Working with databases often means gathering data from several related sources in a single query. Subqueries make this possible by placing one query inside another. When they’re placed in a SELECT clause, they can return related values as part of the result for each row. When they’re placed in a WHERE clause, they can filter results based on calculations or matches from other tables. This lets you answer complex questions in a single statement instead of running multiple queries. Subqueries can also work in the FROM clause, creating temporary results that the outer query can use for further filtering or calculations.

Mechanics of Subqueries in SELECT and WHERE

Subqueries are queries that run inside another query, and the result of the inner query is passed back to the outer query as part of the execution process. Their placement in a SELECT or WHERE clause affects how many times they run, what type of value they return, and how the database engine plans the entire statement. When you put one inside SELECT, it behaves like a column whose value is calculated on demand. When it’s in WHERE, it acts as a condition that decides if a row should be included or excluded. The database’s optimizer looks at both queries together to decide the most efficient way to get the final results.

Subqueries in SELECT

Placing a subquery in a SELECT clause lets you return calculated or related data right alongside the main table’s columns. The inner query is linked to the outer one through a correlated condition when it depends on the outer row’s values. This means it often runs for each row in the main result set, unless the database can rewrite it internally for efficiency.

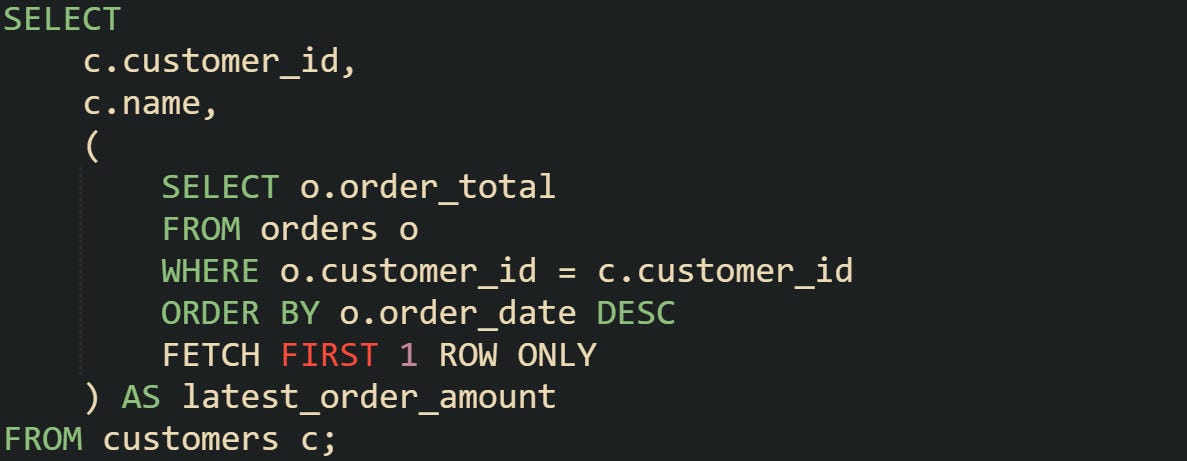

A simple example is showing each customer along with the amount of their most recent order:

First, a customer row is identified from the outer query, then the inner query runs to find the most recent order’s total for that customer.

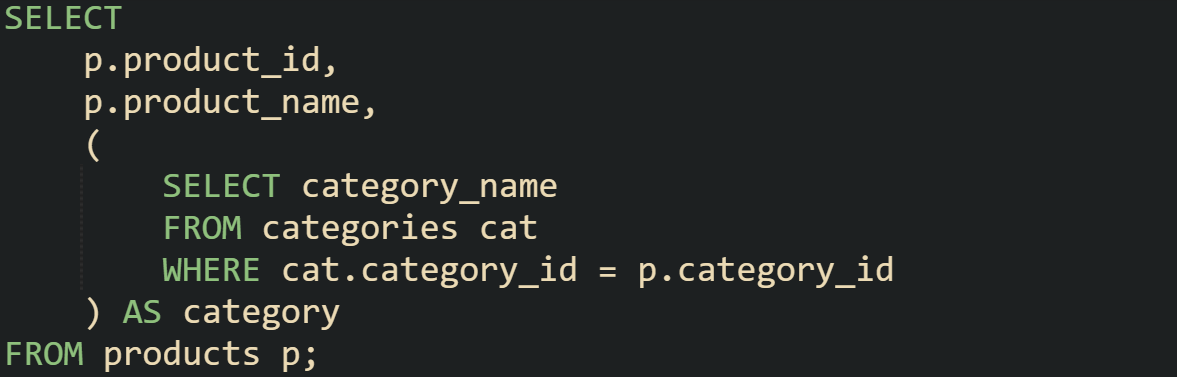

Another useful variation is including data from a completely different but related table without joining:

In this the subquery works like a lookup for each product’s category name. While a join could produce the same result, a subquery can make the intent very clear when you only need a single related value.

