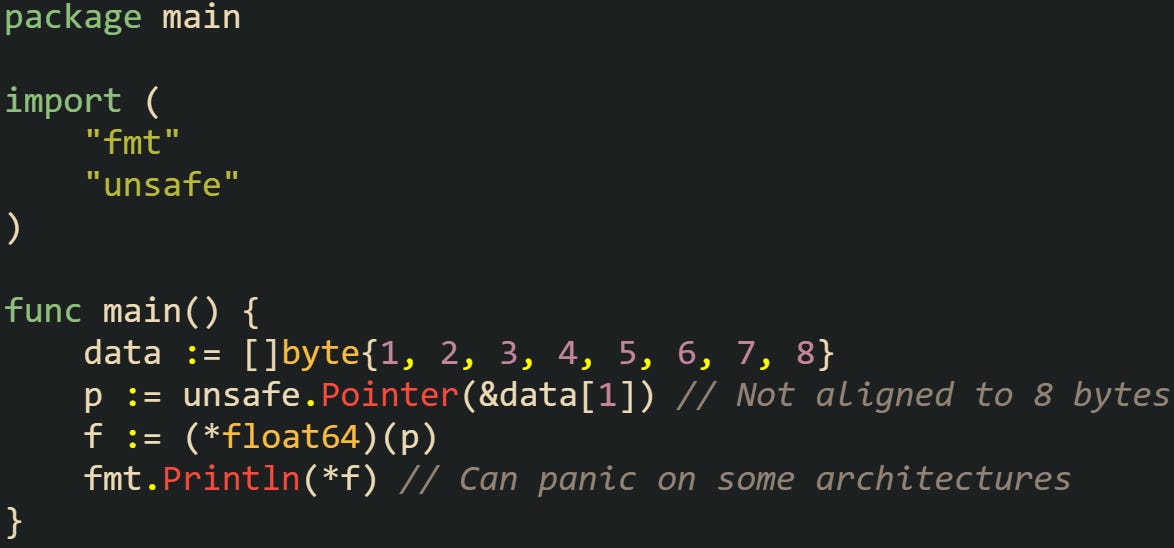

The output depends on the bit pattern and alignment rules on the target CPU. Misaligned access and bad offsets can trigger runtime panics on some systems. Reading a float64 from a non-8-byte-aligned address is enough to crash on certain architectures. These hazards don’t appear in safe Go, but they surface quickly once unsafe is involved.

Why uintptr Matters

The bridge between typed pointers and unsafe pointer tricks is uintptr. Unlike unsafe.Pointer, which the garbage collector understands as a pointer, uintptr is just a number. That difference makes it possible to perform arithmetic on addresses but also introduces hazards if not handled with care.

