Starting a Spring Boot application involves much more than only calling SpringApplication.run. After everything loads, there’s usually a short window before it starts serving traffic where you can get things ready. That moment is perfect for running quick prep work like priming caches, preloading dependencies, or opening connection pools so the system responds smoothly once requests start flowing. It’s a small investment that helps your service start faster and stay responsive right from the first request.

Basics of Spring Boot Startup Events

Every Spring Boot application goes through a precise sequence of startup steps before it’s ready to take traffic. That sequence defines when the environment is built, when beans are created, and when the context is fully refreshed. These moments matter because they decide what parts of the application are safe to interact with. When you need to trigger warm-up work like caching or data preloading, timing becomes everything.

The Event Sequence During Startup

Spring Boot publishes a series of lifecycle events that developers can listen to as the application starts. Each one signals that a certain phase of startup has been reached. The order generally looks like this:

ApplicationStartingEventhappens first, before the context or environment is created. This is where you could log very early startup details or tweak properties before anything else runs.ApplicationEnvironmentPreparedEventcomes next, fired once the environment is ready but before the context exists. It’s a window where you can read or adjust environment variables and property sources.ApplicationPreparedEventruns when the context has been created and bean definitions are loaded but not yet refreshed.ApplicationStartedEventhappens after the context is refreshed but before any command line runners execute.ApplicationReadyEventsignals that everything is ready, runners have completed, and the application can handle requests.

There are also AvailabilityChangeEvent notifications that update readiness and liveness state, which are especially helpful in cloud platforms where probes depend on those signals.

A quick way to inspect these events is to register an application listener with SpringApplication so it receives early events before the context exists:

This prints the full sequence, including early phases like ApplicationStartingEvent and ApplicationEnvironmentPreparedEvent, which a bean listener inside the context would miss.

Why Startup Events Matter For Warm Up Tasks

When an application starts, many background components initialize at different times. Data sources, message brokers, and caches might all come online in their own order. Launching warm-up work too early risks hitting beans that aren’t ready yet. Launching it too late could delay your readiness checks. Startup events bridge that timing gap by giving you an entry point that fires exactly when certain conditions are met.

A good example is ApplicationReadyEvent, which guarantees that all beans are available and the application context is fully refreshed. Code listening to this event can safely call other services or start background jobs without clashing with initialization. For simpler scenarios where all you need is to perform some light configuration right before readiness, ApplicationStartedEvent is often enough.

You can also chain multiple listeners to stage warm-up phases. Imagine running a lightweight health check right after ApplicationStartedEvent, followed by heavier cache priming once the system fires ApplicationReadyEvent.

This works well in applications that depend on external services where startup time matters. The key is matching the right event with the right action, keeping heavier work closer to readiness and lighter setup work earlier.

Choosing The Right Hook For Warm Up Work

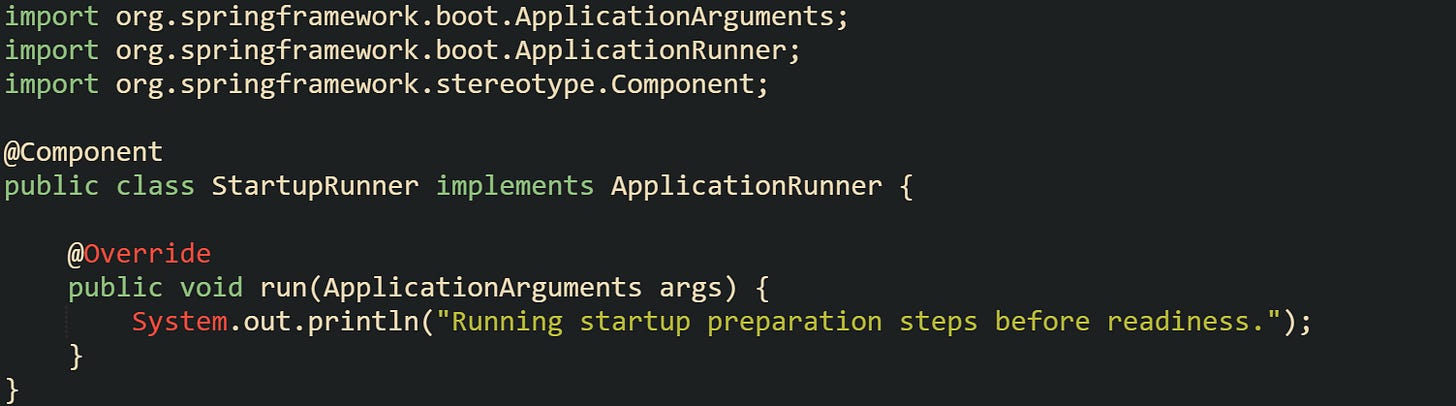

Spring Boot gives several ways to run code automatically during startup, each firing at a slightly different moment. The choice depends on what needs to be ready for your warm-up logic to run safely.

