involve checking if related rows exist before deciding which records to keep in the results. The EXISTS operator does this efficiently by asking only one question, does at least one match exist? It doesn’t need to count or combine rows, it only needs to confirm their presence. Developers sometimes write the same check with IN or a JOIN, but those use very different mechanics behind the scenes.

How EXISTS Works in SQL Queries

The EXISTS operator evaluates whether related rows are present in a subquery. Instead of producing a value, it produces a true or false result. That difference is important, because it changes how the database engine treats the query and how much work is required. Where IN collects values and JOIN merges rows, EXISTS only cares about confirming presence.

Basic Form of EXISTS

The pattern always involves a subquery that ties back to the outer query. That connection is made through a column reference.

Each user is checked against the logins table. If at least one login is found, the user qualifies. The inner query doesn’t need to output any actual data. The database discards the content and only uses the fact that a row exists.

You can add conditions to the subquery to refine the check. If the interest is users who logged in during the past week, the same pattern still works:

The addition of a date filter limits which rows count as a match. This makes EXISTS flexible without changing its mechanics.

Why EXISTS Stops Early

One of the reasons EXISTS is efficient lies in how it evaluates. The database doesn’t need every row that matches. The moment a single qualifying row is located, the test passes and the inner query halts.

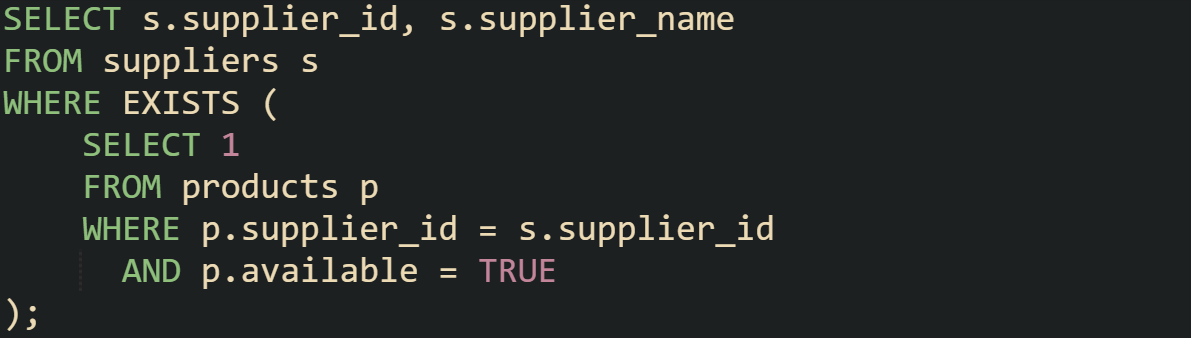

Consider suppliers and the products they sell:

If a supplier has thousands of products, the database doesn’t check them all. It stops after the first available product is found. That early stop keeps the query focused on presence rather than volume. The same behavior applies even when you write the subquery differently. Whether you use SELECT 1, SELECT *, or even a constant expression, the result is the same because only existence matters.

Comparing EXISTS with IN

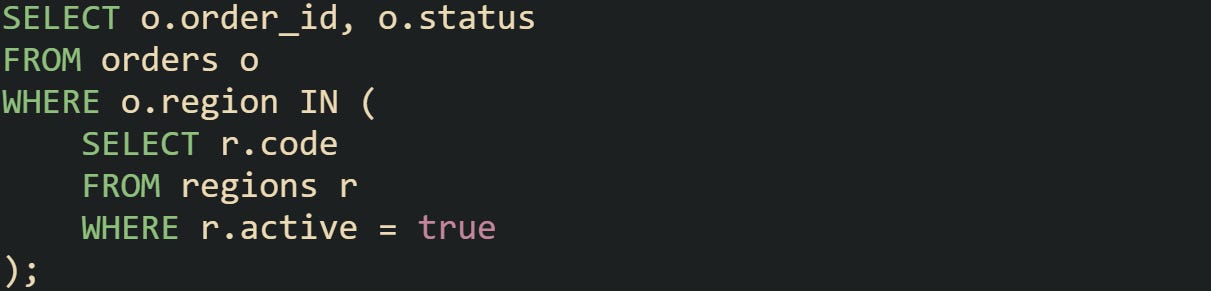

It’s common to see queries written with IN that look like they could be expressed with EXISTS. Both can filter rows based on a related set, but they go about it differently.