Subqueries in WHERE

A subquery in the WHERE clause acts as a condition that filters which rows the outer query returns. It’s evaluated for each row when correlated, or just once when uncorrelated, and the result is compared against the outer row’s values.

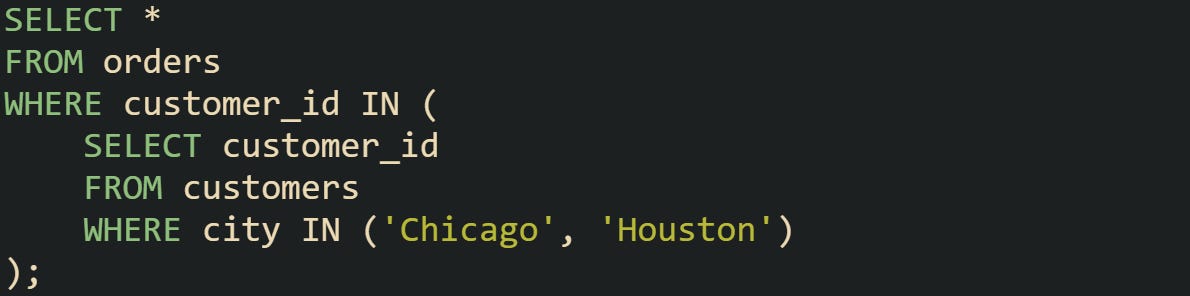

One example is finding orders placed by customers who live in a certain set of cities:

The subquery gets all customer IDs from those cities, and the outer query returns orders for those customers.

How the Database Handles Execution

When a query contains subqueries, the database engine doesn’t simply run the inner one first and then the outer one as if they were two separate statements. Instead, it parses the entire SQL, checks for correlations, evaluates possible execution paths, and picks an execution plan. For uncorrelated subqueries, the result can be computed once and reused for every row in the outer query. For correlated subqueries, the execution depends on the value from the outer row, which means they’re often run repeatedly unless the optimizer can transform them into an equivalent join or apply other optimizations.

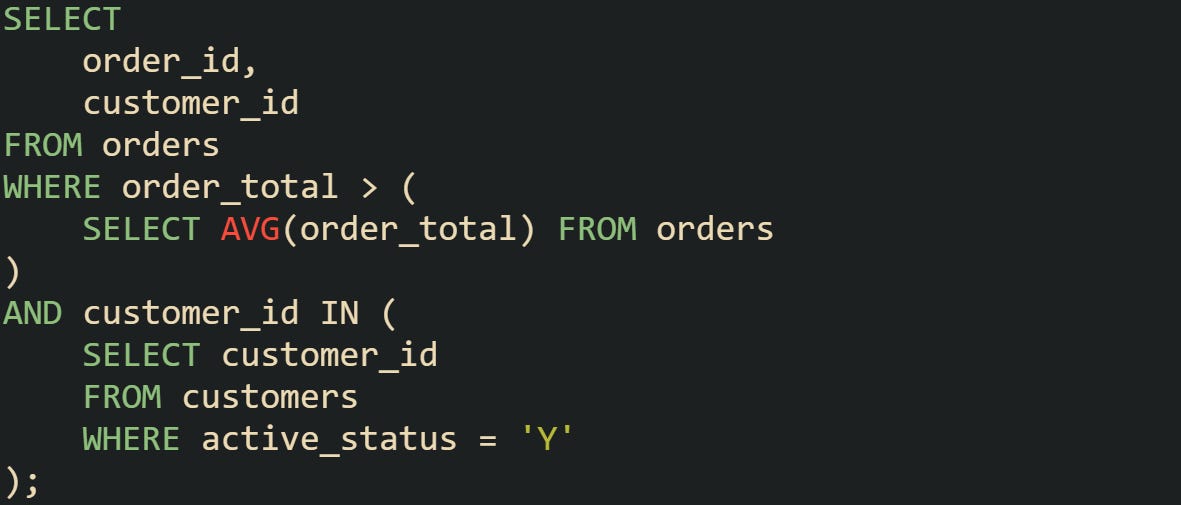

Here’s an example with two uncorrelated subqueries:

Average order total in the subquery is uncorrelated and is computed a single time for the statement and reused during filtering. The IN subquery is also uncorrelated, and query planners typically turn it into a semi-join rather than materializing a literal list. This difference in correlation directly affects performance, and most database engines take advantage of it when planning execution.

Combining Subqueries with FROM and Complex Conditions

Subqueries don’t have to live only in SELECT or WHERE. When placed in the FROM clause, they act like temporary result sets that the outer query can treat as if they were regular tables. This makes it possible to pre-aggregate or filter data before the main part of the query runs. Combining that with conditions in WHERE lets you build statements that answer very specific questions in one pass, without creating intermediate tables in the database.