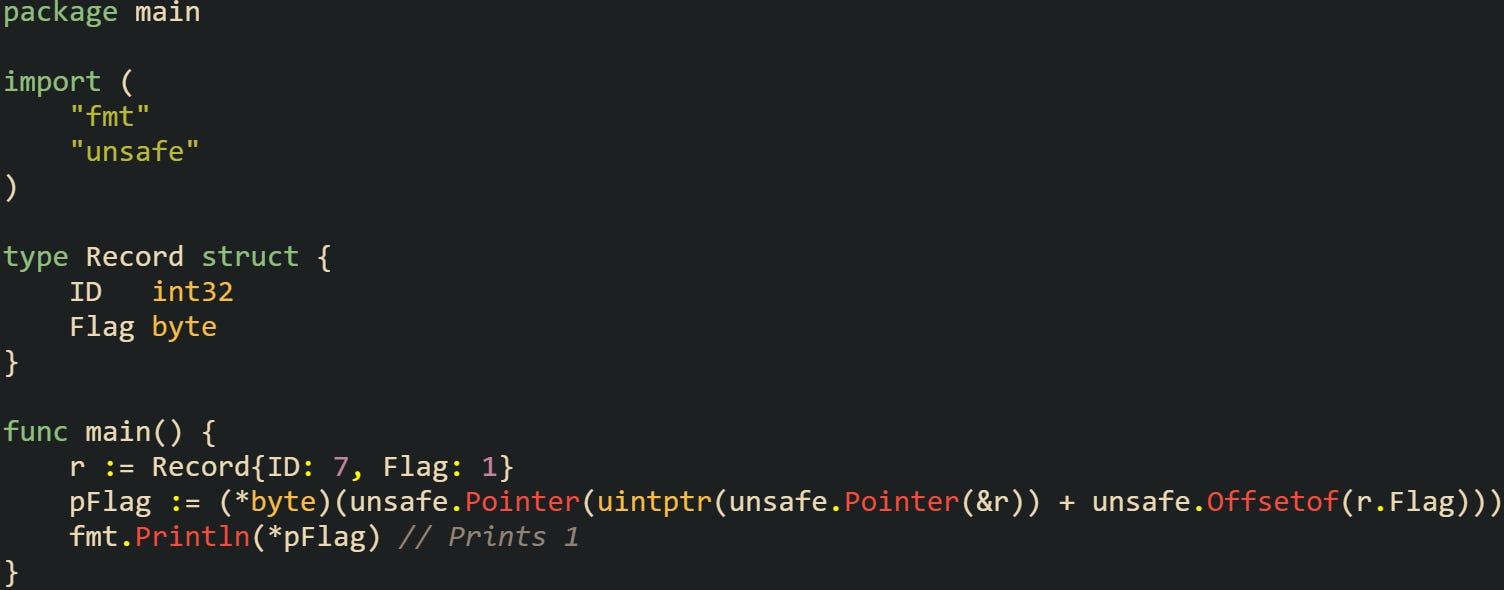

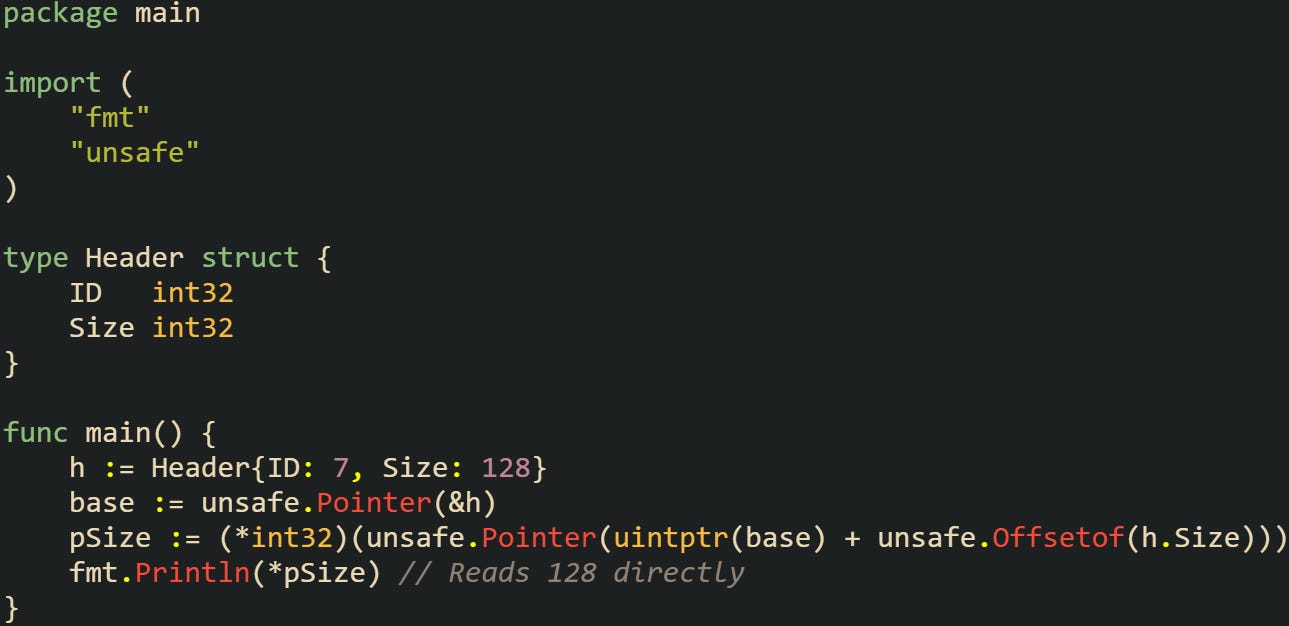

uintptr is often used with unsafe.Offsetof, which provides the byte offset of a struct field. Adding that offset to the base pointer lets you compute the address of the field manually.

uintptr provides a way to step through memory layouts. Instead of relying on Go’s field access, you can calculate addresses yourself. The compiler doesn’t normally allow this because it can lead to misaligned or invalid reads.