IN doesn’t always build a full list of IDs. On many engines the planner rewrites it to probe an index or build a small hash table of distinct values, which avoids extra work on duplicates. The gap between IN and EXISTS depends on the plan.

Optimizers often turn IN subqueries into a semi join, so they don’t need to materialize the whole set first. EXISTS keeps the yes/no test and can short-circuit on the first match, IN is often executed as a semi join or hash probe.

There are also cases where IN is a natural fit. If the query is filtering by a small reference table, then IN feels simple and is usually fast.

The choice often depends on the relationship. When it’s a one-to-many correlation, EXISTS tends to line up more directly with what’s being asked.

Comparing EXISTS with JOIN

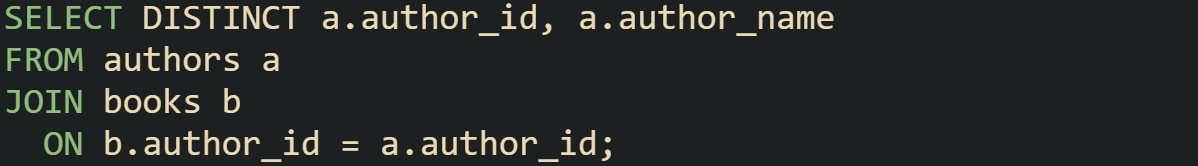

Joins can also be used to answer the question of related rows, but the mechanics are different. A join physically merges rows from two tables into a new result set.

This returns authors with at least one book. The join produces one row per book, which means authors with many books appear multiple times. Adding DISTINCT removes duplicates, but that’s an extra step that requires more processing.

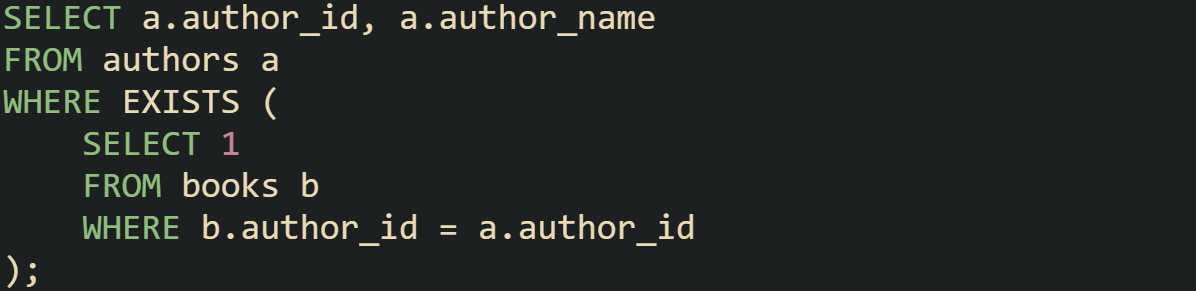

With EXISTS, the query focuses only on the yes or no check:

The result looks the same but is achieved without inflating rows. This makes EXISTS a better match when the requirement is simply to check for presence.

There are times when joins are preferable, such as when you also want details from the related table. For instance, pulling the book title along with the author requires a join, because EXISTS doesn’t return data from the inner query. The distinction is that joins merge data, while EXISTS checks conditions.

Mechanics Behind EXISTS and Performance Differences

The way EXISTS interacts with the database engine is different from operators that build lists or joins that merge rows. Its efficiency comes from how query planners treat it as a true or false check rather than a data-producing clause. That small shift changes how indexes are used, how execution plans are shaped, and how much work is avoided during evaluation.