For example, CommandLineRunner and ApplicationRunner interfaces execute immediately after the context is refreshed but before ApplicationReadyEvent is published. This can be helpful for actions that don’t depend on full readiness, like setting up default configurations or verifying file paths.

On the other hand, some warm-up work depends on calling other beans or making network requests. That’s when ApplicationReadyEvent is more appropriate because it fires after all runners have completed and the application is fully initialized.

Another choice is listening to specific availability changes. By observing AvailabilityChangeEvent, you can trigger or delay certain warm-up actions based on readiness state. This works in core Spring Boot; add Actuator only if you want health endpoints for probes.

Selecting the right hook isn’t about adding more code but about matching your work with the correct lifecycle moment. Doing so keeps startup predictable and avoids conflicts between early initialization and application logic that depends on fully constructed beans.

Implementing Warm Up Tasks After Startup

Spring Boot gives developers several points in the startup process where they can safely run custom logic, but warm-up work belongs at the tail end of that process. The goal is to have your services, caches, or external connections ready before the application begins handling real requests. That usually means tying your logic to startup events that fire after the application context is refreshed and all beans are available.

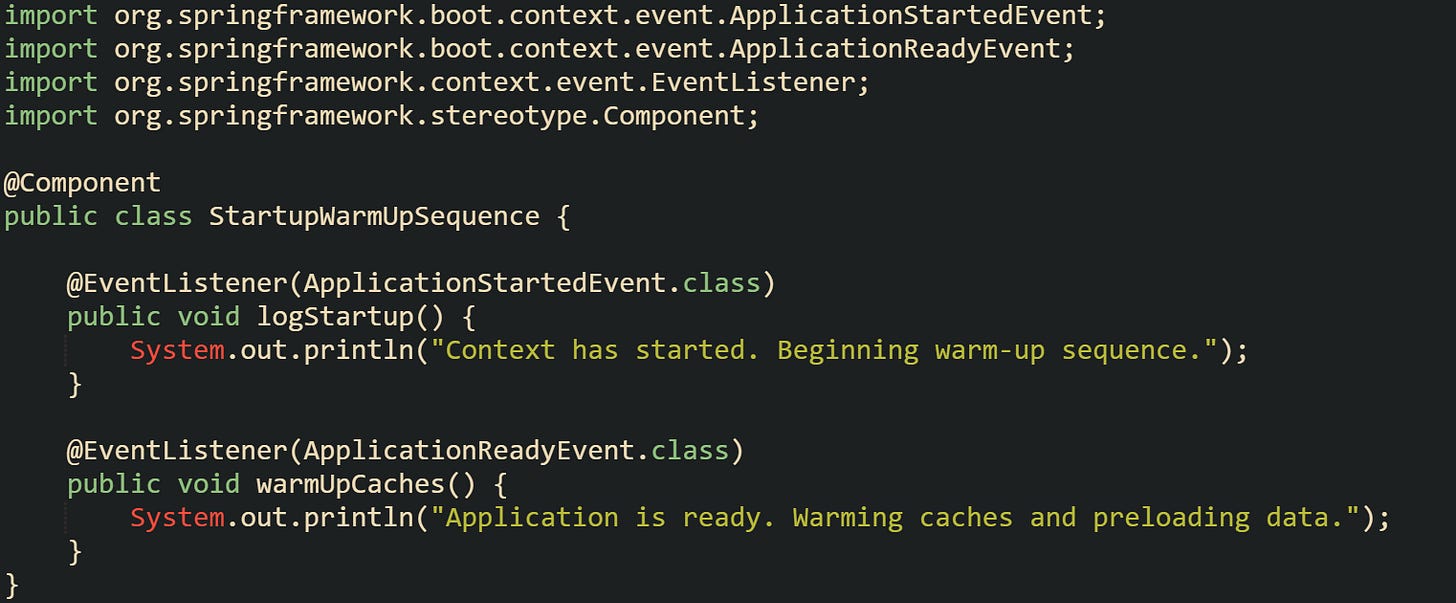

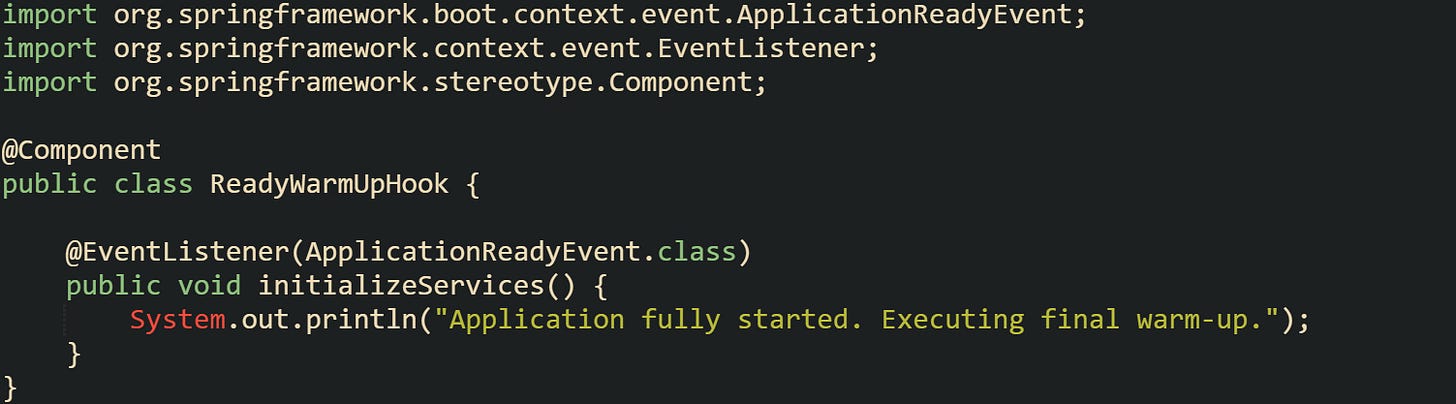

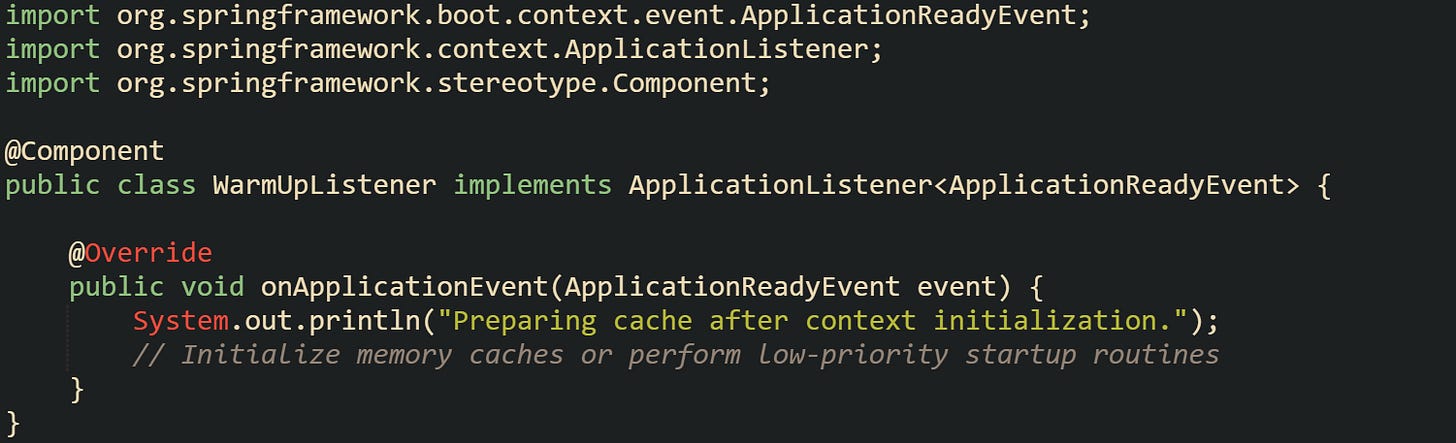

Defining a Listener for ApplicationReadyEvent

The ApplicationReadyEvent fires at the very end of startup, right after any CommandLineRunner or ApplicationRunner beans finish running. It’s a dependable point to begin warm-up work because every part of the context has been loaded, all dependencies are wired, and the application can safely interact with databases, caches, or network services.

A common method is to register a listener using the @EventListener annotation. This keeps your warm-up code neatly separated from the rest of your beans without cluttering main or runner logic.

That code logs a message and could easily be extended to run a quick query to prime the data layer or initialize a connection pool. It runs only once and doesn’t block startup beyond what’s already finished.

If you prefer more structure or need multiple warm-up stages, you can use the ApplicationListener interface to manage them separately.