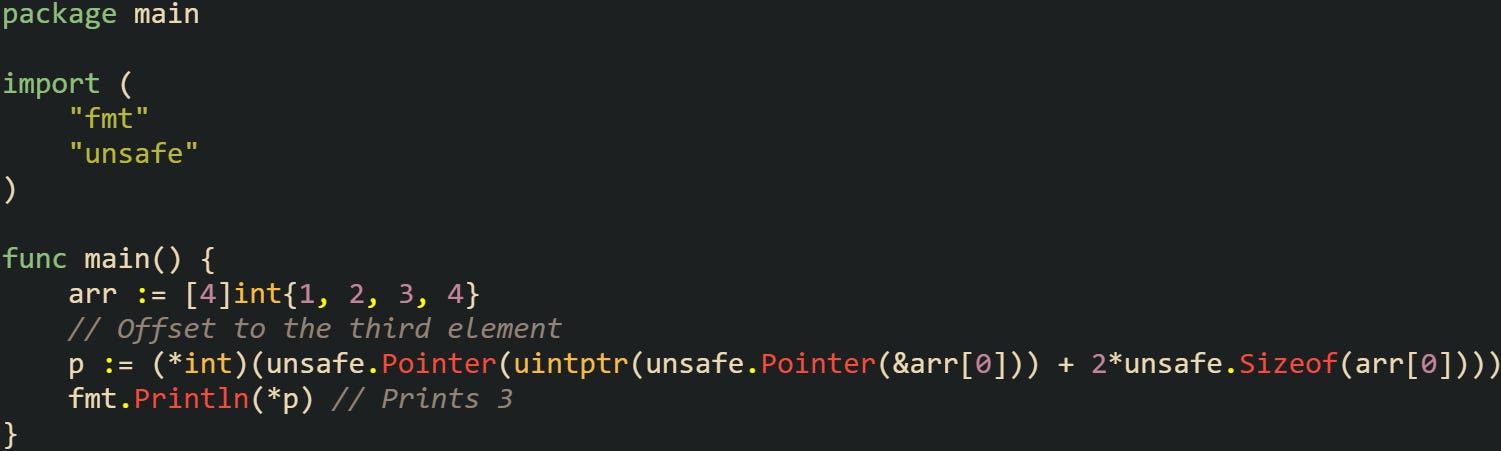

You can also manipulate slices in unsafe ways with uintptr. By computing addresses manually, you can step outside the boundaries enforced by safe code.

The third element is accessed by offsetting two element sizes from the start. This arithmetic works fine here, but nothing stops you from walking off the edge of the array. The runtime doesn’t protect this case, which is why it’s easy to land in undefined behavior territory.

The existence of uintptr makes unsafe pointer conversions far more flexible. It’s the tool that allows not just type reinterpretation but actual address arithmetic, turning pointers into navigable offsets. The price, however, is that once a pointer becomes a plain integer, the garbage collector no longer recognizes it. If that integer is stored away while the original pointer is gone, the garbage collector may free the object, leaving a dangling address behind.

Safety Concerns and Alternatives

Unsafe pointers bring flexibility at the cost of reliability. Code that relies on them gains access to memory in ways the compiler doesn’t normally allow, but that access comes with hazards. Some risks are subtle, tied to how hardware enforces alignment, while others stem from how the Go garbage collector manages memory. There are also cases where unsafe pointers have been adopted in practice, though always with a narrow scope. Modern Go offers features that cover many of the use cases that once required unsafe conversions, which means the need for unsafe code has become more limited over time.

Risks in Real Programs

The biggest danger with unsafe pointers comes from their ability to bypass the checks that normally keep memory operations valid. One recurring issue is alignment. Certain CPU architectures won’t allow a type like float64 to be read from an address that isn’t a multiple of eight bytes.

This panic doesn’t happen on every machine, which makes the bug unpredictable. Code that passes on one system could crash on another.