Correlated Subqueries and Indexes

Most EXISTS clauses use a correlated subquery, which means the inner query ties directly to a value from the outer query. That connection is where indexes can make a large difference. When a column referenced in the subquery is indexed, the database doesn’t need to scan the entire table. Instead, it performs quick lookups to see if at least one match exists.

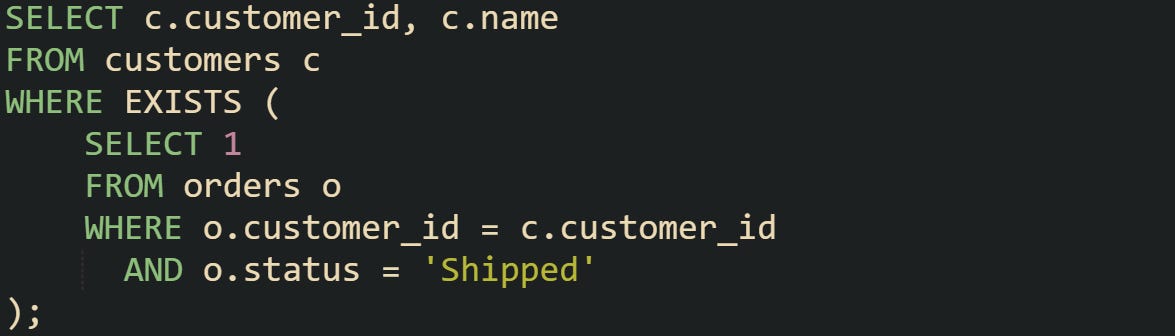

If orders.customer_id has an index, the query plan often becomes a nested loop that probes the index for every customer. Each probe stops at the first shipped order found. Without an index, the engine scans the whole table, which is less efficient as the number of rows grows.

Short Circuiting in Execution

The evaluation of EXISTS benefits from short circuiting. The moment the inner query produces a row, the engine treats the condition as satisfied and stops checking further rows. That’s why the actual value in SELECT 1 or SELECT * doesn’t matter.

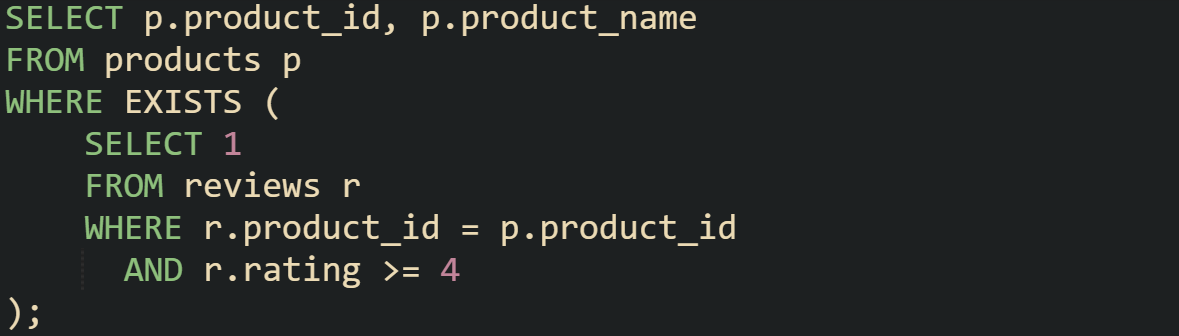

When a product has hundreds of reviews, the database doesn’t need to scan through them all to decide if one has a rating of four or above. As soon as the first qualifying review is seen, the subquery exits. This early stop is what gives EXISTS a lighter footprint than approaches that gather full result sets.