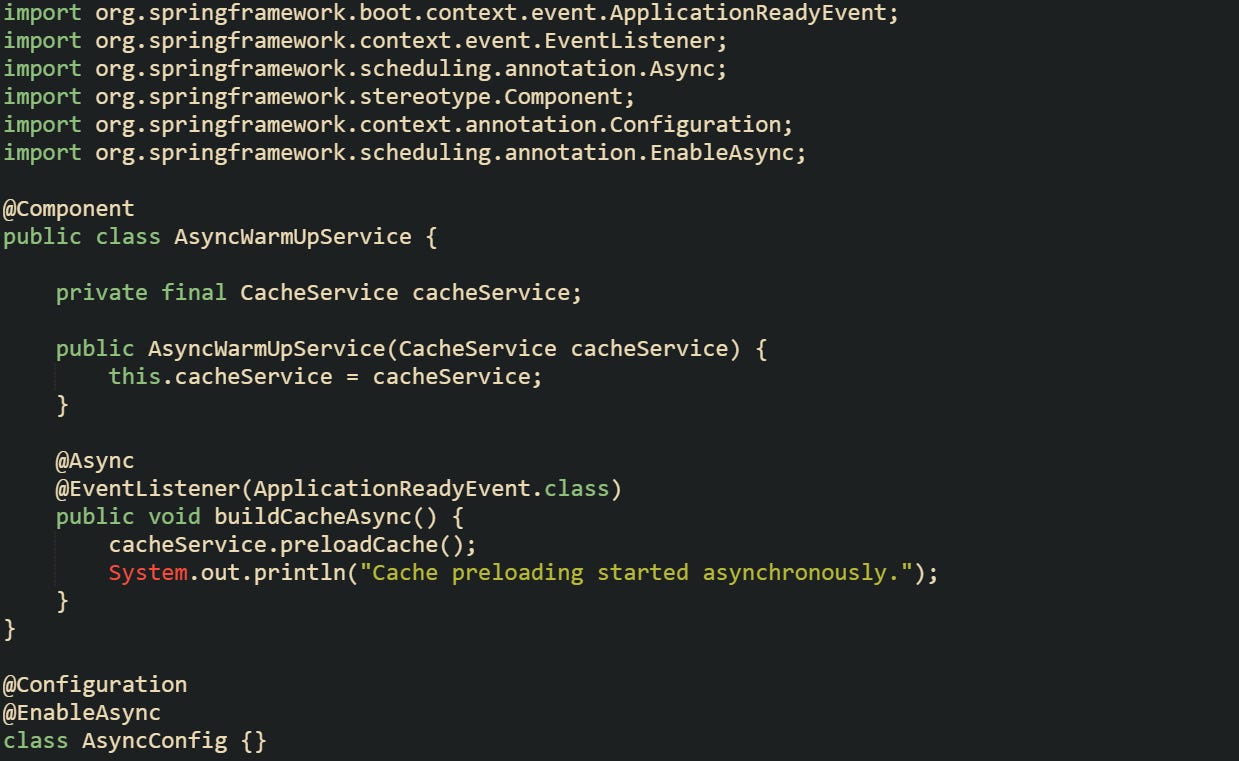

Some teams also prefer triggering asynchronous logic from within the listener. That keeps startup quick while still allowing heavier warm-up processes to run in the background. This can be done by injecting a TaskExecutor and offloading work to a new thread, preventing slow initialization from delaying the readiness state.