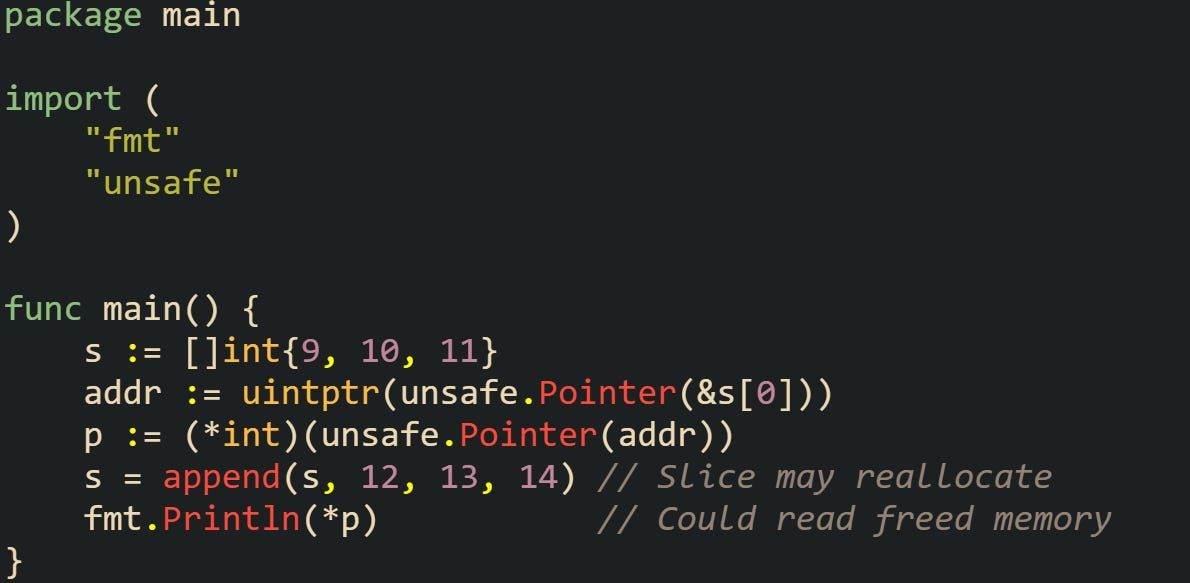

Garbage collector interaction introduces another hazard when arithmetic with uintptr is involved. While a typed pointer keeps the object alive, converting it into a raw number removes that protection. If the program later resizes or reallocates memory, the saved numeric address may no longer point to valid data.

This may look harmless, but if the slice reallocates, the old address no longer points to valid memory. That risk is invisible in normal Go, but it becomes very real with unsafe conversions.

Approved Use Cases

Even with the risks, unsafe pointers have their place. The Go runtime itself uses them in tight loops and low-level operations where performance and direct memory control are unavoidable. The same is true for some standard library features.

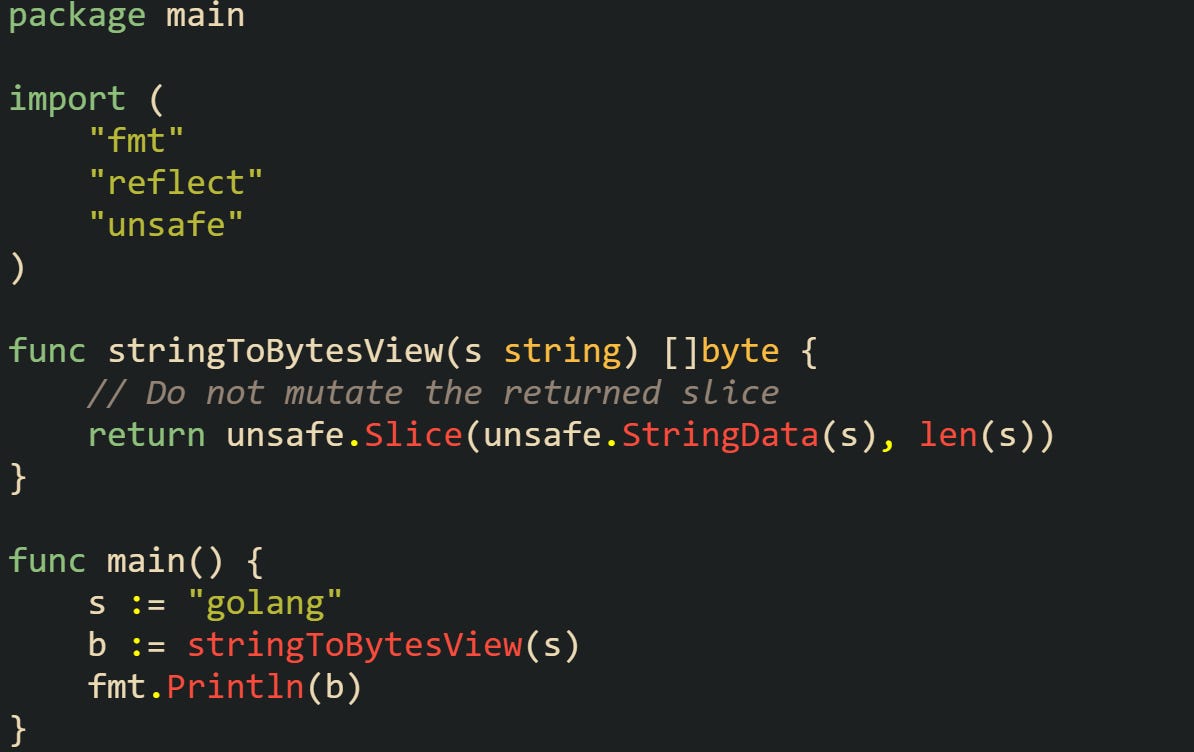

One widely known case is fast conversion between a string and a byte slice. Normally, converting a string to []byte creates a new slice with a copy of the data. Unsafe tricks can skip the copy and point the slice directly at the string’s memory.