Working with Subqueries in FROM

A subquery in FROM is a derived table. The optimizer treats it as a logical table and may either materialize it or fold its logic into the outer plan. It isn’t guaranteed to run first or to be stored as a temporary table. This is useful for precomputing aggregated values or reducing large datasets before further filtering.

Consider finding the highest selling product per category. The subquery groups the data and calculates totals, and the outer query decides which rows to keep.

You can also chain multiple derived tables together. For instance, one subquery can calculate monthly totals, while another filters for months over a sales threshold. Each acts as a building block the outer query can stack into the final result set.

Filtering Based on Another Table

Sometimes the goal is to return rows from one table only if related values exist or don’t exist in another table. While joins can work for this, a subquery in WHERE can be a clearer way to express that the second table is purely for filtering purposes.

To list products that have never been ordered:

What's happening is the subquery gathers all product IDs found in order_details. The outer query then returns only those products whose IDs aren’t in that list. This avoids extra join logic when you just need a presence or absence check.

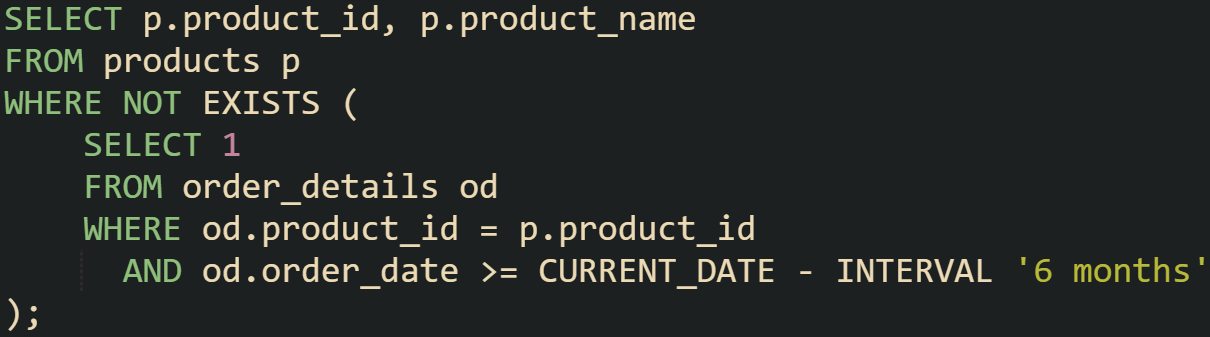

You can also apply more complex filtering with conditions inside the subquery. If you wanted products not ordered in the last six months:

Results are trimmed to only recent orders before being passed to the outer query, allowing it to avoid scanning records that aren’t needed.

Comparing Against Aggregate Results

A common use for subqueries is comparing each row against a calculated aggregate. This works well for both correlated and uncorrelated forms, depending on whether the calculation changes per row or stays constant for the whole query.

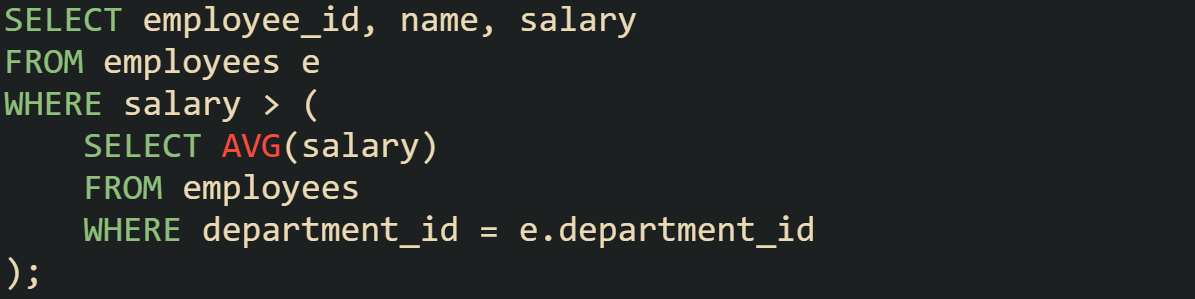

To get employees earning more than their department average:

Here, the correlated subquery relies on department_id from the outer query to determine its result. It calculates an average for that department, and the outer query keeps only those above it.

For a case that doesn’t depend on the outer row, you might compare against a global maximum:

Maximum order value is computed once, then applied to match rows. If there’s a tie for the largest order, all matching rows are returned without recalculating the aggregate for each match.

Conclusion

Subqueries work by allowing one query to supply results that another query can act on, all within the same statement. Their mechanics depend on where they’re placed and whether they depend on values from the outer query. When uncorrelated, they can be run once and reused, reducing repeated computation. When correlated, they’re evaluated for each outer row, which means the database may run them multiple times or rewrite them into joins to improve efficiency. Placing them in SELECT, WHERE, or FROM changes how they interact with the rest of the statement, but in every case, they let you build results from multiple logical steps without creating temporary tables or running separate queries.