Typical Warm Up Tasks You Might Run

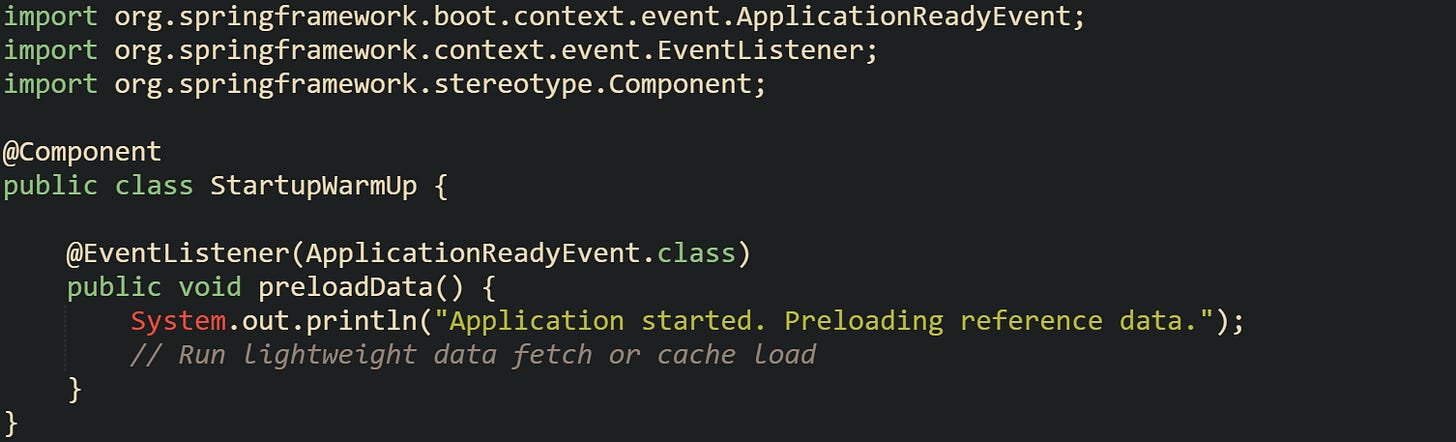

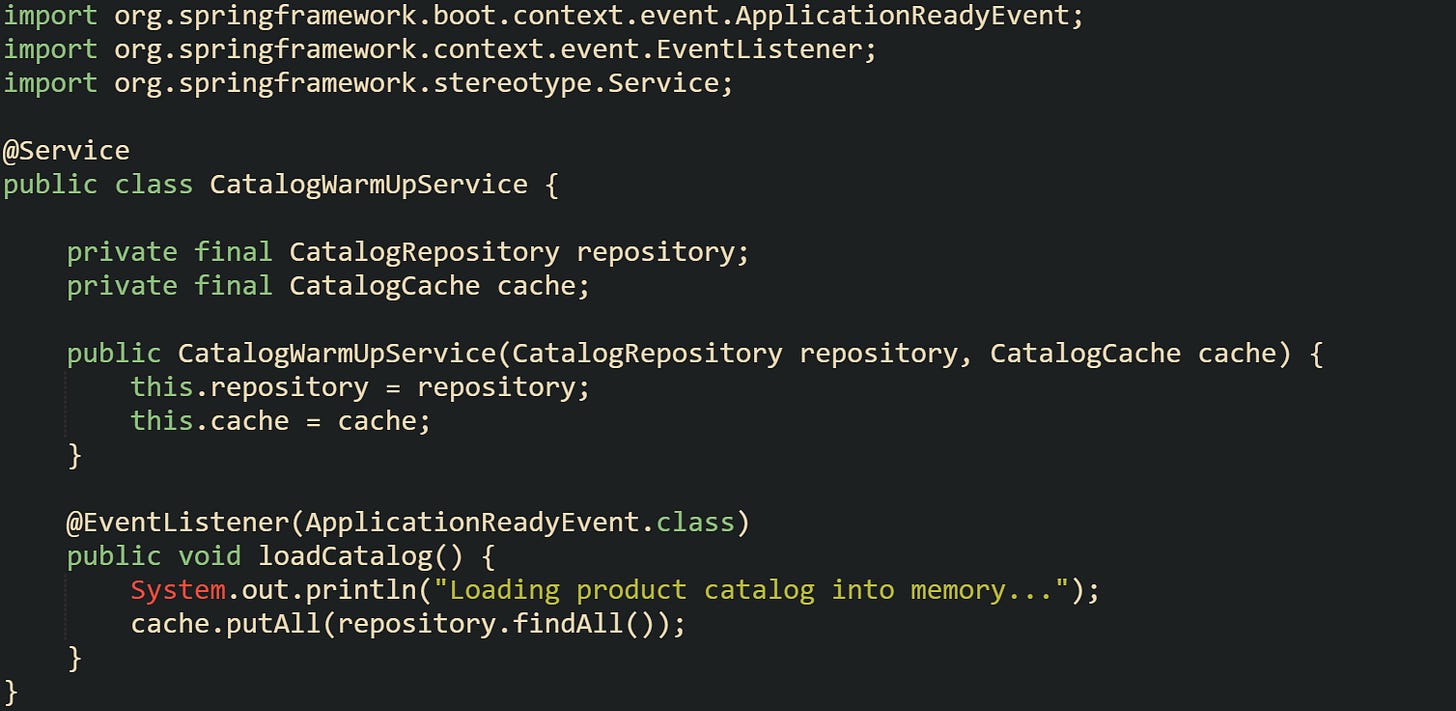

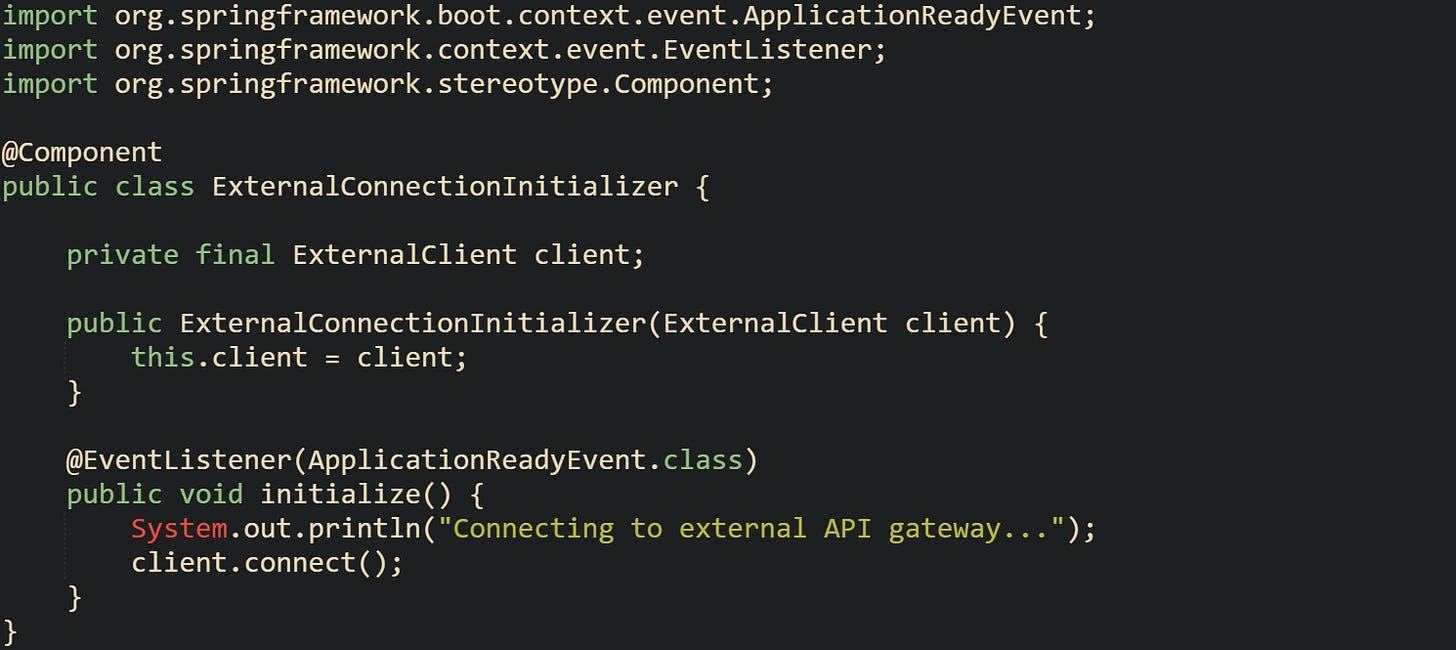

Warm-up work varies depending on what the application does, but the general goal stays the same: get data, connections, or caches into a ready state before handling requests.

A common task involves populating in-memory caches. Doing so early removes latency spikes that appear when the first real user hits an endpoint. Suppose you’re running a service that depends on a large catalog stored in a database. You can load it into memory once and reuse it during runtime.

A different frequent case involves pre-establishing external connections, such as initializing a message broker or authenticating with a third-party API. That reduces connection lag when actual requests arrive.

Some developers also trigger warm-up logic to compile expression templates, pre-validate configuration data, or generate static reports that users often request first. What matters is that these actions reduce the workload at runtime and help maintain consistent performance right after startup.

Avoiding Blocking Readiness or Health Checks

While it’s tempting to run every warm-up process immediately after startup, doing too much work too early can cause your readiness probes to fail. When a container platform like Kubernetes expects a fast readiness response but your warm-up logic is still running, it might mark the instance as unhealthy and restart it unnecessarily. The easiest way to avoid this issue is to run heavy warm-up processes asynchronously. You can combine the @EventListener annotation with @Async to offload the work without blocking the main thread. This method needs a configured executor bean, usually ThreadPoolTaskExecutor, to manage background threads safely.