This avoids allocation and copying, but it also breaks the immutability rule of strings. Modifying the slice would corrupt the string, so it has to be treated as read-only.

Reflection is another place where unsafe comes into play. Accessing struct fields by offset is faster with unsafe arithmetic than with higher-level reflection calls. The reflect package itself relies on unsafe operations to provide its field access functions.

This method is reserved for performance-sensitive libraries where reflection overhead would be too heavy. For everyday code, the standard field access is safer and easier to maintain.

Safer Alternatives

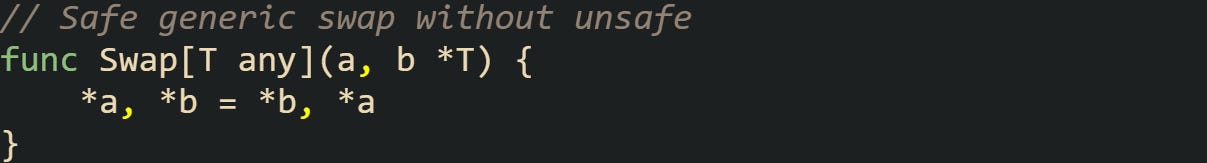

Modern Go has introduced ways to reduce the need for unsafe operations. Generics in Go 1.18 allow developers to write type-agnostic code without falling back to unsafe tricks. Many unsafe patterns were workarounds for the lack of generic functions, and now those patterns can be replaced with safer code.

Before generics, swapping values of an arbitrary type often relied on unsafe conversions, but now the language provides a clean, safe solution.

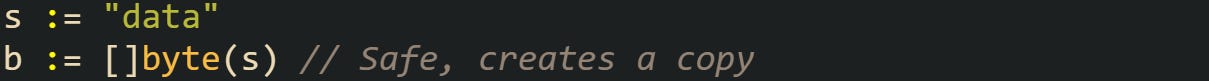

Another safer alternative is to rely on built-in copy and conversion functions. Converting a string to a slice of bytes without unsafe makes a copy but avoids all risks of data corruption.

The copy costs memory and time, but it guarantees that modifying the slice won’t corrupt the original string. For most applications, that trade-off is worthwhile.

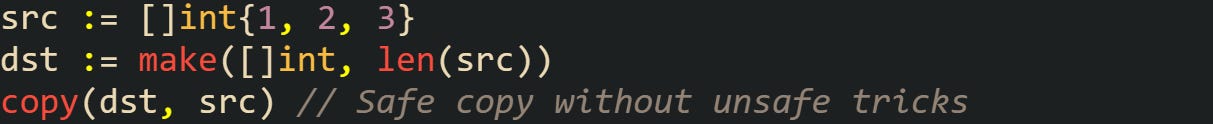

Slice functions like copy also provide safer memory movement compared to manually computing addresses with unsafe pointers.

These built-ins handle alignment, bounds, and garbage collector visibility. They may not match the raw performance of unsafe tricks, but they keep programs reliable across platforms and future Go releases.

General Recommendation

Unsafe pointer conversions remain part of the language, but their use is best limited to libraries and runtime code that absolutely require them. For most development, safer alternatives exist that balance performance with memory safety. Code that leans on unsafe is harder to port, more fragile, and more likely to fail in surprising ways. Modern Go continues to evolve in ways that reduce the need for unsafe, so developers have fewer reasons to reach for it today than in earlier versions of the language.

Conclusion

Pointer conversions in Go through the unsafe package hinge on a small set of rules that let developers reinterpret memory or calculate addresses directly. Those mechanics explain both their usefulness and their danger. Typed pointers can be stripped to unsafe.Pointer, turned into uintptr for arithmetic, and then rebuilt into another typed pointer. Each step works because the compiler gives up type safety once unsafe is involved. That freedom lets developers reach into memory layouts in ways normal Go code never could, but it also means stepping outside the protection of alignment checks, garbage collection tracking, and type guarantees. For everyday development, the safer built-in features of the language usually provide what’s needed, leaving unsafe pointers as a tool reserved for rare cases where raw access to memory mechanics is unavoidable.