When IN May Perform Similarly

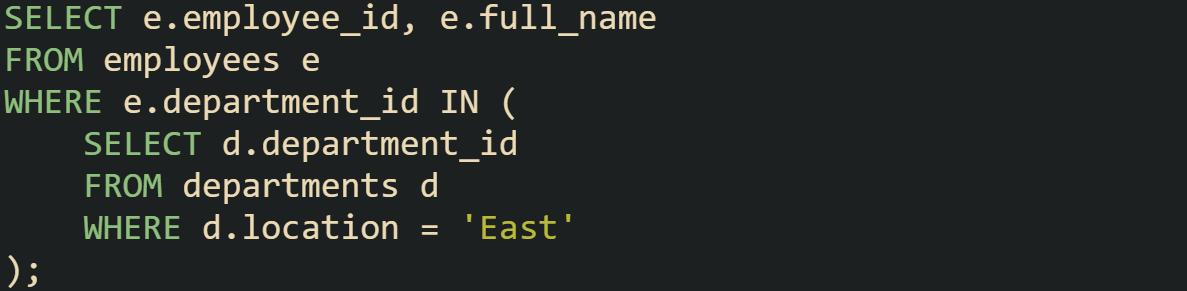

Some queries that use IN perform almost the same as EXISTS, especially when the subquery returns a small and distinct set of values. Query optimizers in modern systems are often smart enough to rewrite simple IN clauses into execution plans that mimic the behavior of EXISTS.

Because the departments table is usually much smaller than the employees table, the IN operator doesn’t add much overhead here. The database may cache the small list of department IDs and filter employees against it quickly. But with large or duplicate-heavy subqueries, IN can create more work than EXISTS, which never builds that list in the first place.

Why JOIN is Not a Drop in Replacement

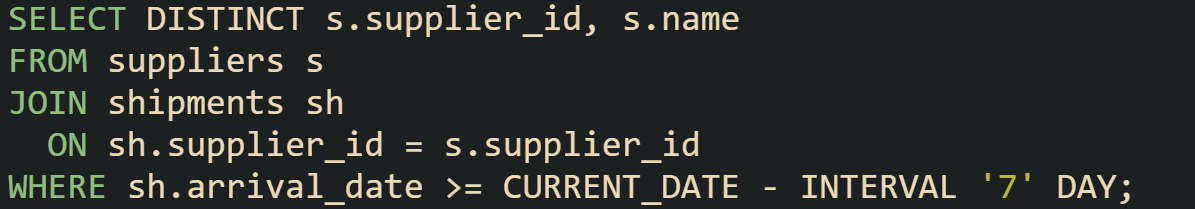

Joins can express similar logic, but they change how results are produced. A join combines rows from two tables into a new set. When multiple matches exist, multiple rows appear. Filtering those down often requires DISTINCT or aggregation.

This query produces one row for every matching shipment. A supplier with ten shipments in the past week will first appear ten times, and only after applying DISTINCT will the duplicates be removed. That extra step means more processing. With EXISTS, the database checks for the presence of at least one shipment row and moves on without multiplying results.

Products and Reviews Example

A product catalog is a straightforward way to see the difference. Suppose the requirement is to list products that have been reviewed.

Both versions return the same list of products, but the work done is not the same. The join first creates one row for every product–review pair, then relies on DISTINCT to compress them. The EXISTS query never creates those extra rows, which makes it a more direct fit when the only requirement is to check if related reviews exist.

There are times when you want to go further than just checking for any review at all. Imagine you only care about products that have at least one review written in the past week. That filter can be written neatly with EXISTS without changing the outer query.

This version preserves the efficiency of EXISTS while adding a temporal condition. The query engine still stops at the first review that meets the date filter, which means it avoids scanning all reviews when a recent one is found early. That makes the operator useful not just for simple existence checks but also for conditions tied to time or other attributes.

Conclusion

The mechanics behind EXISTS make it a strong tool for filtering on related records without unnecessary overhead. It checks for presence, stops the moment a match is found, and avoids row inflation that comes with joins. Compared to IN, it doesn’t need to assemble a full set of values before filtering. That difference in how the database engine treats each option explains why EXISTS often runs leaner and is easier to reason about when the only question is whether related data is there at all.