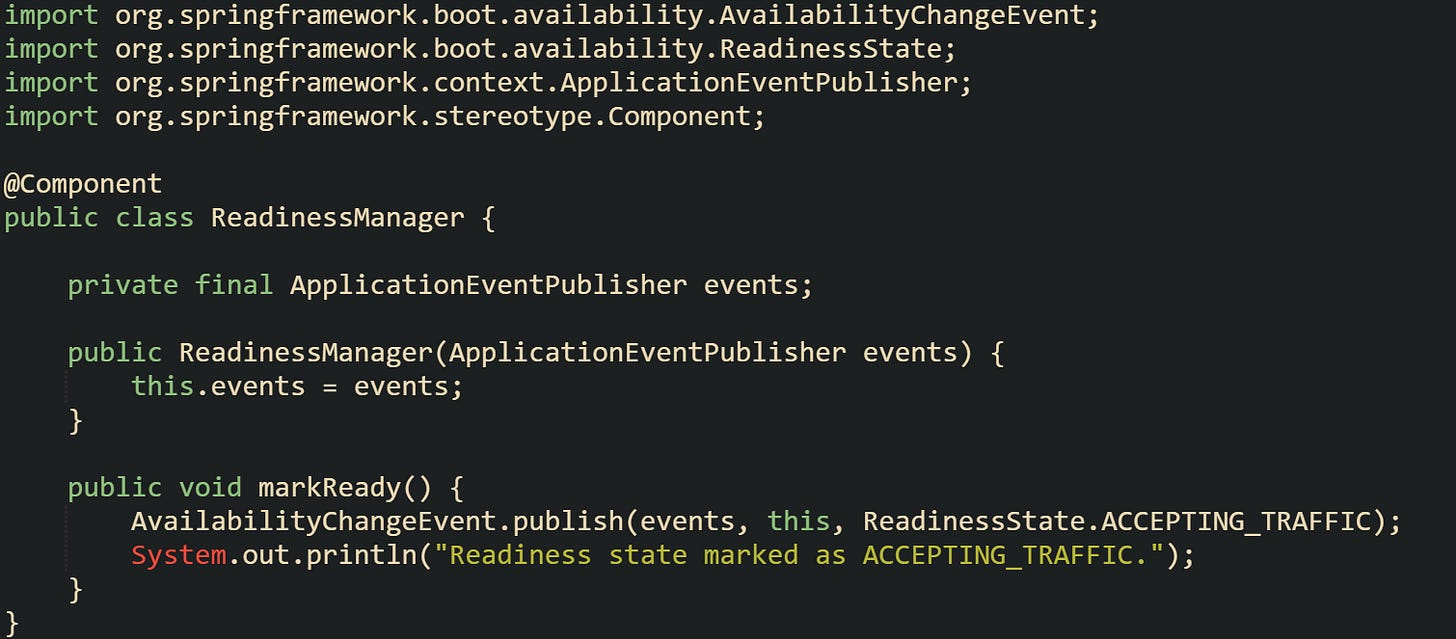

Also, a good practice is marking readiness manually only after warm-up finishes. Publish an AvailabilityChangeEvent to set the readiness state after your background work completes, which lets orchestration systems see that the application is ready for traffic.

Balancing startup readiness and warm-up depth is part of what makes these event listeners valuable. You can prepare your application without delaying service registration or health responses, keeping both startup speed and stability in line.

Warm Up Scenario Example

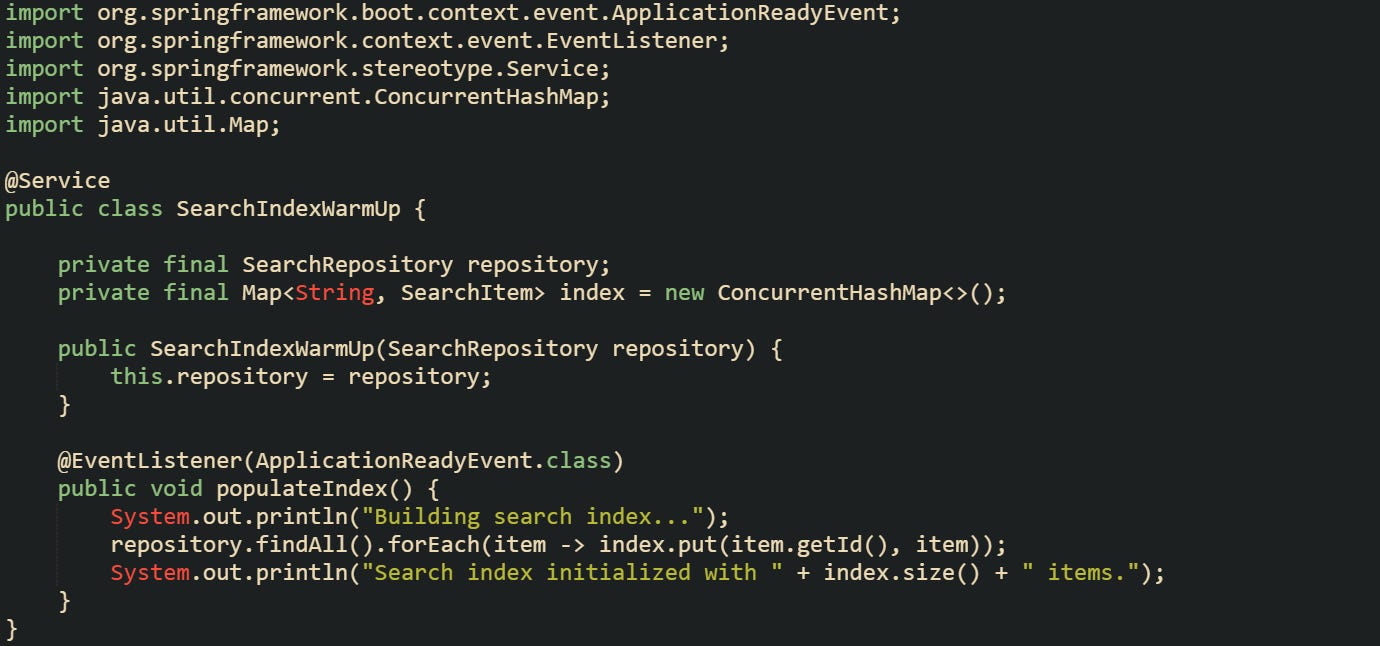

I’m personally a visual learner, so lets imagine we are working with an application that provides search results for a large dataset. The search relies on an internal cache that must be filled from a data source before queries run efficiently. Loading it during normal traffic would slow down the first few users, so it’s smarter to populate it right after startup.

A service like that benefits from having the index ready before traffic hits. The cache stays warm, queries respond fast, and subsequent updates can happen in the background without holding up startup.

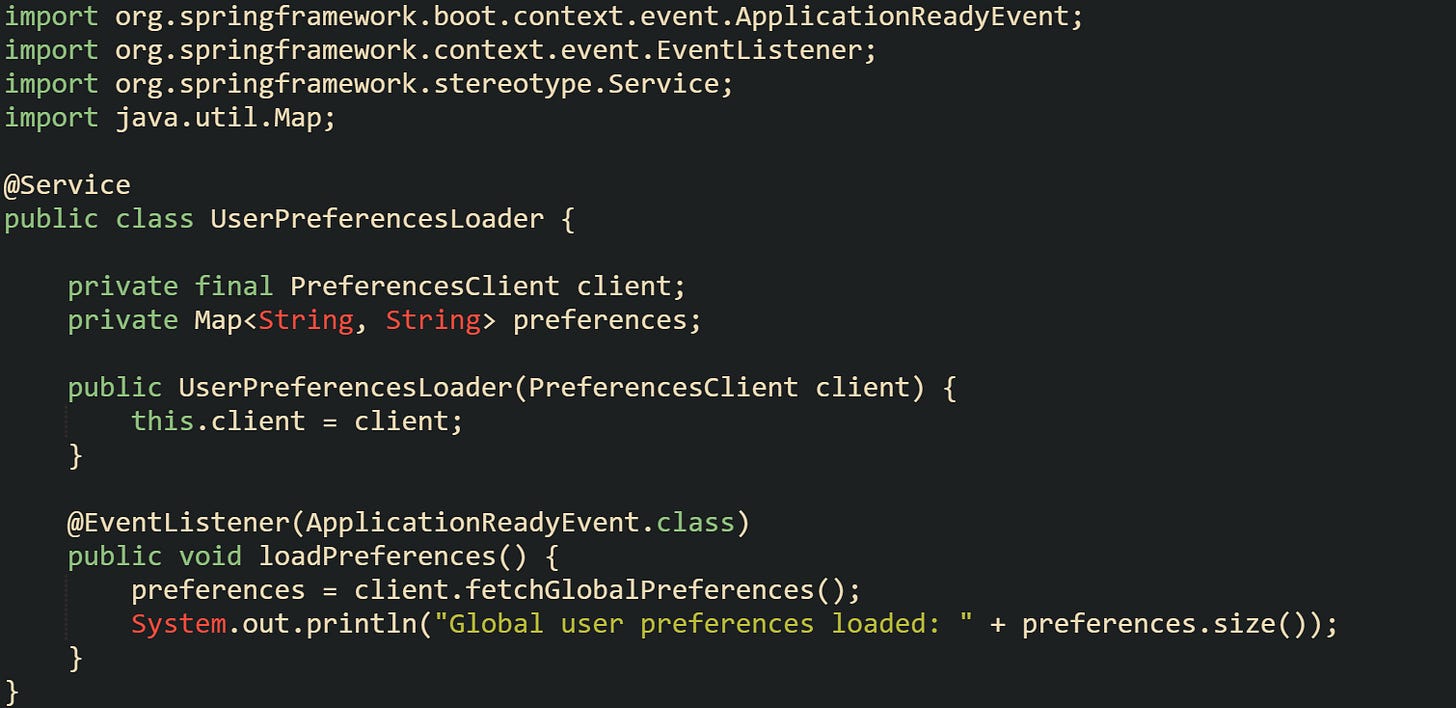

Another situation could involve preloading user settings into memory from a distributed configuration store. It’s a lightweight process but helps prevent extra requests at runtime.

Both cases rely on the same event mechanism but tailor the warm-up process to the system’s needs. The cache load is heavy and benefits from asynchronous execution or batching, while preference loading can be synchronous because it’s small and quick. Each of these examples builds on the same principle, prepare what your service depends on right after startup so that traffic experiences minimal delay from the first request onward.

Conclusion

Spring Boot startup events give developers a natural way to time their warm-up work without interfering with initialization. Each event reflects a different stage of readiness, which makes it easier to match preparation steps to the moment the application is stable. Running code at ApplicationReadyEvent or scheduling background work through asynchronous listeners keeps startup smooth while giving your services, caches, and connections a head start. When these pieces line up properly, the application feels responsive from the very first request.

![import org.springframework.boot.SpringApplication; import org.springframework.boot.autoconfigure.SpringBootApplication; import org.springframework.context.ApplicationListener; import org.springframework.context.ApplicationEvent; @SpringBootApplication public class DemoApplication { public static void main(String[] args) { SpringApplication app = new SpringApplication(DemoApplication.class); app.addListeners((ApplicationListener<ApplicationEvent>) event -> System.out.println("Event triggered: " + event.getClass().getSimpleName())); app.run(args); } } import org.springframework.boot.SpringApplication; import org.springframework.boot.autoconfigure.SpringBootApplication; import org.springframework.context.ApplicationListener; import org.springframework.context.ApplicationEvent; @SpringBootApplication public class DemoApplication { public static void main(String[] args) { SpringApplication app = new SpringApplication(DemoApplication.class); app.addListeners((ApplicationListener<ApplicationEvent>) event -> System.out.println("Event triggered: " + event.getClass().getSimpleName())); app.run(args); } }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!-2Ui!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F31f69366-9e74-4143-ace0-f5b862588bf0_1519x522.png)